The World by Air: The Making of the Lower Colorado Series

By Jacquelyn Northcutt

October 19, 2023

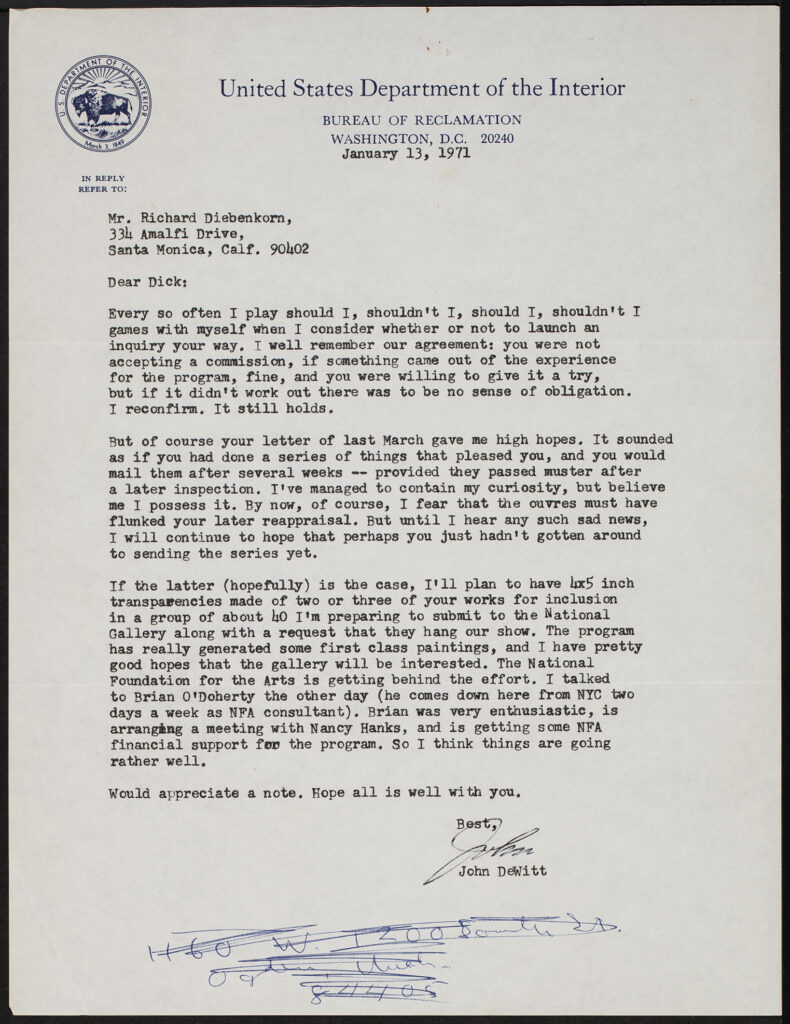

December 5th, 1978

Dear Dick:

Off and on for quite some time I have thought of mounting a modest sized exhibition of your work based on the eight pieces you did for my Reclamation art program some years ago. It has seemed to me—as it has to a number of others I have talked to, starting with Jerry Nordland—that your helicopter trip over the lower Colorado and the work that came from it led directly to your Ocean Park series.

The working title of the show would be The Bridge To Ocean Park. It would include a selection of four (say) of [your] paintings done in the year just prior to your Reclamation work, the eight small Reclamation pieces, and then four of the more subjective Ocean Park paintings that came afterward.

The show could open in Washington (I know people there who are interested) and then go on tour to a few selected museums around the country. My guess is that Henry Hopkins, for one, would like to hang the show. I don’t think it would be a difficult show to book at all. I would look for a catalogue grant from the NEA.

If the idea appeals at all I would be delighted to hear from you. I’m planning a trip west later this winter and could easily include L.A. in my itinerary.

Note my new address above. I have finished with the Fed Govt now and returned to my home port, where I’m doing some sculpture and some writing, and otherwise taking life a bit easier.

Best regards,

John DeWitt

P.S. I still remember that helicopter trip as being one of the more enjoyable highlights of my career as a minor bureaucrat.

John DeWitt sent this letter to Richard Diebenkorn in 1978, while the artist was living in Santa Monica, California. At this point, Diebenkorn had established himself as one of the most distinguished living American artists and had garnered significant attention after once again breaking away from the common artistic trends of the era, embracing a layered and geometrically grounded approach to abstraction in his ongoing Ocean Park series. Galleries and museums across the United States often offered him invitations for solo exhibitions, and he earned a mid-career traveling retrospective exhibition organized by the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in 1976. His success made him a desirable person with which to work, and for former employee of the Bureau of Reclamation John DeWitt, the opportunity to build an exhibition featuring such an artist was appealing.

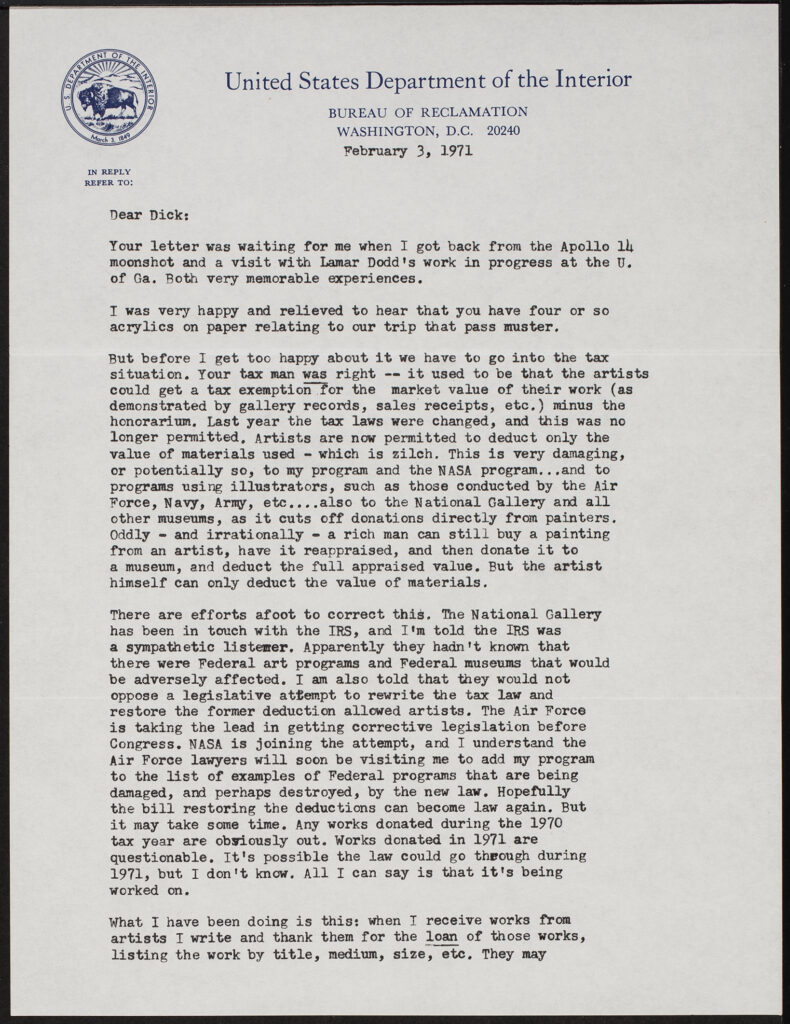

Diebenkorn and DeWitt first connected several years earlier while DeWitt was working for the Bureau of Reclamation, a subdivision of the Department of the Interior that focuses on building water conservation projects (including dams, hydroelectric plants, and irrigation systems) throughout the Southwestern United States. The rise in concern over the need for environmental conservation throughout the 1960s brought new scrutiny to the Bureau of Reclamation’s construction activity in natural landscapes. In an attempt to shift the public conversation around its projects, the bureau drew inspiration from other federally-funded art programs such as the Department of the Air Force Art Program (started 1950) and NASA’s Artist’s Cooperation Program (started 1962) and started its own program that commissioned work from artists throughout the country. Between 1968 to 1974, the program oversaw the creation of almost 400 works of art created by 40 different artists, including Horace Day, Joseph Hirsch, Anton Refregier, and Norman Rockwell.1

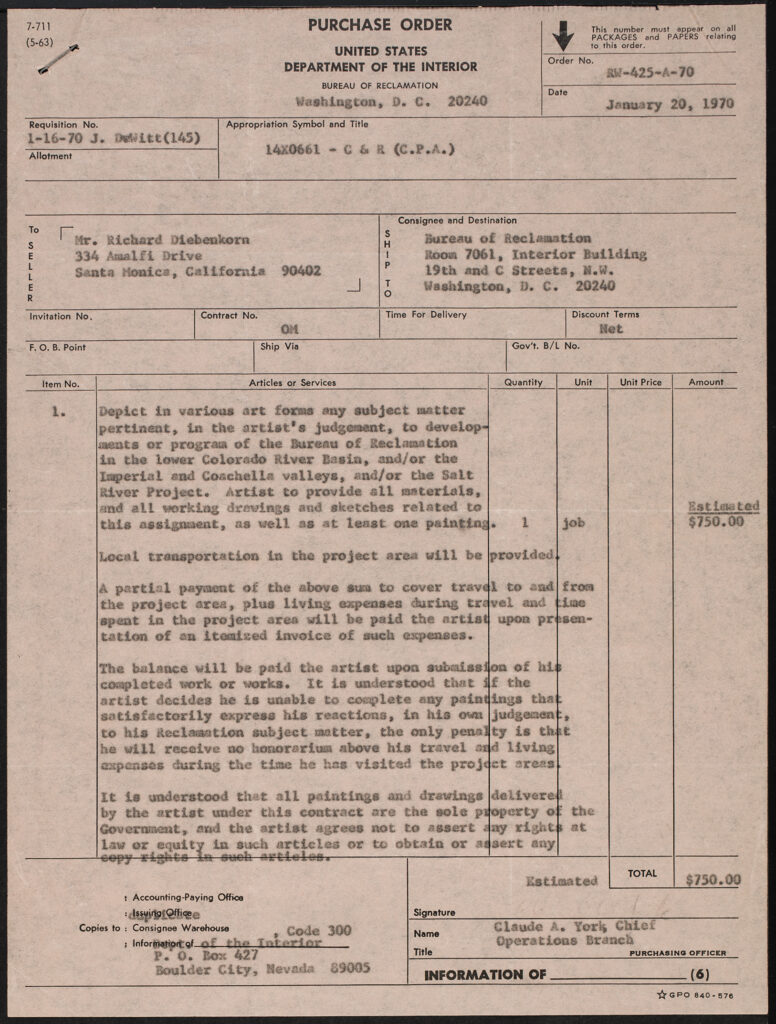

In January of 1970, John DeWitt wrote to Richard Diebenkorn asking him for the second time to join the program and go on a trip that would take place in February of that year. In the letter, DeWitt writes,

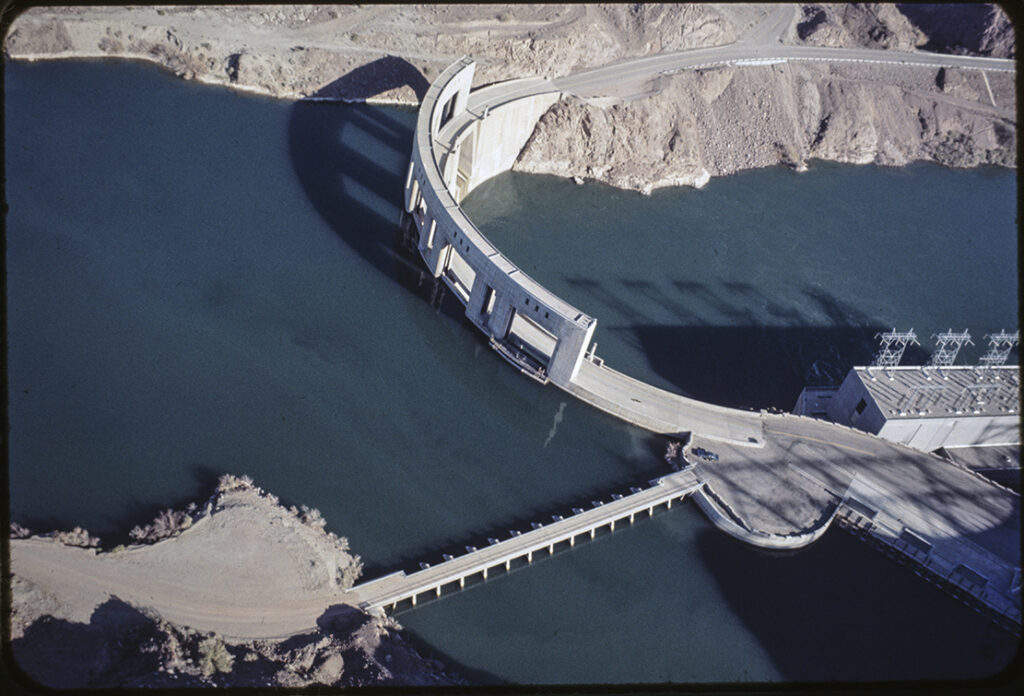

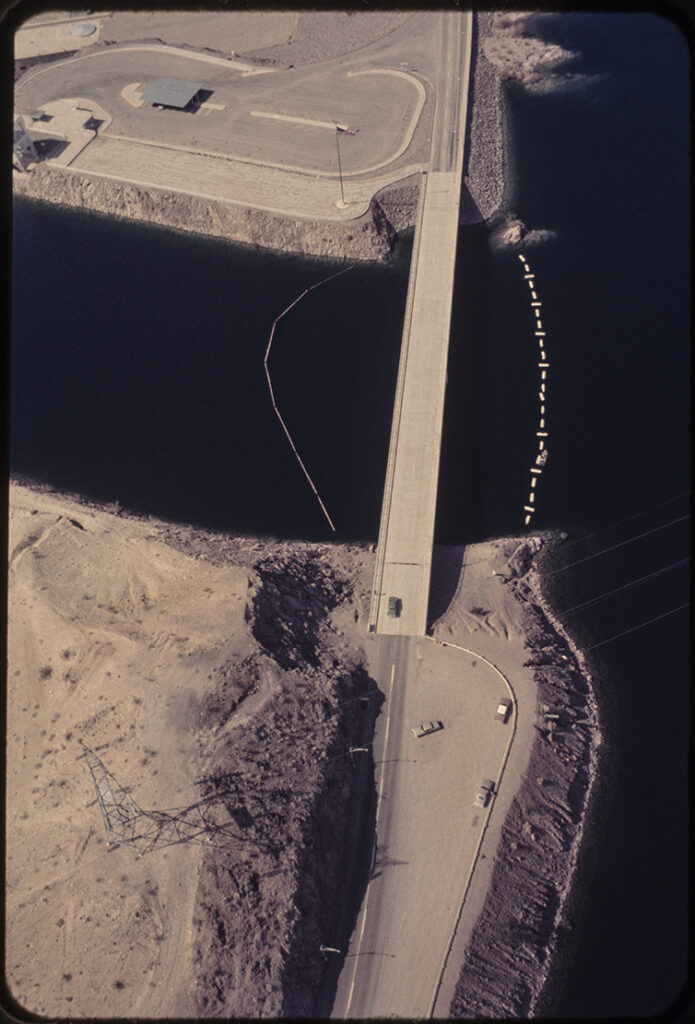

“I plan to meet the artists in Las Vegas, spend a day or so looking over Hoover Dam and Lake Mead by car and boat, then take a helicopter…and follow the course of the Colorado River down as far as the Mexico border, putting down wherever anyone wanted to sketch or take photos. We have a number of project works on the way down the river, and scenic spots such as Topock Gorge. Then we would fly over the All American Canal to the Imperial and Coachella valleys and the Salton Sea…The next day we would fly back to the Yuma area, then on to the vicinity of Phoenix and our Salt River Project, including some reservoirs in the mountains east of Phoenix. After the helicopter trip each artist could choose whichever areas appealed most to his painterly instincts and go back there by rental car (on us) for as long as he cared to. I would probably follow around to each location in another car to be sure all were receiving whatever services they needed. The weather should be ideal in the southwest desert country this time of year. Wives are welcome on all but the helicopter part of the trip (no room).”2

In this letter, DeWitt also clarifies that Diebenkorn’s current predilection for abstraction was welcome in the program: “I am not seeking purely representational painting, as I explained in my first communication. Imaginative abstractions are fine. I know your work and admire it, though I have not seen your most recent work. If you have now eschewed the figurative entirely, this still won’t interest you. But if you haven’t, and if I happen to kindle a spark, please call me collect anytime.”3

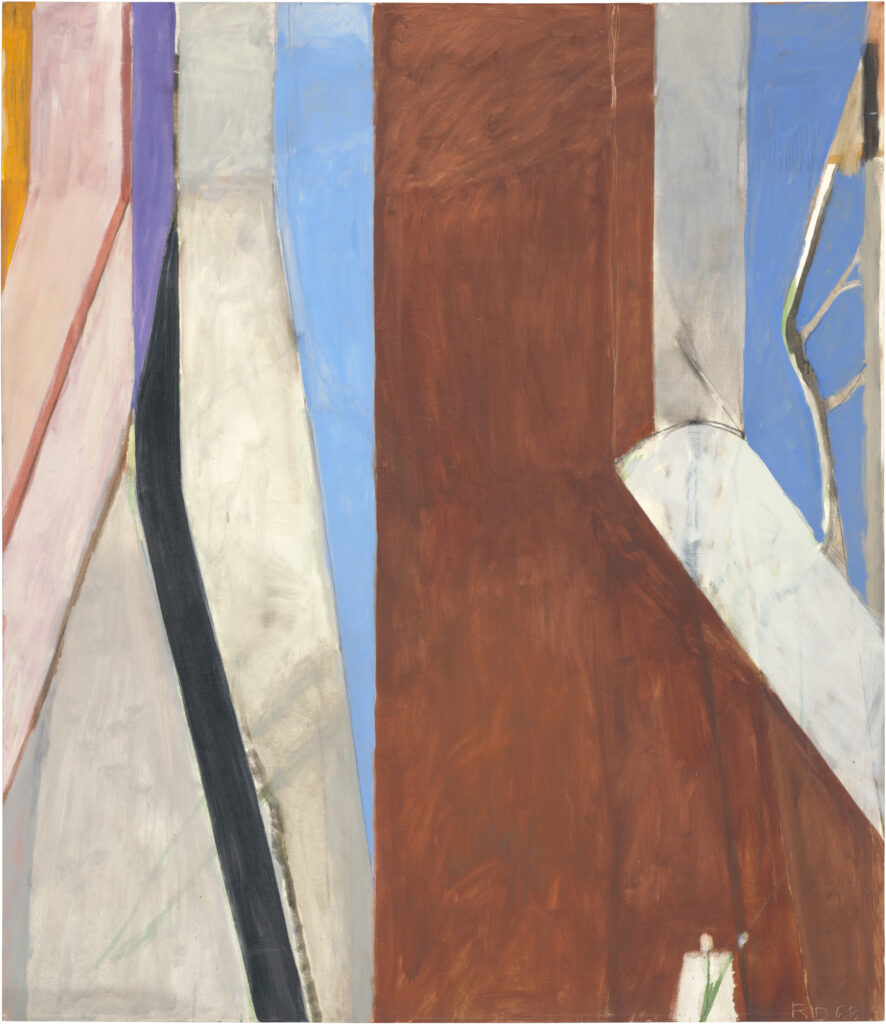

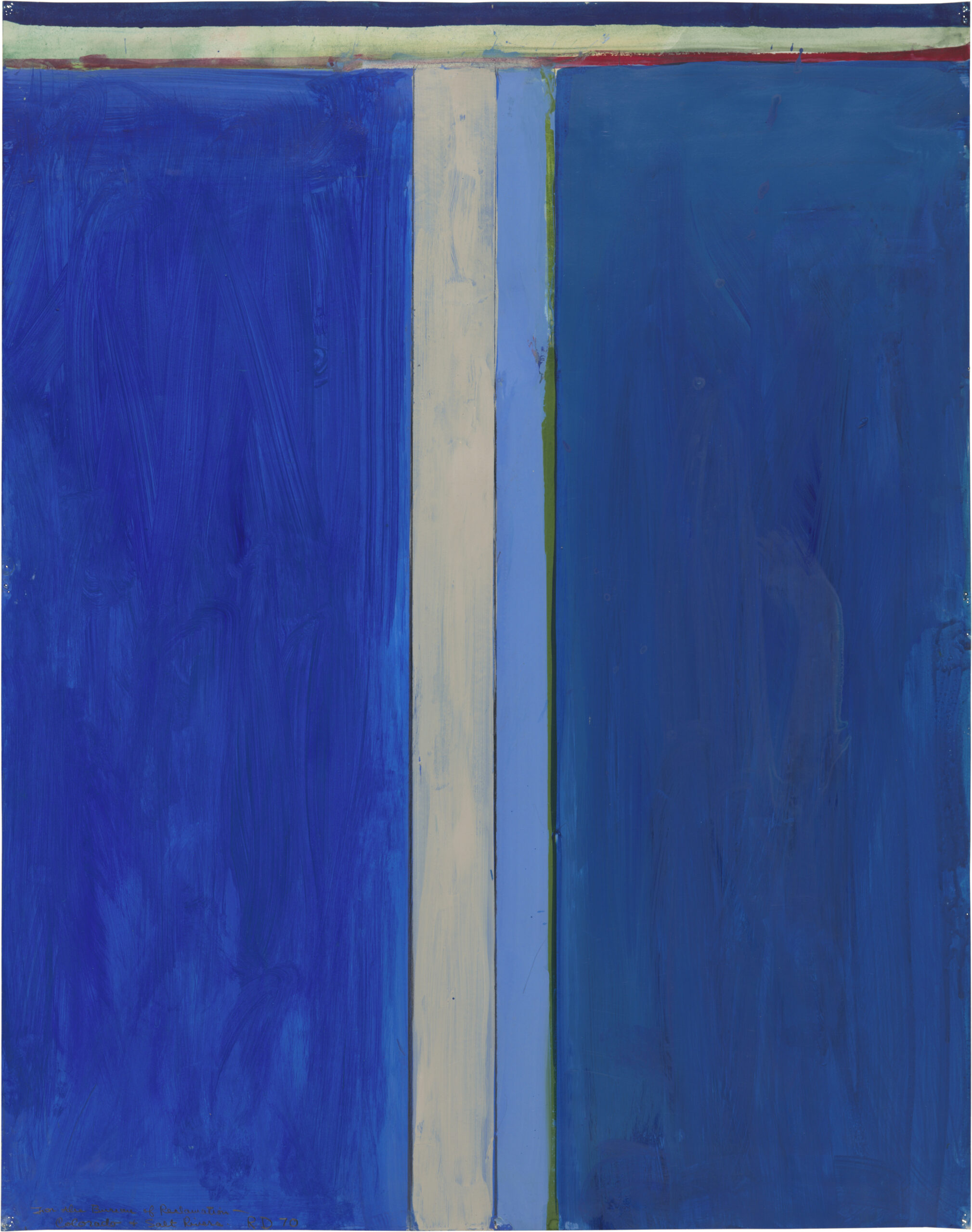

If DeWitt had seen Diebenkorn’s most recent paintings, he probably would have understood why the artist’s interest was piqued. By 1970 Diebenkorn had been working on his Ocean Park abstractions for about three years. This series marked a departure from the figurative style that he had pursued in Berkeley and embraced a new style of abstraction that relied on layered bands of color, unwavering charcoal lines, and translucent brushstrokes. He worked on oversized canvases, stretched to the edges of his body frame, and broke up their compositions into several smaller blocks of color that both pushed against each other and worked together to build a coherent balance. During this period, most of his paintings featured brilliant blues, pinks, oranges, greens, and yellows. These hues are often juxtaposed against cool slate blues. While not representational works by any means, these paintings were informed by the artist’s surroundings—the Ocean Park neighborhood of Santa Monica—and speak to the coastal marine layer of fog in the early morning, soft sunlight in the afternoon, and crisp ocean breeze of the evening.

Interested in the opportunity, Diebenkorn replied to DeWitt’s inquiry with a phone call, during which he expressed his reservations about entering into what was essentially a commission agreement. He always believed strongly in creating art for himself, based on his own aesthetic preferences, and only when sufficiently inspired to do so. As his daughter, Gretchen, once said of him, “…he didn’t paint what others wanted him to paint—only what he felt moved to paint.”4 In a follow-up letter, DeWitt confirms that he changed the wording in the contract to quell Diebenkorn’s hesitation: “I added this sentence to the contract I will show you when we meet: ‘It is understood that if the artist decides he is unable to complete any paintings that satisfactorily express his reactions, in his own judgement [sic], to his subject matter, the only penalty is that he will receive no honorarium above his travel and living expenses during the time he has visited the project areas’.”5

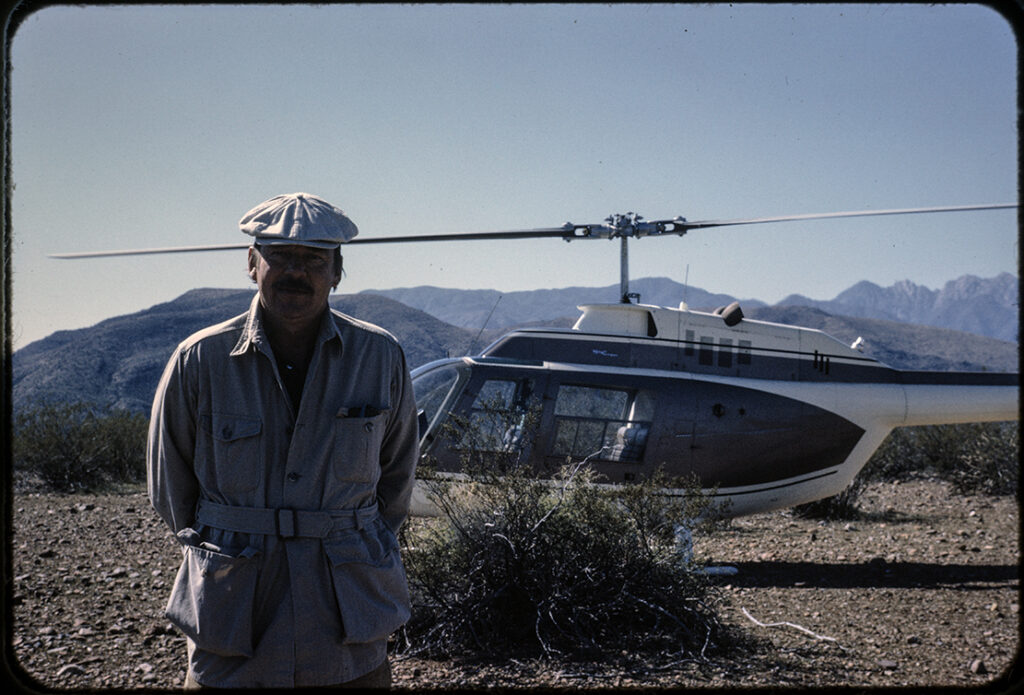

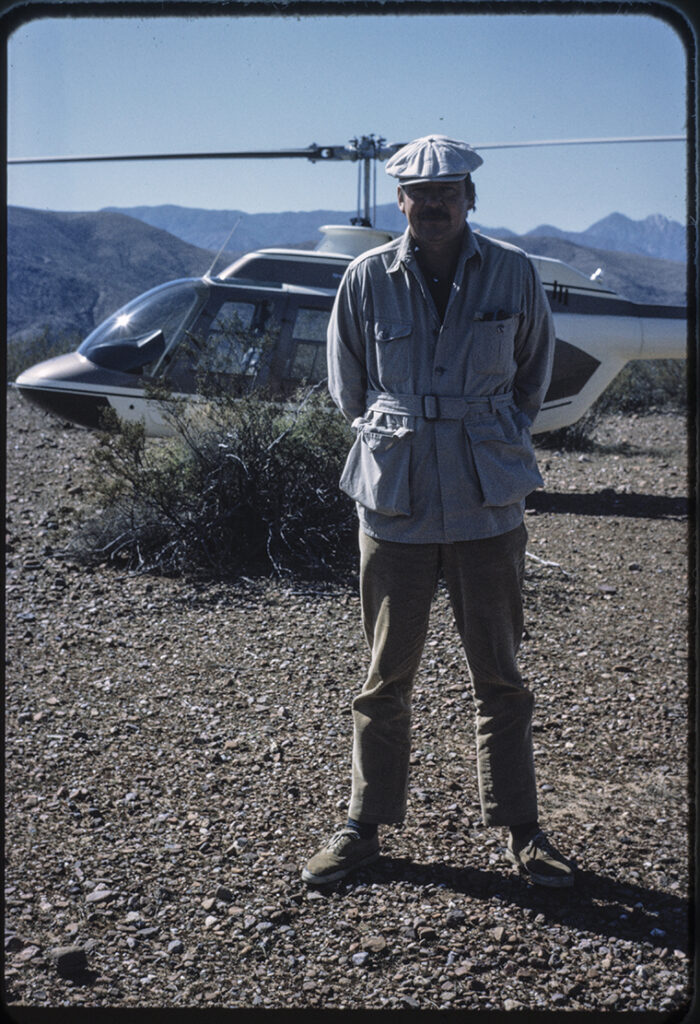

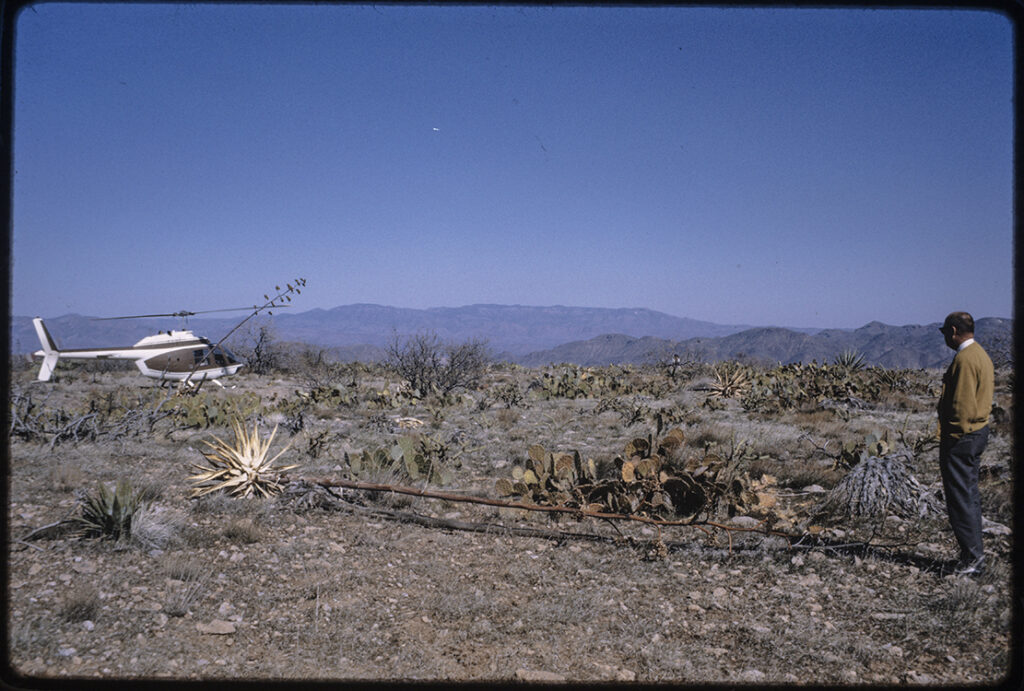

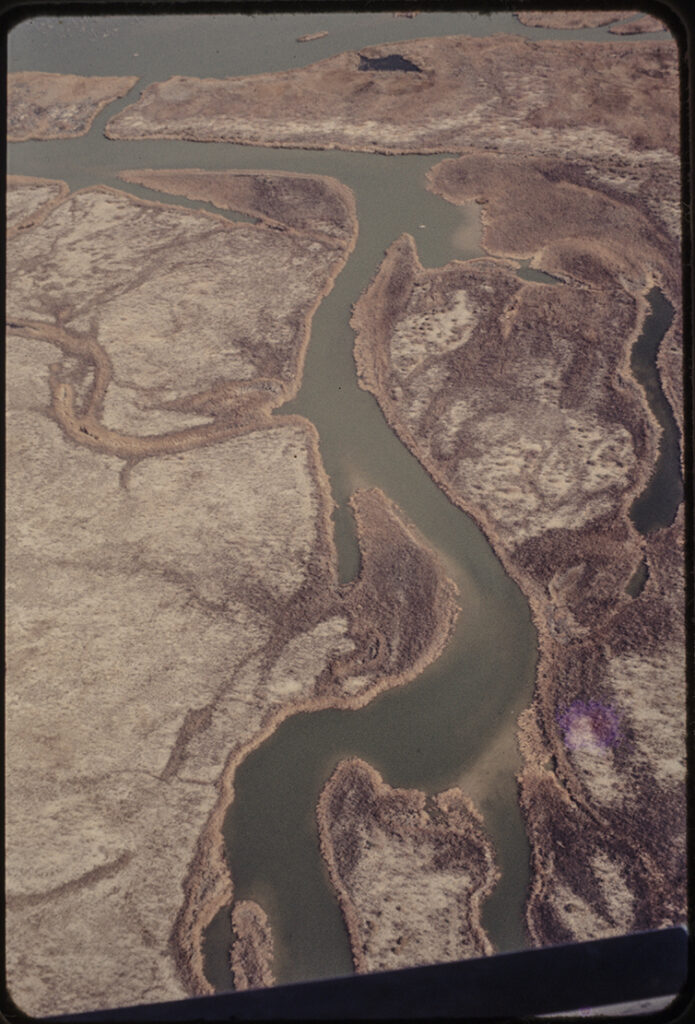

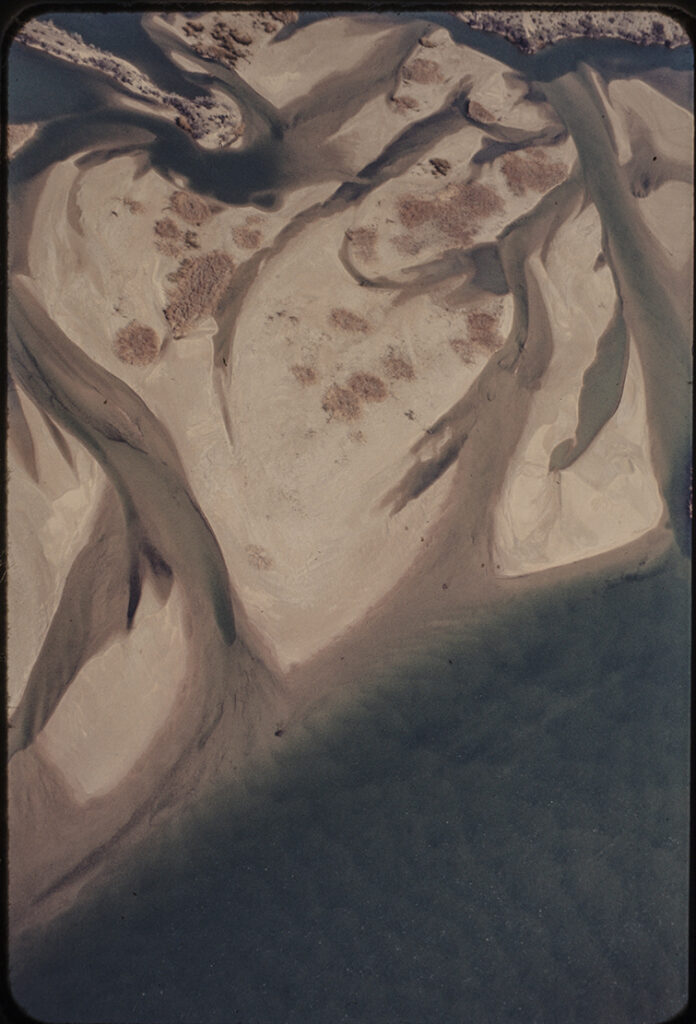

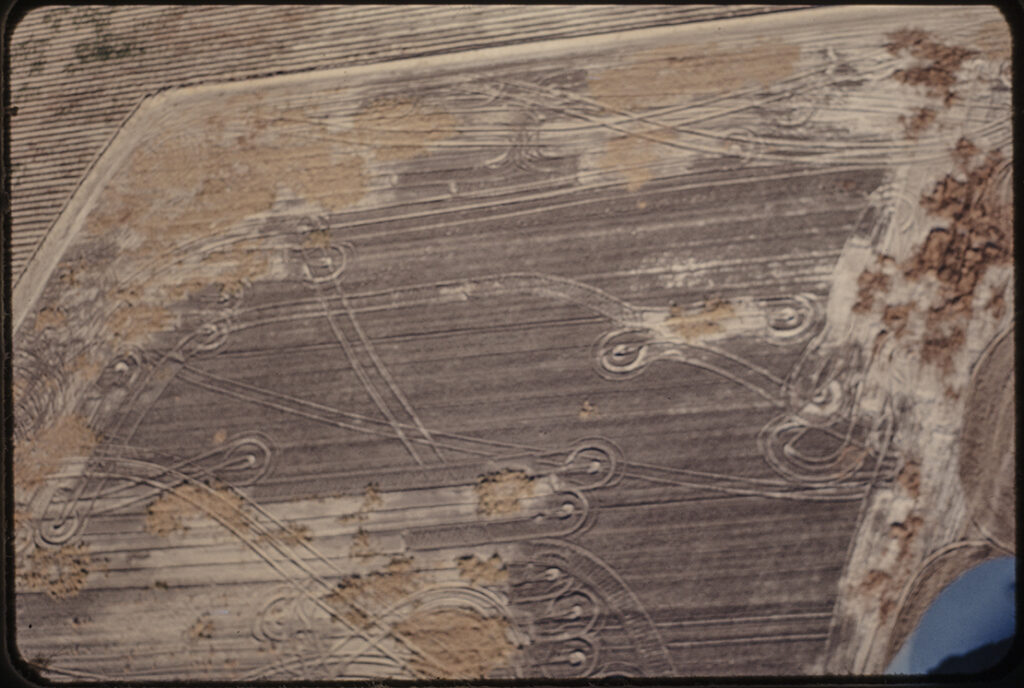

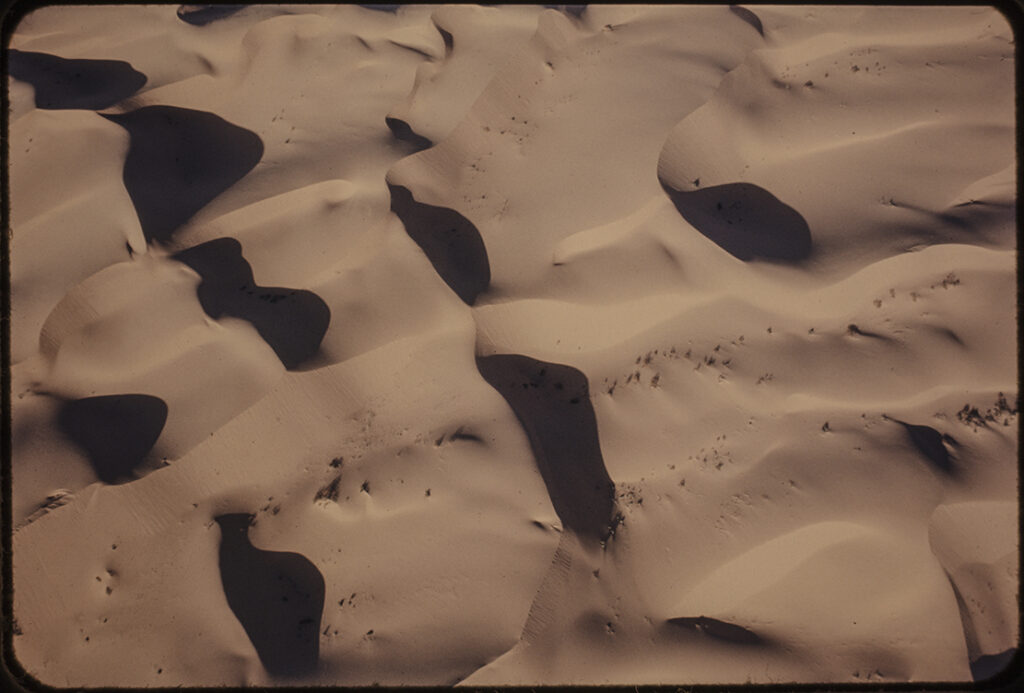

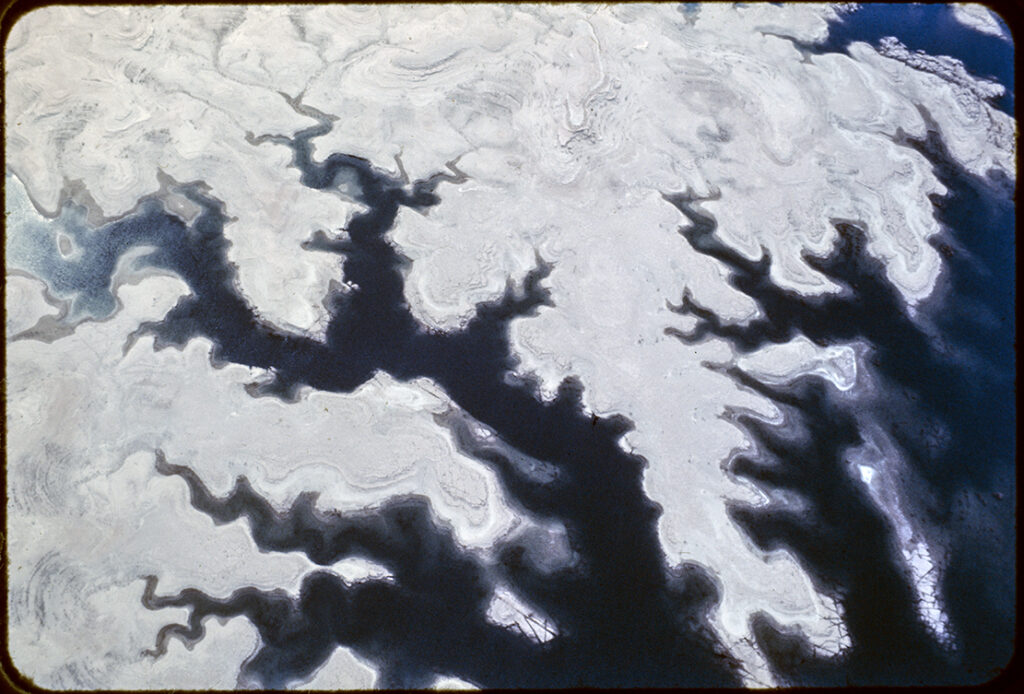

On February 15th, 1970, Diebenkorn joined fellow artists Kenneth Callahan, Chen Chi, and Eugene Kingman in Las Vegas to begin the five day aerial tour of the American Southwest. For Diebenkorn, this was an opportunity to reconnect with the vast and open spaces in which he was immersed during the few years he lived in Albuquerque in the early 1950s.6 His recent endeavors working in a new abstract vocabulary gave him a fresh perspective on the desert landscape, and the aerial views allowed him to see it as a never-ending expanse. As Time magazine would later describe, “The landscape was flat, almost a stretched canvas: pages and planes of earth, cross-cut by long ditches.”7 While in the air, Diebenkorn took several photographs of the land below, snapping images showing his particular interest in the relationships between land and water, especially soil patterns created during agricultural fieldwork.

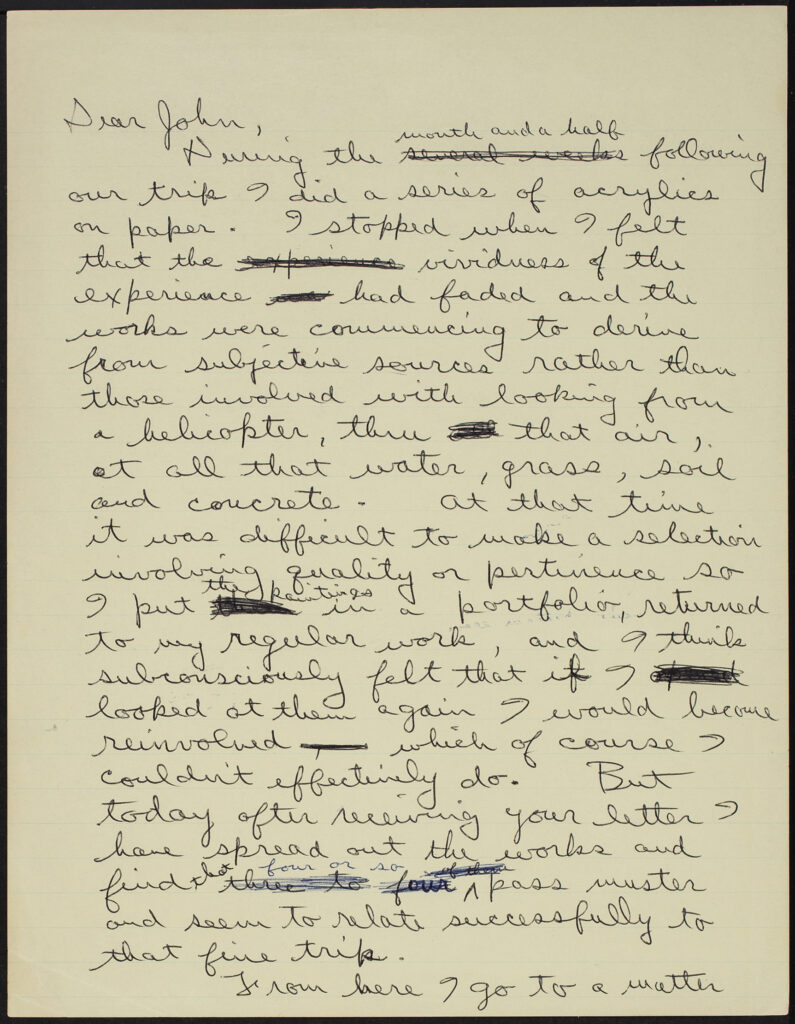

Over the course of the five-day helicopter trip, Diebenkorn began a group of paintings on paper, continuing to rework them for a time until “the vividness of the experience” began to fade, and he felt they were non-subjective reflections of “looking from a helicopter, thru that air, at all that water, grass, soil and concrete.”8 He filed these works away in a portfolio and moved on to other projects until, in 1971, DeWitt sent him another letter asking for an update on how the works had been progressing. DeWitt also detailed his plans for a forthcoming exhibition on the art created through the government program at the National Gallery of Art. In this letter, DeWitt was clear that he was not trying to rush the artist nor presume that any of the produced works would be deemed acceptable. Through a combination of DeWitt’s understanding of the artist’s process and the additional wording inserted to their contract, Diebenkorn had the flexibility to put his works aside until he could view them again with fresh eyes and be satisfied with the group as a whole. As he explained in a 1955 letter to Elinor Poindexter (the artist’s first New York dealer who represented his work for over fifteen years), “All I can expect are more fits and starts when I find myself painting at individual pictures. Then when I feel some sense of completion in terms of a group of pictures and a decent time span I’d like to show them…I can’t break up my work in order to sell some pictures now. And as much as I’d like to oblige you—do you a favor—the price in terms of my ‘working’ piece of mind is too high.”9 His friend Tony Berlant later recounted during the Ocean Park years that Diebenkorn “missed the old days when he could wait two years before he exhibited those works he considered done. He wanted to live with them before releasing them out into the world, something that had changed, thanks to increased demand from galleries.”10

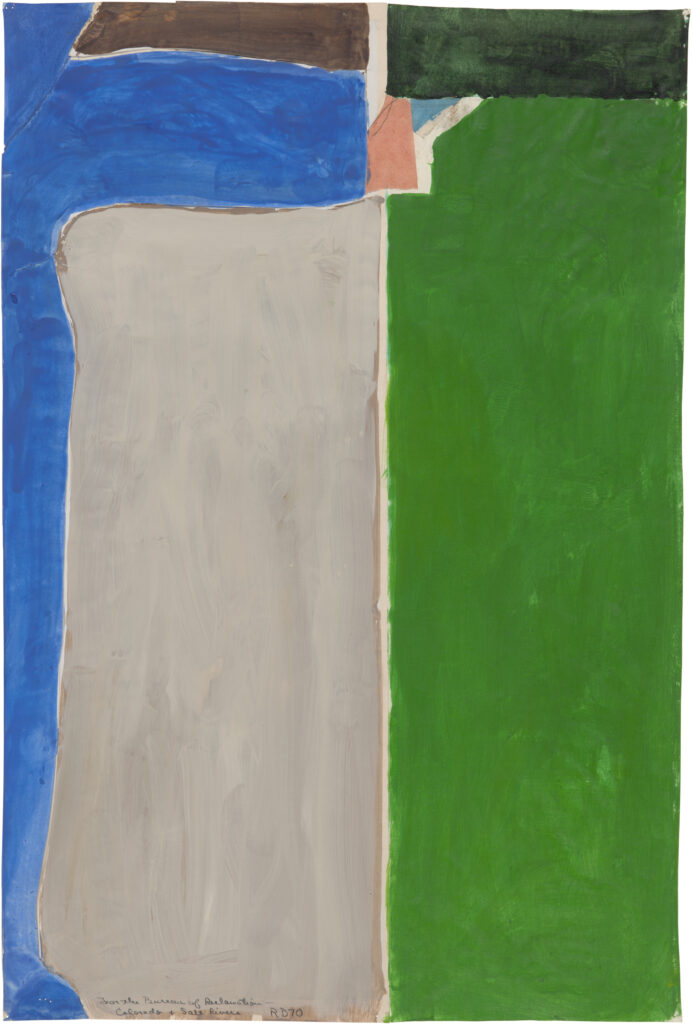

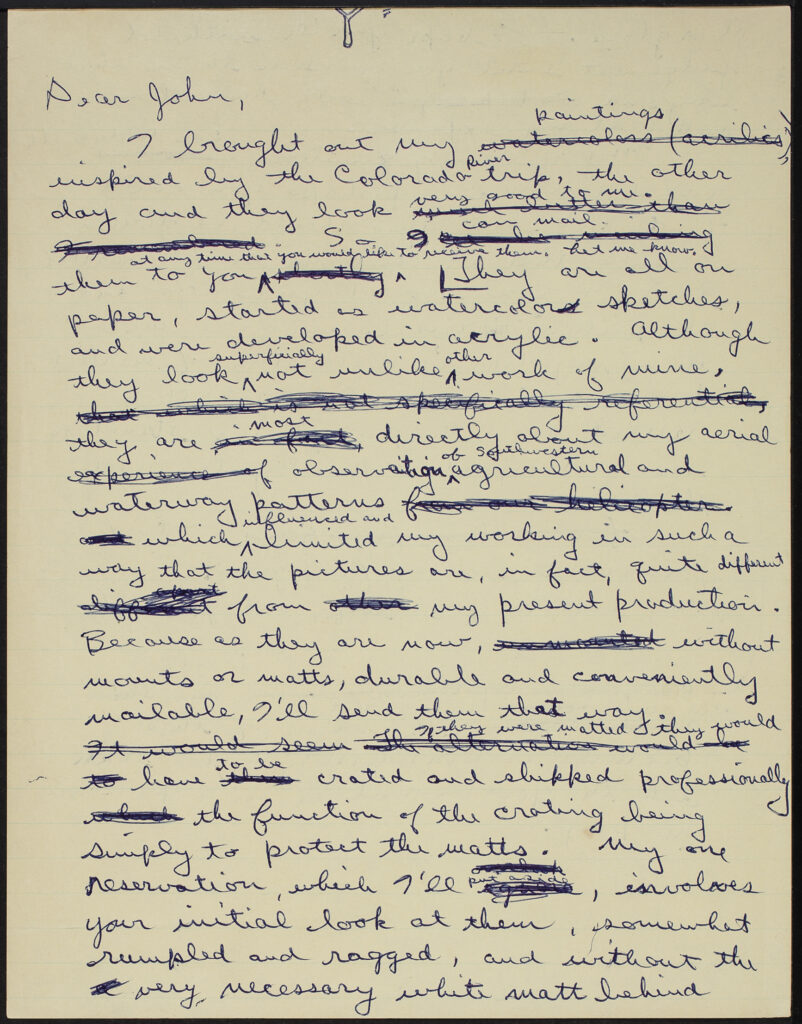

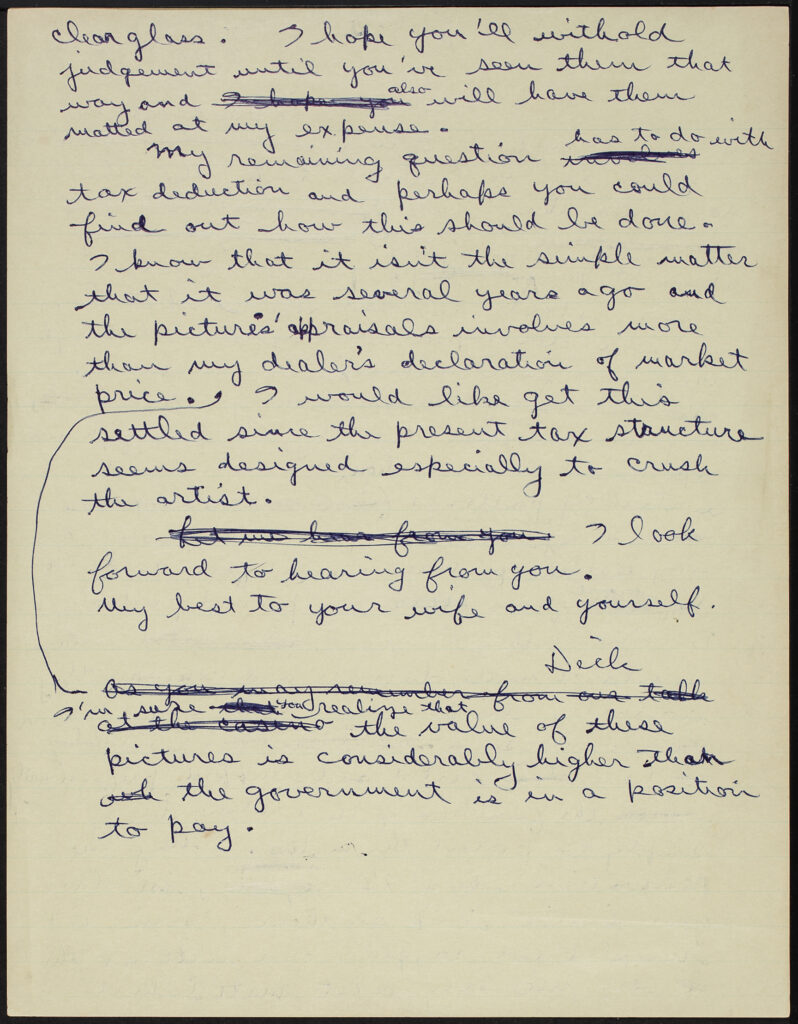

After receiving DeWitt’s inquiry in 1971, Diebenkorn revisited the works he had started during the trip and found eight that satisfied his aesthetic preferences, naming them Lower Colorado #1–8. While overall he scoffed at labeling his Ocean Park series as “abstract landscapes,” he confirmed that these works were created as interpretations of the landscape as seen during the five-day helicopter journey: “Although they look superficially not unlike other work of mine, they are most directly about my aerial observation of Southwestern agricultural and waterway patterns which influenced and limited my working in such a way that the pictures are, in fact, quite different from my present production.”11

While some of Diebenkorn’s contemporaneous Ocean Park compositions feature similar geometric grids, the Lower Colorado paintings on paper specifically evoke views of land and water, bringing life to an arid atmosphere. Deep river blues cut through dark browns and tans suggestive of compact soil, loose sand, or tilled earth. The artist remarked of the experience, “I think the many paths, or pathlike bands, in my paintings may have something to do with this experience, especially in that wherever there was agriculture going on you could see process—ghosts of former tilled fields, patches of land being eroded. I also saw large areas where the fields were all planted in the same way for the same crop yet showed unlimited visual variety. It boggled me! There was also circular farming: you could see clusters of concentric circles…but they were cut in so many different ways that each was unique, surprising.”12 Additionally, there are fewer colors within a Lower Colorado composition than in other Ocean Park works, and the color blocks are large, expansive, and channel the openness of the desert landscape.

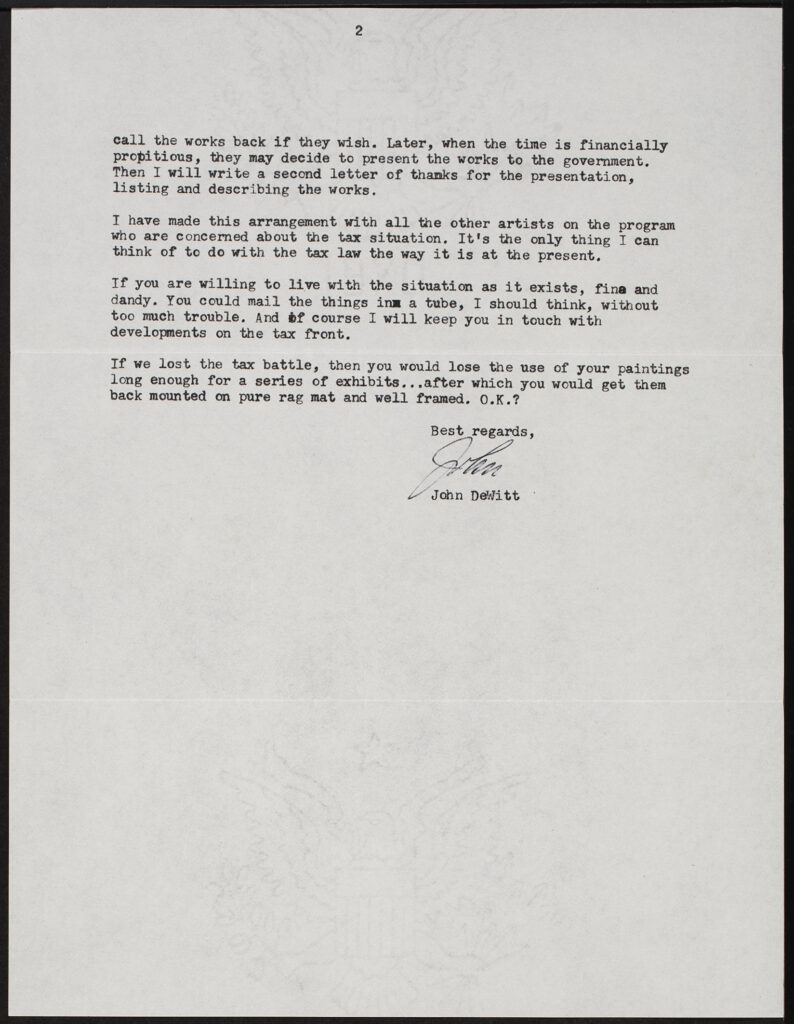

In 1971, Diebenkorn sent all eight of these works to the Bureau of Reclamation, and, after negotiating compensation for the works and discussing the impact of the new tax law preventing artists from receiving tax deductions for donated work,13 they were added to the Department of the Interior’s permanent collection. In 1972, John DeWitt’s eagerly anticipated exhibition, The American Artist and Water Reclamation, opened at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. The show highlighted a selection of artworks created through the program by the roughly forty participating artists, including Lower Colorado #1, #2, #3, #7, and #8. The catalogue featured an essay written by Douglas MacAgy of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden that would open to the public in 1974, in which he compared the exhibition to a play that invoked a spirit of wanderlust and curiosity, connecting the artists and their works to a broader American psyche.14 For a government-funded project supporting the arts, the show was well-received, and it traveled across the country to several other venues, including ones in Tennessee, South Dakota, California, and Texas.

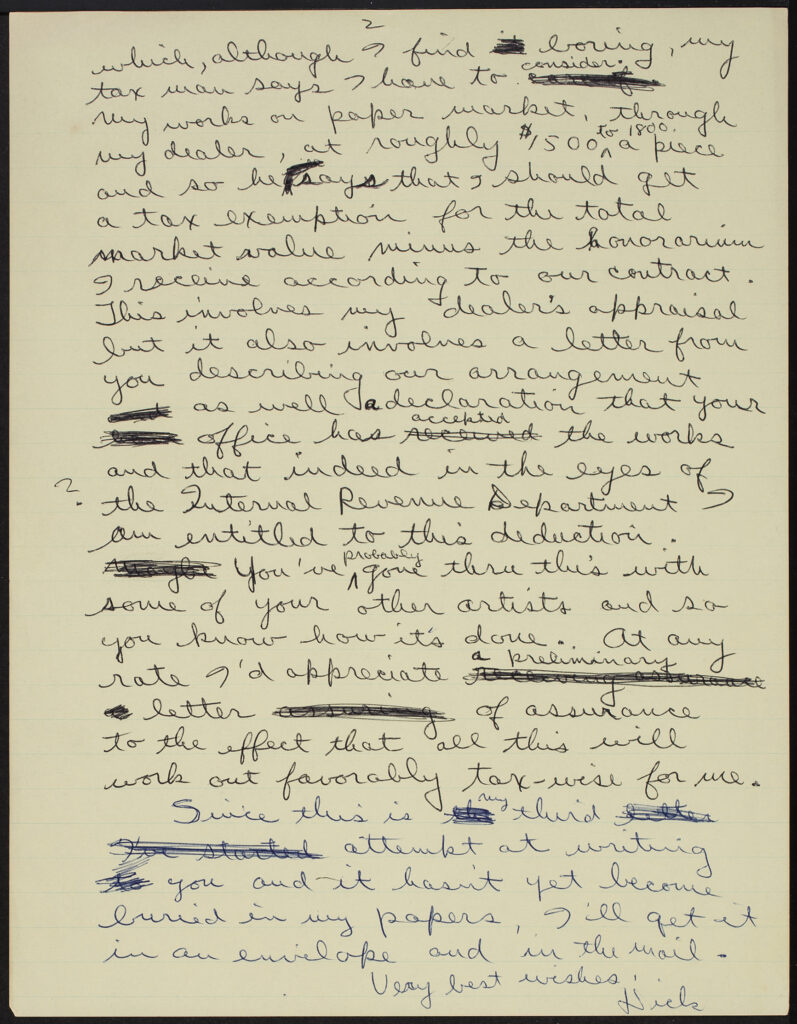

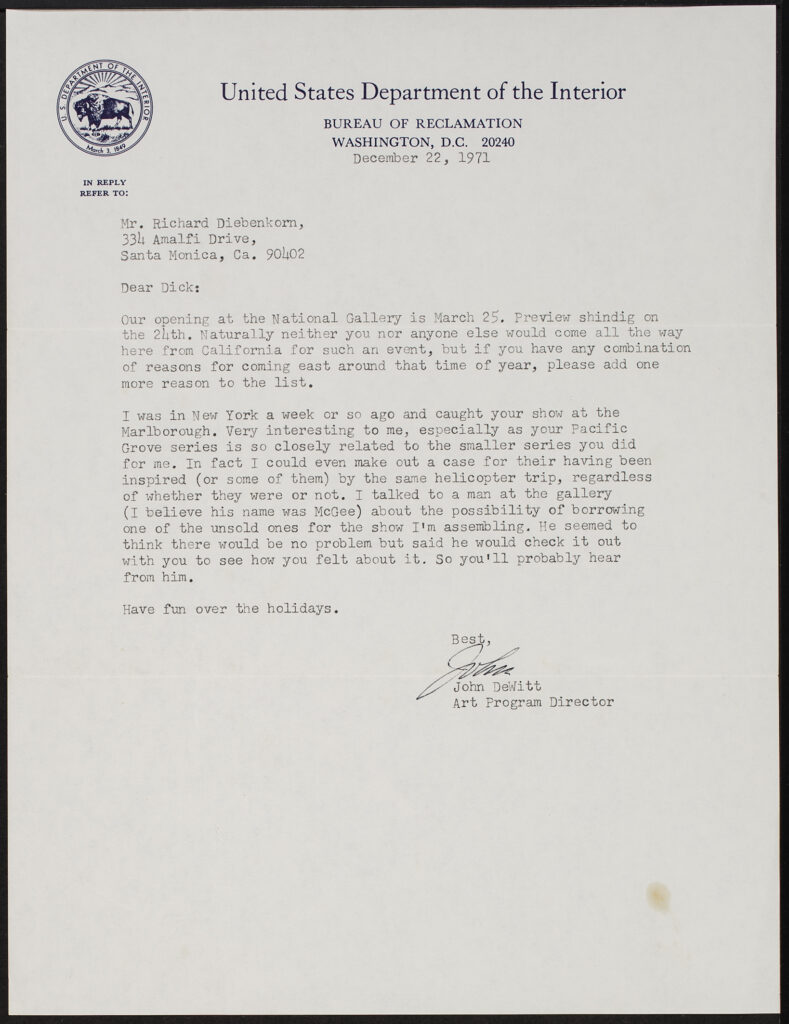

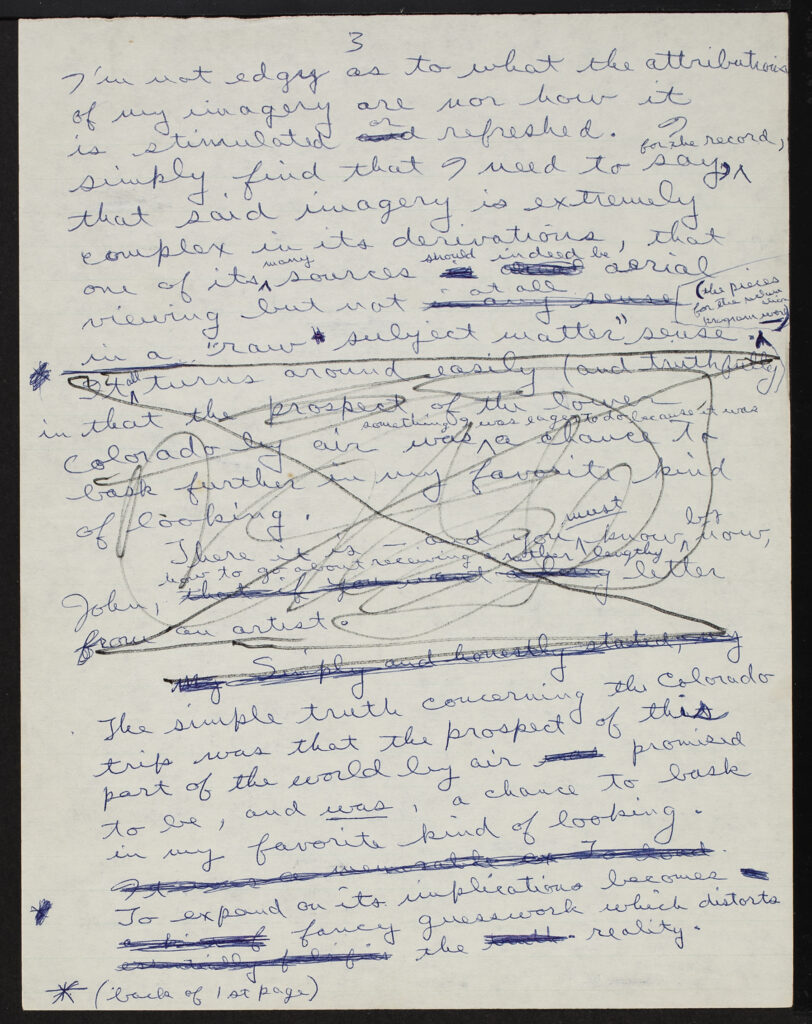

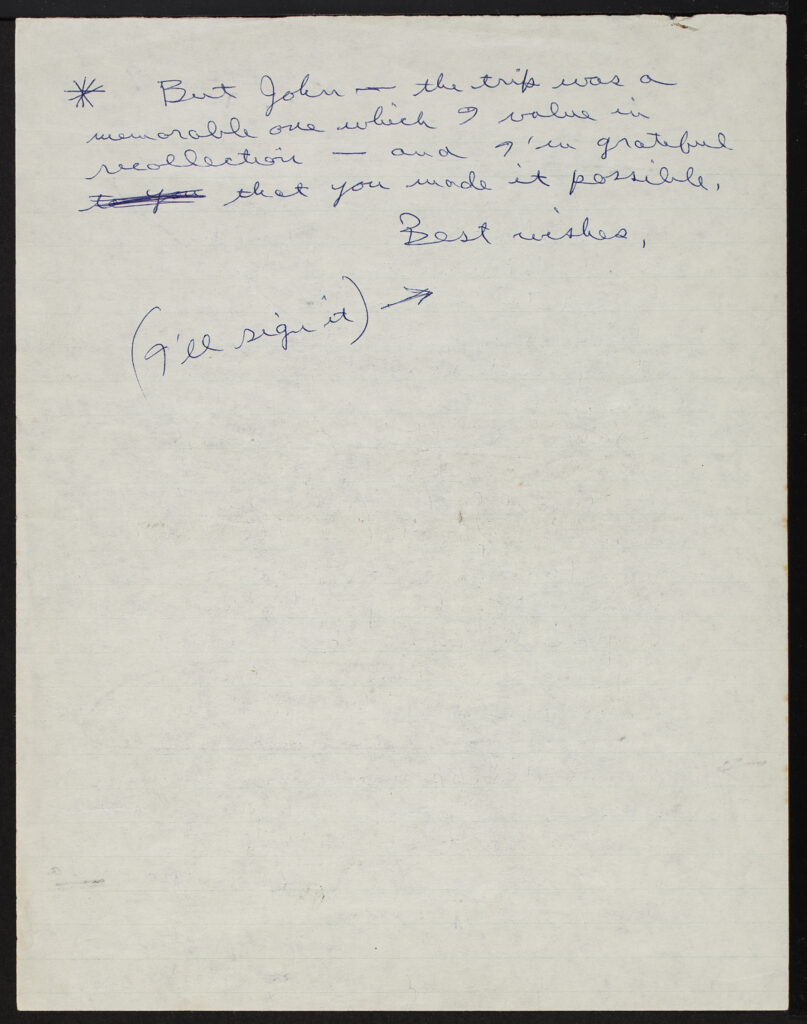

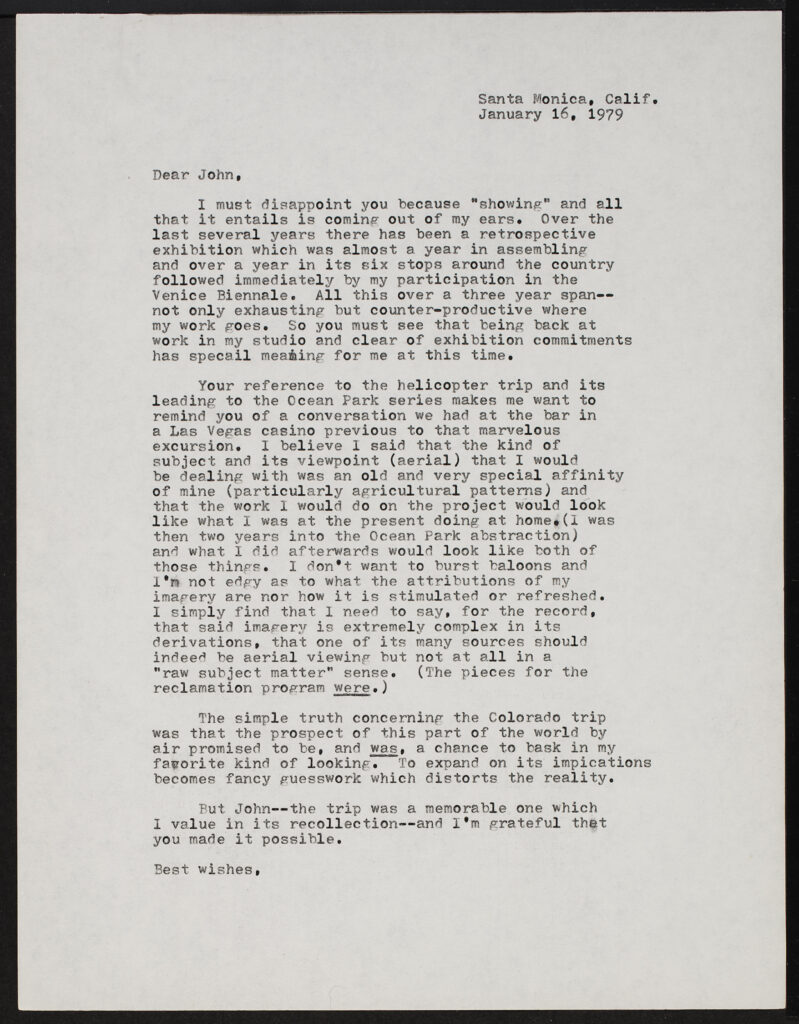

John DeWitt was proud of the project and the success it garnered across the country. He was especially impressed with the work that Diebenkorn produced for the Bureau of Reclamation, and in December of 1971, he sent a letter to the artist remarking on a selection of Ocean Park paintings that he had seen at Marlborough Gallery in New York, saying he could “make out a case for their having been inspired (or some of them) by the same helicopter trip, regardless of whether they were or not.”15 He made a brief mention of borrowing some of the works that were being shown by the gallery for an exhibition he intended to assemble, but offered no other details. Six years later, on December 5th, 1978, DeWitt sent another letter to Diebenkorn (transcribed at the opening of this essay) elaborating on this idea for an exhibition, which he wanted to call The Bridge to Ocean Park. Based on this sequence of letters, DeWitt may have been planning this show in his head for years, surmising that the helicopter trip was the sole event that launched Diebenkorn into his Ocean Park period, the artist’s most acclaimed and distinct body of work of his career. On January 16th, 1979, Diebenkorn responded to DeWitt’s inquiry with a carefully worded letter, expressing his exhaustion with the number of his recent exhibitions and gently explaining that the assertion of his Ocean Park work being inspired entirely by the Bureau of Reclamation’s program was misleading.16 He ends the letter saying:

“I’m not edgy as to what the attributions of my imagery are nor how it is stimulated or refreshed. I simply find that I need to say, for the record, that said imagery is extremely complex in its derivations, that one of its many sources should indeed be aerial viewing but not at all in a ‘raw subject matter’ sense. (The pieces for the reclamation program were.)

“The simple truth concerning the Colorado trip was that the prospect of this part of the world by air promised to be, and was, a chance to bask in my favorite kind of looking. To expand on its implications becomes fancy guesswork which distorts the reality.

“But John — the trip was a memorable one which I value in its recollection—and I’m grateful that you made it possible.”17

1. For a full list of artists who participated in this program, as well as artworks retained by the Bureau of Reclamation, see the Bureau of Reclamation website at https://www.usbr.gov/museumproperty/art/homepage.html.

2. John DeWitt, letter to Richard Diebenkorn, January 6, 1970, Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives, rdfa_1c1_b01_f17_i03_01.

3. DeWitt to Diebenkorn, January 6, 1970, rdfa_1c1_b01_f17_i03_01.

4. Gretchen Diebenkorn Grant, “Life and Art of her Father” (lecture, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, 21 June, 2013).

5. John DeWitt, letter to Richard Diebenkorn, January 21, 1970, Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives, rdfa_1c1_b01_f17_i06_01.

6. Some of Diebenkorn’s earlier work in abstraction was influenced by aerial perspective. In 1951, he took his first commercial flight, which flew low over the landscape. Speaking of it later, he said, “I’d never taken a plane trip like that before…It wasn’t that I went right to the canvas and said I’m going to paint this but it just went right into the mill and started coming out strong.” Mark Lavatelli, “Diebenkorn’s Albuquerque Years,” Richard Diebenkorn in New Mexico, 2007, 32.

7. Robert Hughes, “California in Eupeptic Color,” Time, June 27, 1977, 58.

8. Richard Diebenkorn, letter to John DeWitt, c. 1971, Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives, rdfa_1c1_b01_f17_i02_01.

9. Richard Diebenkorn, letter to Elinor Poindexter, 1955, Poindexter Gallery Archives.

10. Tony Berlant, “Diebenkorn: The Genius Next Door,” Richard Diebenkorn: A Retrospective, 2019, 10.

11. Richard Diebenkorn, letter to John DeWitt, c. 1971, Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives, rdfa_1c1_b01_f17_i01_01.

12. Richard Diebenkorn quoted in Dan Hofstadter, “Almost Free of the Mirror,” New Yorker, September 7, 1987, 60–61.

13. The letters exchanged between Diebenkorn and DeWitt containing their tax discussions can be seen on diebenkorn.org. Tax law P.L. 91-172 (also known as the Tax Reform Act of 1969) came into effect on January 1, 1970, and limited the amount of money that artists could deduct on their taxes if they were donating their work to a public institution; they could only deduct the amount spent on materials, rather than the fair-market value of the work. This law remains in place today.

14. Douglas MacAgy was an influential figure in the American artistic sphere, and had first met Diebenkorn while serving as the director of the California School of Fine Arts in 1946.

15. John DeWitt, letter to Richard Diebenkorn, December 22, 1971, Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives, rdfa_1c1_b01_f17_i09_01.

16. The drafts of this letter can be seen in the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives.

17. Richard Diebenkorn, letter to John DeWitt, January 16, 1979, Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives, rdfa_1c1_b01_f17_i10_06.