As Seen By: Leo Holub in the Studio

By Daisy Murray Holman

August 25, 2021

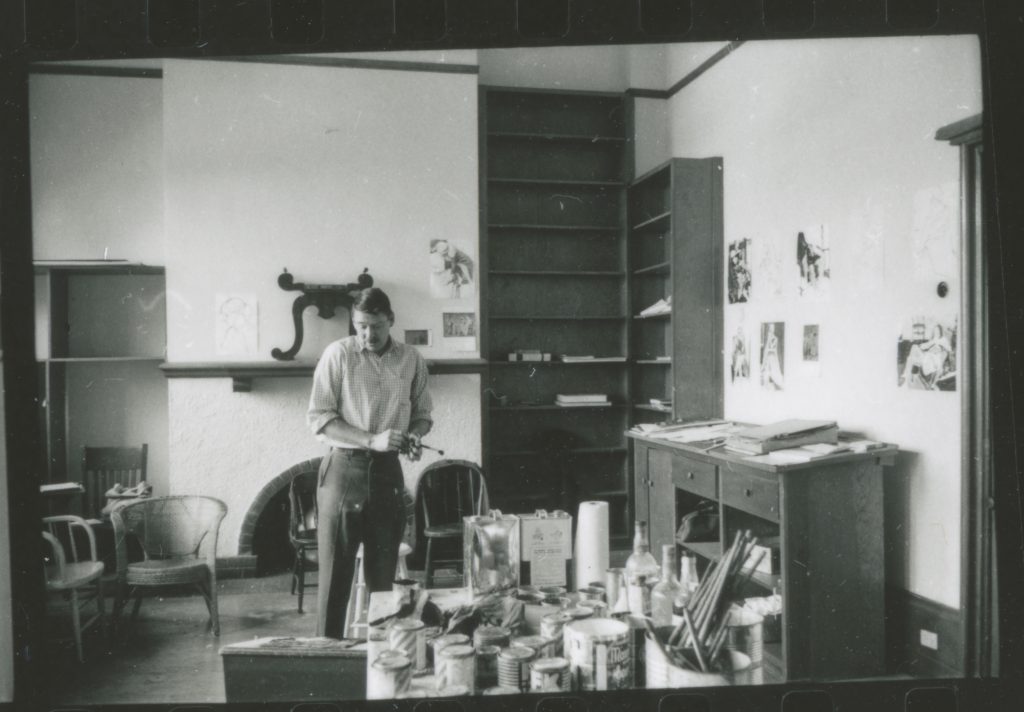

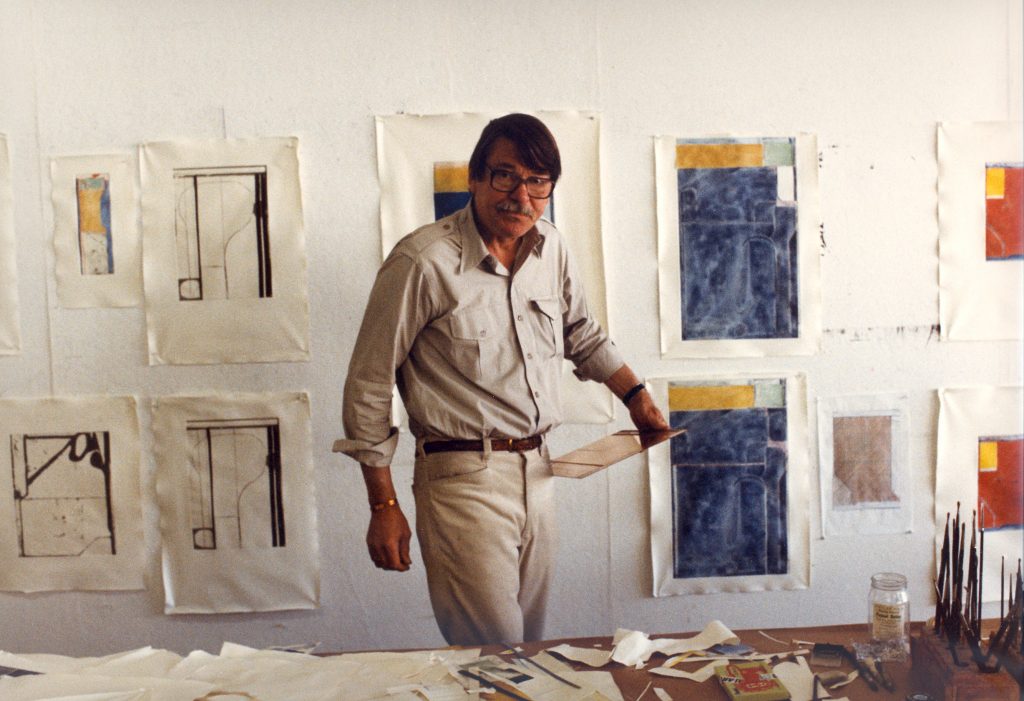

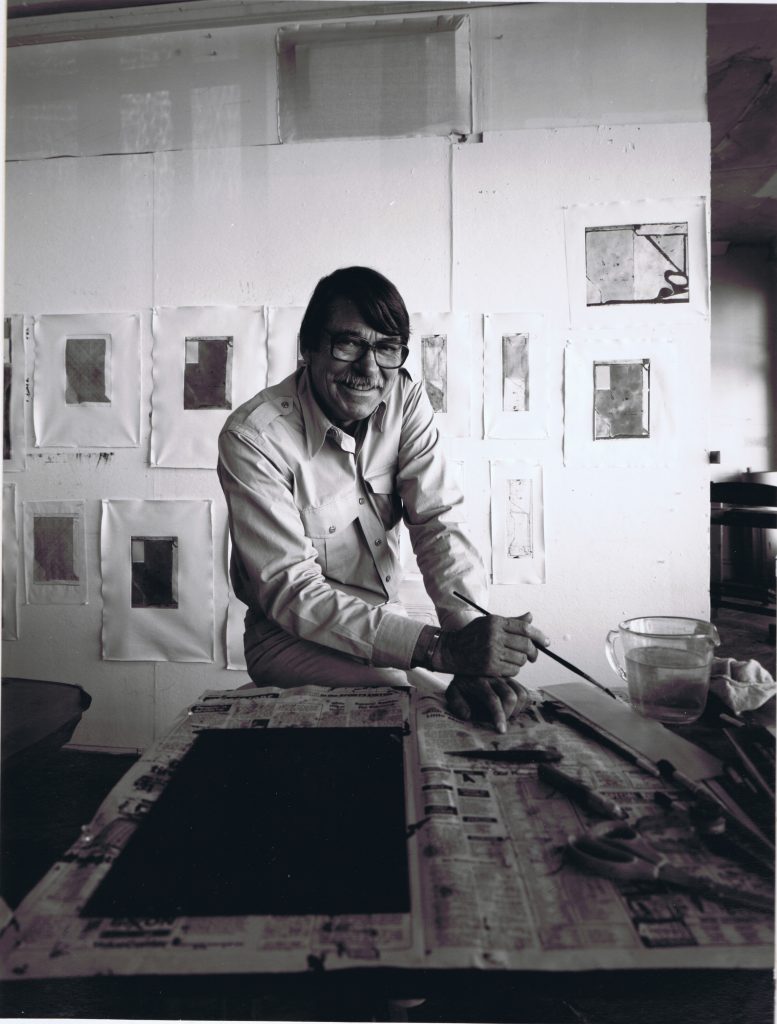

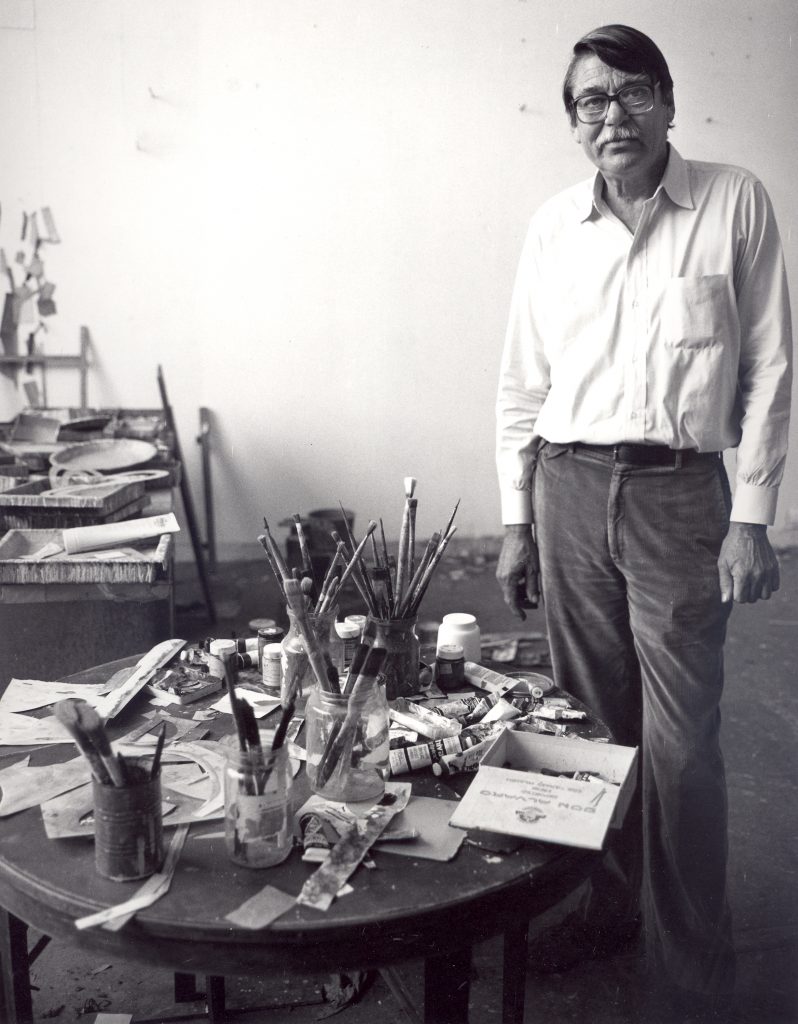

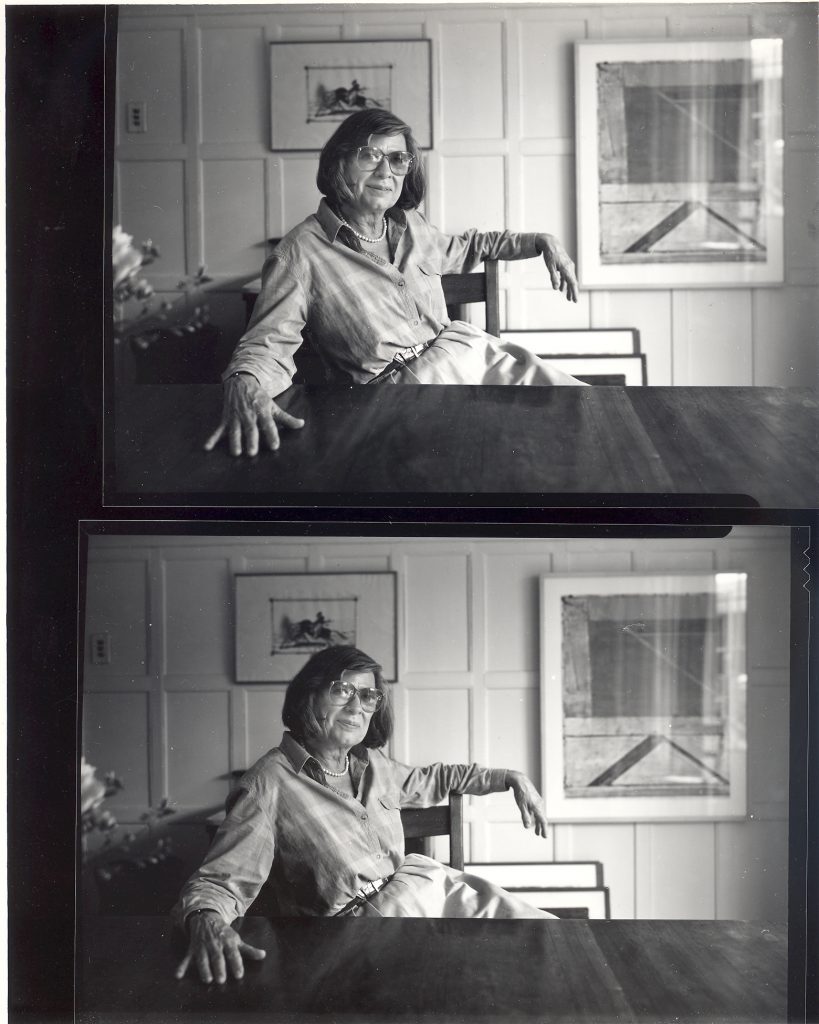

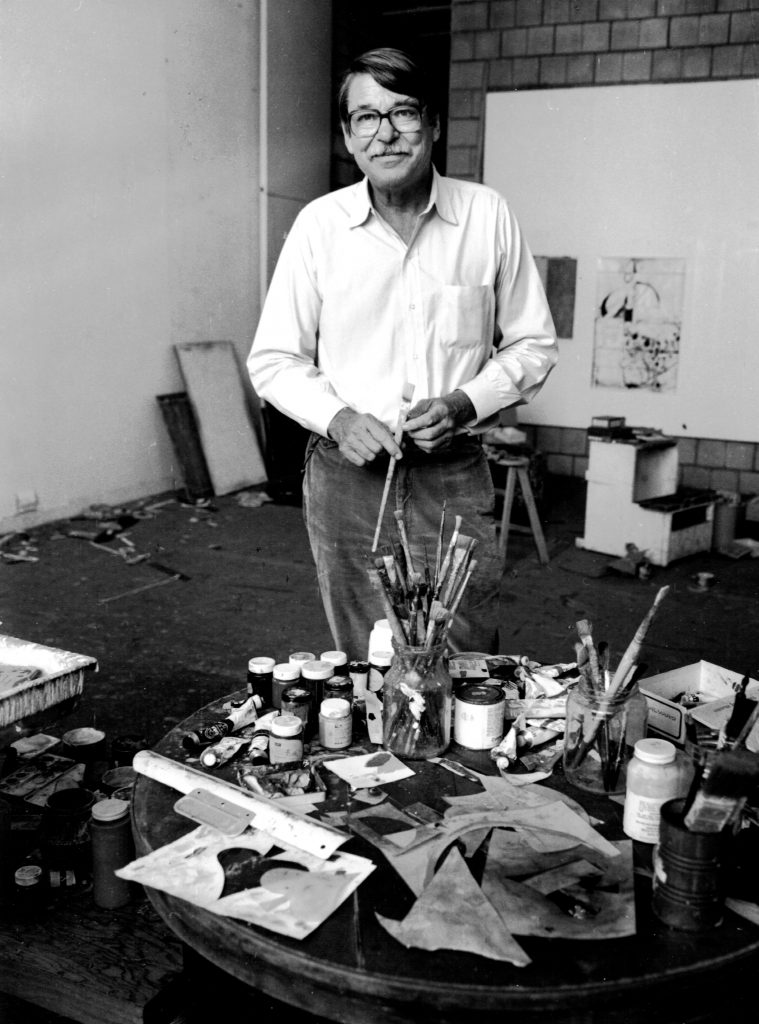

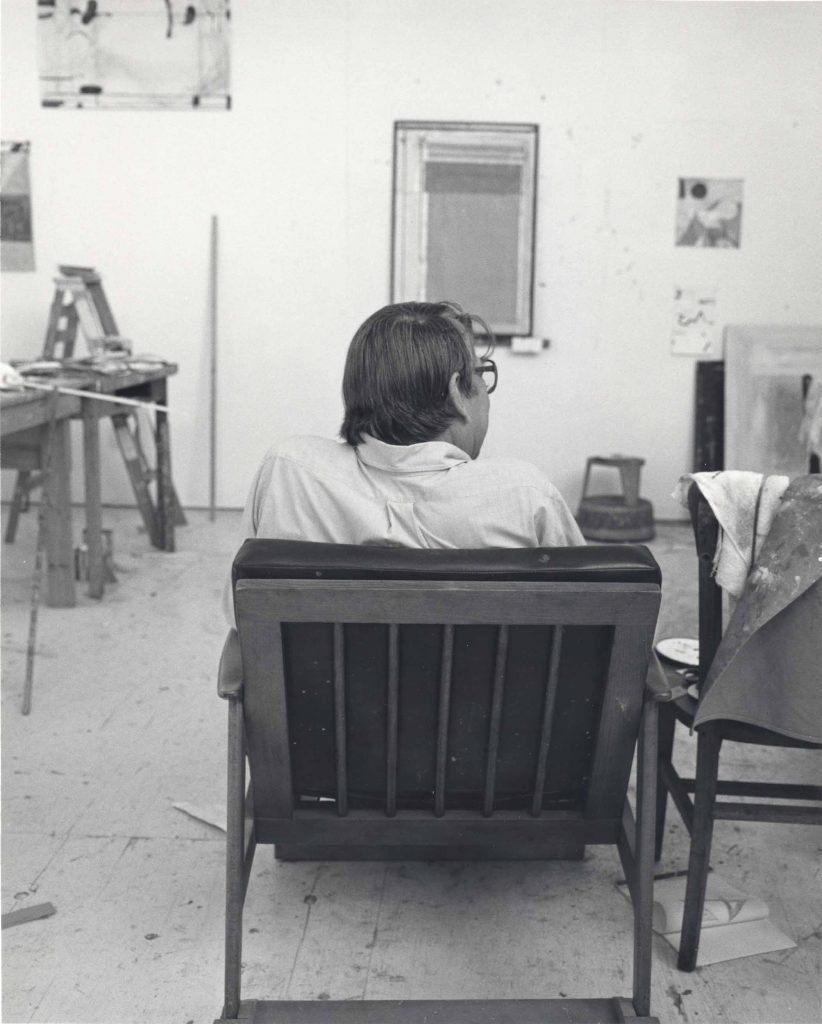

Leo Holub first photographed Richard Diebenkorn in 1963 at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California. At the time Diebenkorn was the university’s first artist in residence, living in Palo Alto for the 1963 to ’64 academic year and working in a studio on campus through a new program established in 1960. Holub worked in Stanford’s planning department and was assigned to photograph Diebenkorn at work in his studio for documentation purposes. A trained artist himself and a friend of Ansel Adams, Holub went on to found the Stanford photography program in 1969. He is most well known for his decade-long project visually documenting more than 110 artists in their studios, an effort commissioned by prominent San Francisco Bay Area collectors and patrons Hunk and Moo Anderson. In 1963 Holub was taking photographs of students around campus, and on one fateful day met Richard Diebenkorn in his on-campus studio where Holub took some of the most iconic photographs of the artist in our collection. Holub would go on to become the professional photographer with whom Diebenkorn worked most closely throughout his career.

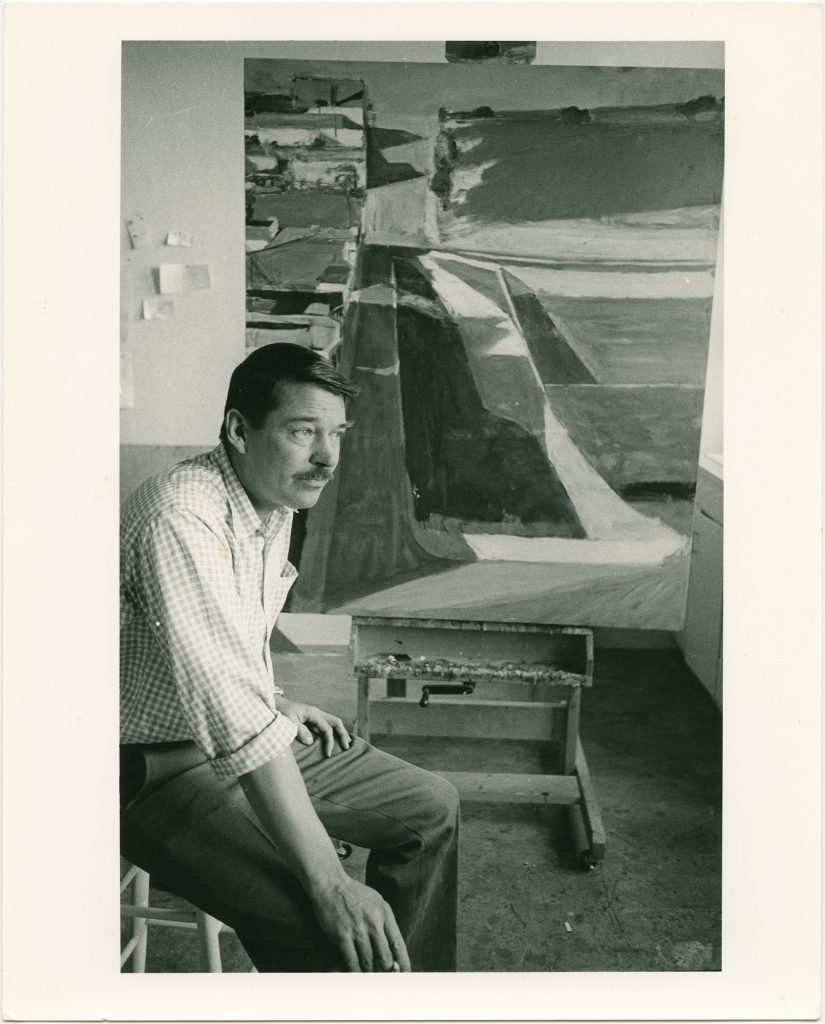

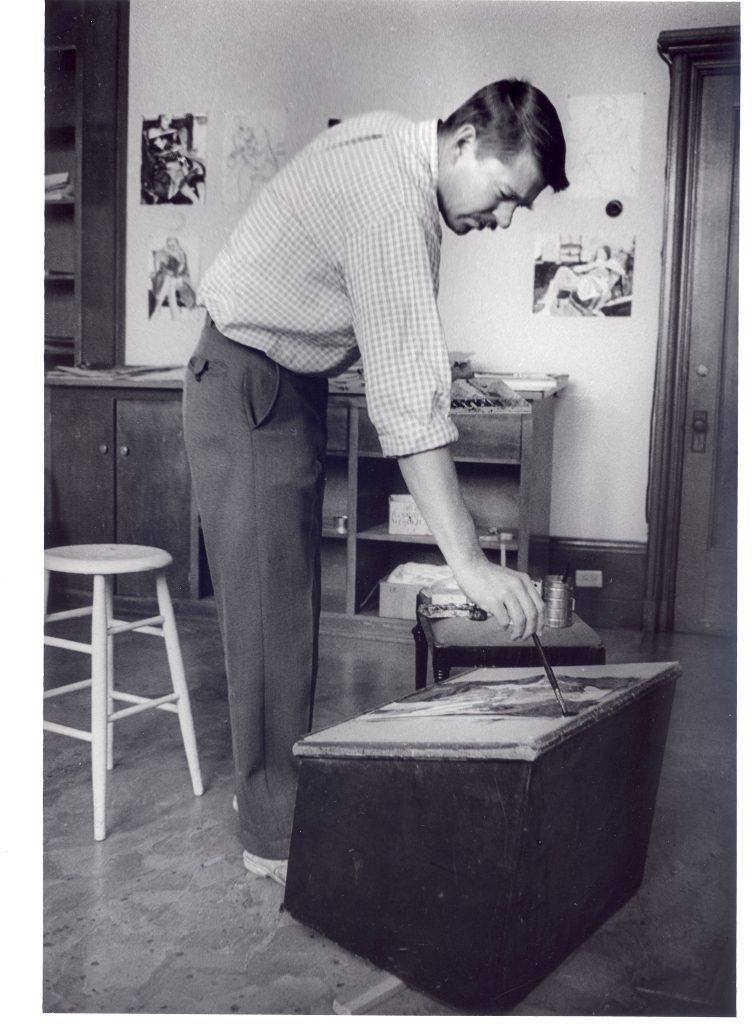

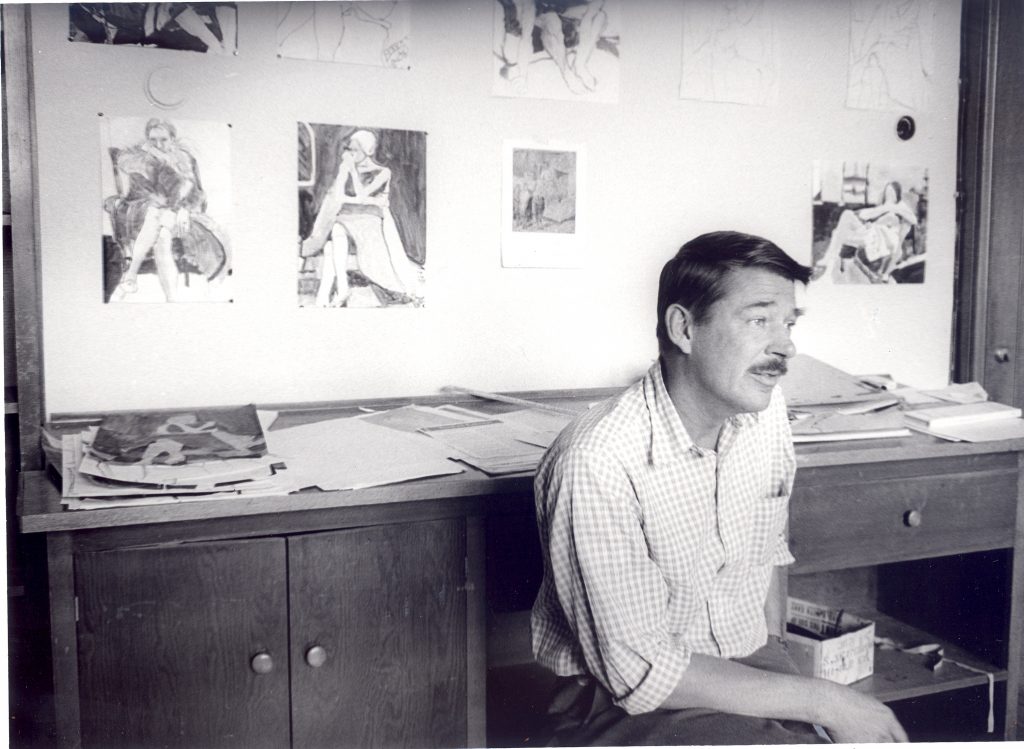

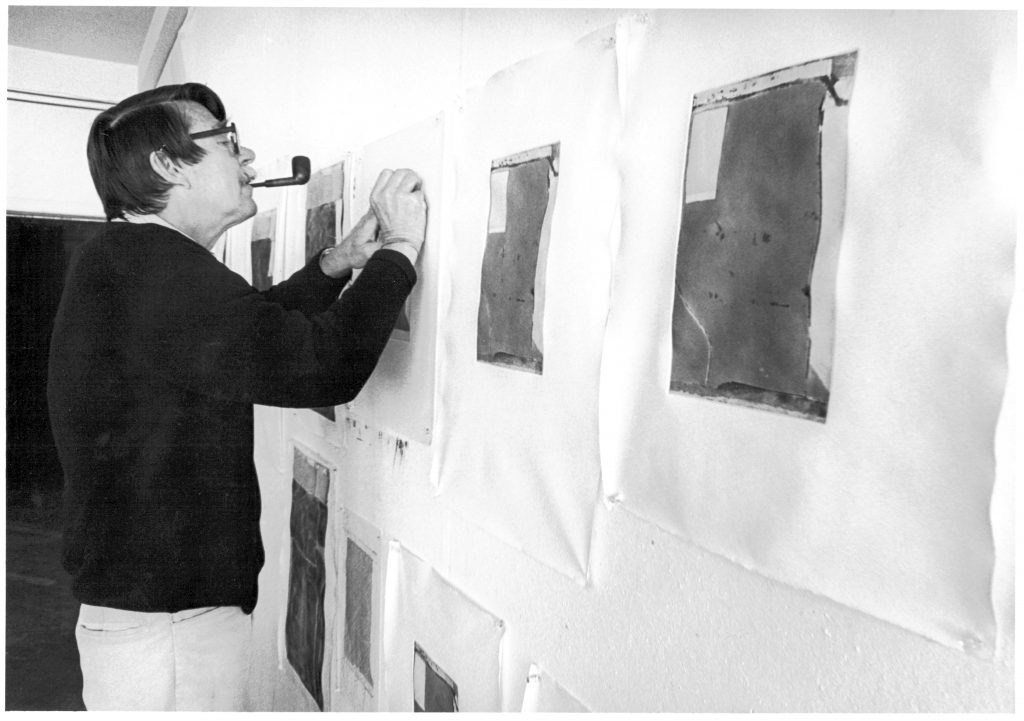

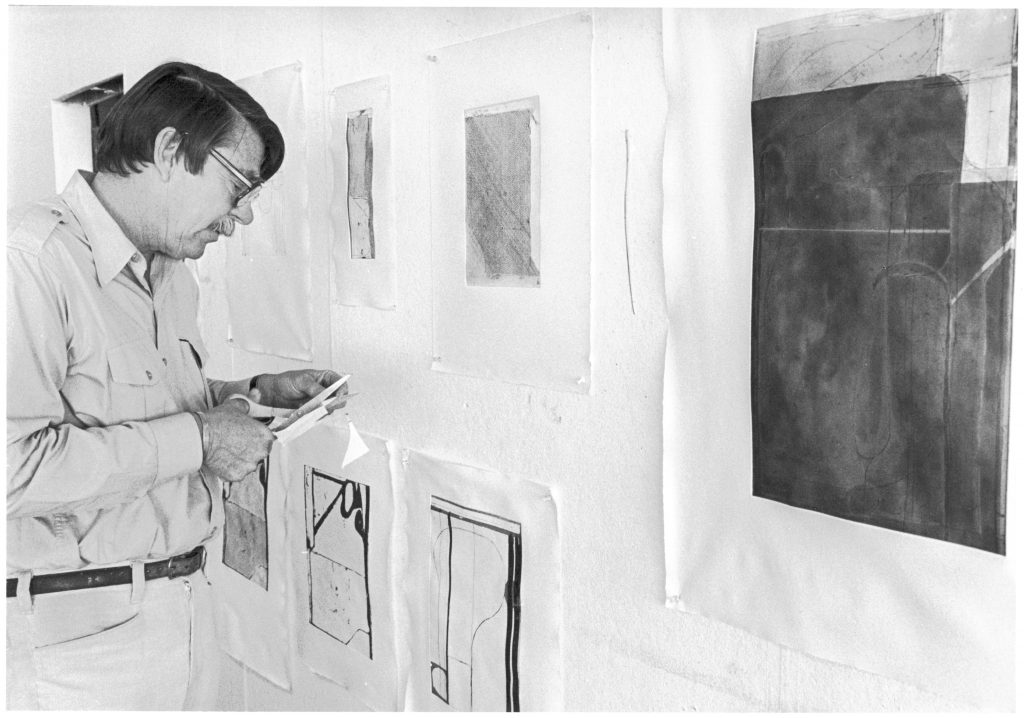

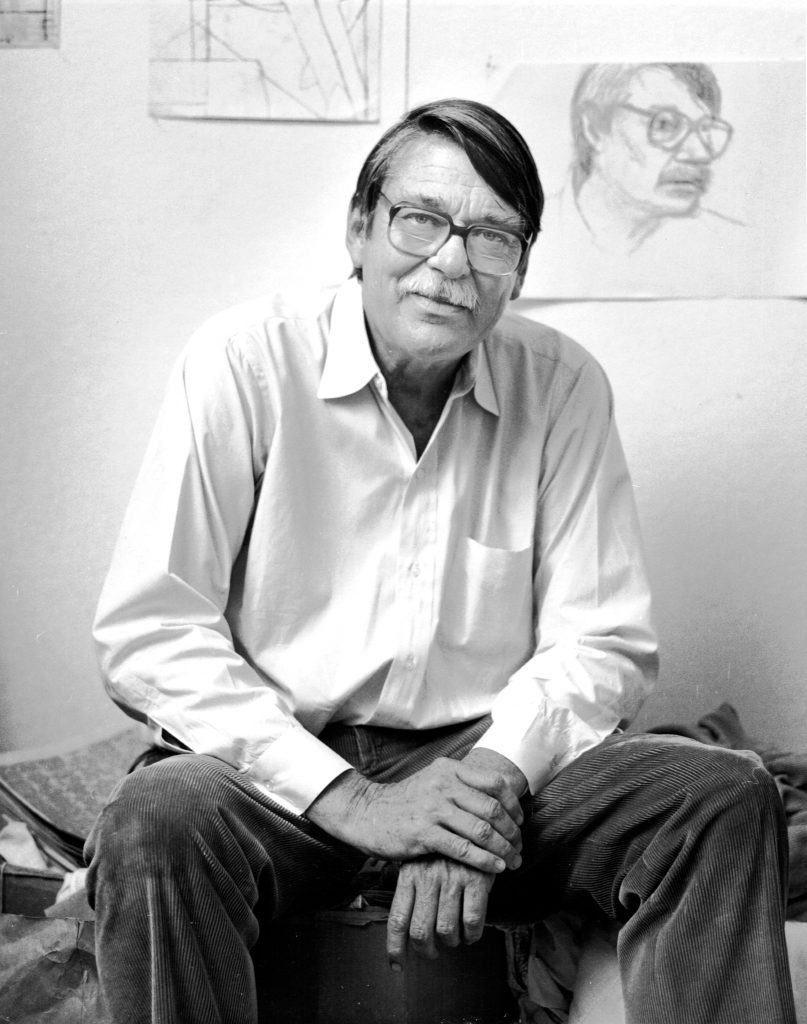

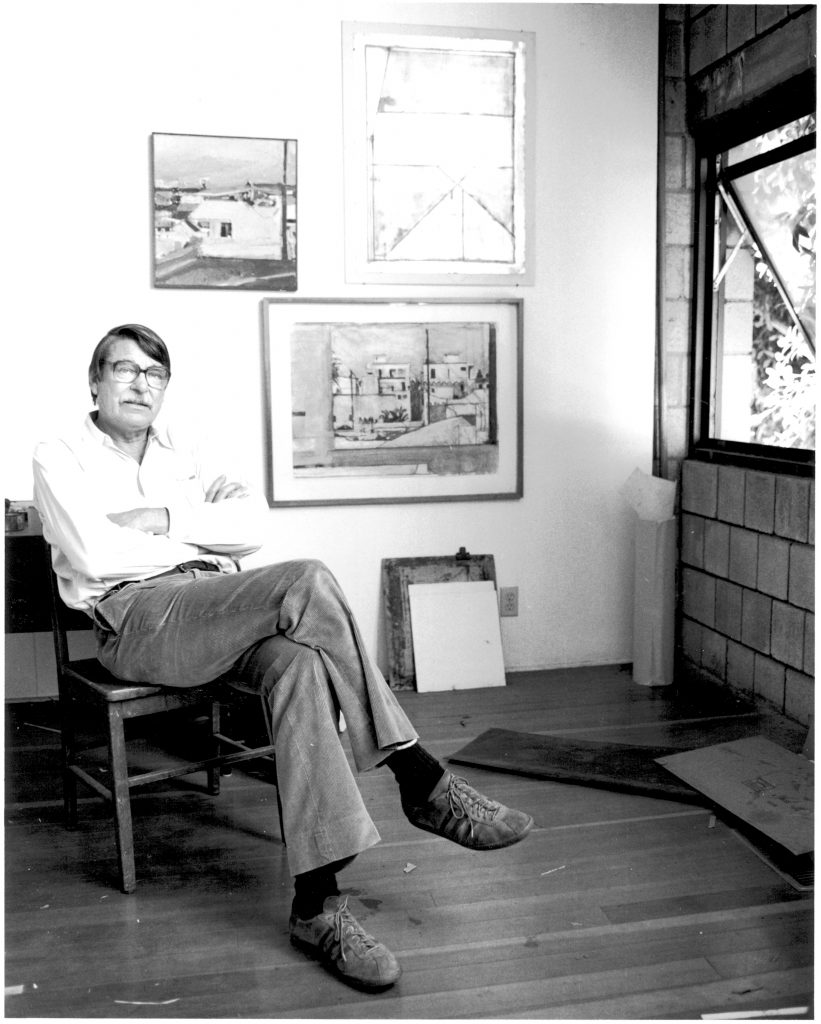

At the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation we have observed that the images most frequently requested for research and reproduction are the photographs in the artist’s archive by Leo Holub. These photographs of Diebenkorn are striking in their beauty and in the rare calm with which the artist beckons us, through the camera lens and into his studio. Diebenkorn is at once cordial and inviting but remains relaxed enough to appear at work. When he meets Holub’s gaze, or when Holub captures him moving throughout his space, Diebenkorn looks as if he is really thinking about his next mark, not about the stranger in his studio. Holub catches the artist looking almost proud of his creations.

The documentation assignment of 1963 not only yielded Holub’s captures of Diebenkorn at a particular moment in his career but also clearly show Holub and Diebenkorn finding a groove. The photographs show an artist at ease. “We hit it off fine,” Holub would later say of the visit which was encouraged at the insistence of Lorenz Eitner, then head of the Stanford Art Department.

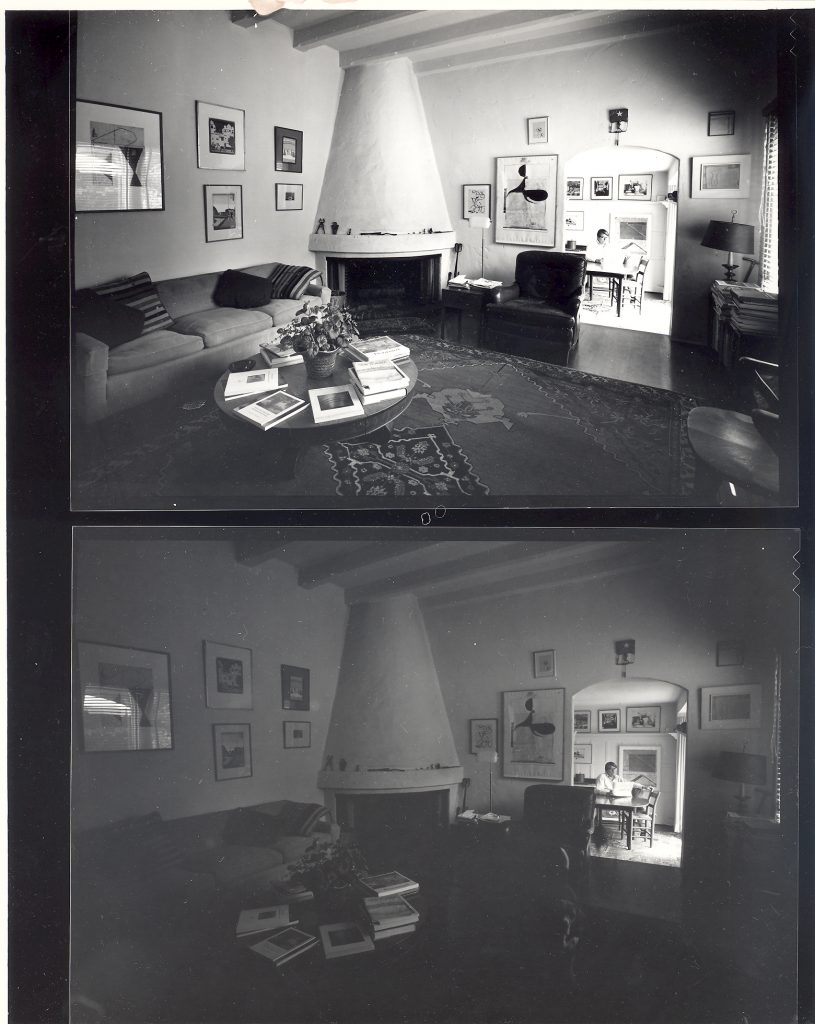

Over the next thirty years Holub would photograph Diebenkorn on three more occasions, each time straddling the artist both at work and in his domestic environment. His lens did not focus only on the large paintings, but also on the drawings in progress—pinned to the walls, framed and hung behind him—and on the tables covered in materials. Diebenkorn often looked decisively into the camera, artist to artist. Something about Holub’s presence put Diebenkorn at ease: Diebenkorn talking, Diebenkorn pointing, Diebenkorn animated, bringing out a canvas from the racks, pointing at a specific work, pinning a print to the wall. Holub captured Diebenkorn both at rest and in action. Somehow Holub managed to photograph the perfect portrait, while not asking for a portrait, and maybe this is what made all of the difference.

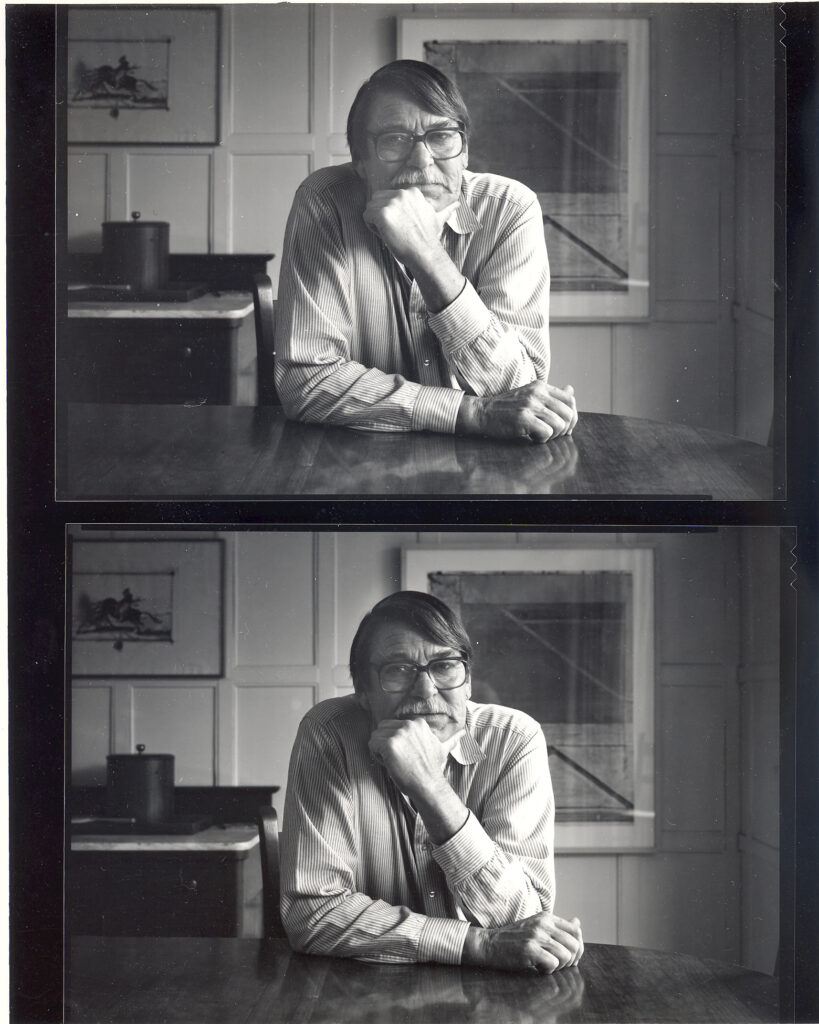

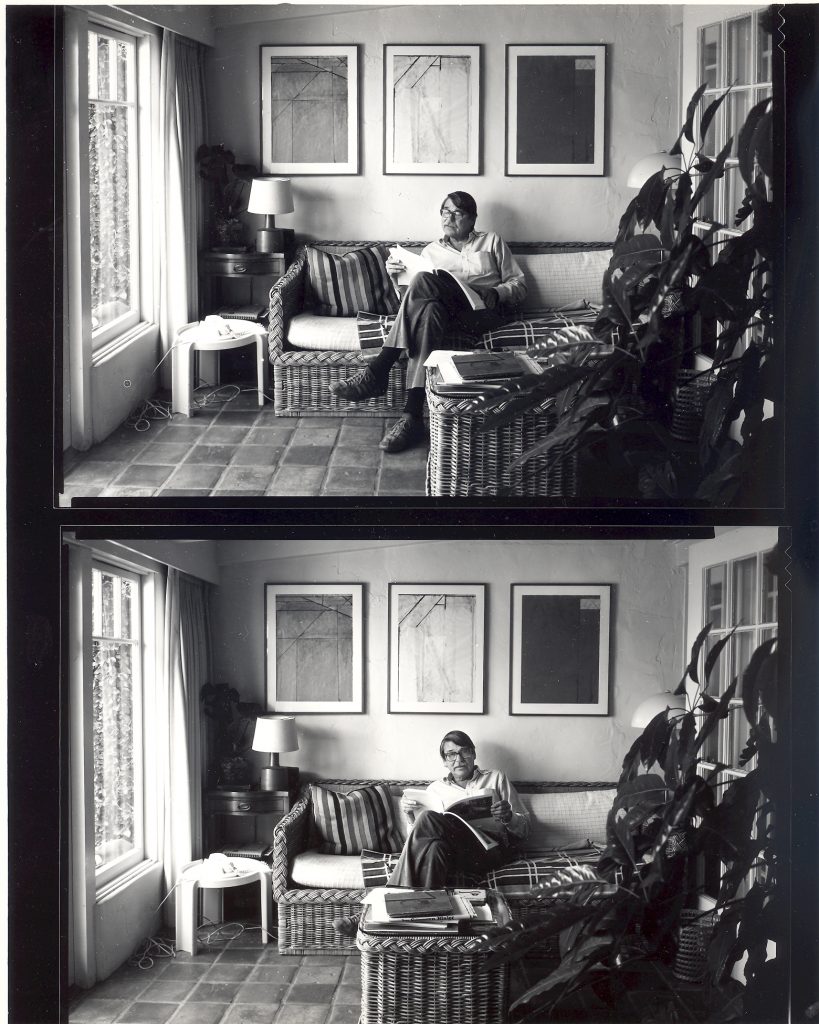

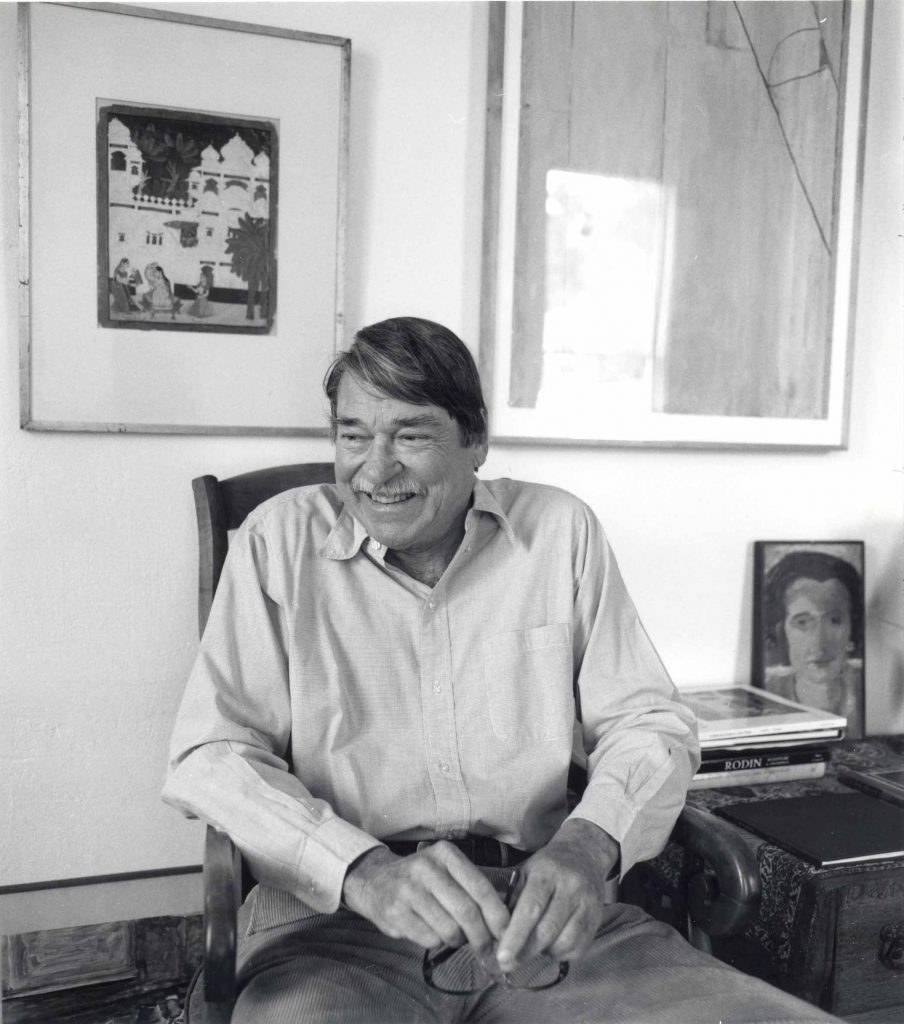

Holub last photographed Diebenkorn shortly before the artist passed away in 1993, a mere month before his 70th birthday. On a visit to see Diebenkorn and his wife, Phyllis, in Healdsburg, Holub took photographs which reveal the hard truth that the artist would be leaving pieces both unrealized and unfinished. The photographer captured not only the loss of the artist but the humanity of a life at its close, revealing the deep strength and perseverance required to face death with bravery and grace. Holub looks tenderly at Diebenkorn, while Diebenkorn’s fierce gaze and thoughtful smile pierce us with their universal desire to be seen as full and not as diminished.

If we line up the photographs from 1963, 1980, 1984 and 1993, we can see the two artists creating a pattern together, and the compositions fall into a familiar flow. Even with his illness weakening his physical form, Diebenkorn connected with Holub through the lens with the same candor. After Diebenkorn’s death, Holub wrote, “…words describing RD I have gathered from various media articles ‘soft-spoken, gentle, sensitive, quiet, modest, self-confident, thoughtful, gifted, serious, professional, intelligent, unpretentious, approachable…’ I validate this list and add the adjective generous…”

And generous was Leo Holub as well. With Diebenkorn’s passing, Holub granted Diebenkorn’s survivors the rights to use the photographs as they saw fit. Holub’s family has further entrusted the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation to grant permission wisely and wholeheartedly. The portraits of Richard Diebenkorn taken by Leo Holub frequently provide us with the opportunity to publish more than a portrait, but a revealing moment with the artist himself. They are stunning in their clarity and they express a joy in art and art making.

1. Leo Holub, in an oral history interview, 2009, Stanford Digital Repository, Stanford University, Stanford, Calif. © The Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University (accessed on 05/09/2021 https://purl.stanford.edu/dr507qf6765)