Six on Sausalito

Six perspectives on artworks, people, places, and ideas that tell new stories about the Sausalito period and are preserved in the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives, Colby College Special Collections & Archives, and the Clyfford Still Archives

By Carl Schmitz

October 1, 2020

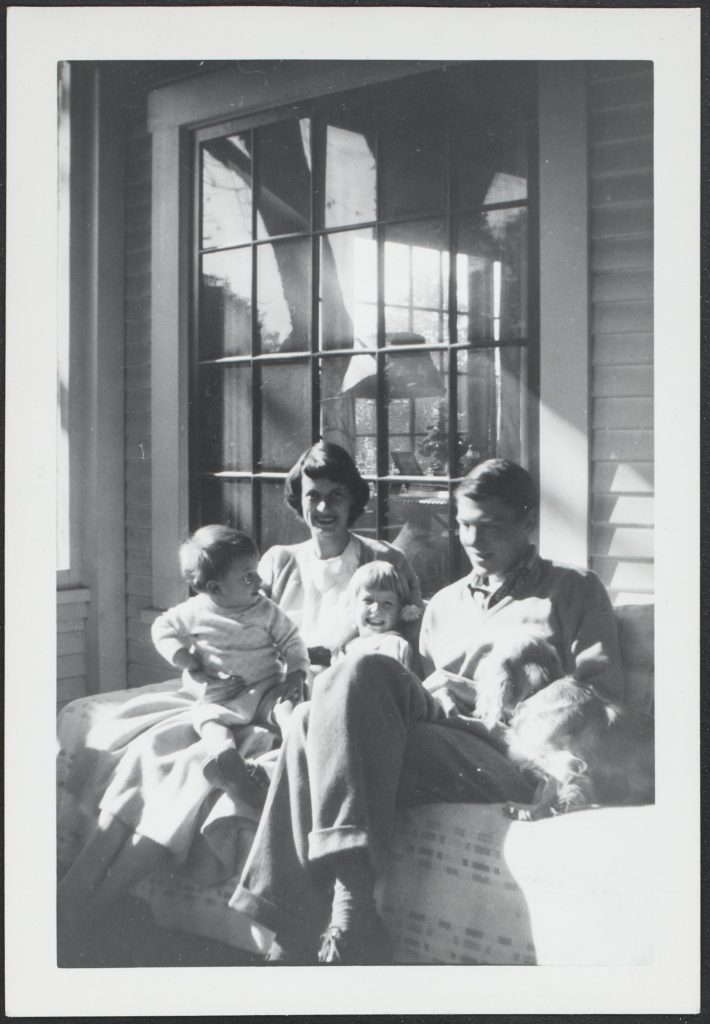

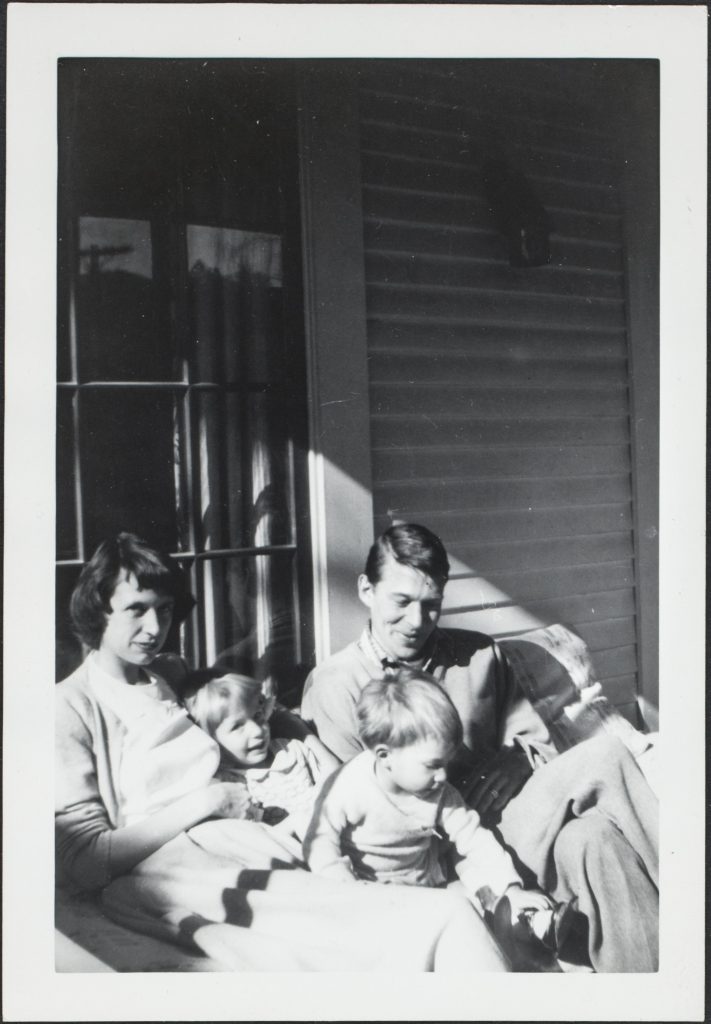

Before moving to Sausalito in the summer of 1947, Richard Diebenkorn and his family were separated by World War II during the artist’s military service, quartered together on a Marine Corps base, and stayed temporarily with extended family or in rentals. Although they would only spend two and a half years in Sausalito—located north of the Golden Gate Bridge, six miles from the heart of San Francisco—this period was significant for the young family. In Sausalito, Richard, his wife Phyllis, and their two children lived in the first home they could call their own.

The years in Sausalito were also critical for Richard Diebenkorn’s development as an artist. Until this time, Diebenkorn was considered “by far the most important among the group of painters in this area whose names are not yet well known,”1 and upon the Diebenkorn family’s departure from Sausalito in January of 1950, he was said to be “well known throughout this area for his bold interpretations in the contemporary manner.”2 The artwork itself is evidence of this emergence—Diebenkorn’s Sausalito paintings illustrate arguably the greatest change during a single period without an analogous shift in subject matter—and the Sausalito work is considered the artist’s first mature output accordingly (see examples Untitled (Sausalito #3), 1948, and Sausalito, 1949).

While seventy years have passed since the Diebenkorn family left Sausalito, the living history within archival collections allows for new perspectives on those transformative years. The value of preserving everyday ephemera, including newspaper clippings, letters, and exhibition announcements, may have been difficult for Diebenkorn and his family to anticipate at such an early point in the artist’s career. However, with the expansion of archival collections over three generations, this period of growth and change for Diebenkorn can now be more broadly contextualized. Surviving archival materials provide insight into the environment in which Richard Diebenkorn developed as a young artist and embarked on his first sustained Abstract Expressionist series. Here are “Six on Sausalito”: six perspectives on artworks, people, places, and ideas that tell new stories about the Sausalito period and are preserved in the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives, Colby College Special Collections & Archives, and the Clyfford Still Archives.

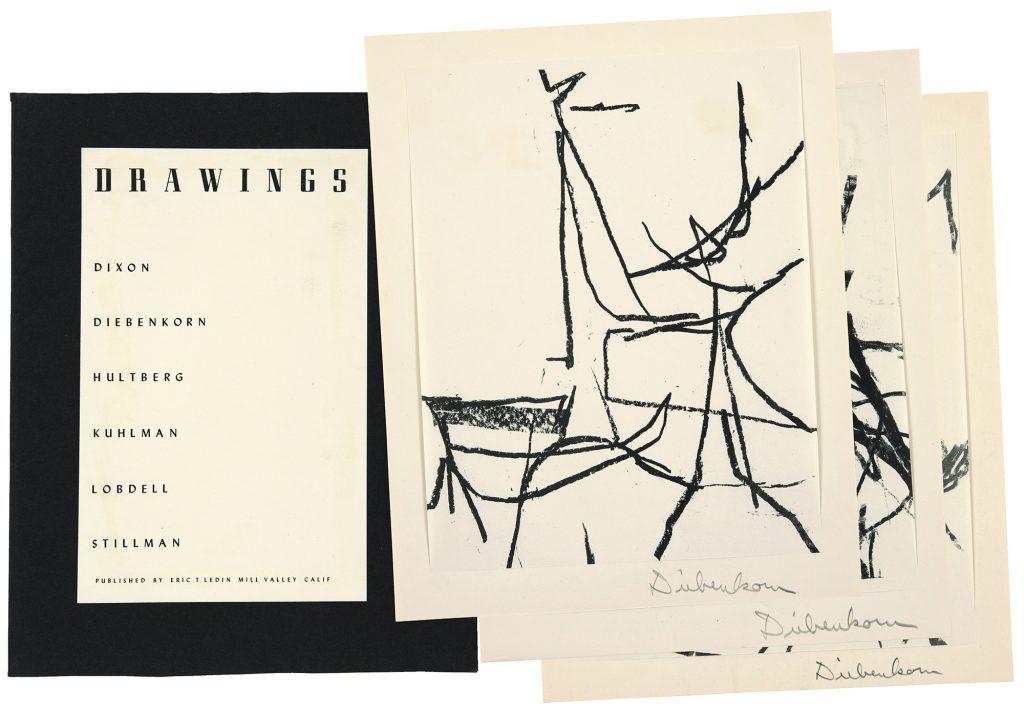

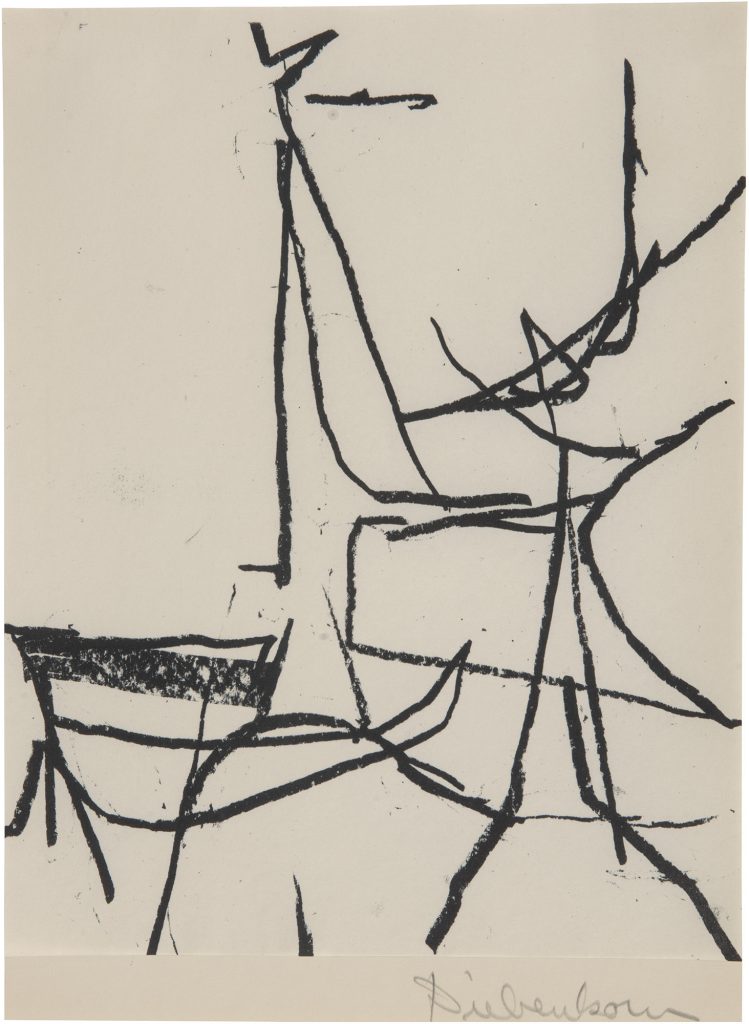

1. Drawings Made a Statement

Living in Sausalito was a practical and manageable choice for the Diebenkorns. The seaside town was close enough for a reasonable commute to the California School of Fine Arts (CSFA, now the San Francisco Art Institute) in San Francisco where the artist taught, yet far enough away from the city for them to better afford a home on the hillside just above Sausalito’s Bridgeway Promenade. Other CSFA artists and their families, including John Hultberg, Walter Kuhlman, and Frank Lobdell, also opted to live in Sausalito, and this modernist art colony has been credited as “Sausalito’s most important contribution to the history of art.”3

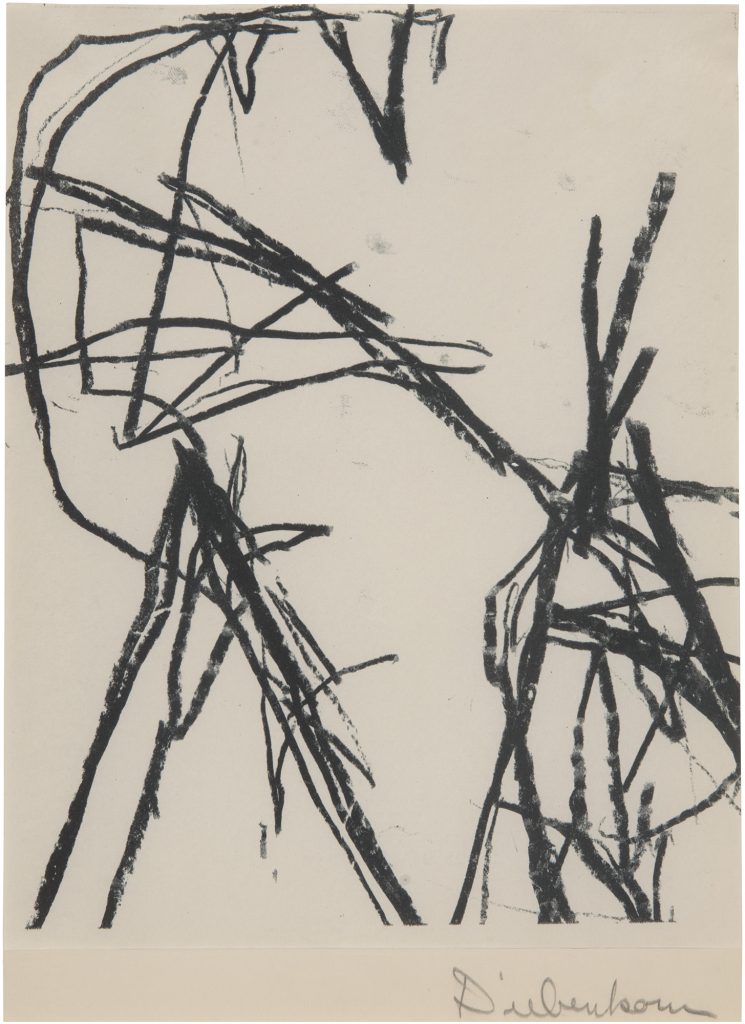

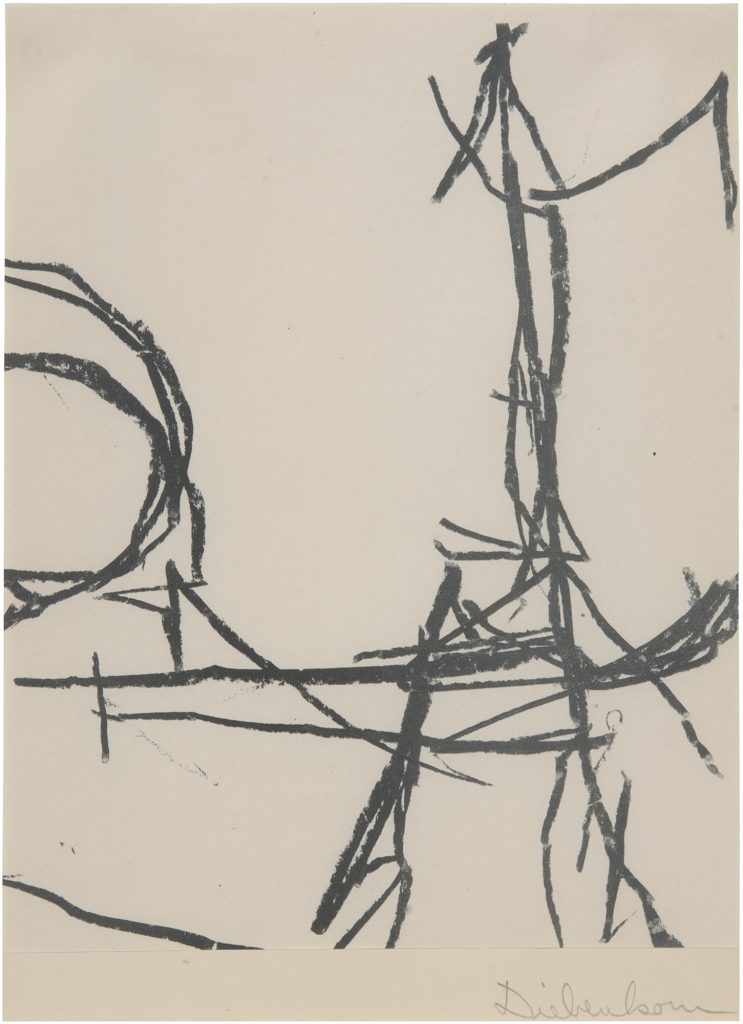

At the end of 1948, the Sausalitans, along with CSFA colleagues James Budd Dixon of San Francisco and George Stillman of Berkeley, collaborated on Drawings, a portfolio of sixteen or seventeen offset lithographs.4 Although they all worked with non-objective subject matter, they each took different approaches to the project and achieved distinctly individual results. As the first such group print portfolio, Drawings is a landmark in the early history of Abstract Expressionism and has been collected by museums as far away as the British Museum and the National Gallery of Australia.

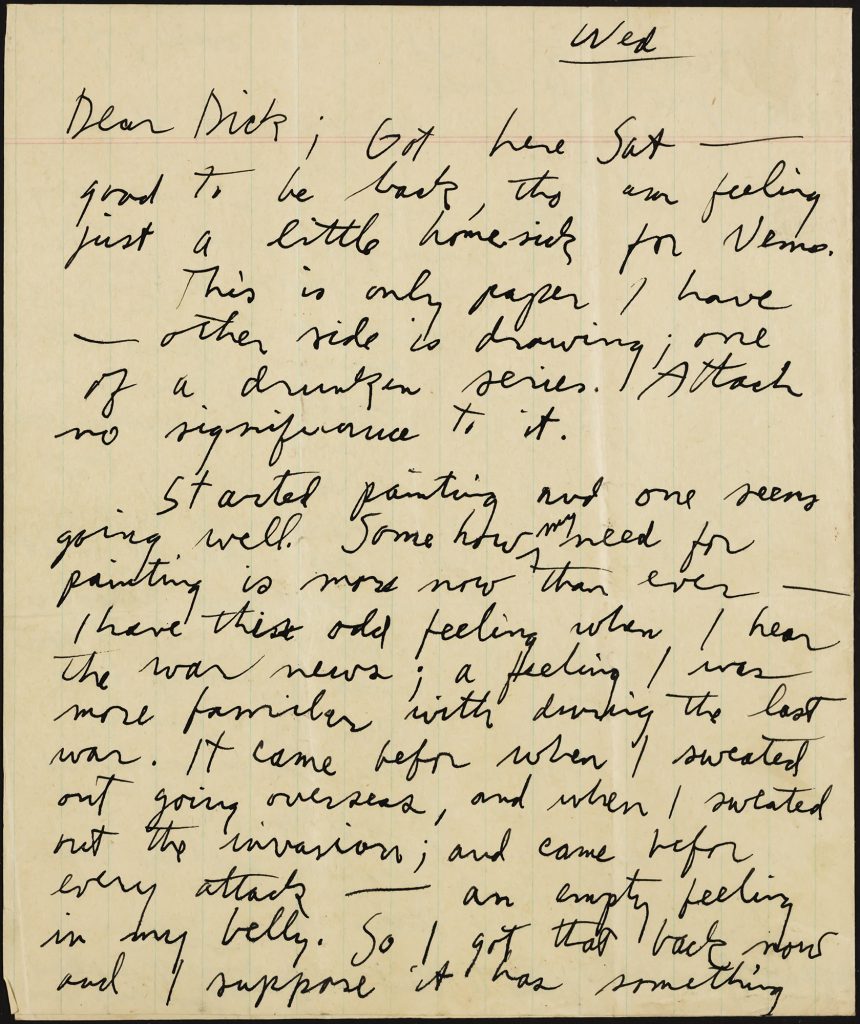

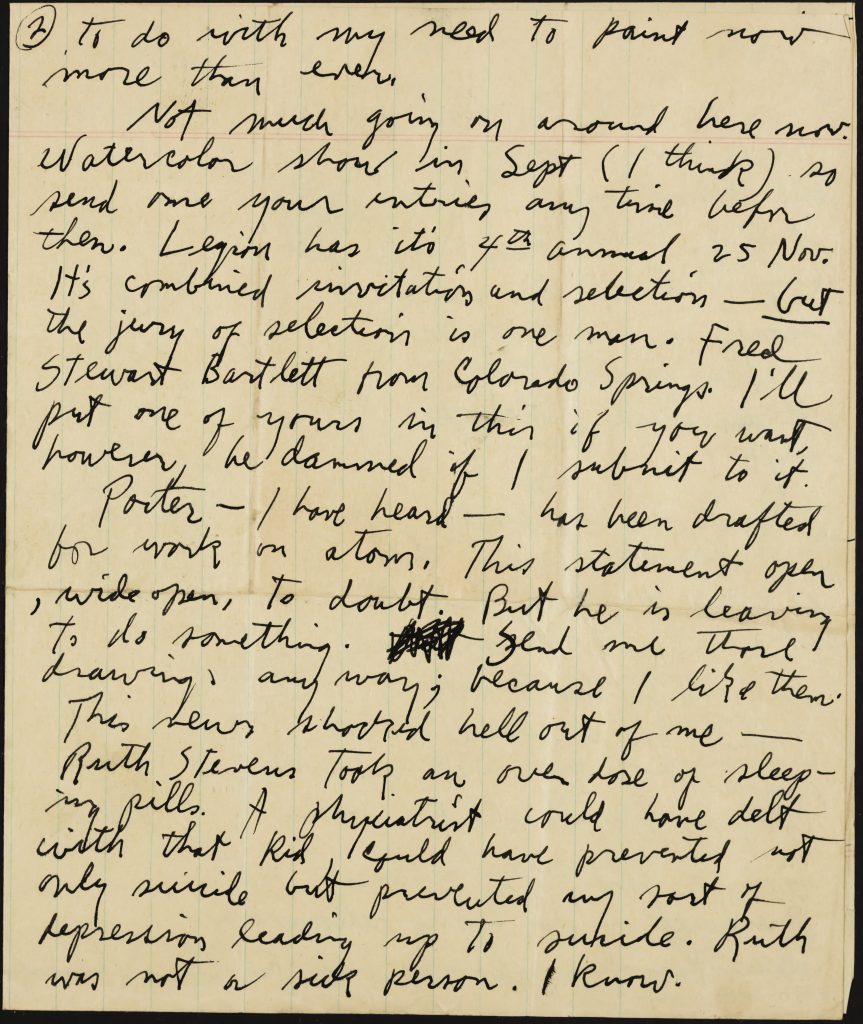

The portfolio is the most recognized work created by the Sausalito moderns—an informal group including artists Diebenkorn, Lobdell, Hultberg, Kuhlman, Dixon, and Stillman5—but what is known about it is still subject to discovery. Although it is often noted that the portfolios were sold for only a dollar, and even then sold very slowly (a story perhaps inspired by the underdeveloped art market in the Bay Area at the time), Richard Diebenkorn wrote in a letter to Phyllis: “The drawing portfolio was finished and is practically sold out. It is stunning and elegant looking and there have been nothing but compliments on it. Most people say it should have sold for $5 instead of $1.50.”6

2. Katharine Parker Set a Course

As one of the first supporters of modern and abstract art in Sausalito, Katharine Parker made a singular and thus far unrecognized contribution to the Sausalito modernist art colony. Parker was a curator at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco and taught weekend art classes at the museum alongside Lobdell. In the spring of 1949, she lived across the bay in downtown Sausalito and founded the Contemporary Gallery on the Bridgeway Promenade.

Organized by Parker, the Contemporary’s inaugural show was a comprehensive showcase that featured paintings, sculpture, ceramics, plastics, textiles, jewelry, furniture, and records.7 Among the painters, the show included all of the Sausalito moderns from the Drawings portfolio as well as two more of their CSFA colleagues, Edward Corbett of Point Richmond and George Abend of San Francisco. Within the following year, Parker moved to San Francisco and married Abend. The opening was Parker’s only full-scale exhibition at the Contemporary, although the gallery would carry on without its founder in the years to come.

3. Bern Porter Tirelessly Promoted

A mercurial physicist-poet polymath, Bern Porter moved to Sausalito in 1947 and quickly integrated himself into the local arts community. Arriving from Berkeley as an established publisher of literary works by Henry Miller, Kenneth Patchen, and Robert Duncan, Porter initially stayed with W. Edwin Ver Becke in Sausalito’s Old Town. A fellow poet, Ver Becke was also an artist and playwright who ran an art gallery and established a theater company from his waterfront home. Despite their contrasting artistic sensibilities (Ver Becke tended toward the conventional and representational, whereas Porter embraced modernism and the experimental), Ver Becke was a seminal inspiration for Porter in expanding the scope of his cultural enterprises. Porter would run his own galleries and commit himself to supporting the visual arts while living in Sausalito, a place he grew to advocate for as “one of the greatest cultural centers in the country.”8

Porter’s first art exhibition project was likely the Seashore Gallery of Modern Art, which held two open-air shows in the back gardens of Ver Becke’s Little Gallery By the Sea. As short-lived and informal as was the Seashore, the evidence of Porter’s involvement comes from its selection of artists. In late 1947, the first Seashore exhibition included works by Henry Miller and Porter, together with artists of special local renown, Jean Varda, Enid Foster, and Keith Monroe. By the following spring, the gallery’s program shifted toward the Sausalito moderns and the work of CSFA artists Hultberg, Kuhlman, Lobdell, Stillman, and Jeremy Anderson.

Following the Seashore Gallery, Porter continued to show the Sausalito moderns by turning the living room of his new home in Old Town into an exhibition space. Porter named the gallery Schillerhaus after a sign over the front entrance left by the original homeowner, the early Sausalito settler and woodcarver Charles Schiller.9 Porter exhibited most of the Drawings artists in group shows at Schillerhaus during 1948 and also staged a solo show of seven works by Diebenkorn that summer. By the following summer, Porter had become the new director of the Contemporary Gallery. He made the Contemporary into its own art colony, showing the Sausalito moderns while also featuring lectures by critic Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, readings by poets such as James Broughton, and screenings of filmmakers like Frank Stauffacher.

After an exhibition of paintings by the Sausalito moderns organized by Porter following the release of Drawings, a local columnist declared themselves “utterly irreconciled to the fingerpainting efforts of the modern school of art.”10 With little support from the general public, the Contemporary Gallery was ultimately unsustainable, and Porter left Sausalito in 1950. Upon an apparent self-imposed exile, Porter mysteriously announced the federal government had recalled him for work as a physicist, a claim that Lobdell wrote to Diebenkorn as being “open, wide open, to doubt.”11

4. Phyllis and Richard Diebenkorn Helped Open the Sausalito Nursery School

A place where finger painting is part of the curriculum, the Sausalito Nursery School is an unexpected legacy of the Diebenkorn family’s time in Sausalito. As it was a cooperative nursery, parents were required to contribute, and both Richard and Phyllis were active in the organization. Phyllis regularly served as a point of contact, participated on the decoration committee for an open house, and acted as equipment chairperson when the nursery sought used toys for the children.12 While Phyllis helped keep the school running, its ongoing operation was in doubt. Like the Diebenkorn family prior to Sausalito, the nursery school had no permanent home. Originally sponsored by the Works Projects Administration (WPA) in 1939, the cooperative moved from place to place as accommodations were available. Not having their own home meant that 1947 was spent relocating between South School in Old Town, Central School in New Town, and the Service Men’s Club in Fort Baker. This group of resourceful parents were finally moved to act during the summer of 1948, and the school purchased land in South Sausalito and two wartime warehouses located at an army base in Santa Rosa. A weekend work crew was formed to prepare the two war assets buildings for transport, and Richard Diebenkorn spent part of his summer dismantling the structures that would house the Sausalito Nursery School.13

When the Sausalito Nursery School purchased its lot on the same hillside block above Old Town as Schillerhaus, Bern Porter was agitating the City Council for the recently vacated yacht club to be repurposed into a permanent cultural center.14 Although Porter’s campaign was ultimately unsuccessful, the efforts of at least one of the Sausalito moderns, Richard Diebenkorn, and his wife led to a lasting center for creative growth. The Sausalito Nursery School opened the doors of its new buildings in the summer of 1949, and today, seventy-one years later, the school still welcomes young learners. Conceived as “a school to last forever,”15 the Sausalito Nursery School is hailed as the oldest cooperative nursery in the country.

5. Clyfford Still Went on the Record

Clyfford Still may have only visited Sausalito once, yet it is now understood the artist played an important role in the history of the Sausalito modern art colony. Regarded as the most influential force on the CSFA faculty during this time, Still paid a weekend visit to Sausalito during the summer of 1949 and was subsequently quoted in the local newspaper: “This town’s the only art center for miles around.”16

Considering how critical Still could be of the art world, his praise for Sausalito was likely more of a slight at San Francisco. As noted by the Sausalito News, Still had recently been the subject of contentious coverage in the San Francisco Chronicle.17 At issue were remarks Alfred Frankenstein made in reviewing a show at the Metart Gallery, a cooperative run by artists from Still’s classes at the CSFA. In commenting about Still’s influence on the exhibiting artist, the critic reduced formal comparisons into the notion of a “Still school.” Impassioned responses repudiating this assertion (including one from Mark Rothko) went to press the same weekend that Still escaped San Francisco for Sausalito.

Before his own departure from the Bay Area in the summer of 1950, Still had a valedictory exhibition of his paintings that also was the final show at the Metart Gallery. Among those who volunteered to cover the cost of staging the show and serve as gallery attendants were George Abend, Walter Kuhlman, Frank Lobdell, and Katharine Parker, as well as two other Sausalitans, Jon Schueler and Norman Woodbury.18 Still was selective about how his art was shown and had his work meticulously documented. The archives of the Clyfford Still Museum preserve an announcement card for the Metart exhibition.19 On the back of the card, partly obscured by what appears to be dried glue, is the same roster of artists and artisans presented by Katharine Parker at the inaugural exhibition of the Contemporary Gallery in Sausalito in 1949. Although the back does not identify the presenting gallery or organizer, it may well be a reuse by Metart of an exhibition announcement for Parker’s Sausalito show.20

6. The Sausalito Six

In 1996, Susan Landauer’s The San Francisco School of Abstract Expressionism expanded the historical view of the CSFA at midcentury. Prior to her foundational study, the Sausalito modernist art colony had been largely overlooked or considered only in the context of a few artists.21 Landauer advanced the idea of a definable Sausalito group that included all of the CSFA colleagues who collaborated on the Drawings portfolio—Diebenkorn, Dixon, Hultberg, Kuhlman, Lobdell, and Stillman—and, regardless of where they lived, identified them as the Sausalito Six.22

Following Landauer’s scholarship, the Sausalito Six have often been referenced as if the artists were known that way historically. These artists, however, never organized as a self-identified group as did San Francisco’s Six Gallery (legendary for Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” readings). Neither were they labeled as such by contemporary critics, unlike Abstract Expressionism and the Bay Area’s Society of Six painters. Sausalito was a welcome relief valve for the artists who came together there, with the close proximity of the artists’ studios and the presence of a supportive gallery all within a comfortable distance from the stimulating environment of the CSFA. Instead of projecting a collective identity or even fighting against critics (as in the furor over the “Still school”), the Sausalito moderns were doubtlessly more focused on developing what Lobdell called an “art form that has some substance and guts.”23

Reexamination of archival materials aids in a more inclusive understanding of the art historical narrative as well as expands the previously established canon of recognized artists. Seemingly ordinary items—from newspaper columns to handwritten letters between spouses and friends to early gallery ephemera—provide firsthand accounts of small town happenings in a community of artists, largely lost to time, and highlight the evolving stories of art and place. By contextually interpreting materials surrounding the Sausalito moderns, the names of artists and curators whose contributions were not part of our shared understanding have now been recorded. Contextualization also serves to enliven the biographies of the artists and other community members, highlighting personal elements of their lives. Archival materials surrounding the life and art of Richard Diebenkorn in Sausalito not only provide a broader understanding of the man behind the paintbrush but also allow for new discoveries and connections within the Sausalito modernist art colony.

Carl Schmitz is an independent art historian currently based in Los Angeles.

1. Douglas MacAgy, Director, California School of Fine Arts, letter to the Albert M. Bender Grants-in-Aid Committee, San Francisco Art Association, July 20, 1946, Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives.

2. Sausalito News, February 2, 1950, 4.

3. Wood Lockhart, “The Sausalito Six,” MarinScope, November 4, 2009, A4.

4. While many Drawings portfolios contain sixteen lithographs, an apparently limited amount include seventeen: four by Hultberg, three each by Diebenkorn, Lobdell, and Stillman, and two each by Dixon and Kuhlman. The ones consisting of sixteen have only three lithographs by Hultberg. As examples, the portfolio at the British Museum contains seventeen lithographs, the one at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco has sixteen (three by Hultberg), and the one at the National Gallery of Australia holds fifteen (three by Hultberg and one by Kuhlman).

5. Although another designation,“Sausalito Six,” has been applied in recent years to the informal group of Diebenkorn, Dixon, Hultberg, Kuhlman, Lobdell, and Stillman and addressed later in this text, “Sausalito moderns” is used here in reference to these artists as well as like-minded colleagues. Like other midcentury progressive or avant-garde artists in other parts of the country, they were often referred to by their local newspapers as “moderns,” “modernists,” or as members of a “modern school.” These terms distinguished painters whose work was abstract or non-objective from representational painting, and an artist could be labeled as a modern by both those who derided and those who championed their innovations.

6. Richard Diebenkorn, letter to Phyllis Diebenkorn, December 13, 1948, Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives.

7. “New Sausalito Art Gallery To Open Next Sunday,” Daily Independent-Journal (San Rafael, Calif.), April 18, 1949, 2.

8. “It Happens On Fifth Avenue,” Daily Independent-Journal, Marin Magazine, July 23, 1949, M11.

9. In Schiller’s time, his house at the corner of Main and West streets was often described as being located in South Sausalito. In later years, Porter associated Schillerhaus with Hurricane Gulch. The owner of the house after Schiller, Anna Duffy (known as the “Little Mother of Old Town”), also advocated for Shelter Cove as a replacement for the Hurricane Gulch moniker. Despite the property being just outside of the initial survey map of Sausalito, all of these neighborhood names can generally be considered synonymous with Old Town.

10. “Richard Hackett Exhibits Oils Of Mother Lode, North Coast,” Sausalito News, February 10, 1949, 1. This exhibition review of landscape and still life paintings on display at the Alta Mira hotel opens with an oblique commentary on an exhibition of the Sausalito moderns (Diebenkorn excluded) that closed at the venue a few days prior.

11. Frank Lobdell, letter to Richard Diebenkorn, August [4?], 1950, Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives.

12. “Nursery School Plans for Their Own Building,” Sausalito News, June 10, 1948, 2; “Nursery Mothers to Hostess Tea,” Sausalito News, January 13, 1949, 2; “Crafts Demonstrated at Nursery Meeting,” Sausalito News, February 10, 1949, 2.

13. “Nursery School Buys Property for Structure,” Sausalito News, August 5, 1948, 1; “August 28 Is Date Set for Nursery Bingo Party,” Sausalito News, August 19, 1948, 2.

14. “Price of Yacht Club Too High for City Bid,” Sausalito News, August 5, 1948, 1; “Artists Group Asks City Purchase Of Yacht Club For New Cultural Center,” Sausalito News, August 12, 1948, 3; “Artists Push Plan for City Cooperation,” Sausalito News, August 26, 1948, 1.

15. Jackie Kudler, “SNS—A School to Last Forever,” MarinScope, April 12–18, 1994, 3.

16. “Contemporary Art News,” Sausalito News, August 11, 1949, 3.

17. Alfred Frankenstein, “The Local Galleries,” San Francisco Chronicle, This World, July 24, 1949, 20; Alfred Frankenstein, “Backtalk to a Critic, And a Critic’s Comments,” San Francisco Chronicle, This World, August 7, 1949, 23.

18. The gallery attendants were both past and present students at the CSFA who contributed funds to rent the gallery space as well as their time monitoring the gallery. “Typed manuscript documenting student support of the exhibition ‘Paintings by Clyfford Still,’ Metart Gallery, San Francisco, June 17-July 14, 1950,” CPSA.SB007.B002.F013.002, Clyfford Still Archives, Denver, CO (accessed September 10, 2020).

19. “Announcement for the exhibition ‘Paintings by Clyfford Still,’ Metart Gallery, San Francisco, June 17-July 14, 1950,” CPSA.SB007.B002.F014.002, Clyfford Still Archives, Denver, CO (accessed September 10, 2020).

20. The Contemporary Gallery and Metart Gallery both opened in April 1949 and pursued contrasting exhibition programs. Whereas Metart staged solo exhibitions beginning with the paintings of Ernest Briggs, the opening exhibition at the Contemporary Gallery included work by eight artists in one medium alone. A list of Contemporary Gallery exhibitors that corresponds with the details on the reverse of the Metart announcement can be found in the Daily Independent-Journal, April 18, 1949.

21. Landauer’s timely work challenged the prevailing assumption that the Sausalito group of Abstract Expressionists consisted solely of Diebenkorn, Hultberg, and Lobdell. Earlier art historians were less successful at assessing Dixon, Kuhlman, and Stillman because the artist’s works were less accessible. Dixon apparently had only one major solo exhibition in his lifetime in 1939, Kuhlman was evidently without gallery representation during the majority of the 1960s and ’70s, and Stillman is said to have focused on other concerns beside painting during the ’50s.

22. Susan Landauer, The San Francisco School of Abstract Expressionism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 102.

23. [Judy Stone], “New Art Explained By Sausalitans,” Daily Independent-Journal, Marin Magazine, January 22, 1949, M8.