Albuquerque and the Support of Women: Jo Kantor and Phyllis Diebenkorn

By Daisy Murray Holman

April 9, 2019

In the soft light of a New Mexican adobe house, where I had the good luck to see my first Diebenkorn painting [in 1951], the image was of sandiness and desert: a horizonless flow of pale yellows, ochres and sand whites….The painting…reflected not only his poetic grasp of the landscape before him, but also where he had been before. His studies at the California School of Fine Arts during the late 1940s had coincided with the advent of Clyfford Still and Mark Rothko. It was natural for him to explore new proposals for the projection of limitless space. He carried the experience with him to New Mexico. It is only one of Diebenkorn’s special talents to preserve and enrich experiences, evolving steadily at a harmonious pace. I don’t think he has ever left the desert behind.

—Dore Ashton, “Richard Diebenkorn’s Paintings,” Arts Magazine, Dec. 1971–Jan. 1972, 35.

From January 1950 to June 1952, Richard Diebenkorn lived in Albuquerque, New Mexico, with his wife Phyllis and their two young children. On track to complete his master’s degree at the University of New Mexico in the spring of 1951, the family made the decision to remain in the Southwest for as long as they could support their adventure.

The year 1951 proved to be a pivotal one for the artist’s career, not only because of the mature paintings he was producing, but also because those very works were being seen and talked about by key art individuals in California and New York. The prospect of sales and gallery representation encouraged Richard and Phyllis’s dream of remaining on the mesa. Instead of giving in to the pull to return to California or venture to New York, Diebenkorn and Phyllis committed to the desert and the happiness and creative freedom they found there. The isolation benefited the artist, and he worked with determination and focus, unbothered by the interest in him that was building among collectors, critics, and other artists.

Throughout Diebenkorn’s life, women played a pivotal role in shaping his career. During the Albuquerque years, three women in particular were crucial: critic Dore Ashton, gallerist Josephine “Jo” Kantor (later Morris), and his wife, Phyllis Diebenkorn. In this segment of From the Basement, we dig into the correspondence from Jo Kantor and Phyllis Diebenkorn. The letters outline Jo’s influence in spreading the “gospel of Diebenkorn,” while the intimate exchanges between Phyllis and her husband give us a glimpse of the young couple as they developed and secured a partnership in his career. In these rich series of letters, newly digitized and part of the Richard Diebenkorn Archives, the two women’s support of the young artist and their investment in his success snap into focus.

Jo Kantor

Richard Diebenkorn’s first solo show at a commercial venue took place in 1952 at the Paul Kantor Gallery in Los Angeles (operated jointly by Jo and Paul), but the relationship between the artist and the gallerists began in 1949 when the Kantors first encountered Diebenkorn’s work at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in the exhibition California Centennials Exhibition of Art. Diebenkorn’s inclusion in this show demonstrates how powerful the exposure from a group show can be for a young artist. It was through this show that curator Gerland Nordland as well as other important figures in the Los Angeles art scene, such as James Byrnes, William Valentiner, James Breasted, and Arthur Millier,1 first recognized Diebenkorn as an artist to follow, collect, and actively promote.

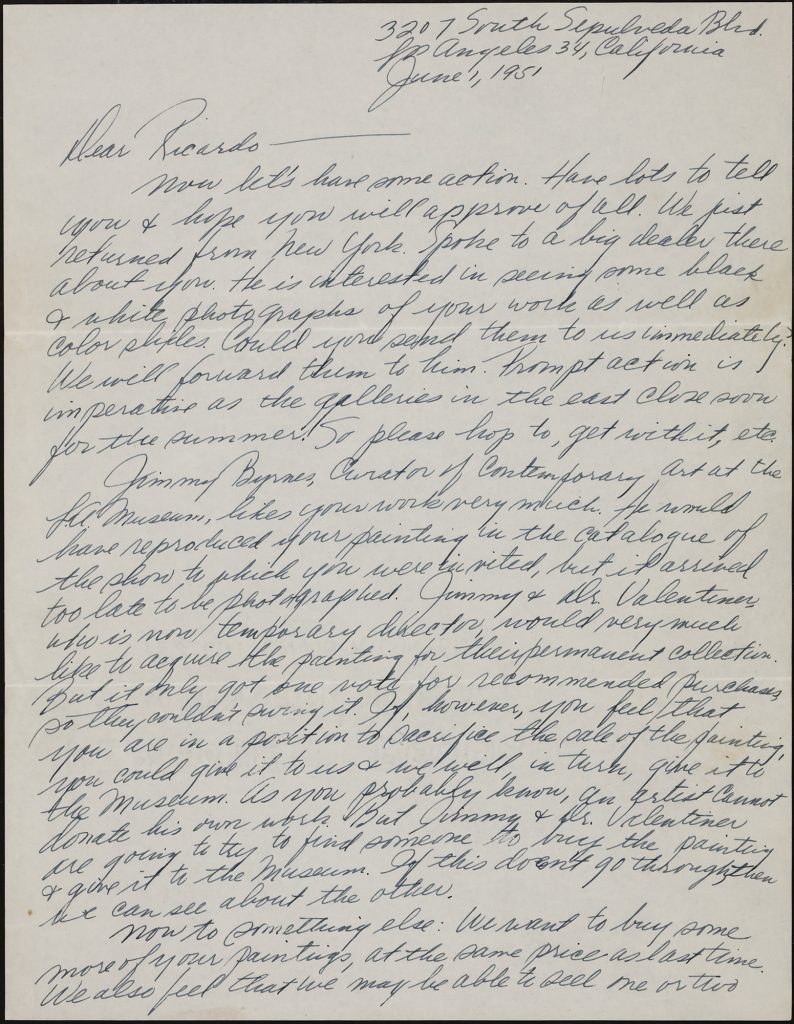

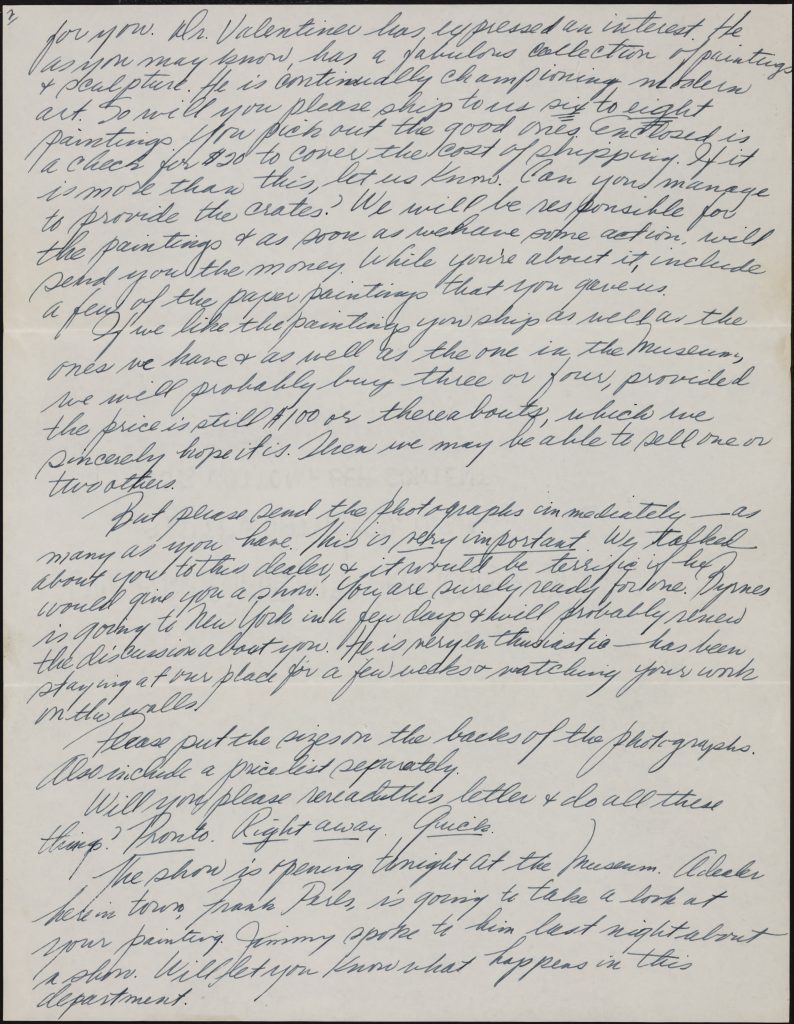

The Kantors began collecting Diebenkorn’s work as soon as they could, either in 1949 or 1950. At the time the Kantors did not yet have an established gallery, but took it upon themselves to promote Diebenkorn anyway. In a June 1st, 1951, letter from Jo Kantor to Richard Diebenkorn, she writes, “Now let’s have some action,” asking the artist to hurry up and make some color slides that she can send to New York. The letters, mostly authored by Jo, laid out the Kantors’ goal to represent Diebenkorn and show his work beyond California. Jo sketched out a plan to get Diebenkorn’s paintings in front of the eyes of gallerist Sam Kootz, Museum of Modern Art director Andrew Ritchie, and curator Dorothy Miller. While Diebenkorn was not shown in New York until 1954 (at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum), Jo tells a story of building interest. These letters are the primary record of Diebenkorn’s work having been seen by those individuals in New York between his brief time in Woodstock in 1947–48 and his Manhattan summer in 1953. The 1953 summer months they spent in New York were a trial period: Diebenkorn believed there was a ready audience for his work there, and he wanted to know if he could be happy living in America’s epicenter for art.

Jo’s voice is excited and self-aware, laughing at times at their artsy Hollywood life but effusive about her belief in Diebenkorn’s rare talent. It is clear that Jo and Paul Kantor loved his paintings with earnest. “You are being previewed tomorrow night,” Jo writes in closing a letter on June 21st, 1951. “Some friends will be over, Valentiner among them. Only extra special high-class intellectuals will be allowed. A geiger counter geared to aesthetic appreciation will be installed at door. Will let you know reaction.”

Jo Kantor purchased a number of Diebenkorn’s works in the 1950s. They were mainly from the Albuquerque period, including the painting Miller 22 and other works on paper. She also owned one pivotal work from 1946, Advancer, and a large Berkeley abstract painting. Jo owned these works until her death in 2002.

Phyllis Diebenkorn

At no point in Diebenkorn’s career did he act alone. Phyllis acted as a representative of the artist on numerous occasions, serving as his eyes, ears, and voice from the first moment of potential gallery representation. During a 1951 trip to see her mother in Southern California, Phyllis spent a few days in Los Angeles with the Kantors. It was Phyllis who really established an in-person relationship between the Kantors and the Diebenkorns. Without her positive review of the couple, it is unlikely that they would have continued to work with each other and allowed them to represent Diebenkorn and sell his art.

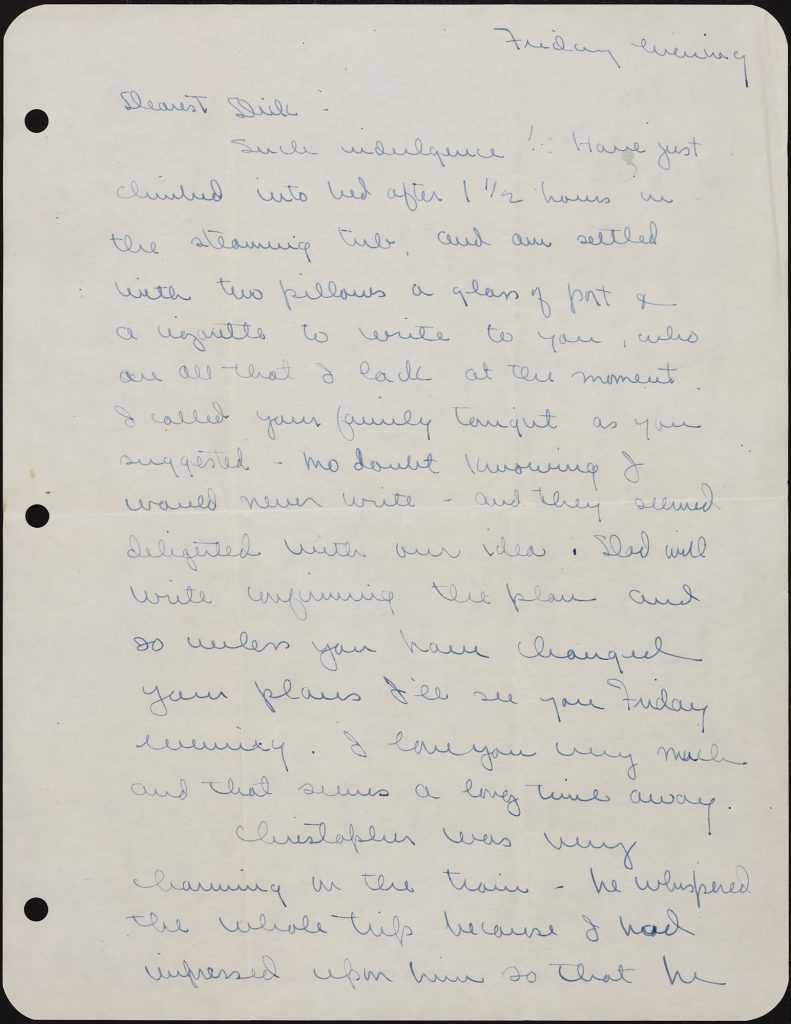

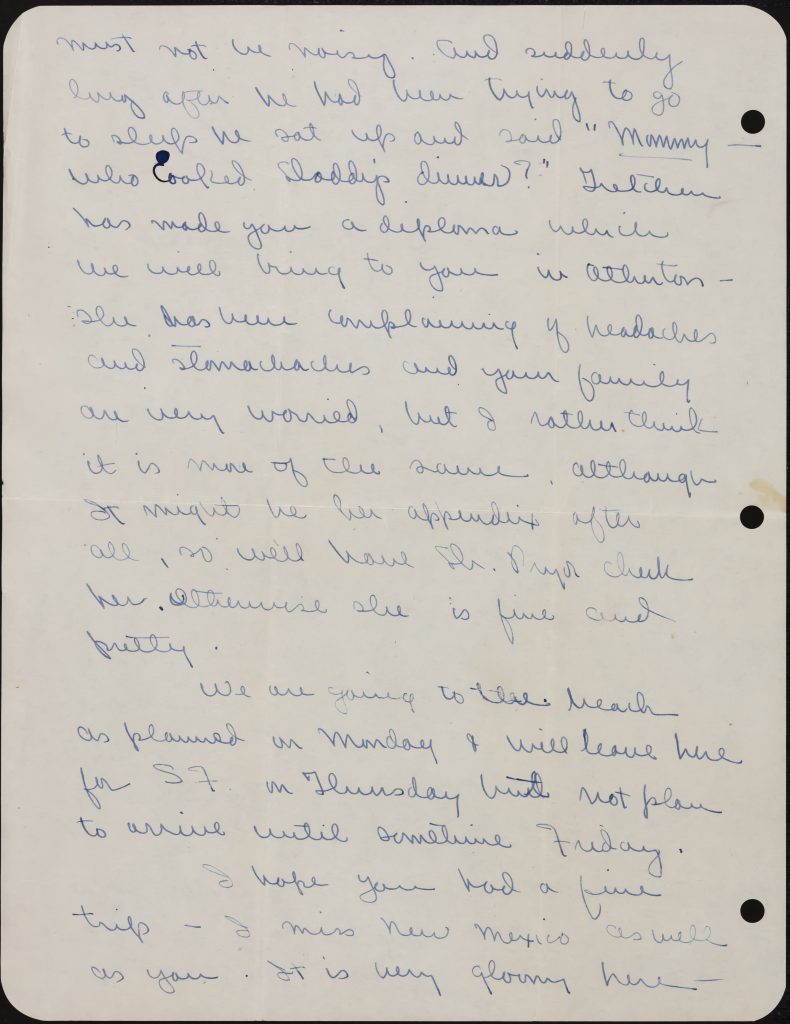

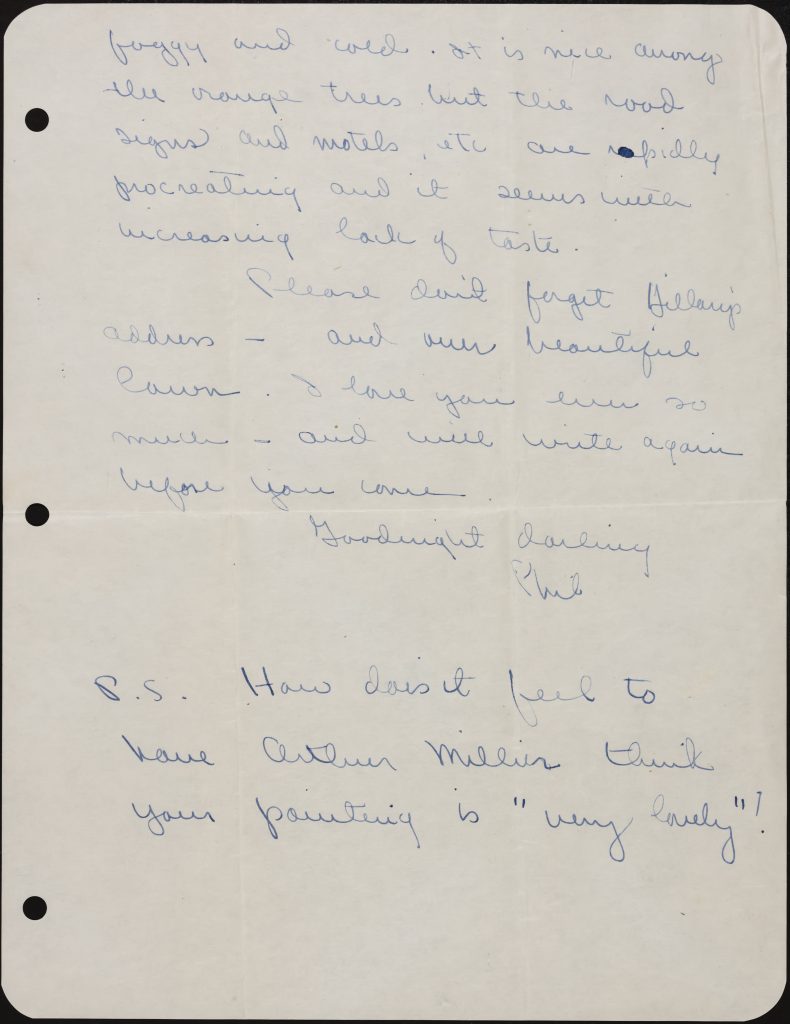

The correspondence between Richard and Phyllis in the summer of 1951 communicates one primary thread: Phyllis’s love of their New Mexico life. In a June 9th, 1951, letter sent from her mother’s home before her visit with the Kantors, Phyllis writes, “I miss New Mexico as well as you. It is very gloomy here—foggy and cold. It is nice among the orange trees but the road signs and motels, etc are rapidly procreating and it seems with increasing lack of taste . . . I love you ever so much—and will write again before you come. // Goodnight darling // Phil // P.S. How does it feel to have Arthur Millier think your painting is ‘very lovely’!”2

Later in the month, a long letter from Phyllis to Diebenkorn places her in the midst of the social aspects of the art world, but also includes details about pricing and the market. In a June 25th letter, she describes visiting a wealthy collector in Hollywood who possessed an attitude she found disagreeable. She writes, “The Kantors of course aren’t like this. They seem to be genuinely interested in your work and most of the things they have are very interesting. They are apparently friends with Ynez Johnston—told me about her analyst, etc and have a couple of her things, but except for that there aren’t too many links with these other people. They were wonderful to me3—took me to dinner at a glamorous spot on Wilshire Boulevard—plied me with scotch. No one apparently drinks anything but scotch—and they respected my statement that I wasn’t there to act as a representative for you.”

Phyllis goes on to update Diebenkorn on the developing relationship with Sam Kootz. The Kantors tell Phyllis that if Kootz isn’t interested, they will try Betty Parsons next. It appears that they are still figuring out whether or not they will have a gallery space, and thus selling the work is spoken of in a casual way. This does not sit well with either of the Diebenkorns.

“I wish I could feel better about all this. Except for the Kantors I feel that these people are really desperate and represent an element in our society which is infinitely worse than the sort of solid middle class atmosphere we so often deplore….

P.S. I hope you can wait to write the Kantors until I get there but if they have to know something right away it is my feeling that you shouldn’t consider making any “prices.” If you do with these people that sort of thing will always have to be done—they apparently feel obliged to work this way—I don’t know whether they will ever buy any or not and I don’t care. It is not worth it to be involved. I love you and I’m so glad we’re living in Albuquerque.

In a June 26th, 1951, letter Richard replies to Phyllis, “What in hell is all this reduced price business? I think your feelings are right—but what about the one to Valentiner? Do you think its like real estate? Should I say 200? Is it the big grey painting? This is silly because we can talk about it.”

The two are not yet 30, living on the GI Bill, and every penny counts. However, they are also a young couple enjoying their family and friends, living on their own, and feeling a clear love and affection for each other. After regaling Phyllis with the details of his fishing trip, Diebenkorn closes the letter in a flurry of adorations, mixed with the real life nitty-gritty of every married couple. He signs off with his college nickname, writing, “I miss you VERY very much. Had been counting on seeing you tomorrow….Awful glad money came. One dollar in pocket. Are the Kantors going to buy? // Love you VERY very much….Love to children. Love you again, Witz. // P.S. $15 for drwg. O.K.?// P.P.S. Swell thunderstorm out. // P’’ Miss you again.”

1. Valentiner and Breasted were co-directors of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Byrnes was the curator of painting at the museum. Millier was an art editor and critic for the Los Angeles Times.

2. Art critic Arthur Millier wrote about Diebenkorn’s painting Miller 22 (1951) in a Los Angeles Times review on June 3, 1951. Jo Kantor would buy Miller 22 that same year.

3. Ynez Johnston was a friend of the Diebenkorns from San Francisco.