From Folgers to Montecristo: Richard Diebenkorn’s Studio Materials through the eyes of a young artist

By Gabrielle Rivera

August 30, 2022

With famous artists, we often feel like we know them. We have studied their works, sketches, techniques, processes, and more. I have admired Richard Diebenkorn from afar for many years ever since viewing the Matisse/Diebenkorn show at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2017. However, like many, I only thought I knew him as my knowledge of Diebenkorn focused on a small part of his long and dynamic career. This past summer I worked with the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation as their summer intern. Over eight weeks, I was lucky enough to process the studio materials in the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives. Having the opportunity to go through his studio materials, I learned about Diebenkorn in a whole new light. I found four objects particularly fascinating not only from an art historical perspective but also from the perspective of being an artist myself, and I am thrilled to share these never before seen objects with you.1

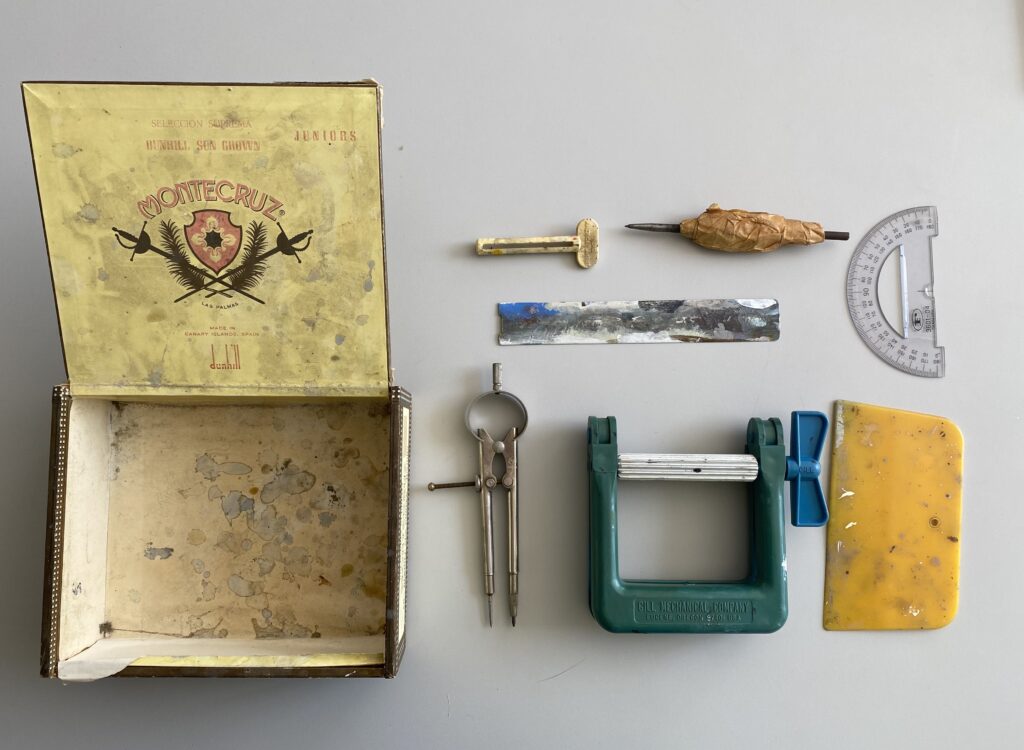

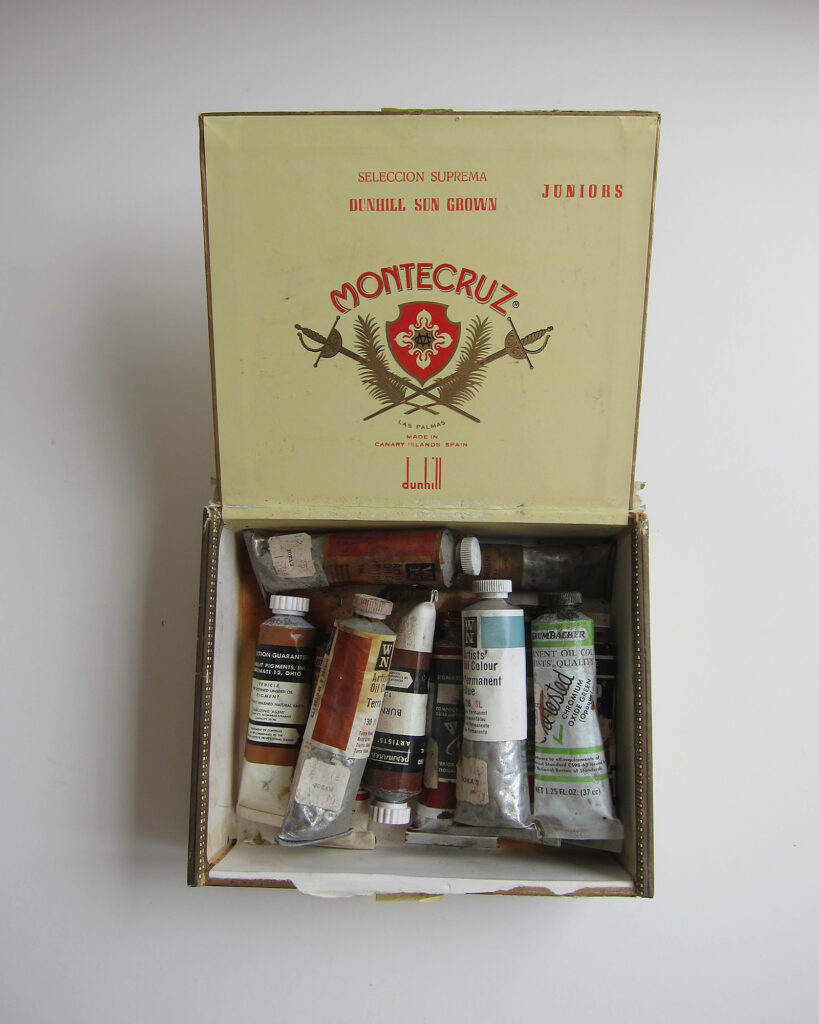

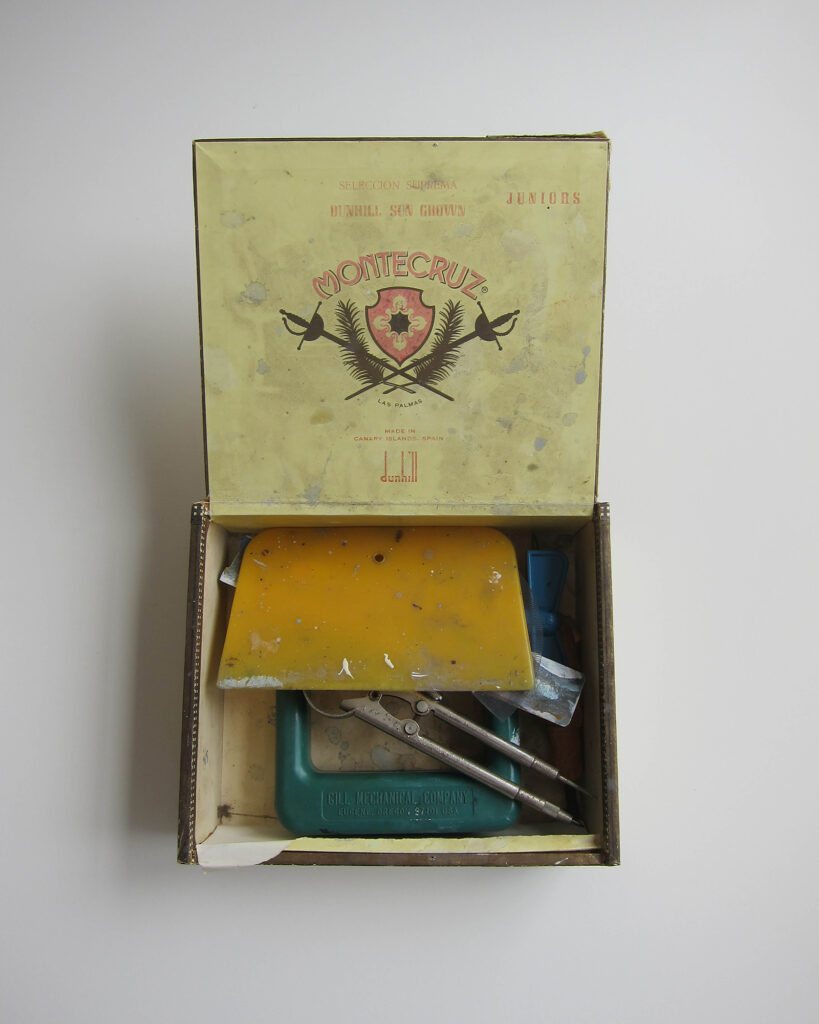

Diebenkorn was a simple man, he was not flashy or arrogant. He lived a quiet life with his wife Phyllis and their children. His own personal oasis was his studio, where he created physical representations of the world as he saw and interpreted it. Writer and critic Dore Ashton once described the Ocean Park paintings as “vectors of human habitation that are his daily California experience,” observing that “For Diebenkorn the entire Ocean Park series consists of a searching out that, when completed, stands, like a good poem, as a concrete analogue of the relations between nature and imagination.”2 Although his work did not always depict a person, his paintings were personal as they captured his own way of seeing the world. In a similar vein, Diebenkorn’s studio and what he brought into it was an extension of himself. He did not seek the most expensive or popular materials: he stuck to what he knew and thought worked well for his uses. In his collection of miscellaneous paints, which include oil, acrylic, tempera, gouache, and watercolor, there are multiple tubes of the same colors, including ultramarine blue, cadmium red, raw umber, cadmium yellow, cobalt blue, Prussian green, and chromium oxide green. These same shades keep popping up across various brands, making it clear he cared little about the paintmaker and more about the color itself. Diebenkorn also often created his own tools out of common household items. An example of this is the small segment of a Venetian blind he used as a straight edge that was found in a box full of paint supplies. However, the true embodiment of Diebenkorn’s do-it-yourself nature was his paint strainer.

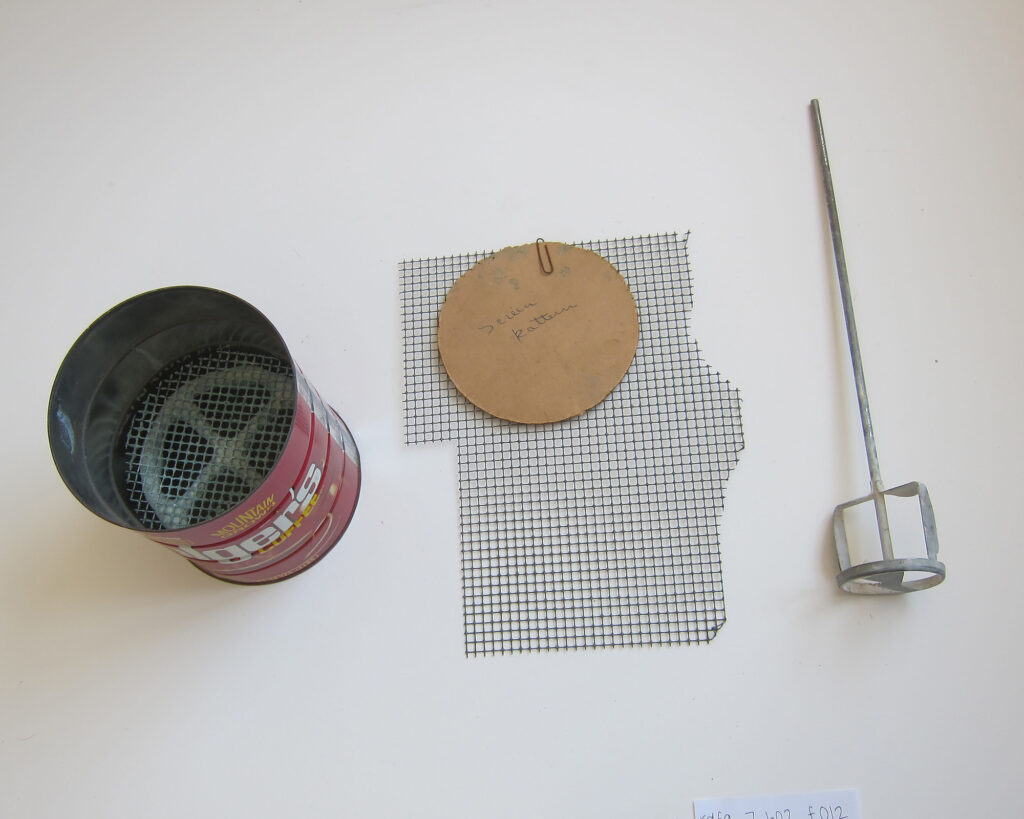

Found amongst his studio materials was a three pound Folgers coffee tin. This item was recycled after its original intended use and repurposed as a makeshift paint strainer. A wire grid cut into the shape of a circle fits perfectly inside the can. Underneath is a circular metal stand with a metal cross in the center and prongs coming out below the outer rim, allowing it to stand on its own. Both of these objects are covered in copious paint residue from heavy use. In the same box as the paint strainer was a mixing paddle attachment for a drill and a circular cardboard cutout labeled “Screen pattern” paperclipped to a larger square piece of a metal wire grid. It is assumed that Diebenkorn used the cardboard pattern to cut out a replacement grid to place inside the tin whenever the strainer stopped functioning to his liking. This paint strainer was a contraption all on its own and exemplifies the nature of simplicity in which the artist surrounded himself.

Diebenkorn’s resourcefulness can also be seen in the artist’s collection of empty cigar boxes, which he used in unconventional ways in his studio. He had a particular fondness for cigars, and at the time of his death many boxes were found scattered throughout his studio. He used them to store items, such as paint tubes, paint tools, glasses, and clips. These boxes were also a medium and subject matter for his paintings. Friends and family gifted the artist cigars knowing the box might later be used as the support for a small painting. From 1976 to 1979, Diebenkorn created a series of Ocean Park paintings on the lids of the boxes. These Ocean Park paintings in miniature are unique as they convey the same depth as the larger abstractions on canvas but are constrained to rectangles with dimensions no larger than 9” x 7.75”. In some of the paintings, particularly Cigar Box Lid #4 (1976), the Montecristo cigar brand label remains visible. This is clearly an intentional decision by the artist, since there are other areas of the composition where the label has been completely covered. As art historian and curator Sarah C. Bancroft describes,

“The printed text and images on the lids– which were often allowed to show through– serve as a layer within the composition, incorporated into the structure of the works. The transparency imparts a sense of depth, itself assuaged by the straight, diagonal, and curving filaments that cut through, exist within, demarcate, and glide over the panels or skeins of color, some incised as lines into the medium, others drawn, painted, or masked off.”3

In addition to the artist using the cigar box lids as blank canvases in the 1970s, Diebenkorn incorporated them as subject matter in his still lifes before his Cigar Box Lid series. By doing this, he continued the narrative of slowly bringing in his personality, figuratively and literally breaking down the barrier between his private life and work life. Flowers and Cigar Box (1954) presents a cigar box as a central figure alongside a flower vase and a single stemmed daffodil. Both are sitting atop a green and white textile, another device Diebenkorn used for both inspiration and subject matter.

Textiles are commonly depicted throughout Diebenkorn’s paintings and works on paper. These fabrics were saved in his studio and are now in the archives. Viewing them in person is an unreal experience. A fascinating aspect is that he does not aim to replicate every detail of the textile design but uses them as visual tools to create a compositional element in his work. Similar to the one in Flowers and Cigar Box (1954), a green and white textile is also depicted in the artist’s Still Life with Orange Peel (1955). Upon closer examination in person, this textile has a beautiful floral detail sewn into the green sections, a detail Diebenkorn chose not to include in his paintings. By leaving out the floral embroidery, it’s plausible that he did not see any importance in copying the textiles perfectly, but rather used them as a vehicle to purposefully bring in other visual elements to the work that it was lacking. In Still Life with Orange Peel (1955), the use of the textile does not overshadow the subjects on the table, but rather is placed to support them and further activate the space. As a counterpoint, the table background is duller, more muted, using shades of gray and red (even the glasses placed on the table are filled with brown liquid), while the green, almost turquoise, cloth paired with the orange peel brings a vibrancy that would not otherwise be there.

Another example of a frequently depicted textile is an Indian block print textile with a red border and interior floral pattern design. This textile can be seen in several works on paper such as Untitled (1964), the monochrome drawing pictured in the carousel above.4 Upon first glance, the textile can be seen as the focus of both pieces, taking up most of the frame in the works. It is being used as a tool rather than a subject. The actual subjects, specifically the utensils and candle, recede back and forth, blending into the background, allowing the textile and subjects to become synonymous. As Diebenkorn continued painting elements of these textiles, his use of them evolved over time. In the painting Recollections of a Visit to Leningrad (1965), he uses the same familiar textile but by removing the border he isolates the pattern. This fragment becomes a unique design and a compositional element that shapes the room. The artist uses the pattern as an instrument, repurposing its traditional association into something new.

Diebenkorn’s relationship with his functional tools and their integration in his studio and work sets him apart from others. The objects highlighted above are examples of this being true. As I spent time in the archives, I was reminded that the simplest and most functional objects can lead to some of the best creations. Often as artists we see our tools as investments and purchase the highest quality materials with the idea that it will aid in the production of the highest quality work. The Cigar Box Lid paintings achieve the same imaginative landscapes as the large Ocean Park abstractions, even on their limited scale and with disposable cardboard as the support. Furthermore, something as mundane as a tablecloth or bedspread becomes the inspiration for a pattern in several of his renowned paintings. Artists paint their surroundings, or their imagination, and somehow Diebenkorn was able to do both by making work derived from his creative space and the studio materials it held.

By studying artists who come before us, we open ourselves up to new techniques, methods, and cultures. I am beyond grateful for the opportunity to process the studio materials in his archives, spending time among some of the most intimate possessions of his artistic process. I now see Richard Diebenkorn as not only an artist but also a person, granting me a deeper connection to the artwork and the man behind the painting. My hope is that by examining these items from his studio, you will also gain a new perspective of Richard Diebenkorn and become inspired to create your own work from his experiences.

1. A small collection of Diebenkorn’s studio materials was given to the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. by the artist’s family in the early 1990s.

2. Essay by Dore Ashton in Richard Diebenkorn: Small Paintings from Ocean Park, exh. cat. (Houston: Houston Fine Arts Press; San Francisco: Hine, 1985), n.p.

3. Sarah C. Bancroft, Susan Landauer, and Peter Levitt, Richard Diebenkorn: The Ocean Park Series (Newport Beach, Calif.: Orange County Museum of Art; New York: DelMonico Books, Prestel, 2011), 28.

4. The fabric appears again in a print, #36 from 41 Etchings Drypoints.