An artist studio by Club Triangle

By Katharine James

September 12, 2024

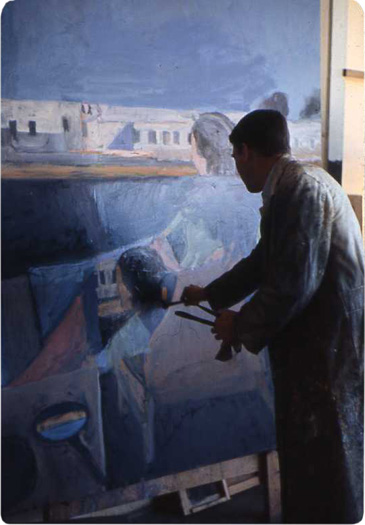

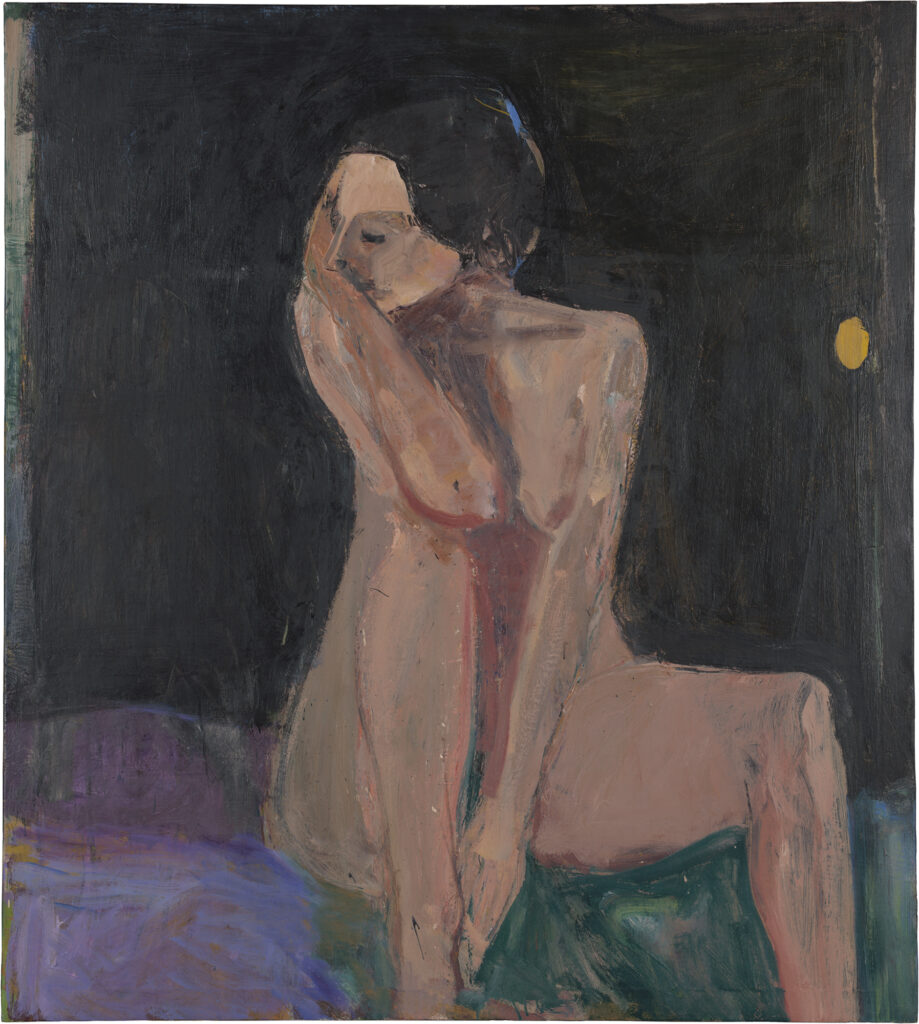

The year 1958 was significant for Richard Diebenkorn as he continued to develop into a mature artist, slowly gaining recognition for his unique application of abstract expressionist brushstrokes to figurative compositions. Before turning his attention to painting women, men, interiors, still lifes, and landscapes in the mid 1950s, he made large abstract paintings with an explosive and centrifugal quality. They often were arranged loosely in a tripartite banding pattern, and the artist liked to pack them with color. “It wasn’t fun unless all the colors, all the characters, were present,” he said of his numbered Berkeley paintings, which immediately predate his turn to figuration. He included “every hue and every variation into the picture. With six basic hues, and at least one variant for each—that’s twelve—plus black and white and grays, I would get the ball rolling.”1 While his new body of work was quieter, more introspective, and often saturated with a specific mood or feeling, the artist continued to use some of the qualities mastered in his previous abstract series. His color stayed the same. His varied brushstrokes appear from solid strips to energetic stretching marks to wiry thin lines. He placed blues next to reds, pinks, and tans and milky yellows alongside purples and greens.

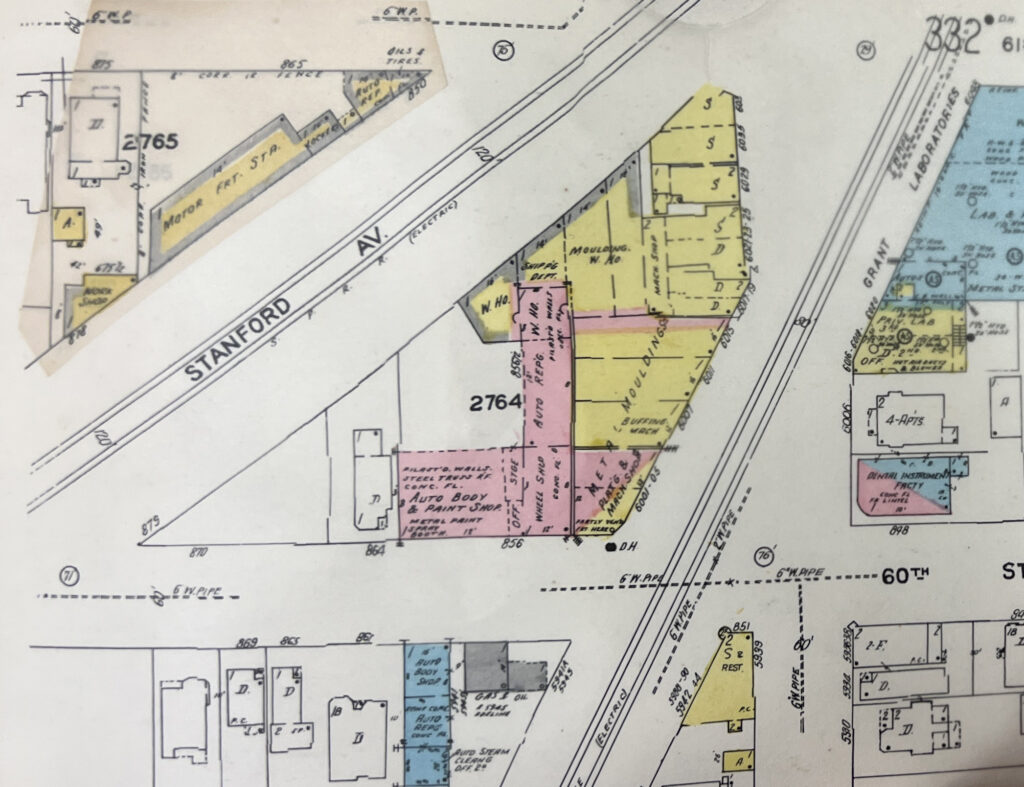

Diebenkorn had been painting in a representational mode for about three years when he decided to rent a new studio along the Berkeley-Oakland border in 1958. The space was located at the convergence between Stanford Avenue and Adeline and 61st Streets. The lot and building were triangular, and his studio, roughly triangular as well, was on the ground floor also occupied by a local bar frequented by commuters returning from jobs in San Francisco.2 He had had recent success with a solo exhibition in New York where his dealer, Elinor Poindexter, had sold twenty-six figurative paintings in the first three days of the show,3 giving him the financial freedom to focus exclusively on his painting for a period. “I’m stunned by the number of purchases,” the artist wrote. “I’m refraining from any interpretation of this phenomenon. I hope that most of them are definite since I felt, on receiving the news, morally obliged to withdraw my Guggenheim application—which I did. I have no more work to send back to you….My studio becomes a pretty uncomfortable place when it is cleaned out and although I continue to scrape and repaint day by day I’m not coming thru with anything that is what I want.”4 He temporarily quit his day job at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, taking a year off from teaching, and found working solely in his studio (built by him in the backyard of his home on Hillcrest Road in Berkeley) restless and less stimulating. “There was never any reason to leave the premises, you know, and this became suddenly lonely not teaching—or not doing something, not having some reason to go to San Francisco, or go anywhere,” said Diebenkorn. And I could just remember one morning looking out the window and watching these men on their way to the bus with their newspapers under their arms and envying them.”5

It has long been thought that Richard Diebenkorn worked in his Triangle Building studio from 1958 to 1965, taking an academic-year away during an artist residency at Stanford University in 1963–64 and traveling to the USSR in the Fall 1964. He returned in 1965 at which time he was told the building was condemned to make way for the construction of the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART),6 so he went back to painting in his studio behind the Hillcrest Road house. History is porous and much of it is forgotten, often eroded by ambiguity, missing data, notes unreadable or smudged, and gaps in memory. Today, in the latest installment of the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation digital series, From the Basement, another piece of information previously lost to time slots into the collective memory bank: Richard Diebenkorn’s studio along the Berkeley-Oakland border, where a bar called Club Triangle operated, was not demolished in 1965.

The previous year, in 1964, Richard Diebenkorn lived at Stanford University after he was appointed their first artist-in-residence with the support of his undergraduate professor Daniel Mendelowitz.7 He moved to campus for the academic year (1963–64) with his wife Phyllis and son Christopher. His daughter, Gretchen, also happened to be entering her freshman year at the university in Fall 1963. The residency did not require the artist to teach a class on campus, but Diebenkorn opened his studio weekly to students who wanted to stop by and visit. He also stayed active in weekly drawing sessions—a practice begun in the mid 1950s when he was on the precipice of his transition from abstraction to figuration—with fellow artists Elmer Bischoff and Frank Lobdell in San Francisco. His life shifted for a short time away from the normal routine established in Berkeley, going to and from his Triangle Building studio, and the state of this studio is unknown during his time away.8

For many years, especially during the intensive research phase of Richard Diebenkorn: The Catalogue Raisonné (Yale University Press, 2016), Foundation staff on occasion mused about whether the Triangle Building survived. It nagged Daisy Murray Holman, the former Head of Archives at the Foundation and author of the Chronology in the artist’s catalogue raisonné of unique works. She lived nearby, often walked her dog on the diagonal blocks in the area, and ate with her family at Lois the Pie Queen, a 50-year family-owned restaurant located at 851 60th Street in a historic building a block away from the old studio space. She kept turning it over in her mind, considering whether the streets were renamed or moved at some point in Oakland’s history. With the Triangle Building being situated along the Oakland-Berkeley border and the development of the BART line in the area,9 it seemed possible.

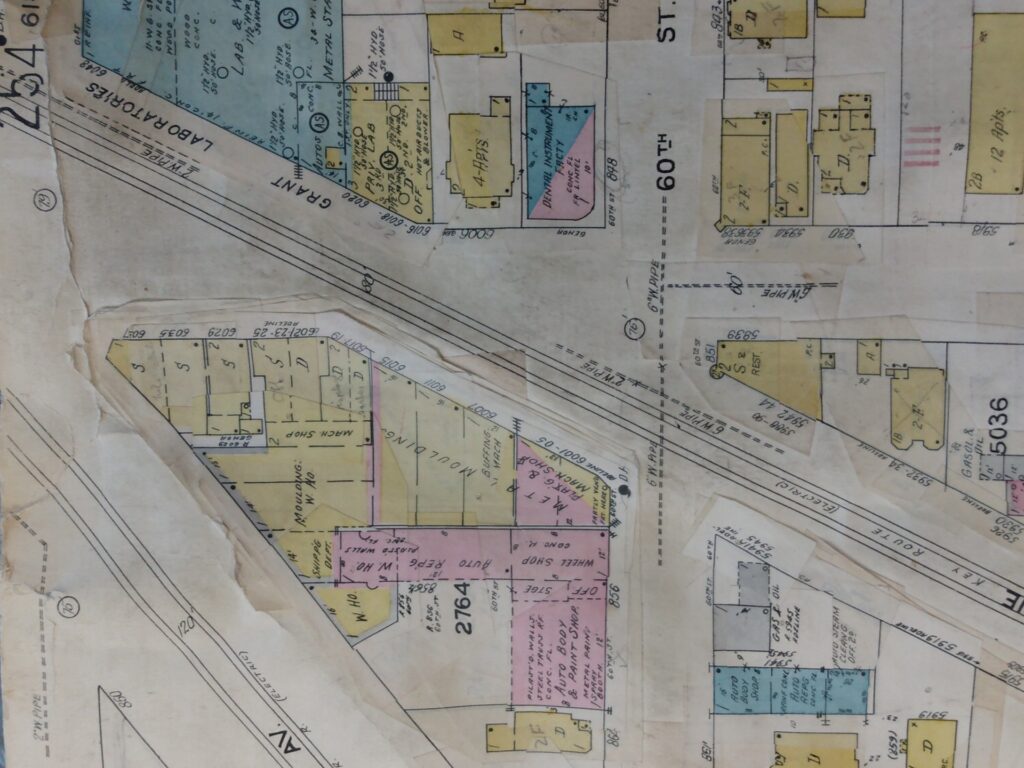

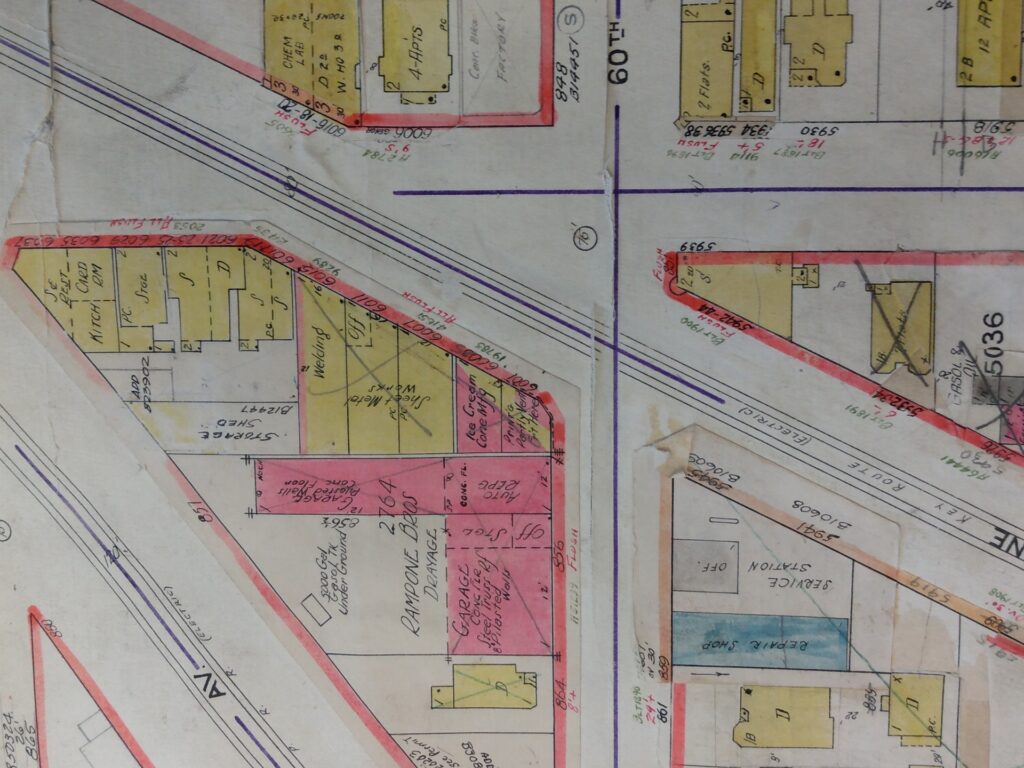

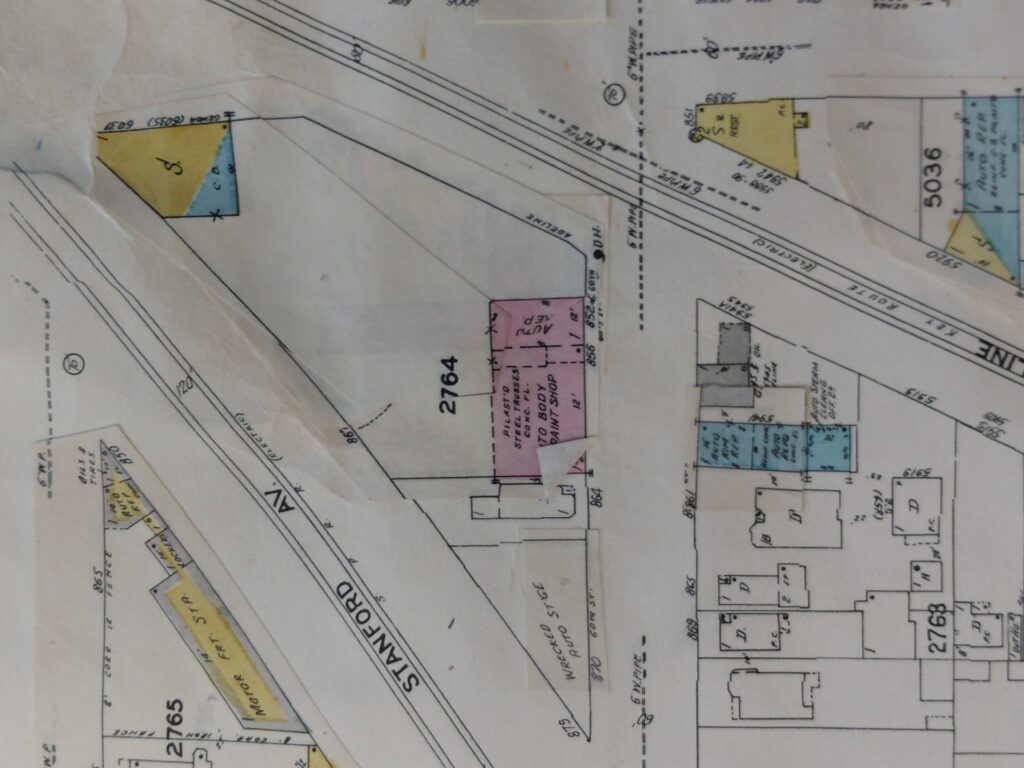

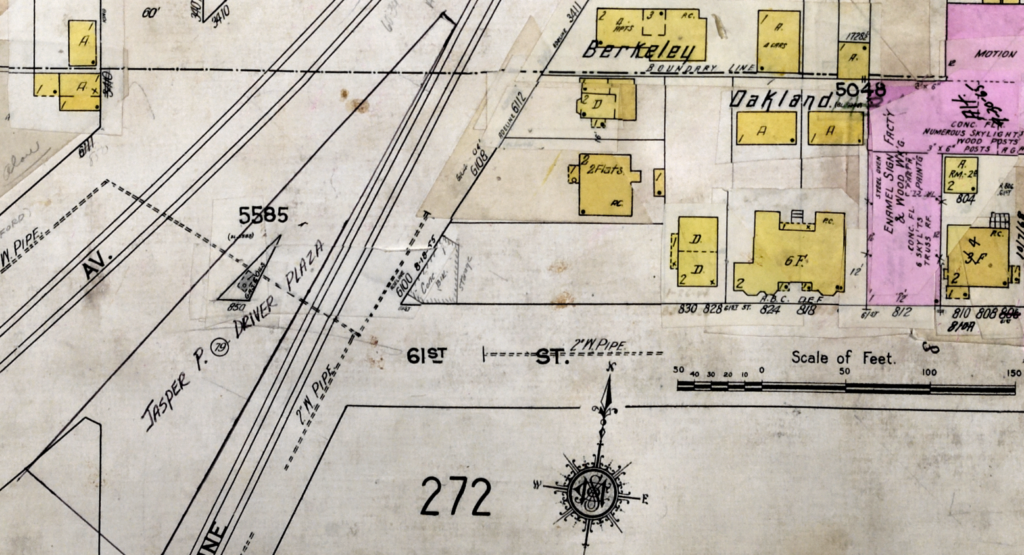

Joined by Jacquelyn Northcutt, Digital and Publications Research Assistant at the Foundation, we set out for the Oakland History Center at the public library by Lake Merritt. We started with the Sanborn Maps, hand-drawn renderings of every city block from the 20th century, marking storefronts, railways, apartments, and addresses. We learned immediately the streets names remained unchanged and realized quickly the maps omitted any mention of a building or Club Triangle by its address, 851 61st Street (taken from a photograph in the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives), or its business name. We walked down the corridor to scroll through Microfiche and open old telephone books. There, in the 1958 Oakland Telephone Book, was Club Triangle listed at 6031 Adeline. And again in 1965. In 1966 it was missing, instead listed under Klub Triangle at 6031 Adeline. In 1967 and ‘68 it was listed under Klub Triangle & Campus at 6031 Adeline. In 1969 it was missing again as well as in 1970 and ‘71. On day one we had proven the building had survived past 1965.

Telephone Books

| 1953 | Club Triangle |

| 1958 | Club Triangle |

| 1965 | Club Triangle |

| 1966 | Klub Triangle |

| 1967 | Klub Triangle & Campus |

| 1968 | Klub Triangle & Campus |

| 1969 | Not present |

| 1970 | Not present |

| 1971 | Not present |

Reverse Directories

| 1964 | Club Triangle |

| 1965 | Not present |

| 1966 | Klub Triangle |

| 1967 | Klub Triangle & Camp[us] |

| 1969 | Klub Triangle & Campus |

| 1970 | Klub Triangle |

| 1972 | Not present |

We continued to comb through old files, reverse address directories, newspaper clippings, and photographs. In one article, dated to the early 2000s, we read about a walking tour of old bars in the Golden Gate neighborhood of Oakland led by two historians, Donald Hausler and Nancy Smith, from the Oakland Heritage Society. We reached out to them and other members of the local community, then we began building a new timeline. Mr. Hausler started digging into the history of the building from its beginning in the late 1800s and eventually published the article “The Long, Strange Trip of North Oakland’s Club Triangle” in the Journal of the Emeryville Historical Society.10 His research has been invaluable. Mr. Hausler discovered the building in the 1930s was owned by a man named Charles “Charley” Rush who developed the beer garden into a cabaret, adding a liquor store on the premises to make the business legal, which opened in May 1934. “The establishment had several names, including Charley Rush’s Cabaret, Triangle Café, and Triangle Garden.”11 It also had two addresses at this time: 6031–35 Adeline Street and 851 61st Street.

During one visit to the Oakland History Center, Northcutt and I stumbled across an article in the Oakland Tribune, dated September 18, 1967, reporting on a fire that destroyed much of the 6000 Adeline block in the early morning. “An intensely hot four alarm fire destroyed a city block in North Oakland yesterday…by 8 a.m. the triangular shaped block bordered by Adeline, 60th, and 61st Streets and Stanford Avenue was in ruins. A crowd of about 1,000, including several customers who had just left a bar (Klub Triangle) in the block at its 2 a.m. closing hour, gathered to watch the fire. Flames rose 200 feet in the air, and the heat was so intense it was felt two blocks away. Destroyed by the flames was the Klub Triangle, a bar at 6031 Adeline Street, Frank’s Auto Repair, 854-60th Street; the Auto Body Shop, 856-60th St; the Liftruck Service Co. a forklift firm of 867 Stanford Ave, and several vacant buildings between 6015 and 6027 Adeline Street…The fire was not extinguished until 8 a.m.”12 On November 6, 1967, then owner Verlin Mattox filed a building permit with the city to make structural and cosmetic repairs.13 After the 1967 fire, Mattox sold Club Triangle to Bill Burroughs, and “moved around the corner to a new location, 850 Stanford Avenue.”14 On another visit to the Oakland History Center, we uncovered a page in the Oakland Post, dated Thursday, March 27, 1969, featuring Johnny Cruickshank, Sr., bartending at Klub Triangle located at 61st and Adeline in Oakland. On December 15, 1969, the Berkeley Gazette announced an event at the club: “Night club owner Bill Burroughs, proprietor of Mr. B’s Triangle club, is sponsoring a benefit feature live entertainment and dancing. Dancing and a live band will be featured 9 p.m. to 2 a.m. at Mr. B’s Stanford and Adeline Aves.”15 Stanford Avenue and Adeline and 61st Streets all converge in the same triangular block.

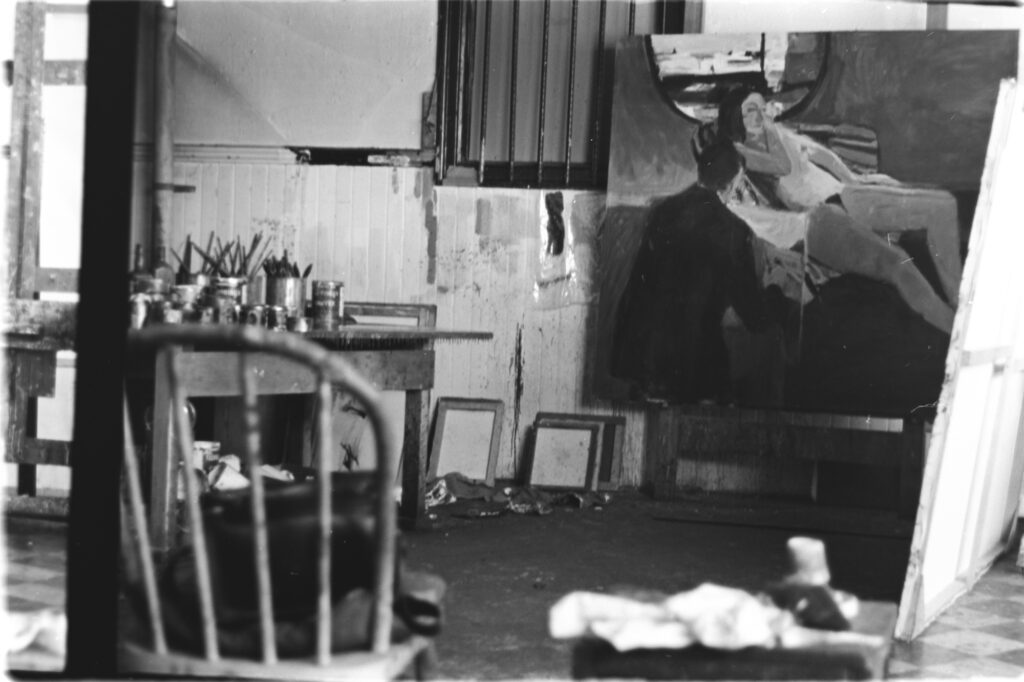

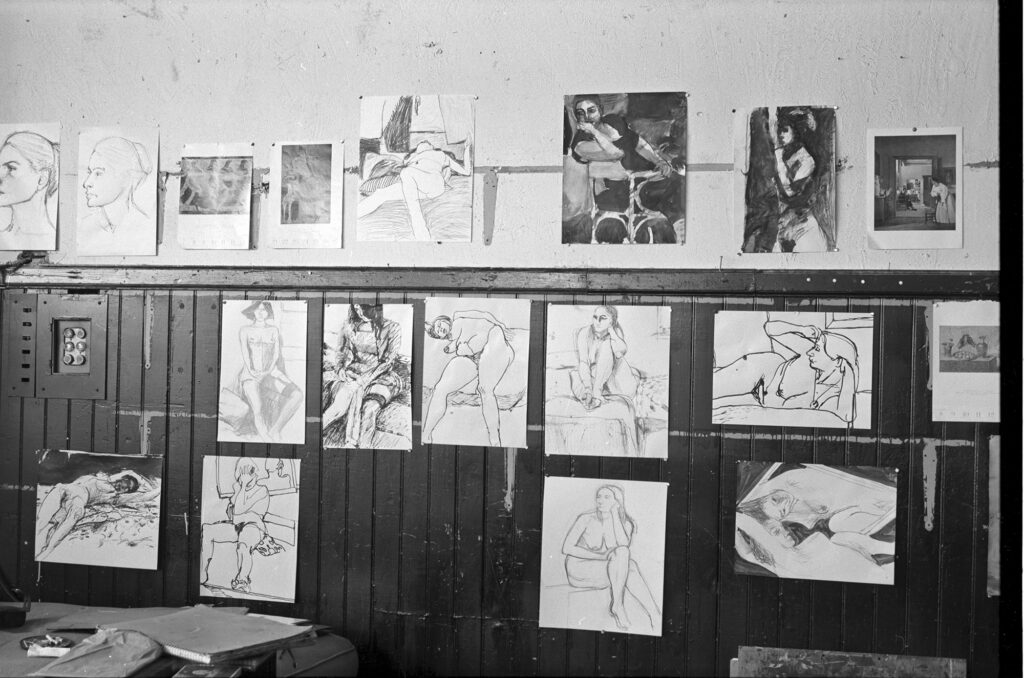

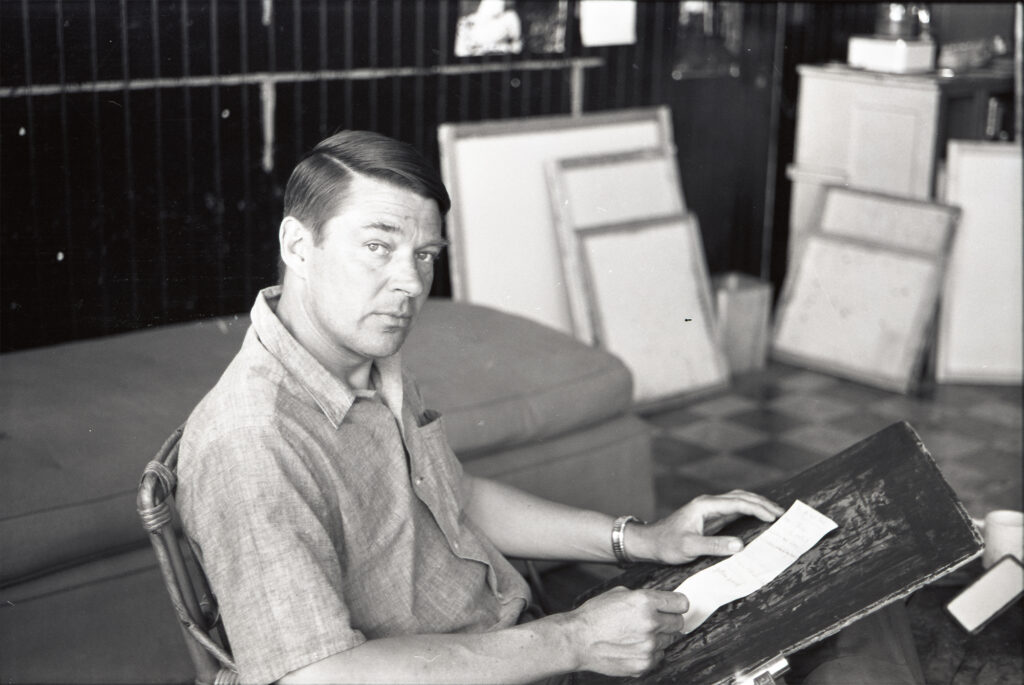

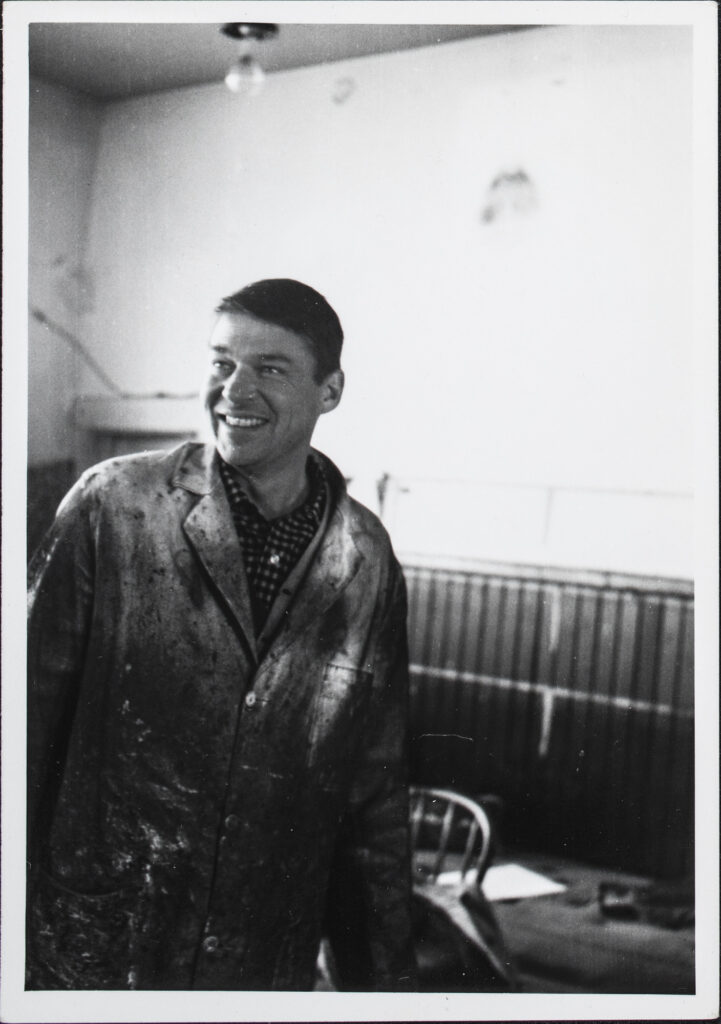

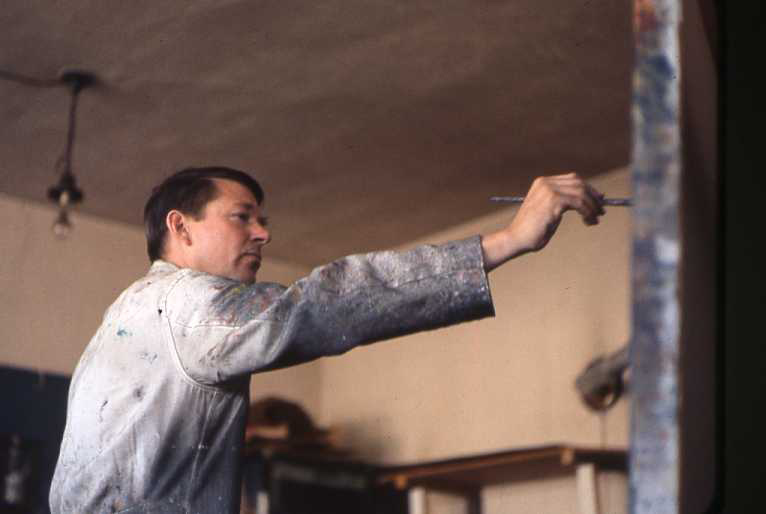

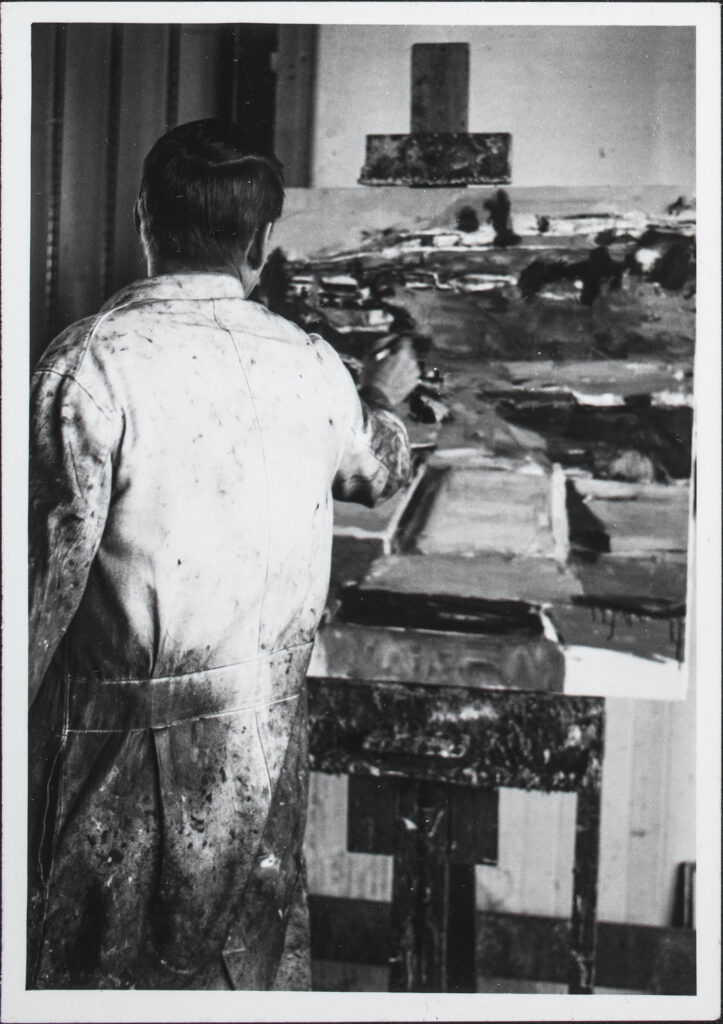

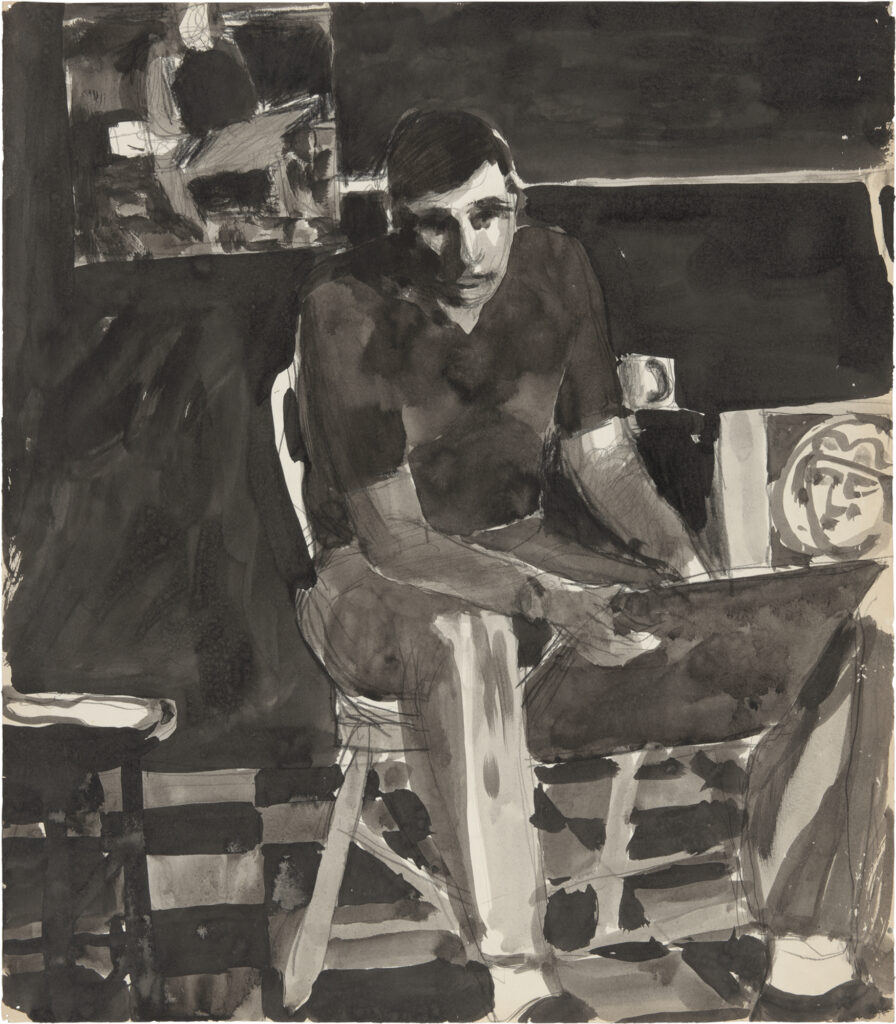

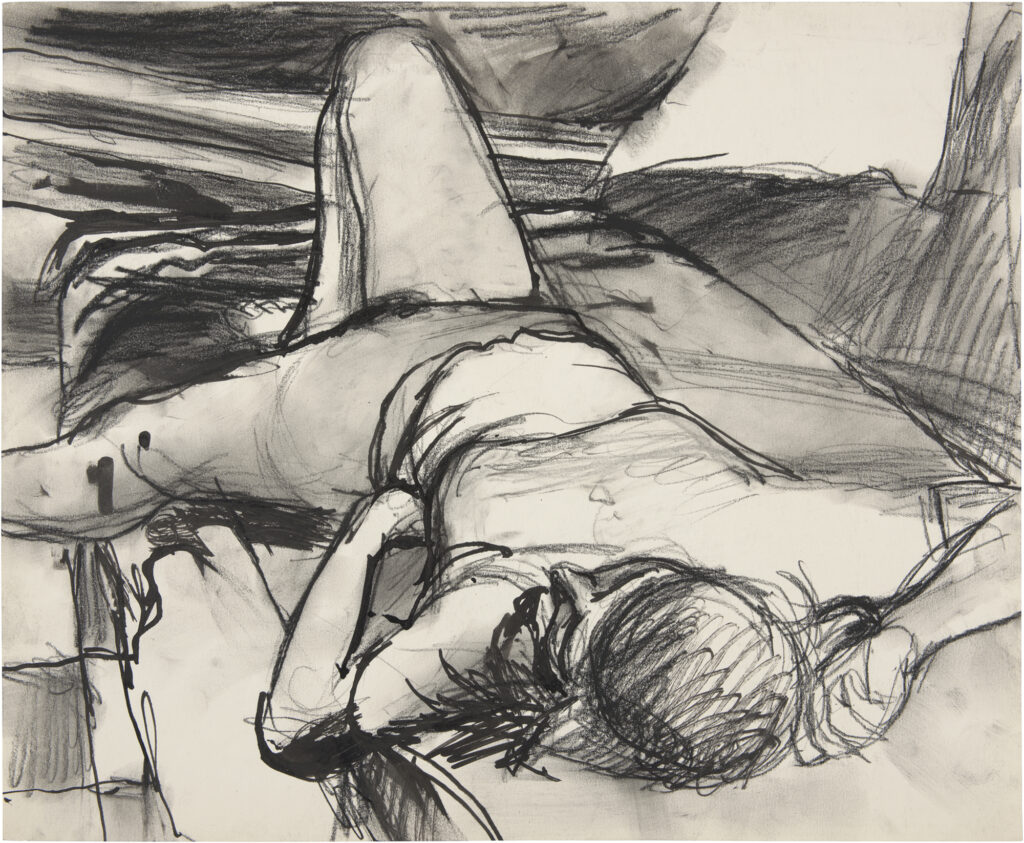

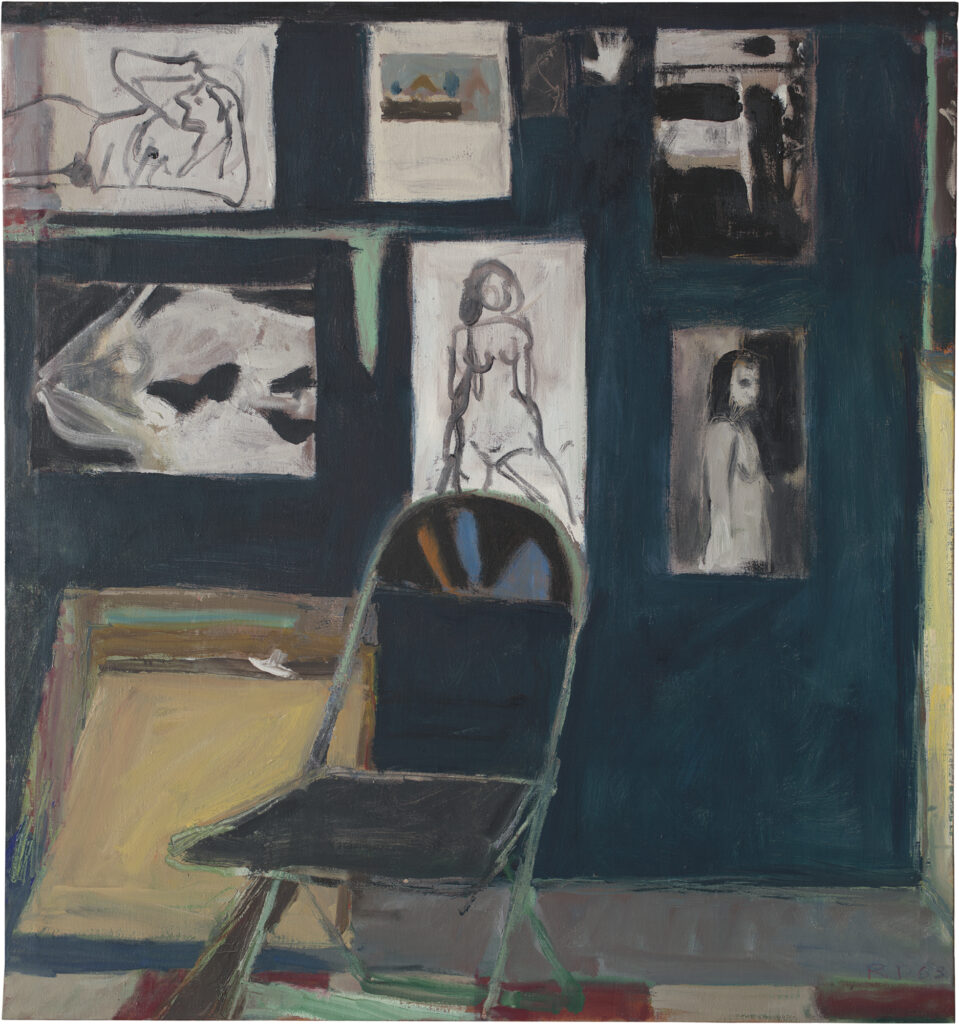

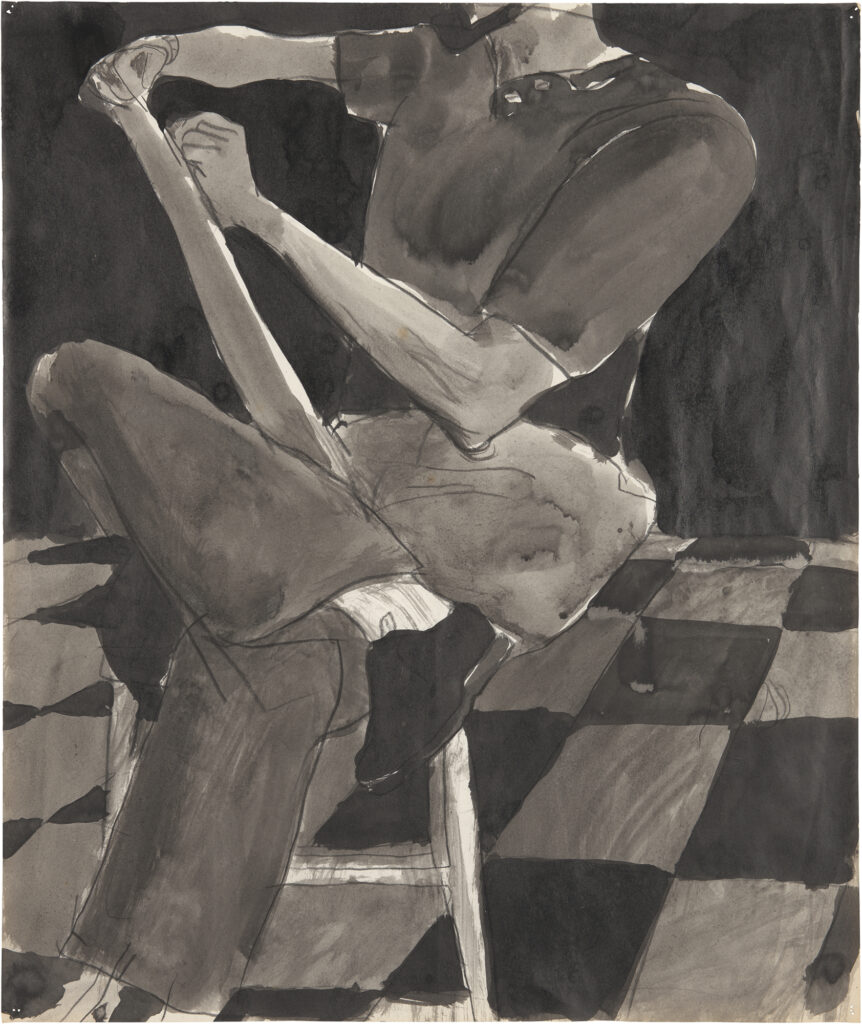

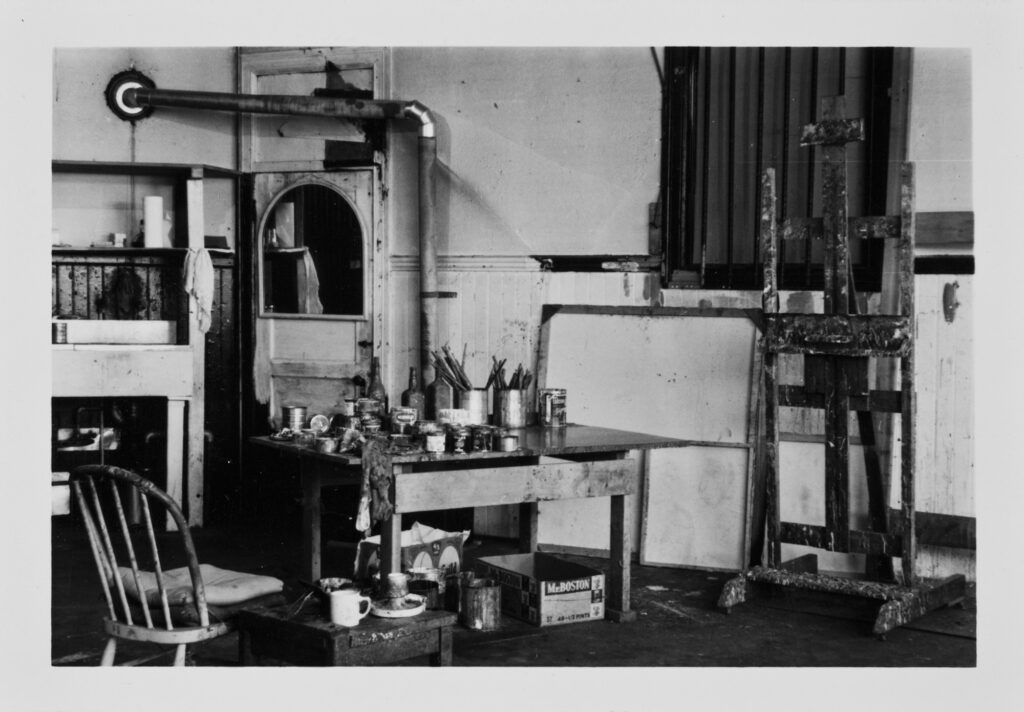

From 1958 to 1965 Richard Diebenkorn painted in the Triangle Building studio. The space had its own address, unlisted as discovered, on the corner of the converging streets. Number 851-61st ran above the door. Upside-down triangles with black clubs ran along the roof line on either end of the building sides. Paned windows partially covered at the bottom provided light and privacy. Red and white checkers covered the floor. Black beadboard wainscotting ran along the edges of the wall. He kept several different types of chairs, a table or two for paints and brushes, metal clip-on lights, an easel, and a daybed in the corner. Stretched canvases leaned against the wall. Drawings finished and in-progress pinned to other walls. The space was dirty by choice. It was worn-in. Silhouettes of old bookshelves or furniture adhered to the walls floated, untethered.16 The artist spent his days here. Seven days a week. Close to three hundred-and-sixty-five a year. He made large paintings of interiors, walled courtyards, urban hillsides, streets, women alone, men alone, the two sometimes together. He drew hired models nude on the daybed with the checkered floor below or holding a coffee cup and newspaper or in striped sweaters and skirts, sitting or supine, out of context and also locatable to that triangular space. He painted vistas through windows, still lifes of the match strike or pair of scissors or glass of water on his table. On occasion he drew portraits of friends and captured the likeness of his wife Phyllis over and over. He could open his back door and look down to the bar of Club Triangle.

Rachel Federman, Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Drawings at the Morgan Library & Museum, writes on the potential effect noise had on the artist’s work of the time:

“When as a young man he first encountered Cézanne’s pictures in reproduction, he found them ‘a little bit repellent.’ Perhaps it was for this reason that they ‘hit [him] very, very hard.’ Ever self-aware, he observed, ‘I temperamentally was very, very far from Chagall, who can have somebody flying or upside down….There was a certain sense, a certain logic, about this figure is going to be in such and such an interior, and the light is going to be in a certain way, and it’s going to be a woman. It was the exuberance of music that seems to have prompted Diebenkorn to incorporate it into his studio practice in 1954, shortly before he shifted definitively to representation. He later offered a suggestion of how listening to music affected him: ‘I’m not going to be able to really describe this. [But Beethoven] does a really non-art kind of thing, and deals with it so deftly….There’s all sorts of rambunctious music. [But] he’s the only one who can be rambunctious like—like somebody talking in a bar….I don’t know anyone who has done it as strikingly as Beethoven, this thing…I would hope sometime to feel that my expression could do that thing.’ Although we remain aware of Diebenkorn’s efforts to uphold the ‘fitness’ of his pictures—there is always the sense that he is weighing options, problem solving—in representational drawings in particular, we sometimes find him approaching the tenor of ‘talking in a bar,’ which is to say, a bit more loosely, more familiarly than is typical.”17

Federman continues:

“Diebenkorn’s studio at this time was adjacent to a working-class bar where he often met with visitors. When he likened the rambunctiousness of Beethoven to somebody talking in a bar, he may have been thinking of moments like the ones he had there, with the concerns of the studio left behind momentarily, but still close at hand. If the quality he so admired in Beethoven’s music, and which he hoped to achieve in his work, is to be understood through his own metaphor, then he succeeded on several counts. The body of work he produced in these years is deliberate and considered, its dialectic of control and release ever present, but it is also deeply familiar, at times verging on playful—rambunctious, even.”18

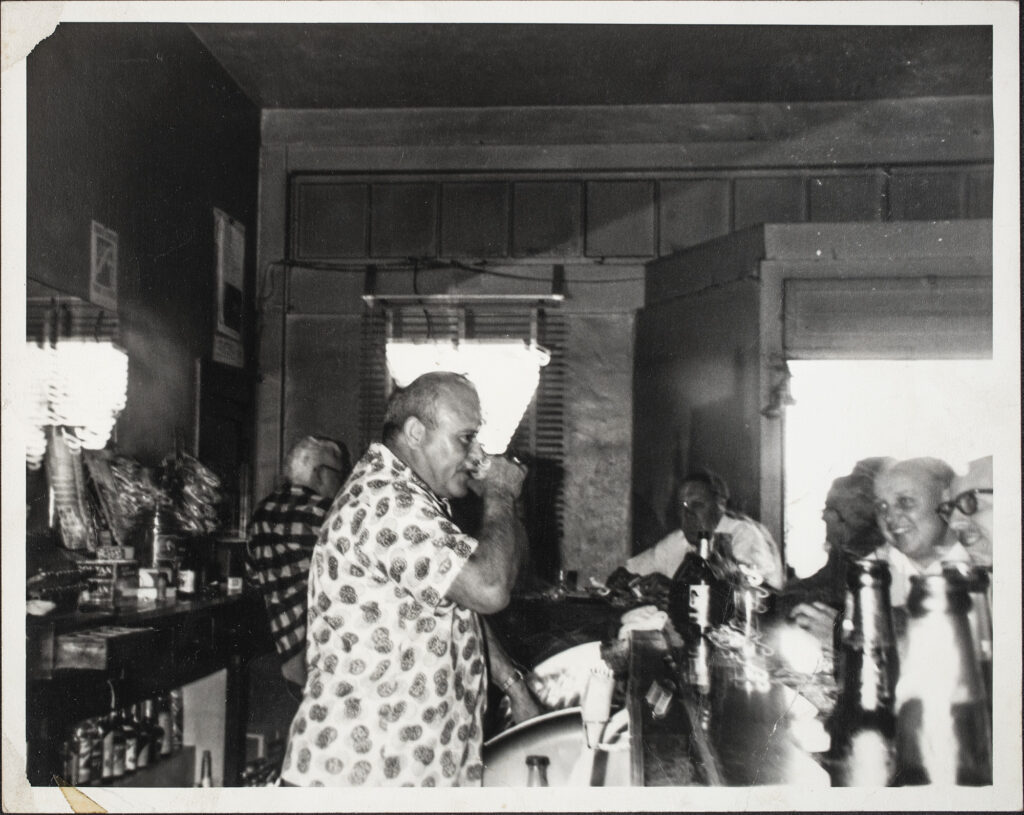

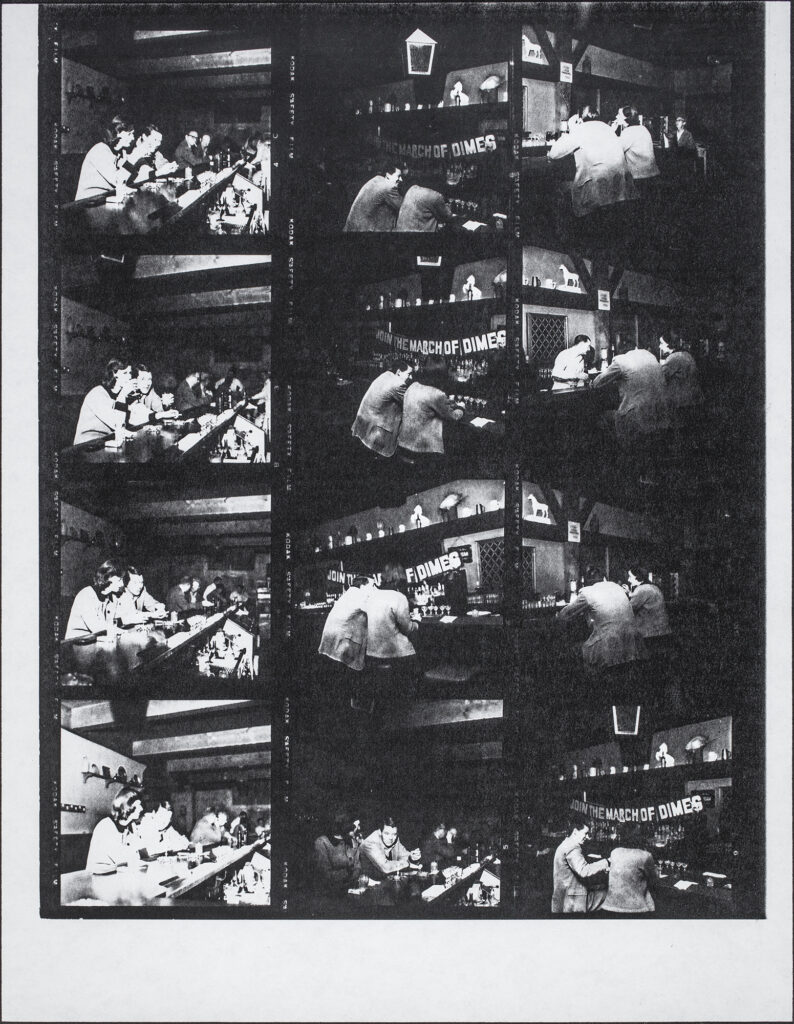

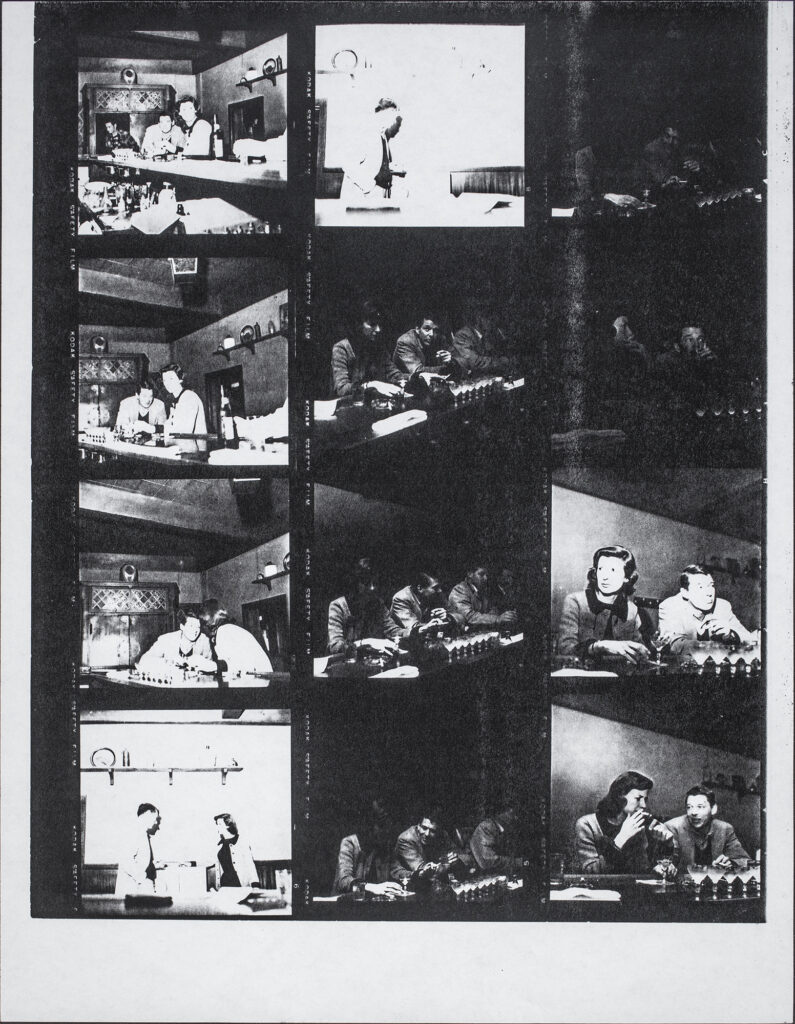

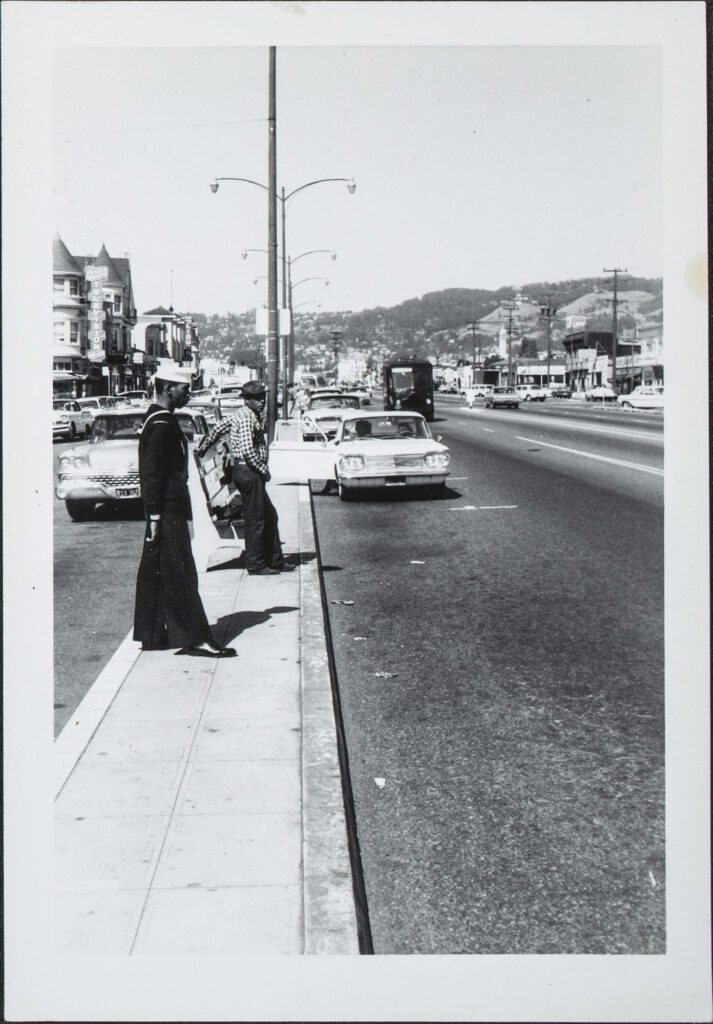

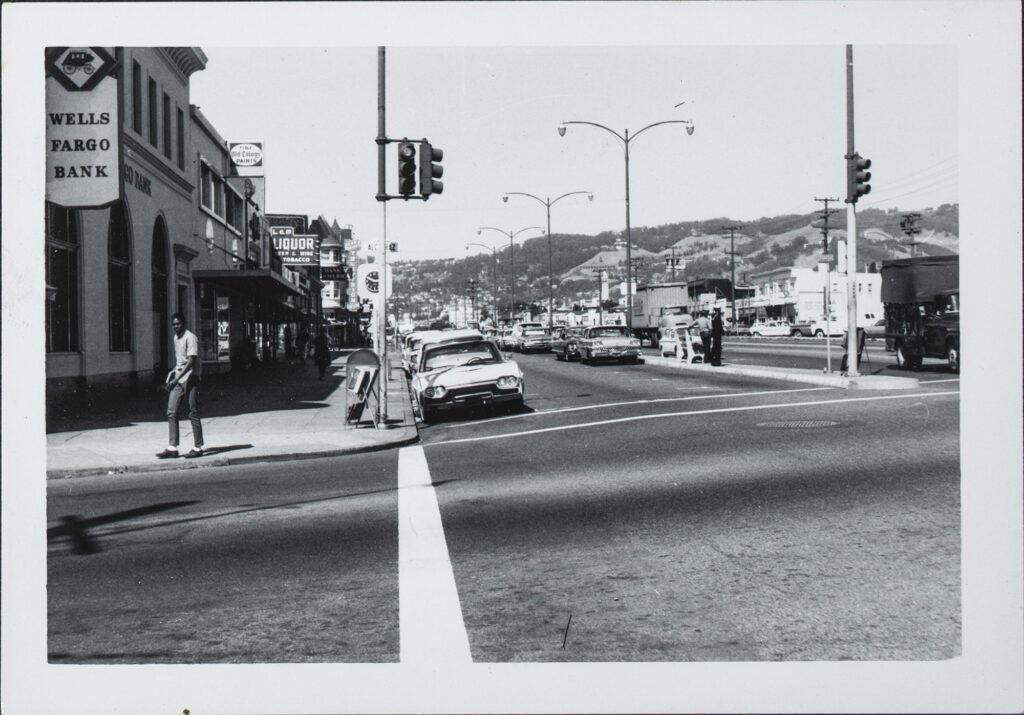

Northcutt and I also surfaced recently digitized photographs in the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives of the street corner, the building’s interior and exterior, and surrounding streets, all now available on diebenkorn.org, the encyclopedic public resource on the artist. A notable holding is a set of Xerox copies of photographs taken by Hans Namuth in 1958, which suggest a day in the life of Richard Diebenkorn, starting at his home in the Berkeley hills, stepping into his studio in the backyard, taking his dog for a walk near the Claremont hotel, driving in their convertible station wagon, and sitting with his wife Phyllis at a bar with the same beadboard wainscotting and floating bookshelves of his Triangle Building studio. They wear similar clothes across images, further supporting they were taken on the same day, and likely were photographed inside Club Triangle in 1958, which makes these photographs some of the only surviving interior shots of the establishment.19 The images show the artist’s studio interior as well as the view from its window, which looks out to a small triangular-shaped meridian (850 61st Street) and a metal gas station at the gore point.20 Beyond, there were other commercial buildings and the University of California, Berkeley, Campanile in the distance. The artist’s daughter, Gretchen, remembers walking down the street with her father to buy cheese blintzes from a local Jewish delicatessen.21

Today the triangular lot is part of a public park and community gathering place, called Driver’s Plaza, bounded by the streets 61st Street, Genoa Street, Stanford Avenue, and Adeline Street. The plaza was created as part of the implementation of Oakland’s Stanford/Adeline Redevelopment Plan adopted in April 1973.22 The remaining structures on the parcel were cleared around that year to make way for the park, and prior to adoption of this plan, 61st and Genoa Streets connected through the plaza. As Mr. Hausler noted, “The plaza is mostly paved with patches of grass and a few trees. It also contains a sheltered bus stop and a portable toilet,” and is a place “where community groups dole out free meals and services to those in need.”23 The oral history account related to the Triangle Building studio being condemned in 1965 for public transit was unable to be verified, and while the route maps for the Bay Area Rapid Transit were reworked on several occasions over a ten year period, the records do not show them slotted for those streets.24 Instead, summary reports detail the public transit system running one block to the east on Grove Street (now called Martin Luther King Jr. Way).25

Geography was important to Richard Diebenkorn. The surrounding landscape seeped into his art, sometimes consciously, many times subtly and partially referenced, and he mixed his work with a color sensibility and an amalgam of impressions from the places he lived and worked. For a brief period in the history of Club Triangle, Richard Diebenkorn painted next door to the comings and goings of the neighborhood. He enjoyed going somewhere to make his art. He enjoyed the activity of regulars stopping into the bar. He liked frequenting local shops and storefronts and looking at the facades of old buildings. He liked the history and age of spaces. From 1958 to 1965 he made some of his most successful figurative paintings, completing over two hundred canvases (out of roughly two hundred and ninety made during his ten-year figurative period). Diebenkorn and his family have either lived in the area or maintained a studio there since the early 1950s, with the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation offices continuing the geographic legacy.

Thank you to all who assisted and contributed to the research of this project, including Jacquelyn Northcutt, Gretchen Diebenkorn Grant, staff at the Oakland History Center, Emeryville Society, Sean Dickerson at the African American Museum & Library, Donald Hausler, Betty Marvin, and Daisy Murray Holman. We hope the story will continue.

1. Richard Diebenkorn quoted in Maurice Tuchman, “Diebenkorn’s Early Years,” in Richard Diebenkorn: Paintings and Drawings, 1943–1976, exh. cat. (Buffalo: Albright-Knox Art Gallery, 1976), 24.

2. “Another thing that really affected me was a studio I had in Berkeley. It was a triangular room at the back of a tavern; I could open a door and look right down the bar at all of the regulars.” Richard Diebenkorn quoted in Dan Hofstadter, “Almost Free of the Mirror,” New Yorker, 7 Sept. 1987, 61.

3. Elinor Poindexter, letter to Richard Diebenkorn, 7 Mar. 1958, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

4. Richard Diebenkorn, letter to Elinor Poindexter, Mar. 1958, Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives © Richard Diebenkorn Foundation. No record of Diebenkorn’s Guggenheim application, other than a blank application form in the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives, has been found. He later served as a juror for the Guggenheim Foundation from 1979 to 1983.

5. Richard Diebenkorn, oral history interview with Susan Larsen, 2 May 1985, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

6. Phyllis Diebenkorn, an interview conducted by Benjamin Grant, grandson of the artist, 2003–04, Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives © Richard Diebenkorn Foundation.

7. The artist attended Stanford University from 1940 to 1943 before being called to active duty in the Marine Corps during WWII. The university later awarded him a bachelor’s degree in 1949. Mendelowitz wrote a letter in support of the appointment. Daniel Mendelowitz, letter to Richard Diebenkorn, July 1963, Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives © Richard Diebenkorn Foundation.

8. Richard Diebenkorn kept the Triangle Building studio while he worked at Stanford University from Fall 1963 to Spring 1964. His wife Phyllis recalled that he may have rented the space to a friend, possibly Adelie Bischoff, during their temporary time away. P. Diebenkorn, an interview conducted by Benjamin Grant.

9. Between 51st and 63rd Streets, the BART line ran in the street meridian as an aerial transit line on Grove Street (now Martin Luther King Jr. Way). “The same mode of construction is continued northward along Adeline Street to the Ashby Avenue Station, which is located in the center of the street, approximately midway between Woolsey Street and Ashby Avenue. From the station, the line continues northward along Shattuck Avenue to Derby Street, which marks the beginning of a transition from aerial structure to subway, the subway portal being located at the south side of Dwight Way.” In 1965 the City Council of Berkeley reviewed the public transit plan, considering studies for widening Grove Street or for establishing a one-way couplet with an adjacent street in conjunction with future traffic projections. The report recommended widening Grove Street to include four lanes and two parking lanes. Parsons-Brinkerhoff-Tudor-Bechtel, The Composite Report: Bay Area Rapid Transit (May 1962), 48; Wallace Johnson, City Council Report (Berkeley, CA, Feb. 1965), 39–42.

10. His research has been invaluable. Donald Hausler, “The Long, Strange Trip of North Oakland’s Club Triangle,” Journal of Emeryville Historical Society, XXXV, no. 2 (Summer 2024).

11. Hausler, “The Long, Strange Trip of North Oakland’s Club Triangle,” 6.

12. “Block of Buildings Burns,” Oakland Tribune, 18 September 1967.

13. Application for Permit to 6031 Adeline, submitted by V.E. Mattox to the Building and Housing Department, City of Oakland, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1gZfG15ptgPj_OJmPj35pkN1ixS-zFb5k/view.

14. Hausler, “The Long, Strange Trip of North Oakland’s Club Triangle,” 11.

15. “Mr. B’s Triangle,” The Berkeley Gazette, 15 December 1969, 1.

16. “There was a lot of rather useless furniture built into the wall, and when I pulled it off you could see many different overlapping layers of house paint. The effect was fascinating.” Diebenkorn, “Almost Free of the Mirror,” 61.

17. Rachel Federman, “Talking in a Bar: Richard Diebenkorn’s Representational Drawings 1955–1967” in Richard Diebenkorn: Works on Paper, 1955–1967, exh. cat. (New York: Van Doren Waxter, 2017), 4.

18. Federman, “Talking in a Bar: Richard Diebenkorn’s Representational Drawings 1955–1967,” 6.

19. The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation was unable to verify whether the 1958 photograph of Richard and Phyllis Diebenkorn inside at a bar was indeed Club Triangle. The Hans Namuth estate was unreachable, and the holdings at the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona did not contain any caption data on the back of their images.

20. “Driver Plaza,” Oakland Wiki, https://localwiki.org/oakland/Driver_Plaza.

21. Gretchen Diebenkorn Grant, interview with Katharine James, 16 May 2024, Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives © Richard Diebenkorn Foundation

22. “Stanford/Adeline Redevelopment Plan,” City of Oakland, adopted April 10, 1973, as amended December 14, 2007, https://oaklandca.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/oakca1/groups/ceda/documents/report/dowd008247.pdf.

23. Hausler, “The Long, Strange Trip of North Oakland’s Club Triangle,” 11.

24. In 1963 the newly elected Berkeley mayor, Wallace Johnson, coalesced public opinion to challenge the BART plan: “A graduate of the California Institute of Technology with an engineering background, Johnson took a close look at the rapid transit plan for Berkeley and determined that putting just the central area under Shattuck Avenue underground was not good enough for his city. Johnson publicly denounced the planned aerial structures in the engineers’ renderings as a potential eyesore, calling them ‘aesthetically unattractive.’ More important, he featured that the elevated tracks leading into and out of the city and the two elevated stations would divide the city psychologically along racial lines. The future route would run parallel to Grove Street (now Martin Luther King Jr. Way), an unofficial dividing line between predominantly white neighborhoods to the east and black neighborhoods to the west. Johnson also believed the elevated line would negatively impact businesses along the route.” 96. Michael C. Healy, BART: The Dramatic History of the Bay Area Rapid Transit System (Berkeley, CA: Heyday, 2016), 96.

25. Parsons-Brinkerhoff-Tudor-Bechtel, The Composite Report: Bay Area Rapid Transit, 48.