Artsy: A newly expanded interview with Sasha Nicholas, author of “Everything All at Once: Richard Diebenkorn and Postwar American Art”

Presented alongside an online exclusive exhibition curated by Nicholas

May 5, 2020

New York, NY

Last fall, Rizzoli New York introduced Richard Diebenkorn: A Retrospective, the most comprehensive monograph yet on the distinguished American painter, draftsman, and printmaker for readers of all backgrounds and levels of interest.

The book features a fresh voice in art history, Sasha Nicholas, who brings the artist alive and anew in a fascinating and visual essay so that audiences are able to, as she says, understand the artist “not as a solitary figure who worked in isolation,” but rather, as a painter whose career was deeply intertwined with events in postwar America.

An exclusive to Artsy, Richard Diebenkorn Foundation is delighted to publish for the first time here an expanded interview with Ms. Nicholas that first appeared on diebenkorn.org. This is accompanied by an online exhibition curated by Ms. Nicholas specially for Artsy.

What was your reaction when you were asked to write the essay?

I was thrilled of course, but you know, “No pressure!”

This was a challenge that was both exciting and very daunting. There have been many terrific texts on Diebenkorn, such as Jane Livingston’s in the artist’s catalogue raisonné (Yale University Press, 2016), to the many monographs. I felt that I had to write something different, to look for a new approach to the artist and hopefully draw in a new audience.

You very vividly bring him to life on the page as an artist and a person. In fact, you remark early on that he “reinvented his aesthetic when it began to seem fashionable or effortless” and “was compelled by a deeply personal code of intertwined ethical and artistic convictions.”

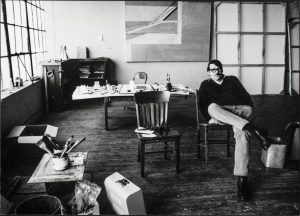

I did not know Richard Diebenkorn, and so my aim, in part, was to help readers feel strongly connected to his sensibility, just as I came to feel this over the course of the project. I tried to capture, as best I could, his tenacious, perfectionistic, and strong-willed personality and how it informed the work. He himself tended to be reticent when it came to his art. He did not want to be pinned down, so he let the work stand for itself. He did not want to be fashionable. He was an independent spirit. The idea of an art that was very calculated and avant-garde was antithetical to the person he was.

Throughout the essay, you talk about the tension between abstraction and representation, and as you write, his “insisting on multiple ways of seeing” which ensured that his work “transcended its historical moment.”

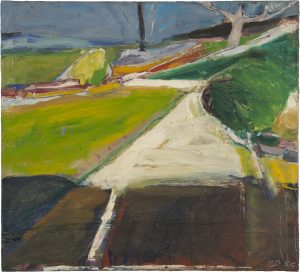

Diebenkorn evaded easy classification. He was multifarious and a shape shifter. Very few postwar artists moved across the spectrum of aesthetic approaches, experimenting with abstraction, representation, and everything in between, as fluidly as he did. This was highly intentional on his part. By continually challenging himself in this way, he made sure his art never felt dated or mechanical. It was always fresh.

His “risky and startlingly fluid movement” between these modes occurred in a time of heated arguments in the art world and his nonconformism, as you assert, “sometimes landed his work in the margins of postwar histories.” What was happening in the 1950s, and why was that important for you to convey to the reader?

Diebenkorn came of age as an artist in a time when there was tremendous pressure to embrace abstraction. It is easy to lose sight of how radical it was for him, at the apex of his great public success with his abstractions in the 1950s, to abruptly do something different, to shift to a painterly representational style, focusing on figures, Bay Area landscapes, and still lifes. It was an audacious move to reinvent himself, especially so early in his career. I find it incredibly inspiring. Many of us want to reinvent ourselves in such a bold way at times, but it’s very difficult to do.

In the 1950s, American art—specifically American abstraction—arrived on an international stage, whereas it had never been taken very seriously before. There was excitement among many American artists about being associated with this national movement, about belonging to something so significant and influential. But Diebenkorn got itchy at this idea. That is not who he was aesthetically and philosophically. He did not want to be a part of an “ism.” He rejected the idea that his art might become simply a hallmark style to be restated again and again.

In the 1950s, American art—specifically American abstraction—arrived on an international stage, whereas it had never been taken very seriously before. There was excitement among many American artists about being associated with this national movement, about belonging to something so significant and influential. But Diebenkorn got itchy at this idea. That is not who he was aesthetically and philosophically. He did not want to be a part of an “ism.” He rejected the idea that his art might become simply a hallmark style to be restated again and again.

Of course, art history itself has undergone a transformation in recent years. We have seen modern art histories expand to include pioneering artists who did not neatly fit into the traditional narratives. This process has been really exciting for young artists, and for historians. We’ve discovered that the canonical stories that many of us were taught are vastly more diverse, messy, and complicated than we’d imagined. Postwar American art, for example, was filled with fascinating and influential artists whose work was sidelined if it didn’t adhere to the dominant stylistic categories of Abstract Expressionism, Pop, and so on.

For those who aren’t very familiar with Diebenkorn, I think the first impulse might be to imagine him as one of the many white male postwar painters who devoted himself to large abstract paintings predicated on equally grandiose themes, a story many of us know well. But this was not Diebenkorn’s story. He was profoundly opposed to stylistic rigidity and to making epic claims for his art. When he began painting figuratively in the mid-1950s, it was considered a ghastly thing to do. But he wanted to try on a different creative approach. That kind of experimentation is something you see very often now—it almost goes without saying that young artists today draw upon a range of styles and media. Diebenkorn was also prescient in his attraction to things that were deemed to be totally outmoded and obsolete. This is something you see a lot in contemporary art—rather than obsessing over the “new,” artists often look to styles and subjects that are nostalgic, a little old fashioned, even awkward or ugly, and find new life in them, just as he did.

You make the point that although he was always independent and “shied away from Abstract Expressionism’s heroic claims,” he was influenced by key members of the AbEx movement, and yet he said he was “really a traditional painter, not avant-garde

at all.”

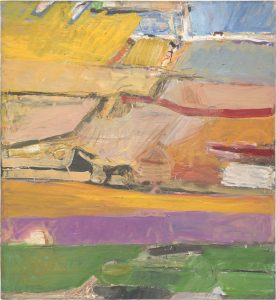

Richard Diebenkorn looked really hard at Abstract Expressionist painting, as so many did in his generation. Clyfford Still (d. 1980) was especially important early on. Still taught at the California School of Fine Arts when Diebenkorn was a student there, and his early palette was inspired by Still’s intense reds, blacks, and ochres. There was an Arshile Gorky (d. 1948) retrospective in San Francisco that he saw very early on, and he emulated the artist’s calligraphy and turbulent brushwork. It is not coincidental that Diebenkorn met Willem de Kooning (d. 1997) in New York just before he began the Berkeley paintings, and his paintings then became very ambitious and gestural. But although Diebenkorn was stimulated by these artists, he never imitated. He transformed what he saw into his own vision, such as Berkeley #52, 1955, with its open areas of lush, broadly swept color. The formal and chromatic ambition of works like this one earned him a place in some of the era’s major exhibitions of Abstract Expressionist painting and recognition by critics, like the movement’s chief theorist Clement Greenberg.

Let’s turn to your theme of the artist’s search for “rightness,” which he himself mentioned in his studio notes and interviews, and of course in his remark in 1986 to John Gruen that, “Now, the idea is to get everything right—it’s not just color or form or space, or line—it’s everything all at once,” that would famously become the title of Gruen’s article for ARTnews.

I actually struggled with this notion of “rightness,” which sounds dogmatic, and of course Richard Diebenkorn typically reacted against dogma. It was a very personal idea: how a work would achieve rightness. I think it meant to him, in part, that his work needed to be hard fought. I’ve talked about this a bit already. Diebenkorn was by nature an incredibly elegant, sure-handed painter. But he had been convinced by his close friend and fellow Bay Area artist David Park (d. 1960) that art should be hard-hitting, even coarse and awkward at times. Park called paintings like this “troublesome pictures.” Diebenkorn’s sense of rightness was bound up with his art not being easy. He felt compelled to make paintings that raised questions, that were challenging, enigmatic, and at times troubling, even if they were also beautiful. This was an ethical position for him.

Throughout the essay, you situate the artist and the work he was making within the particular time in postwar America, such as the contemporary art scene in Los Angeles in the 1960s, where he was interacting with the Light and Space artists, including “the sleek, hard-edge Finish Fetish epitomized by [Larry] Bell’s (b. 1939) crystalline glass boxes or [Craig] Kauffman’s (d. 2010) plastic wall sculptures.”

Of course, the move in 1966 to Los Angeles did transform Diebenkorn. We tend to think about his shift to the Ocean Park paintings at this time as relating to the landscape, to Santa Monica, to the industrial geometry of his new studio there, and to the very bright Southern California light. While these factors were essential, I think it’s valuable to remember he was working in a neighborhood populated by a younger generation of artists who were revolutionizing the Los Angeles art scene. A lot of these artists were thinking about the same kinds of issues as Diebenkorn and there was influence in both directions. Light and Space was about the work of art not being just a contained, inert thing. It called attention to how our vision responds and changes in relation to a work of art, how a work engages our body as we move around it, how a work interacts with the space and environment it’s in. I wanted to think about Diebenkorn’s Ocean Parks as initiating a dialogue with those issues as well.

Your essay includes, literally, many radiant and sublime works, such as #22 (Albuquerque), 1951 and Untitled (Yellow Collage), 1966. Do we dare ask you to remark on a single work that for you expresses your feelings about the artist?

Woman in Profile, 1958. It operates on multiple levels, and it epitomizes that tension between abstraction and representation which is so crucial to Diebenkorn’s work. If you took out the figure, you would almost have the tapestry-like weave of geometry that you see in the Ocean Park paintings. But then you can’t take your gaze off of the figure. There is incredible tension between this very expansive landscape and the isolated female figure, whose body is very much pushed against the canvas surface, penned in by the window mullions. She’s almost ghostly with that intense, mask-like wash of light on her face. So this is a tranquil, peaceful moment, but it is also more than a bit eerie.

In fact, you refer to the canvas Woman in Profile, 1958, as one of the most iconic of his representational oeuvre, belonging to a body of “monumental canvases depicting the figure in architectural settings, often with a view to the outdoors,” that recall the paintings of Edward Hopper (d. 1967), whose work we know Diebenkorn admired.

Diebenkorn’s figurative paintings, like Hopper’s, capture these moments of everyday solitude that are at once serene and poignant.

Much has been written on the impact of Matisse and other French painters on Diebenkorn’s figurative works, and I wanted to add to this by exploring Hopper’s influence, which is perhaps not as obvious. Diebenkorn looked carefully at Hopper when he was a young student and made early works that closely emulated his style. Many of his later figurative paintings continue to share Hopper’s cinematic quality, and the tantalizing hint of a narrative that is offered but also withheld. In both artists’ work, architecture and light become conduits of human emotion—the way light moves through a landscape or an architectural space is as expressive as the figure.

We often look at Diebenkorn’s figurative canvases—just as we do Hopper’s—and wonder if these are scenes of meditative solitude, which might be something to savor, or are they expressing something more doleful: loneliness, alienation, melancholy. Perhaps it is both. I think these works capture how the modern world, despite all of its hustle-bustle and interconnectivity, can lead us to turn inward, for better and for worse.

I have been thinking about Virginia Woolf’s From The Lighthouse. There is a passage when the character Mrs. Ramsay sits down to knit, and in the solitude of this very ordinary moment, she is able to connect to her innermost self. Woolf writes: “All the being and the doing, expansive, glittering, vocal, evaporated; and one shrunk, with a sense of solemnity, to being oneself, a wedge-shaped core of darkness, something invisible to others.” I think Diebenkorn’s figurative canvases portray this same kind of moment. Being alone, especially in the most mundane routines of everyday life, can ground us in a core sense of ourselves that is simultaneously comforting, haunting, and ineffable. In our own ways, we all experience this. And so we feel ourselves in these works.

For more information, please visit Rizzoli.

Explore the title and talk with us on Instagram @diebenkornfoundation, @rizzolibooks, and @trifoliosrl.