As Seen By: Nellie Gilman Fryer, Richard Diebenkorn’s Mother-in-Law

By Daisy Murray Holman

August 25, 2021

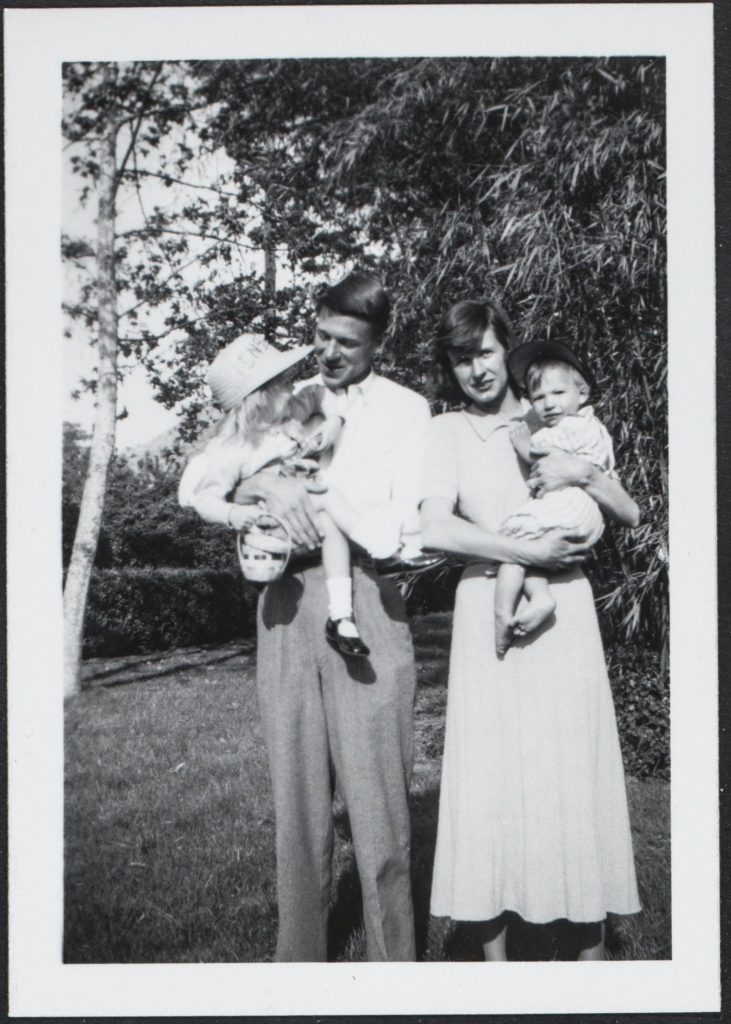

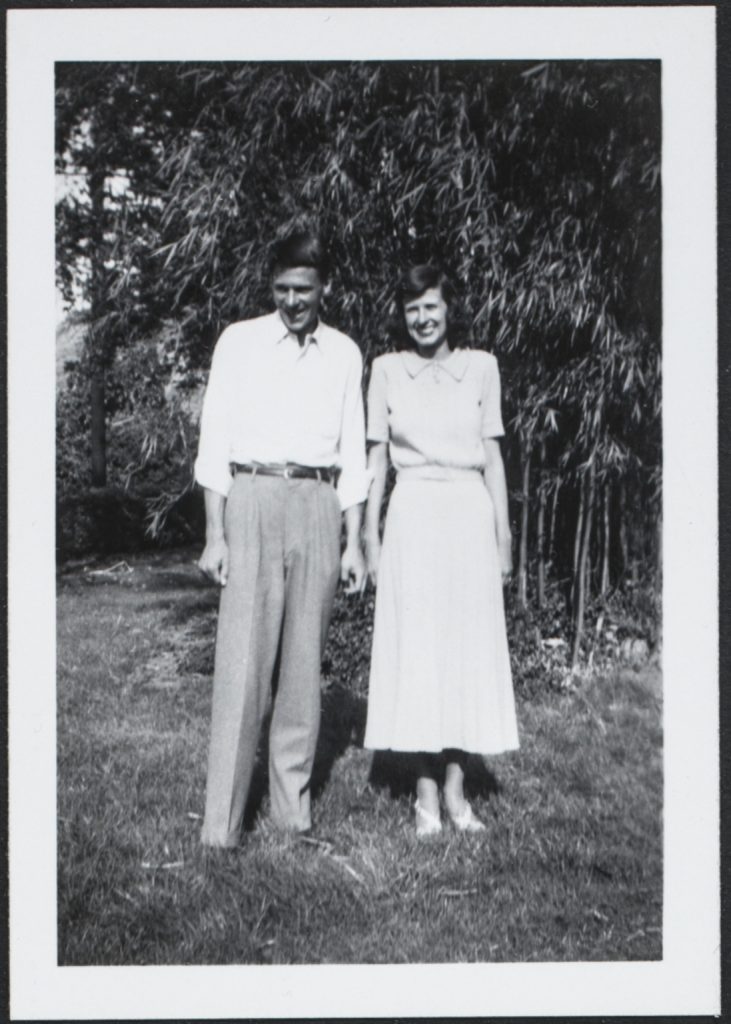

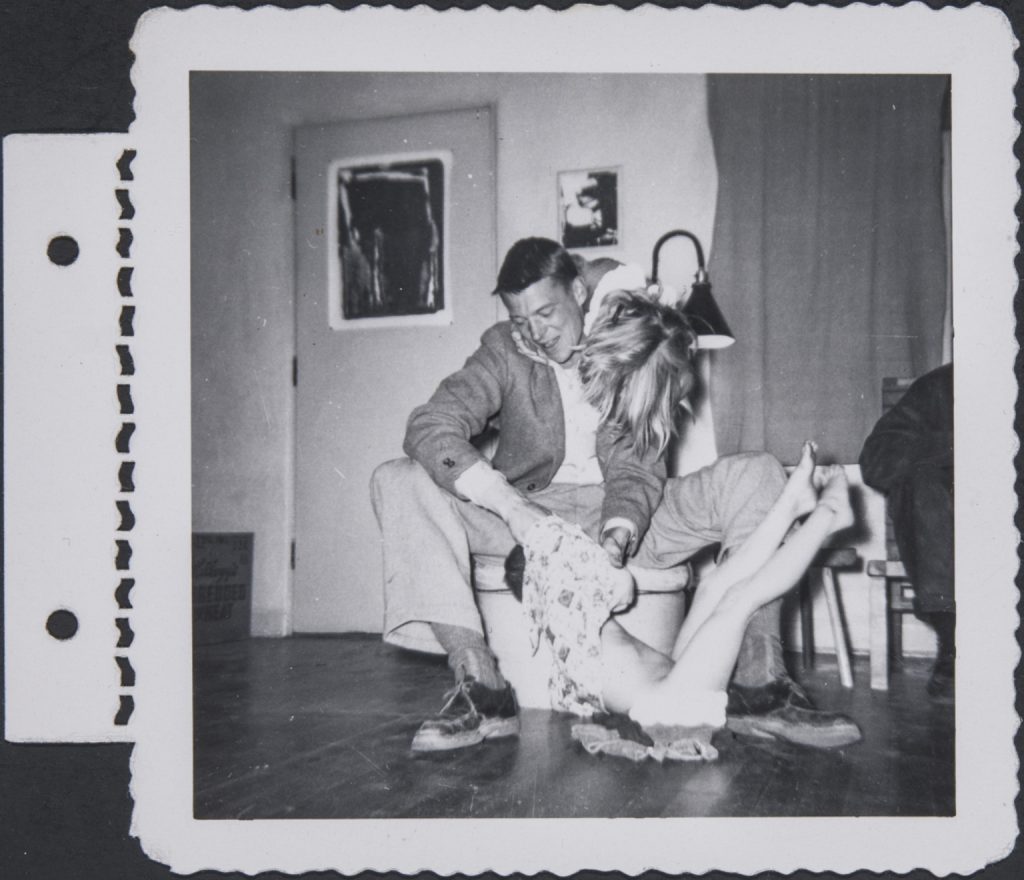

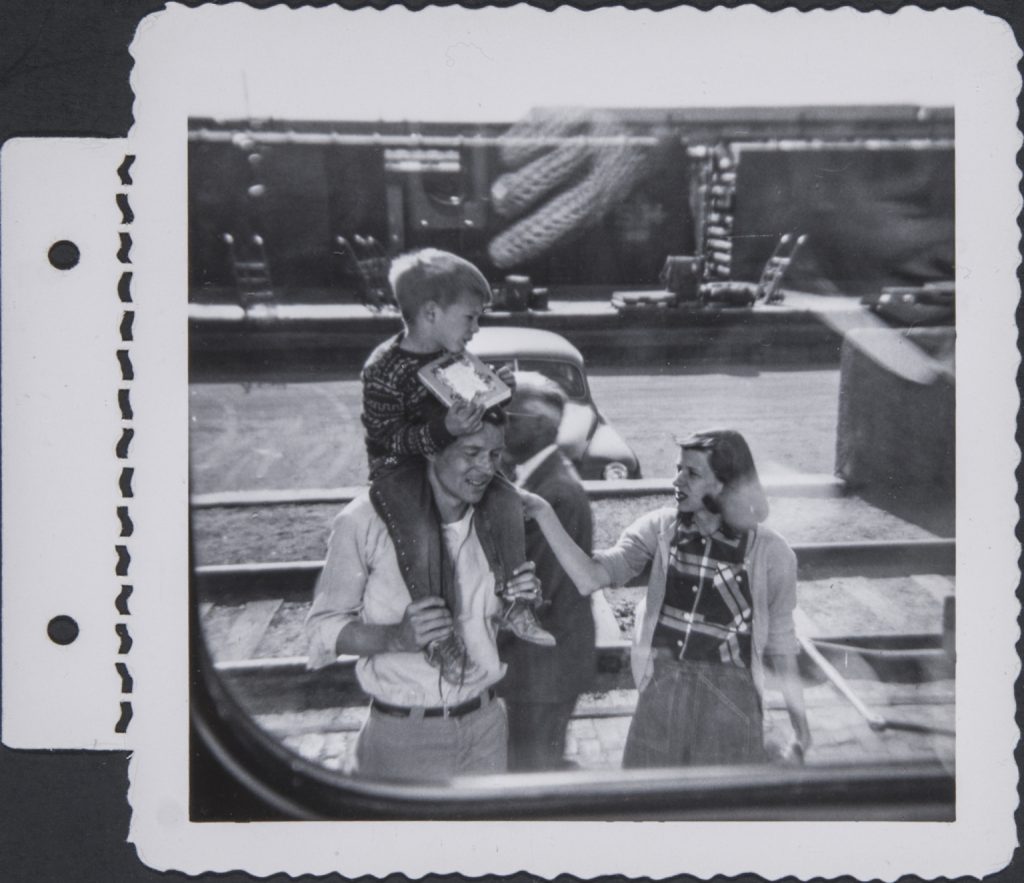

A young couple stands in the bright sun and holds their small children securely in their arms, loose enough so they can still wiggle but tight enough so they will not fall. The father looks into his charge’s eyes with a smile, and the mother looks directly out to the photographer, a knowing look of “last one, Mom; these kids need to run.” The parents stand side by side, their arms touching, smiles ablaze, giddy. A child flips over a swing tied to a tree branch, feet akimbo. A father, still in his coat and dusty shoes, wrestles one child into pajamas while the other climbs over his shoulder.

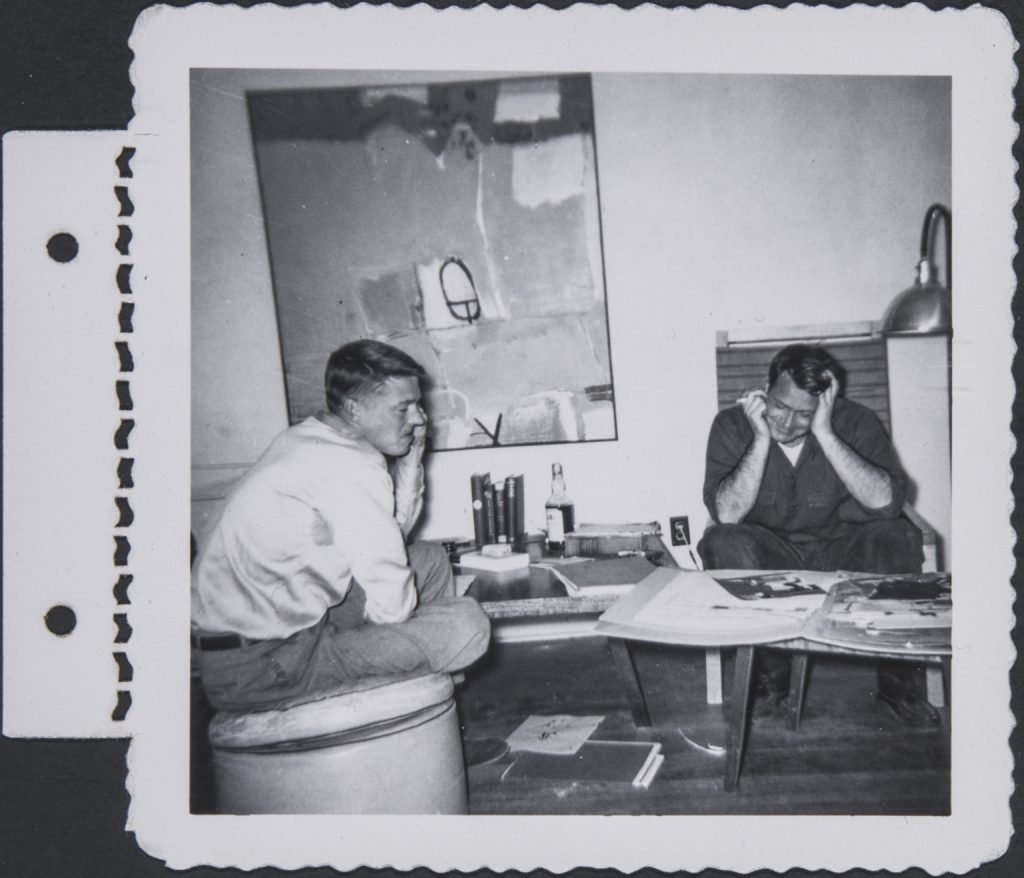

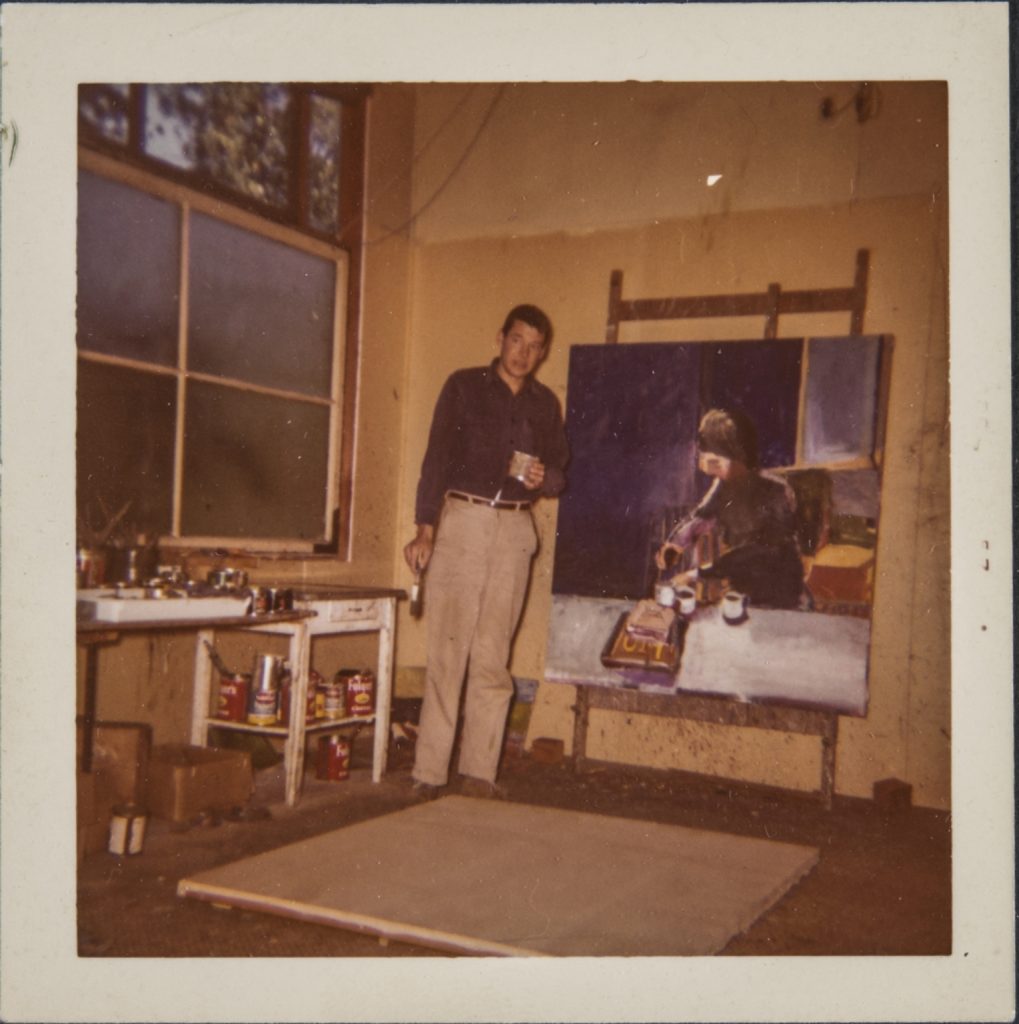

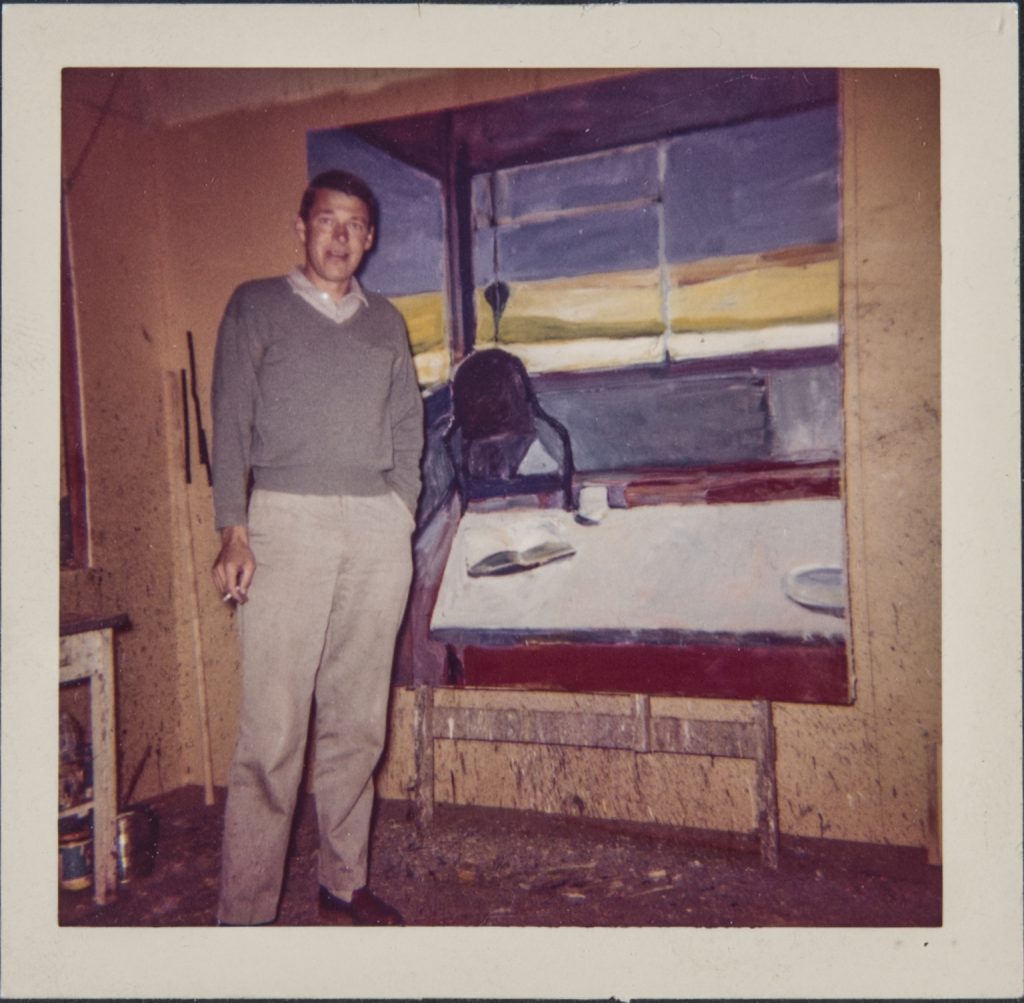

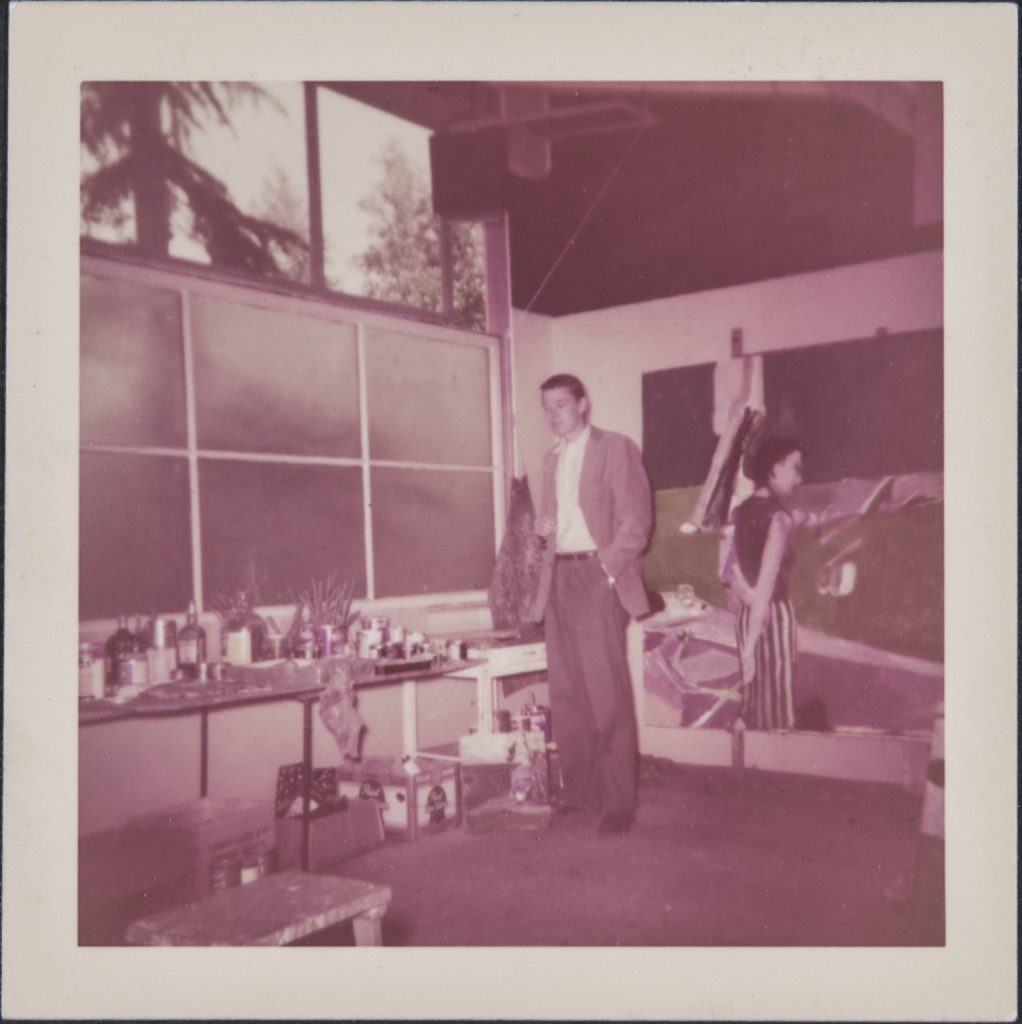

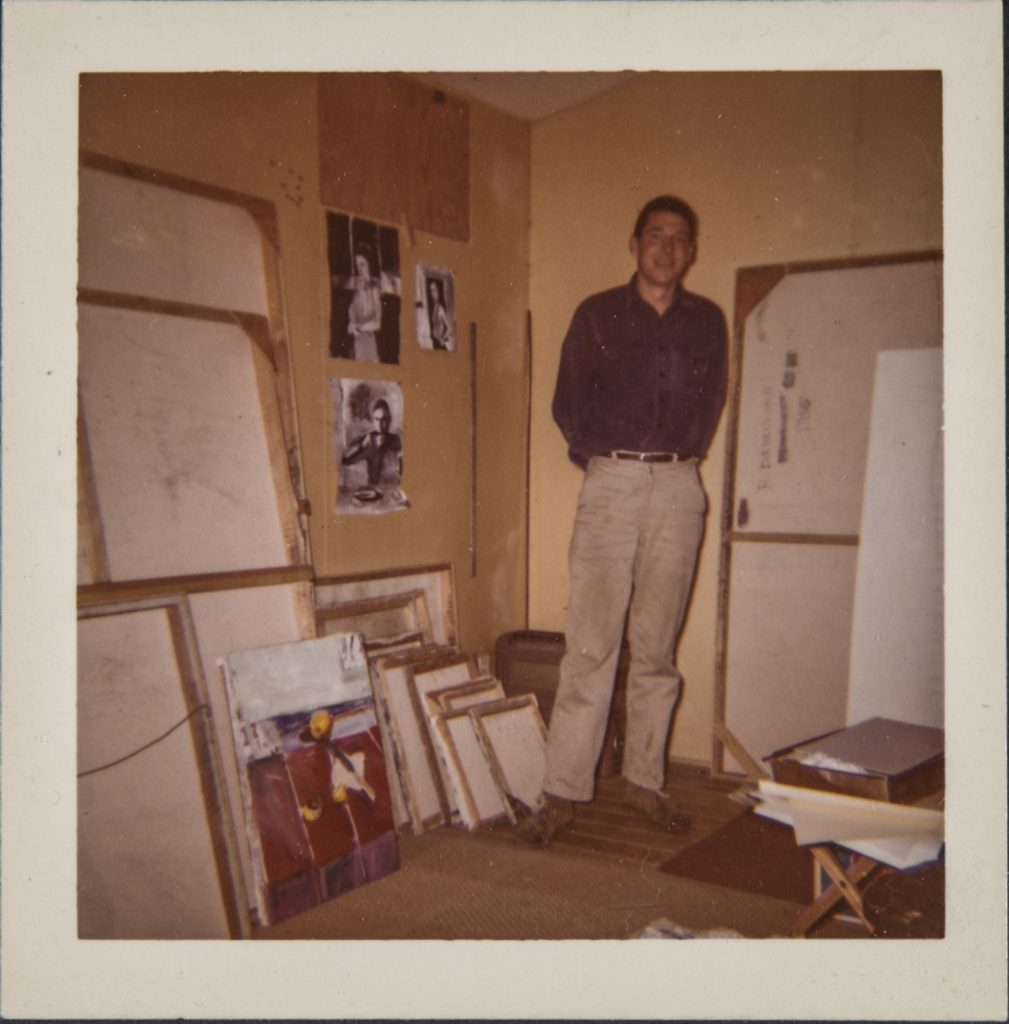

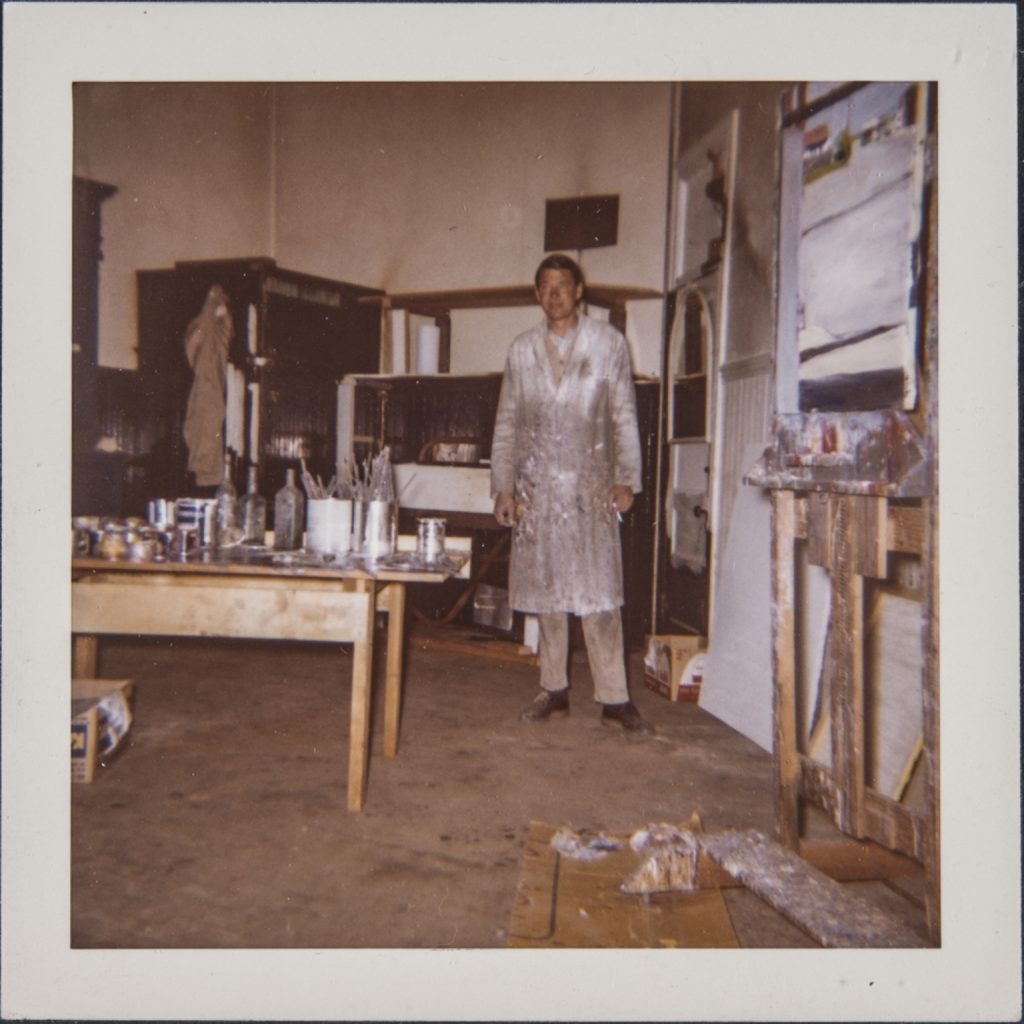

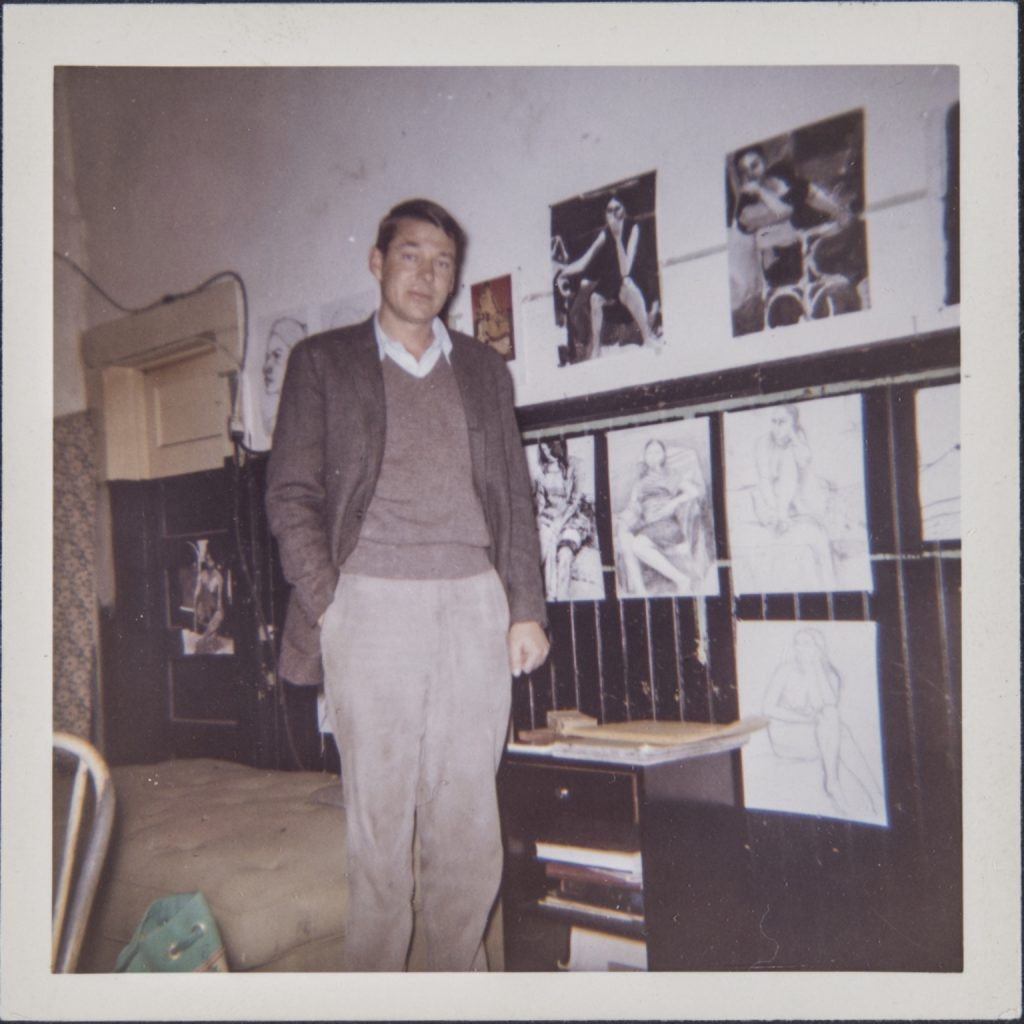

The same father sits with another man in front of a large painting; the other man smiles while looking down at a drawing. The father stands in the corner of an art studio, again with a large painting behind him. The image repeats itself. Looking through the stack of photographs the pose becomes familiar: the man in front of various paintings that usually appear complete, a sheepish smile on his face, maybe holding a cigarette or with his hands in his pockets, casual and yet clearly standing because it was requested of him. He is not looking at the photographer with annoyance, but with patience and respect. These candid photographs of Richard Diebenkorn were taken by his wife’s mother, Nellie Gilman Fryer, and emerge as a distinct body of images in the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation’s series of personal photographs. Fryer’s albums stand out not only in volume but in their clear portrayal of Richard Diebenkorn as both a father and an artist.

Nellie Gilman Fryer was a devoted mother to Phyllis, Diebenkorn’s wife, raising her only child as a widow in interwar California. Fryer was deeply ingrained in her daughter’s life. She watched the Diebenkorn children, Gretchen and Christopher, for stretches of time at her home in Spadra, California, while Richard and Phyllis took care of the practical aspects that came with moving a young family around the United States. Fryer visited them wherever they lived (except for Woodstock, New York) and in some cases provided the only photographic evidence of the young family’s life in certain locations. Fryer, who passed away in 1974, was generous with her time, support, and love. Phyllis and Gretchen held her in the utmost regard, and she is still sorely missed by her family.

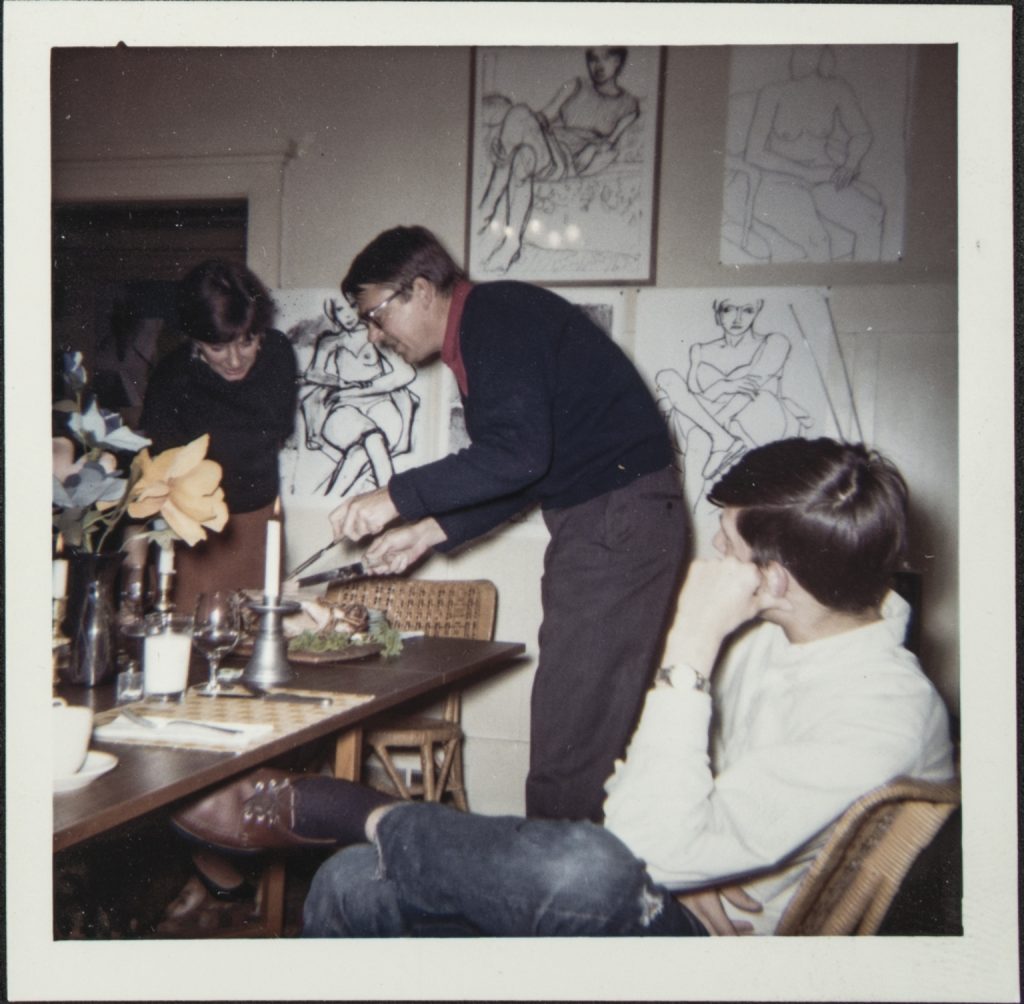

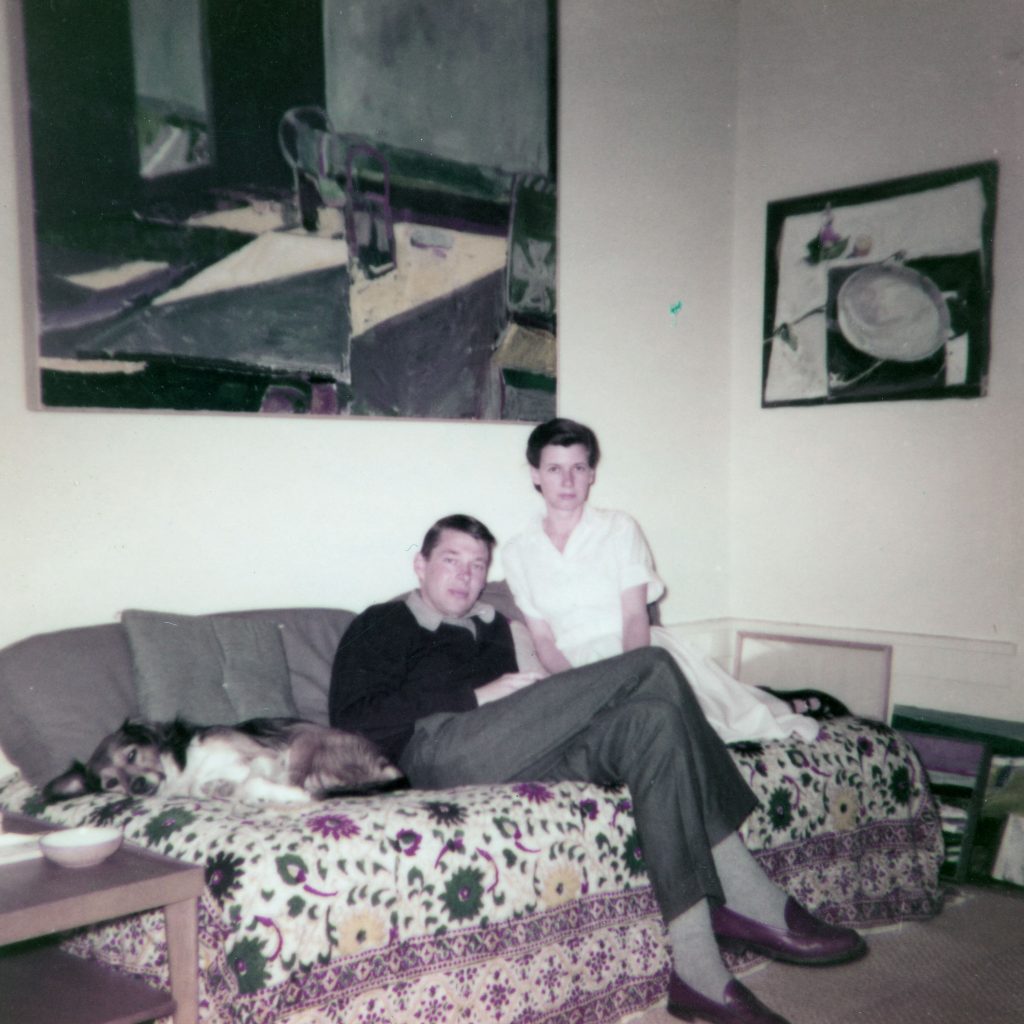

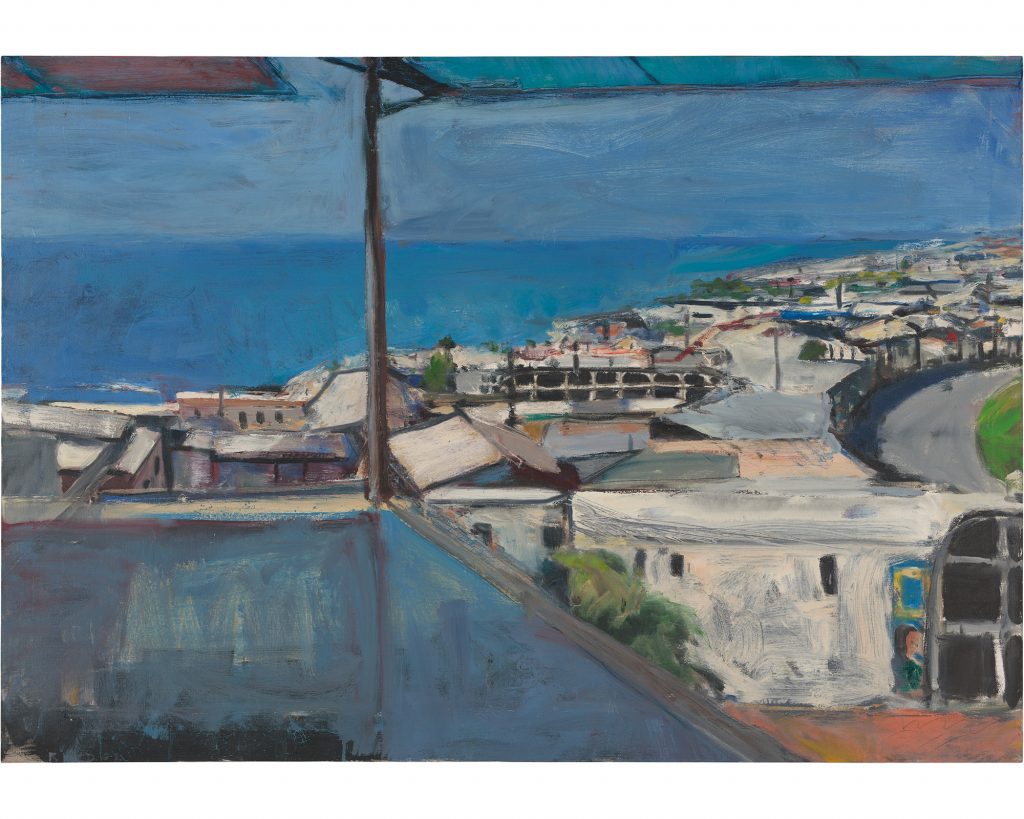

We can see the intimate bond between Phyllis and her mother through the hundreds of, at times daily, letters between the two. Fryer was also a deliberate and active amateur photographer who never visited without her camera. At first glance the numerous photographs of her grandchildren playing with kittens or attending a birthday party may overwhelm, but a closer look reveals the significance of her documentation: on the walls is a rotating selection of paintings and drawings by Diebenkorn, some remaining and some moving from the house to the studio and then out into the world. Paying close attention to what hangs behind Fryer’s primary subject, her family, allows us to see what most interested Diebenkorn at the moment the photograph was taken. We are lucky she saved everything and that in turn Phyllis did as well—including negatives and numerous duplicate photographs—for Fryer’s pictures not only tell the story of the family’s life, they also provide scholars and historians with details about Diebenkorn’s art and painting methods.

The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives contain more photographs by Nellie Gilman Fryer than any other individual. She was persistent in documenting the completion of major paintings by an artist well known for his privacy. Few professional photographers were allowed into Diebenkorn’s studio, even fewer into his home. Fryer’s detailed documentation of the artist in his studio and home illuminates a key element of his practice. For Diebenkorn there was no line between work and life. His paintings traveled with him from the studio walls to the living or dining room, and the changing display allows us to see not only the work in progress but also the ever present nature of his art for his family. In 1963 he wrote a letter to his New York art dealer Elinor Poindexter, explaining this working process: “At worst what can happen when individual paintings, especially key works, slip out prematurely, is that I must start from scratch on each new painting. I can only blame myself for making exceptions to the way I know is right which is to hold tight to all work until a kind of realization for the whole period is made.”1

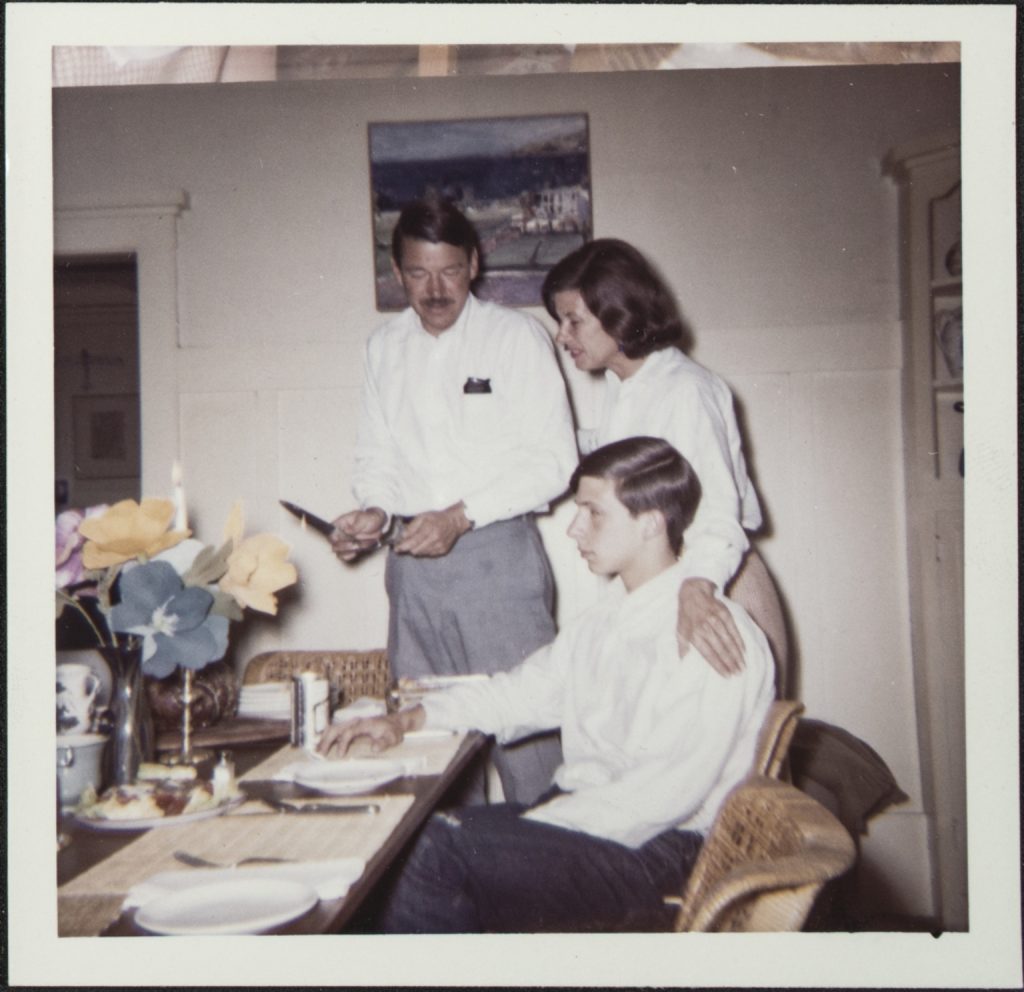

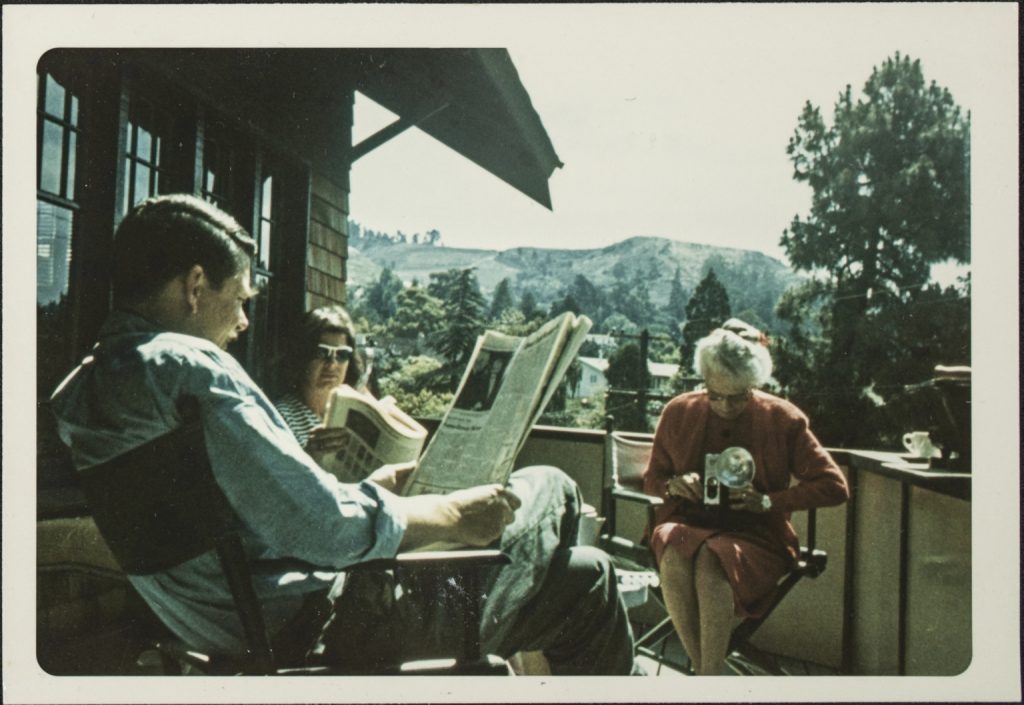

Nellie Gilman Fryer preserved some key aspects of the artist’s development of a composition over time. She also captured the habits and roles of Diebenkorn family members. Her photographs show the painting Santa Cruz I (1962) with a striped and scalloped awning spanning the left side of the work. The artist later painted over these rounded edges and extended the awning across the entire top edge. In the painting Sleeping Woman (1961) the woman slept on a chair with striped cushions underneath an open window in a primarily red environment. The finished painting shows the woman leaning her head and arms over a couch above which a large mirror hangs, the only constants between the two states being the shape of the woman and the drawing pinned to the wall. In her still pictures of the family life, Fryer documented Diebenkorn as the one to traditionally carve the roast during holiday meals. The family enjoyed sitting on their patio with coffee and newspapers. Phyllis enjoyed soaking up the sun, they both loved to read, and the two shared a palpable and endearing physical closeness.

Fryer’s photographs show the vital importance of the family documentarian. In 2010, four years before the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives were established and the staff was deep in the research for the Richard Diebenkorn: The Catalogue Raisonné, a small envelope of Fryer’s photographs accumulated by Phyllis Diebenkorn was brought into the office for scanning. The group hinted at the deep resource this personal collection of photographs and letters would become for the writing of the chronology in the artist’s catalogue raisonné and for research by numerous curators and scholars over the next decades. Fryer’s photographs motivated us to look further, to dig a bit deeper into the closets, and to work ardently to identify each sliver of artwork captured. The work has been rewarding and undertaken with an entirely clear conscience. As Fryer photographed with permission and honesty, and while her photographs are at times blurry and the color is not correct, we know her subjects were willing and adoring of the one pressing the shutter.

1. Richard Diebenkorn, letter to Elinor Pondexter, March 18, 1963, Poindexter Gallery records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.