An interview with Sasha Nicholas, author of “Everything All at Once: Richard Diebenkorn and Postwar American Art”

A new monograph debuts, Richard Diebenkorn: A Retrospective

September 17, 2019

New York, NY

This month, Rizzoli New York introduces Richard Diebenkorn: A Retrospective, the most comprehensive monograph yet on the distinguished American painter, draftsman, and printmaker for readers of all backgrounds and levels of interest.

The book features a fresh voice in art history, Sasha Nicholas, who brings the artist alive and anew in a fascinating and visual essay so that audiences are able to, as she says, understand the artist “not as a solitary figure working in isolation,” but rather, as a painter whose career is deeply connected to events in postwar America.

Diebenkorn.org recently spoke with Ms. Nicholas ahead of a reading she will give this month in New York to celebrate the new monograph.

What was your reaction when you were asked to write the essay?

I was thrilled of course, but you know, “No pressure!”

This was a very exciting challenge and very daunting. There have been a lot of terrific texts, such as Jane Livingston’s in the artist’s catalogue raisonné (Yale University Press, 2016), to the many monographs. I felt that I had to write something different, to look for a new approach to Diebenkorn and hopefully draw in a new audience.

You very vividly bring him to life on the page as an artist and a person. In fact, you remark early on that he “reinvented his aesthetic when it began to seem fashionable or effortless” and “was compelled by a deeply personal code of intertwined ethical and artistic convictions.”

I did not know Richard Diebenkorn, but I tried to capture, as best I could, his tenacious, perfectionistic, and strong willed personality and how it informed the work. He himself tended to be reticent when it came to his art. He did not want to be pinned down, so he let the work stand for itself. He did not want to be fashionable. He was an independent spirit. The idea of an art that was very calculated and avant-garde was antithetical to the person he was.

Throughout the essay, you talk about the tension between abstraction and representation, and as you write, his “insisting on multiple ways of seeing” which ensured that his work “transcended its historical moment.”

Richard Diebenkorn evaded easy classification. He was multifarious and a shape shifter. Very few artists moved across the spectrum of aesthetic approaches as fluidly as he did. By constantly challenging himself in this way, he made sure his art never felt dated or mechanical in any way. It was always fresh.

His “risky and startlingly fluid movement” between these modes occurred in a time of heated arguments in the art world and his nonconformism, as you assert, “sometimes landed his work in the margins of postwar histories.” What was happening in the 1950s, and why was that important for you to convey to the reader?

His “risky and startlingly fluid movement” between these modes occurred in a time of heated arguments in the art world and his nonconformism, as you assert, “sometimes landed his work in the margins of postwar histories.” What was happening in the 1950s, and why was that important for you to convey to the reader?

Richard Diebenkorn came of age as an artist in a time when there was tremendous pressure to embrace abstraction. It is easy to lose sight of how radical it was for him, at the apex of his great success with his abstractions in the 1940s and ‘50s, to abruptly do something different, shifting to a painterly representational style, focusing on figures, Bay Area landscapes, and still lifes. It was a very bold move to reinvent himself, especially so early in his career. I find it incredibly inspiring. Many of us want to reinvent ourselves in such a bold way, but it’s very difficult to do.

You make the point that although he was always independent and “shied away from Abstract Expressionism’s heroic claims,” he was influenced by key members of the AbEx movement, and yet he said he was “really a traditional painter, not avant-garde

at all.”

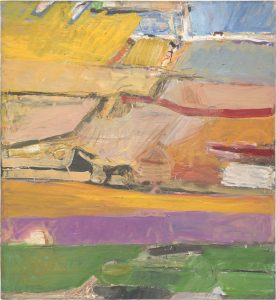

Richard Diebenkorn looked really hard at Abstract Expressionist painting, as so many did in his generation. Clyfford Still (d. 1980) was especially important, and Diebenkorn’s early palette was inspired by him. There was an Arshile Gorky (d. 1948) retrospective that he saw very early on, and he emulated the artist’s calligraphy and turbulent brushwork. It is not coincidental that he met Willem de Kooning (d. 1997) just before he began the Berkeley paintings, and his paintings then became very ambitious and gestural. But although he was stimulated by these artists, he never imitated. He transformed what he saw into his own vision, such as Berkeley #52, 1955, with its open areas of lush, broadly swept color. The formal and chromatic ambition of works like this one earned him a place in major exhibitions and recognition by critics, like AbEx chief theorist Clement Greenberg.

Let’s turn to your theme of the artist’s search for “rightness,” which he himself mentioned in his studio notes and interviews, and of course in his remark in 1986 to John Gruen that, “Now, the idea is to get everything right—it’s not just color or form or space, or line—it’s everything all at once,” that would famously become the title of Gruen’s article for ARTnews.

I actually struggled with this notion of “rightness,” which sounds dogmatic, and of course Richard Diebenkorn typically reacted against dogma. It was a very personal idea: how a work would achieve rightness. It meant to him, in part, that his work needed to be hard fought. He had been convinced by his close friend and fellow Bay Area artist David Park (d. 1960) that art should be hard-hitting, even coarse and awkward at times. Park called paintings like this “troublesome pictures.” Diebenkorn’s sense of rightness was bound up with his art not being easy. This was an ethical position for him.

Throughout the essay, you situate the artist and the work he was making within the particular time in postwar America, such as the contemporary art scene in Los Angeles in the 1960s, where he was exhibiting alongside Light and Space artists and, as you write, “the sleek, hard-edge Finnish Fettish epitomized by [Larry] Bell’s (b. 1939) crystalline glass boxes or [Craig] Kauffman’s (d. 2010) plastic wall sculptures.”

Of course, the move to Los Angeles did transform Diebenkorn. We think about his shift to the Ocean Park paintings at this time as relating to the landscape, to Santa Monica, to the industrial geometry of his new studio there, and to the very bright, Southern California light. While these factors were essential, I think it’s valuable to remember he was working in a neighborhood populated by revolutionary artists. A lot of the artists there were thinking about the same kinds of issues. Light and Space was about the work of art not being just a thing, it was about how our vision works in relation to that work of art, how we move around it, how a work of art interacts with the environment it’s in. I wanted to think about Diebenkorn’s Ocean Parks in dialogue with those issues as well.

Your essay includes, literally, many radiant and sublime works, such as #22 (Albuquerque), 1951 and Untitled (Yellow Collage), 1966. Do we dare ask you to remark on a single work that for you expresses your feelings about the artist?

Woman in Profile, 1958. It operates on multiple levels, and there is that tension between abstraction and representation. If you took out the figure, you would almost have an Ocean Park, with that tapestry-like weave of geometry. There is that tension between this very expansive and serene, peaceful moment, which is also more than a bit eerie, with this isolated figure whose body is very much pushed against the canvas surface, penned in by the window mullions, and there is that intense, mask-like wash of light on her face.

In fact, you refer to the canvas Woman in Profile, 1958, as one of the most iconic of his representational oeuvre, belonging to a body of “monumental canvases depicting the figure in architectural settings, often with a view to the outdoors,” that recall the paintings of Edward Hopper (d. 1967), whose work we know Diebenkorn admired.

Richard Diebenkorn, like Hopper, captures these intangible moments that we all can relate to—the quiet moments we have to ourselves that we experience as solitude, which can be both serene and poignant. We feel ourselves in the works.

A note to news media and researchers: to request an interview with Sasha Nicholas, please email Brent Jones.

For more information, and to pre-order Richard Diebenkorn: A Retrospective, please visit Rizzoli.

Explore the title and talk with us on Instagram @diebenkornfoundation, @rizzolibooks, and @trifoliosrl.