Private Practice and the Studio Outside: Richard Diebenkorn Capturing the World for Himself, A Painter Taking Pictures

By Daisy Murray Holman

April 1, 2022

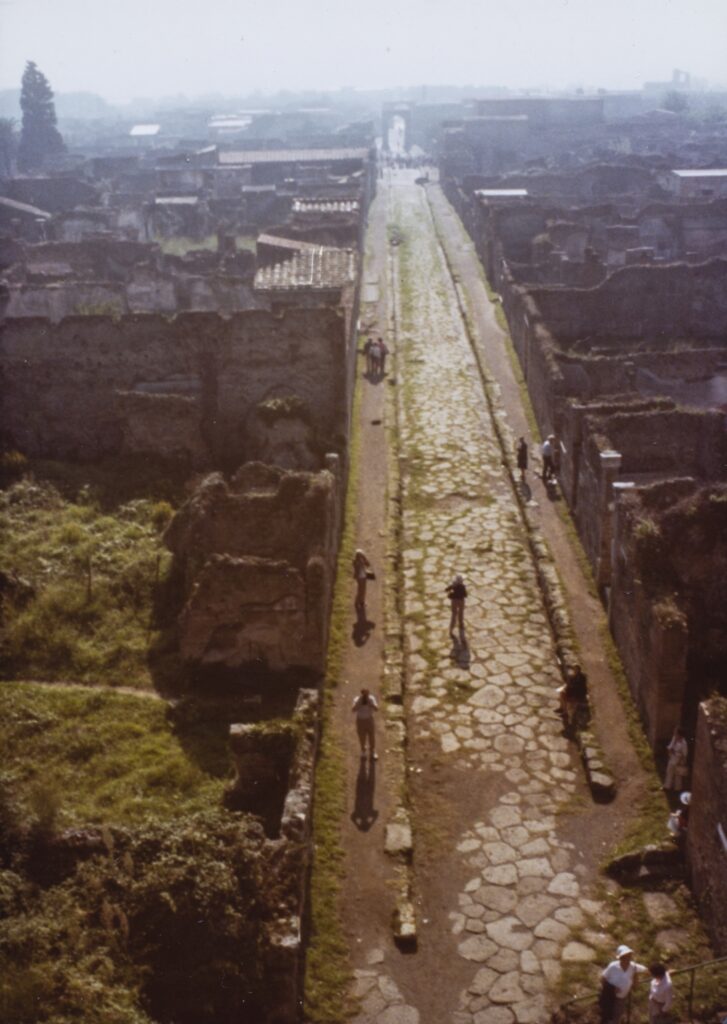

These photographs are a record of an activity I’ve engaged in since I was quite young, and it’s one of those I assumed everyone did – at least occasionally. When I was a boy riding in the family car in the country (very bored) I aligned telegraph poles. As the car moved and the scene altered I might watch one in the foreground as it approached another in the middle distance and at the moment they coincided I would make a click inside my head. This became a game – basically quite simple – but lending itself to much greater complexity and difficulty as such as, where the situation permitted, stacking two poles to make a quite high one or the aligning of members in three of more levels of depth, the click always defining the critical instant when a notable visual phenomenon was occurring “out there.” The game has endless possibilities of variation such as when fence rails move like arrows or battering rams and strike stationary targets such as buildings or animals or simply form momentary crosses in the landscape. The game doesn’t require an automobile either, since while simply standing on the street an airplane may be seen, during that click, to be adhering to building face or to a telephone wire.1

—Richard Diebenkorn, statement for Private Images: Photographs by Painters, exhibition at Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1977

I think of “seeing” as a kind of constant — In that sense there was no change in the perceptual process. However, one is continually perceiving the painting itself in process, and this brings about a mix with the conceptual. It’s a different mix with representation. In regard to the second part of your question, I didn’t start seeing differently, I simply saw different things.2

—Richard Diebenkorn, 1983

Whenever we would cross the San Francisco Bay Bridge, my father would notice the color of the water and comment on it. And some days it was more khaki colored. Sometimes it was beautiful, beautiful blue. It wasn’t that we needed to name the colors. It’s that we needed to notice and that’s one of the most important things I learned from him was the value of really looking and then finally seeing.3

—Gretchen Diebenkorn Grant, 2019

In 1987 Richard and Phyllis Diebenkorn left Santa Monica, where Diebenkorn had been painting his iconic Ocean Park series over a twenty year period, for a quieter next chapter in Healdsburg, California. A town in rural Anderson Valley, a region known for its vineyards, they moved into a widow’s walk Victorian home, built a small building on the property for an office and guest house, and converted the barn into a studio. A lifetime of papers and photographs were packed up and put into different corners and closets. The Diebenkorns filled the house with their beloved art and carefully selected objects, placing each item with care and in their own particular way of organizing their space. The house became a snapshot of how Diebenkorn constructed his reality: in essence it mirrored how he saw the world.

Diebenkorn died less than six years after they moved to start anew in the house overlooking a vineyard and with a view of Mt. St. Helena, and Phyllis spent the next twenty years caring for the home and all of the materials held within. Until Phyllis’s death in 2015, trusted friends could visit the Healdsburg home and be immersed in Diebenkorn’s visual reality. A central hallway extends back from the front door. A grand staircase runs up one side. The family, however, prefers to enter the home from the side through the back porch. Walking down the hallway toward the front door, a small landscape painting by the artist’s maternal grandmother hangs on the wall. As the front door opens, the physical presence of Mt. St. Helena rises in the distance, a sight the artist considered and spoke about. When the Diebenkorns first moved into this home, he composed the opportunity to see both the painted and the real mountain at once, or at least to hold the memory of the two together. This essay is a study of the compositions Diebenkorn left behind that exist outside of his paintings and works on paper and provide one with insight into his way of seeing. These compositions are both in the physical spaces he inhabited and the photographs he took over a pivotal twenty-plus years of his career which reside today in the artist’s archives.

The personal archives of a public figure can confirm factual information, but an archive can sometimes leave just enough nuance and space for a researcher’s conjecture. We can resolve the question of a date or an address or where they went to school or who they taught alongside, but once the individual is gone the intent behind their materials begins to fade. The nature of archives invites the question: what is the place of an artist’s biography in the study of visual art? In this case, what do Richard Diebenkorn’s archives tell us about his work? Do youthful love letters give us more insight into a painting’s meaning? What does a professional document tell us about a major point of transition within his work? As artists’ archives have become a fixture in art history and legacy preservation, the question of relevance grounds our desire for synthesis with the obligation we have to the artists themselves: we aim to maintain their privacy while upholding the primary importance of their artwork.

In the case of the photographs, correspondence, and documents that constitute the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives, there is no area within the collection that more distinctly invites this question than the photographs taken by Diebenkorn himself. The repository holds over 1,500 pictures taken by the artist throughout his years of painting. The bulk of the photographs were taken between 1962 and 1987 while traveling with his wife, Phyllis, throughout California, the American Southwest, and Europe. There are very few candid family photographs known to be taken by Diebenkorn, making this activity of picture taking unique to his travels. Until 1977 we have no known prints of the photographs, only images existing in primarily 35mm slide format. While potentially rich with insight and compositional value, we wonder: were they meant to be seen at all?

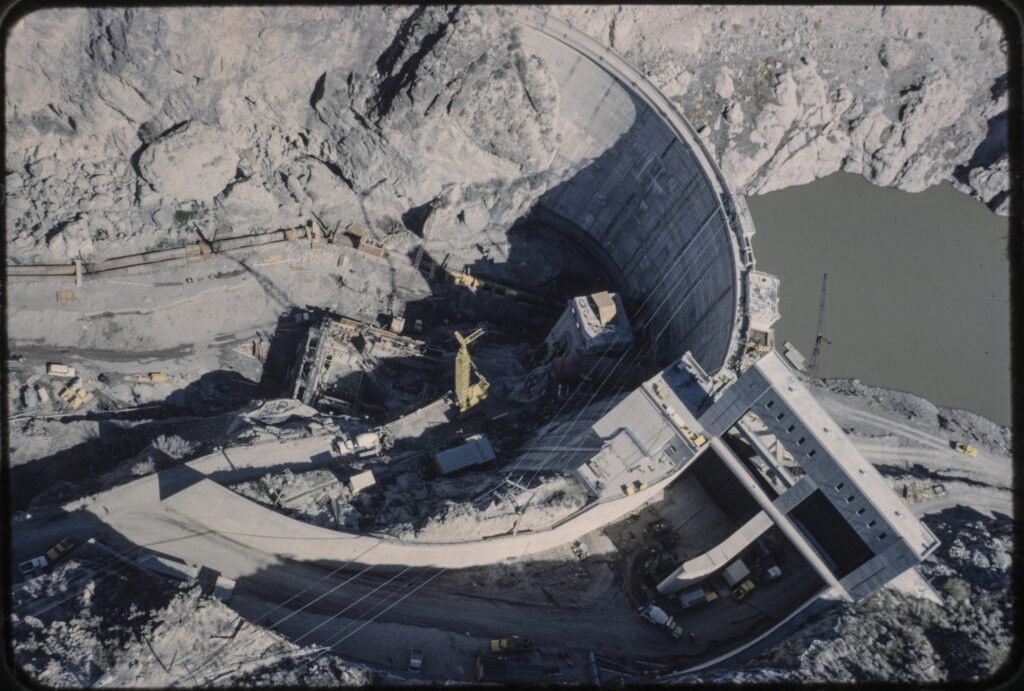

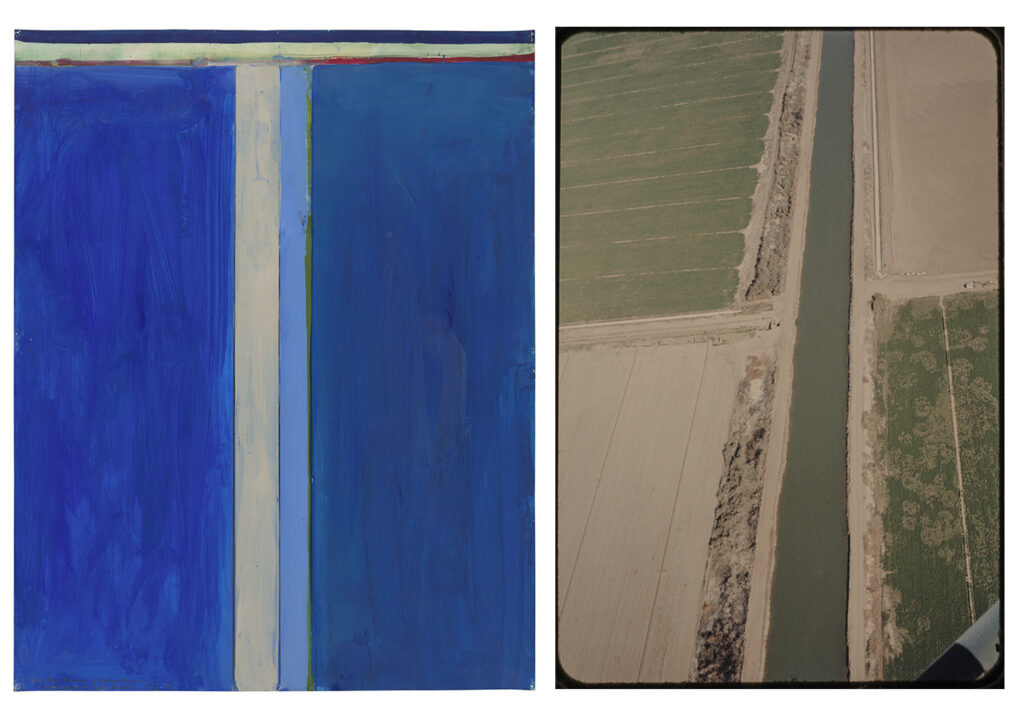

Permission to evaluate the photographs can come from Diebenkorn himself. The artist and his family preserved the negatives and slides for over a half century, and during his lifetime Diebenkorn carted them between three different residences and multiple studios. Eventually he did begin to print his travel pictures (or did not protest when someone else printed them). Significantly, in 1977 he shared at least one photograph with curators Maurice Tuchman and Stephanie Barron which was included in an exhibition of “painters’ pictures” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.4 In the accompanying quote, he does not deny the presence of the activity and instead speaks of it as a visual tool throughout his life. Either the curators knew Diebenkorn occasionally took pictures or Diebenkorn volunteered the information, but clearly it was not a private pursuit. The same photograph and an additional one, both taken during a helicopter flight in 1970, were reproduced in curator John Elderfield’s essay in the exhibition catalogue for Diebenkorn’s 1988 drawing retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.5 Diebenkorn was closely involved in the project and reviewed Elderfield’s essay before publication.

While Diebenkorn may have publicly acknowledged his pastime behind the lens, Phyllis Diebenkorn held onto the photographs for another three decades. In 2014, she gifted the photographs, documents, correspondence, and studio materials to the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation, with the understanding that the documents would be preserved as an archive for study and research. Since her husband’s death in 1993 Phyllis had been the guardian of her husband’s legacy, and she shared the photographs and documents with trusted researchers, scholars, curators, and friends. Eventually the number of requests increased and her desire to protect the materials changed. The Foundation’s acquisition of the artist’s archive allowed for new discoveries of the artist’s process previously lost to time or memory. The transfer of ownership from the private sphere to the public sphere gave us permission to make our own discoveries through a piece of correspondence or a tiny slide revealing a studio wall. As we celebrate Diebenkorn’s 100th birthday, nearly 30 years after his passing, the photographs are what we make of them.6

The Cityscape Photographs

During the making of the drawings and paintings catalogue raisonné, the Foundation staff made regular research visits to Phyllis Diebenkorn’s Healdsburg home from 2012 to 2014. Phyllis graciously welcomed her visitors and started their morning with a strong cup of coffee before they dug into the materials in the office. She cooked a simple lunch which the parties enjoyed together at her table, the walls covered with Diebenkorn’s art and suffused with his memory.

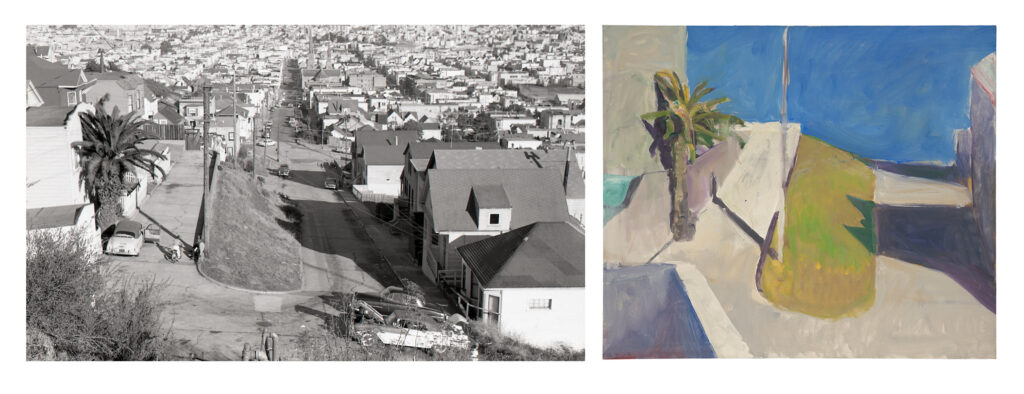

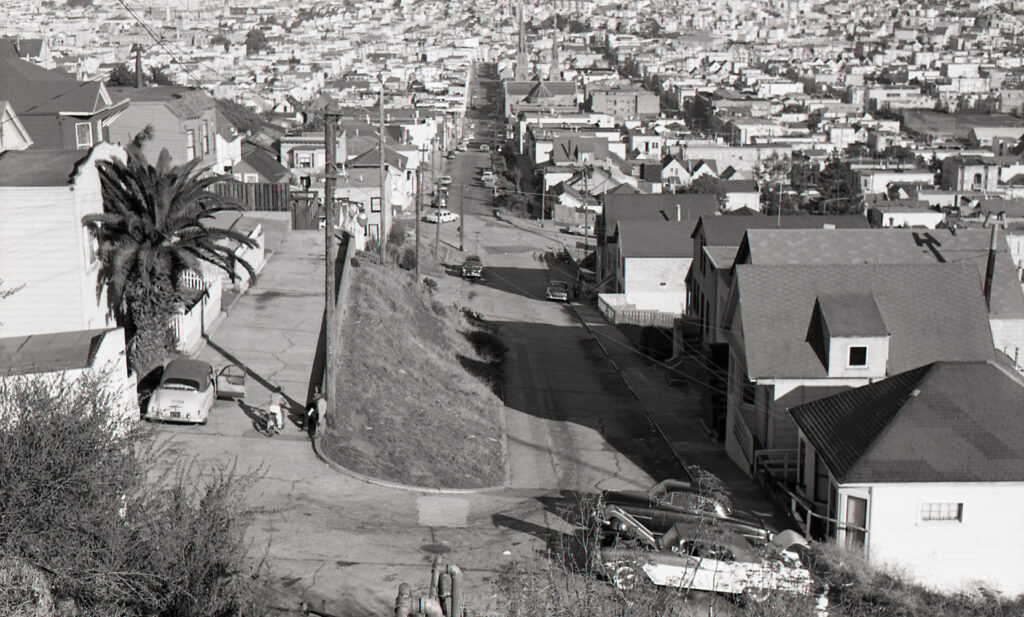

During one visit in 2013, some 35mm film bearing Diebenkorn’s unmistakable handwriting was unearthed. The film had been cut into strips and placed in sleeves: four strips were labeled “10-23-63 S.F. Sun,” two bore notes of “no prints,” and two were unlabeled. At first glance the film seemed to be street scenes taken by Diebenkorn while driving through San Francisco. The images appeared anonymous but familiar. One who knows Diebenkorn’s paintings from the 1960’s could see the verisimilitude between the compositions captured in the photographs and Cityscape #1 (1963) and Cityscape #2 (1963). It was more than striking. It was almost exact. The relationship between the framed urban landscapes of the photographs and the framed oil paintings was undeniable.

Cityscape #1 is one of Diebenkorn’s most well-known paintings. It carries an aura of mastery, demonstrating an artist confident in his ability to synthesize mind and hand. The Cityscape paintings are examples of Diebenkorn painting recognizable spaces. Eight years prior, in 1955, as Diebenkorn matured in his representational painting style, he made a small landscape titled Chabot Valley (1955), which the artist noted was made using a practice he developed while a student at Stanford University (1940-1943), to “get in the car and go out and look for something”7 to paint. The artist’s transitions between representation and abstraction are well documented, but the lulls within each period have garnered less attention. Diebenkorn was highly productive between the years 1956 and 1963, completing an average of thirty-eight paintings a year during the nine year stretch, with fifty-six oil paintings in 1962. Two years later, in 1964, he signed a single work on canvas. Biographical information has helped us consider this precipitous drop,8 but the presence of Diebenkorn’s photography tells us that while he was taking a break from the canvas he was still looking deeply at his surroundings and creating compositions from what he saw “out there.” For the 1964 lull in particular, Diebenkorn’s physical surroundings were disrupted by the events of moving both studio and home, while also traveling extensively.9 Diebenkorn went on these journeys with camera in hand, maybe, as he acknowledged about Chabot Valley, looking not to capture a memory but “something that … might make a good painting.”10

In 1963, Diebenkorn returned to Stanford University as the school’s first artist-in-residence,11 and Phyllis and he moved to Palo Alto for the academic year of 1963-64. While there, he continued to regularly commute to San Francisco, to attend drawing sessions with Elmer Bischoff and Frank Lobdell, and to Richmond in the East Bay, to print with Kathan Brown at Crown Point Press. Of his residency Phyllis noted that Diebenkorn focused on drawing, as it was hard to paint when he had students coming in and out of his studio.12 However, with this dated film we can show that Diebenkorn painted the entire Cityscape series while living in Palo Alto. There must have been something about his trips throughout the Bay Area, wheeling through San Francisco, the “clicking” of the shadows across the street, or a palm tree jutting into the sky, that compelled him to paint. Or maybe it was the muscle memory of leaving the studio and looking to his surroundings for a subject while working on campus. A completed Cityscape #1 is photographed in 1963 in the Stanford studio at Christmas time. Since all of the Cityscape paintings are dated from that year, one can assume Diebenkorn completed them in a matter of weeks after his October sojourn.

The “10-23-63” film (believed to be from two short rolls) tells us that Diebenkorn did, at least once, capture a landscape on film for use as direct source material, and his notes on the film sleeves suggest that he did make prints from the negatives. The photographs capturing scenes depicted in the Cityscape paintings are all in the sleeves marked “10-23-63 S.F. Sun.” He was likely not relying on what would need to be a nearly perfect photographic memory to recreate the shadows and the curves of the streets in Cityscape #1 and Cityscape #2. During a time when he was struggling to paint, he relied on the old method of driving around, moving through space and looking, to help him get back to work. Now with a camera to document what he was seeing, he gained the ability to freeze the compositions he intersected during his ramblings.

The Visual Phenomenon “Out There”13

John Elderfield wrote about the interaction between Diebenkorn’s drawings and paintings, saying:

“At times… drawing posits a grand design, a latticework of options to be considered one by one. At others, it functions rather like those gouged holes modelers will sometimes put in their sculptures to provide a way back into the work that has come to an impasse: as an irritant and means of reentry. And at yet others, it will be a finally resolving component, the necessary girder that makes the structure stable and complete.” 14

While we cannot swap out the word drawing for picture taking, the pictures may help us see that taking in the world around him, what he saw “out there,” served to add to his tool kit while helping him reconcile numerous compositional struggles in the studio. Maybe the visual game he played all his life was a catalyst for the pentimenti that forms the structure of so many of his works. The compositions captured in the photographs were all available for him to rely on as source material whenever he faced the blank paper or canvas or a difficult moment within the work. Like his library of paintings by Cezanne or de Kooning, one can imagine him flipping through the images, as if stored in a filing cabinet, when moving his hand across the canvas or page, whether at a moment of impasse or to inform the potential of his line to carry memory and narrative.

Elderfield views Diebenkorn’s 1970 photographs as demonstrations of a crucial polarity he sees in the artist’s work between imagination and reality.

[Diebenkorn’s] work, he says, is “always swinging back and forth between pared-down simplicity and an attempt to hold on to the incidentals.” He wants to preserve the incidentals, to retain what seems particular, isonic, and charged; and he also wants an open and spare relational art. He wants something near and urgent that is also distanced and harmonized. But there will be times when he wants one of these options more than he wants the other.15

To Elderfield the photographs point us to the intrinsic pull between imagination and reality inherent in Diebenkorn’s work: the photographs demonstrate reality. But with the opportunity to see hundreds of them at once, the particular reality Diebenkorn was seeing becomes very clear. Imagined or not, it was not the same world seen by everyone else. The artist has the power to transform reality with their imagination, especially if imagination is a different way of seeing.16

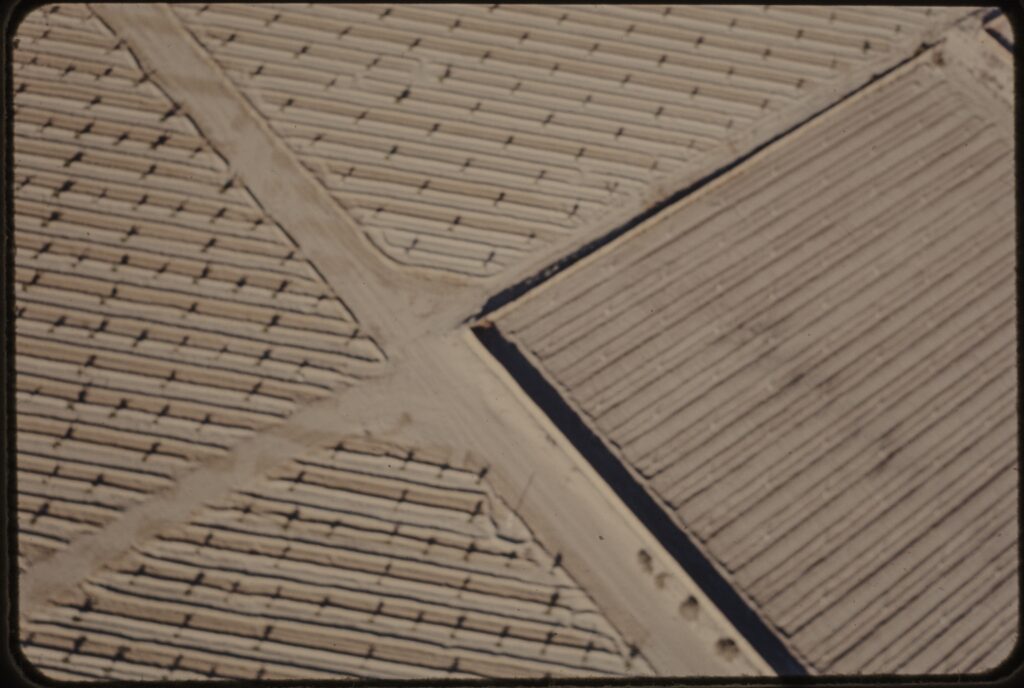

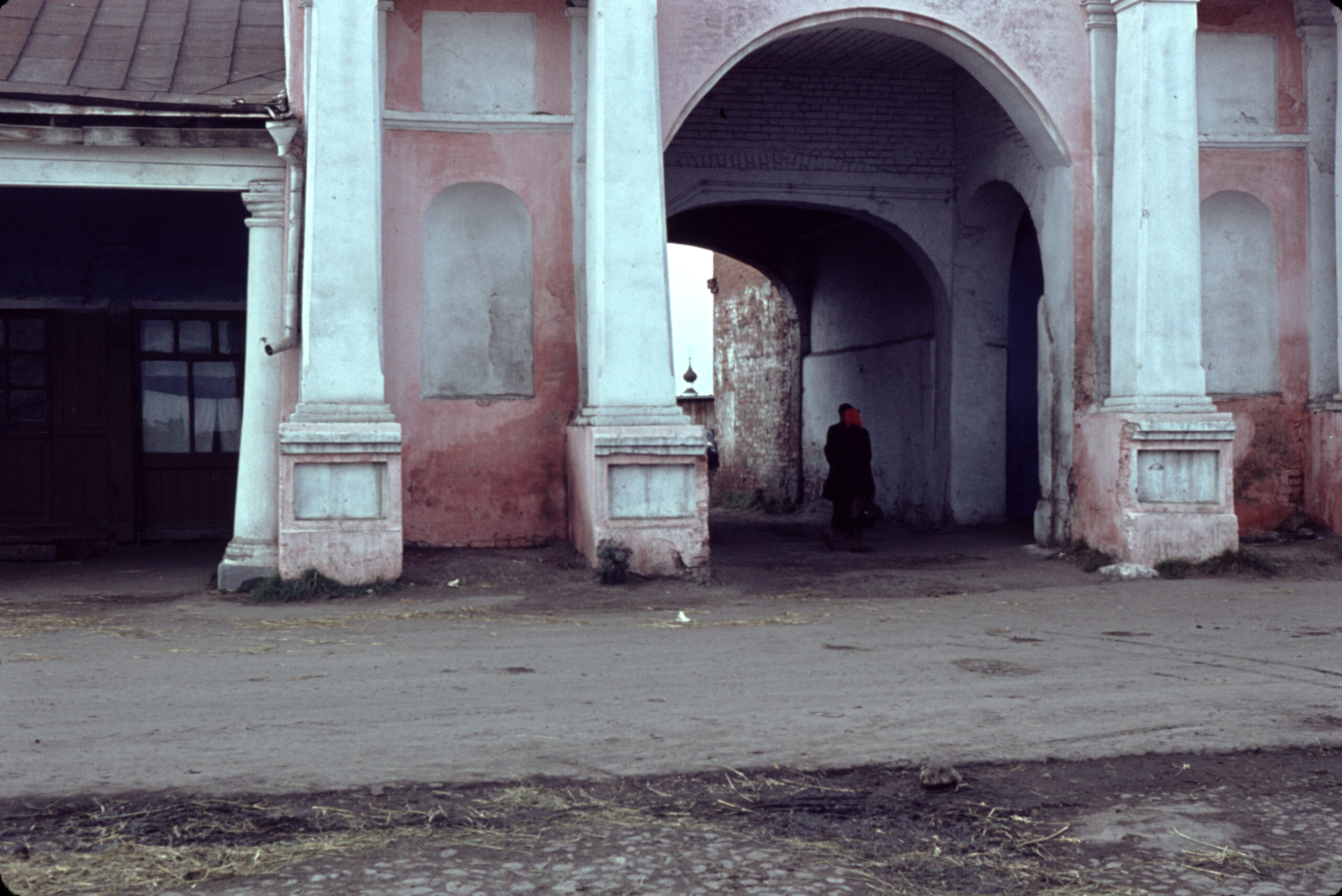

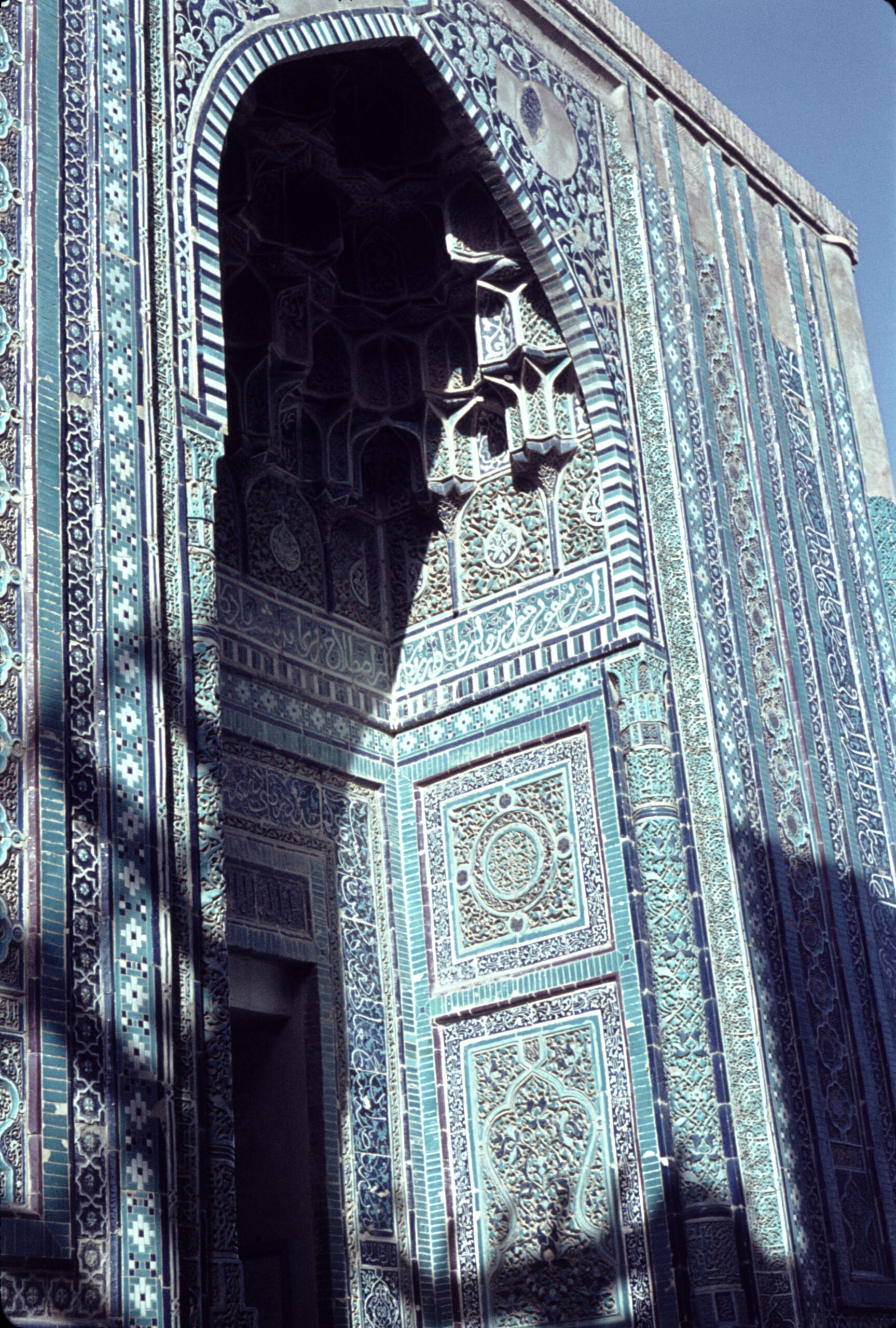

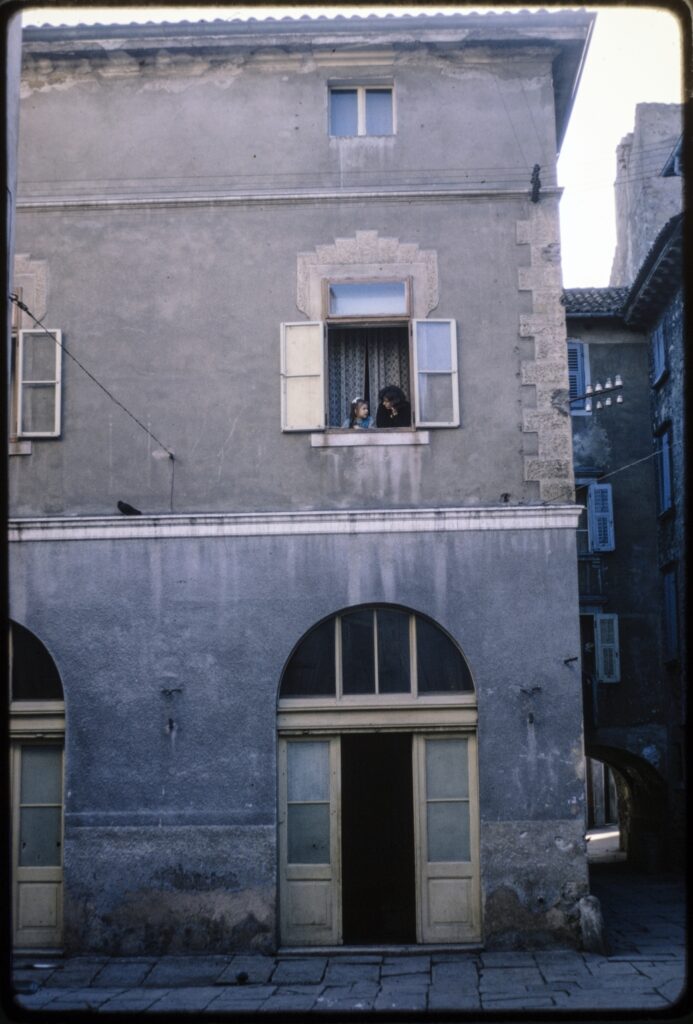

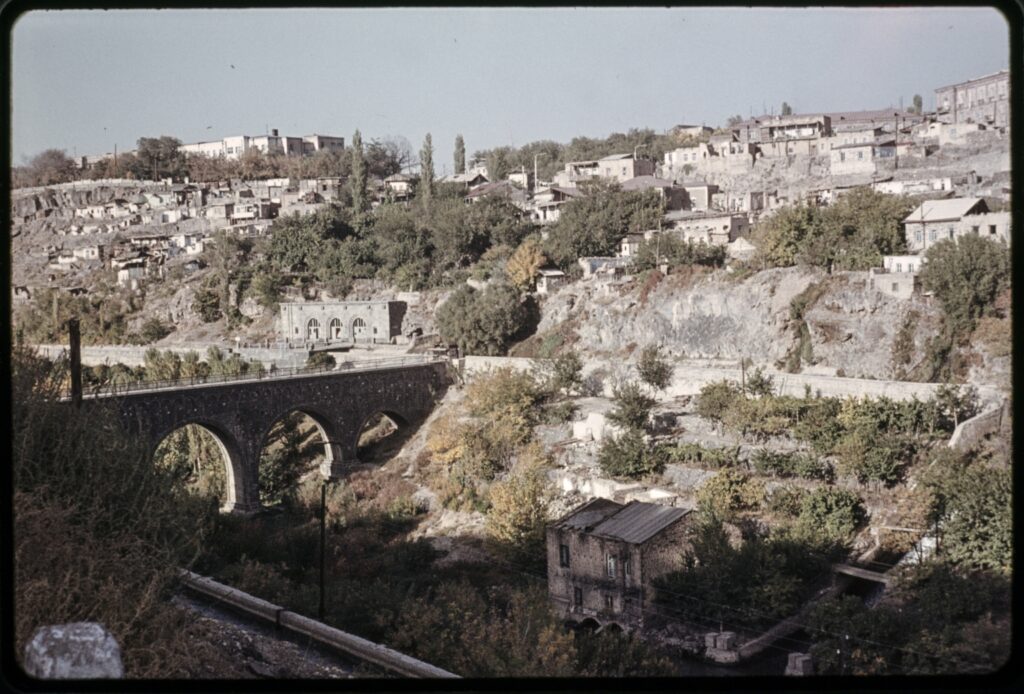

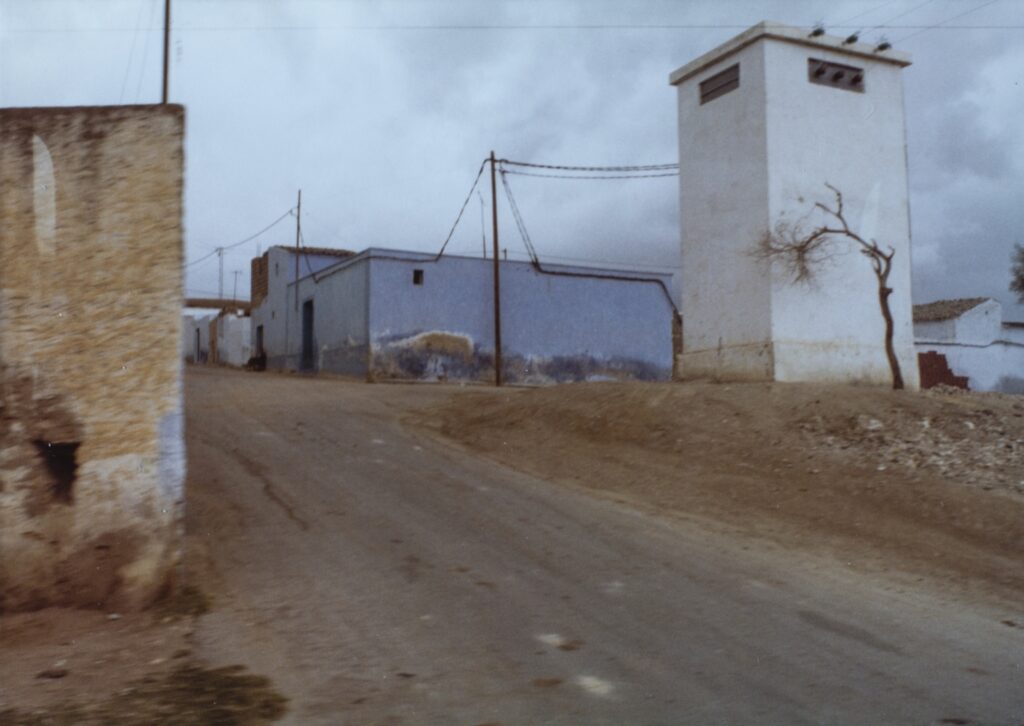

Now that the photographs are out in the open we can take a closer look at what he captured. What was it that Diebenkorn was seeing? These are not “my trip to France in 1966” photos, but “the angle of the sun on the earth as I saw it from here” photos. There are a few pictures of Phyllis eating a meal, having a picnic, and occasional scenes of a particular ruin or landmark, but the majority of the photographs reveal the landscape, often not a recognizable one. In no particular order, here are the primary themes: tripartite structure, ground, landscape, sky. A deep foreground, often focused on the barrier between his location and the view in front of him, as in a patio wall, a boat railing, a window frame or an airplane’s wing. Movement, primarily his own through the world while viewing a stationary subject, the motion evidenced by a stretch of blurred road or the wake of a boat. Perspective, a hillside from below with terraced fields, or looking up at the sheer face of a building wall, or what we see when we crane our necks. His beloved aerial view, either from a plane, a storied window or a balcony. Capturing farming patterns and crop circles, roof tops, shorelines. Geometry, a clear and striking architectural and agricultural structure, a focus on intersecting lines, the combination of buildings pressed together, windows and doors, and construction scaffolding. The archways beneath a bridge or an aqueduct’s support system. Windows and doorways on a textured wall, layers of paint and the pattern left behind. Shadows, cast by the rhythm and stillness of girders and beams.

Overlaps between the captured photograph and the work of art vary from an acknowledged source—photographs taken from a helicopter over the Lower Colorado River Basin and the aforenamed drawings from 1970— and a whisper of reference—three photographs of the residue from a poster torn from a wall in France from 1978— that do not suggest one particular work but evoke the lines from numerous Ocean Park works on paper. The Lower Colorado pictures were taken while Richard Diebenkorn was flown by helicopter over the water-reclamation sites in the Salt River Canyon in Arizona, and the trip was the impetus for the first completed series of Ocean Park works on paper.17 These pictures also became the photographs included in the 1977 LACMA exhibition curated by Tuchman and Barron, and later reproduced and discussed by Elderfield in 1988. Diebenkorn said that he did not produce “documentary drawings” on the trip, but instead created “abstract impressions.”18 Connecting the abstract impressions with the scenes Diebenkorn framed and captured on film reveals Diebenkorn seeing the world reflected in his paintings, while also seeing his paintings reflected in the world.

Undeniable compositional similarities and subjects connect the two mediums, and comparing the artist’s output with the action of picture taking further positions photography as a tool he trusted. Photographs began to appear in 1962, continued throughout the 1960s, and peaked in the mid to late 1960s (coinciding with the aforementioned lull in painting, 1964-1966, and producing fewer works on paper beginning in 1968 until the early 1970s). The dates of the photographs line up with both the artist’s slight shift in style and medium preference as well as with the seismic shift from the Berkeley representational work to the Ocean Park abstraction series. Diebenkorn moved homes and studios nine times between 1963 and 1970. These pictures record movement, physically and conceptually.

The photographs exist as visually seamless counterparts to Diebenkorn’s artwork. They appear to fill the place of a sketchbook when traveling; while Diebenkorn was rarely without pencil and paper at home, we know only a few examples of travel scenes within the sketchbook pages. That Diebenkorn took the pictures is certain, as Phyllis openly denied ever taking a picture, and Gretchen remembers seeing her father behind the lens. Luckily, Diebenkorn did occasionally capture a few intimate scenes and views from his own home, giving us an inside peek as to how he really saw it. It is no surprise that the composition between a photograph from Europe and one from his home patio is the same. We can see the patio wall, then the hills, and the sky, a classic tripartite view. The geometry of an overpass in the distance, telephone wires crisscross through the view.

Even keeping parallax in mind, knowing he was moving at a speed of 65 miles per hour on an open highway, or standing still in the midst of a busy piazza, or pausing during a quiet walk, Diebenkorn was playing the game. Here is the moment when the objects lined up into a new form, here is the fence post in the moment it became a “battering ram.”19 He is looking through the viewfinder at the way the railing, the ledge or the wall created a foreground and split the world into the tripartite environment he discovered in the framing of the Bayeux Tapestry postcards his grandmother gave him as a child.20 He was finding Hopper’s windows and Matisse’s interior and exterior juxtapositions throughout urban and rural architecture. When Diebenkorn was away from the studio, without pad and paper, and in flux, he never stopped seeing. The pictures allow us to peek inside his vision, to step into an insider view, an opportunity made possible only by this artist’s archive. Diebenkorn’s photographs powerfully present his choice to capture the distinctive world he saw within that very essential “click.”

1. Richard Diebenkorn, statement reproduced on exhibition poster, Private Images: Photographs by Painters (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1977).

2. Richard Diebenkorn, interview with Jan Butterfield, Resource/Response/Reservoir—Pentimenti: Seeing and Then Seeing Again (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1983).

3. Gretchen Diebenkorn Grant, video interview, May 30, 2019, https://www.instagram.com/tv/ByGGfD_lVGr/.

4. Diebenkorn, statement on poster, Private Images.

5. John Elderfield, The Drawings of Richard Diebenkorn (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1988), 54-55.

6. The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives consist of the professional and personal papers, correspondence, photographs, studio materials, and ephemera transferred to the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation by Phyllis Diebenkorn in 2014. The archives are currently accessible by request through the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation website, www.diebenkorn.org.

7. Richard Diebenkorn, oral history interview with Susan Larsen, 1 May 1985, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

8. Richard Diebenkorn, Sr. was diagnosed with terminal cancer in April of 1964, and passed away in June of that year in La Jolla, California. Diebenkorn spent the month there to help his mother.

9. The Diebenkorns traveled to Europe and the Soviet Union during the Fall of 1964. Diebenkorn was selected to be a representative of the United States with the Department of State’ Cultural Exchange Program.

10. Richard Diebenkorn, oral history interview with Susan Larsen, 1 May 1985, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

11. In 1963 Richard and Phyllis Diebenkorn moved from Berkeley to Palo Alto for one academic year (1963-64) where he was the first artist-in-residence at the university.

12. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Benjamin Grant (grandson of the artist), 2003-4.

13. Diebenkorn, statement on poster, Private Images, “the click always defining the critical instant when a notable visual phenomenon was occurring ‘out there.’”

14. Elderfield, 33.

15. Ibid.

16. Diebenkorn’s daughter, Gretchen Diebenkorn Grant, commented that her father was particularly interested in tales of transformation as a child, pointing out particular moments to her in the Oz books written by L. Frank Baum and illustrated by W. W. Denslow. Diebenkorn was most interested in the stories that captured the space between fantasy and reality. He pointed out to her that while the difference between the two was critical, it was equally important to understand that the elements of fantasy can all be found in reality. Gretchen Diebenkorn Grant, conversation with author, January 17, 2013.

17. In 1970 Diebenkorn participated in the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Reclamation project inviting forty prominent American artists to document the Bureau’s projects in the Lower Colorado River Basin. He was flown over the Salt River Canyon in Arizona by helicopter and took numerous pictures. He said “I think the many paths, or pathlink bands in my paintings may have something to do with this experience, especially in that wherever there was agriculture going on you could see process—ghosts of former tilled fields, patches of land being eroded.” Richard Diebenkorn quoted in Dan Hofstadter, “Almost Free of the Mirror,” New Yorker, 7 Sept. 1987, 60-61.

18. Richard Diebenkorn quoted in Dan Hofstadter, “Almost Free of the Mirror,” New Yorker, 7 Sept. 1987, 60.

19. Diebenkorn, statement on poster, Private Images.

20. Diebenkorn’s maternal grandmother, Florence Stephens’ gifted the young artist numerous influential books and materials. One of which was a set of postcards of the 230 foot Bayeux Tapestry, the 11th century cloth embroidery depicting the Norman invasion of England. Each postcard in the set is a segment of the Tapestry.