France, 1978

By Daisy Murray Holman

February 3, 2020

Santa Monica, California

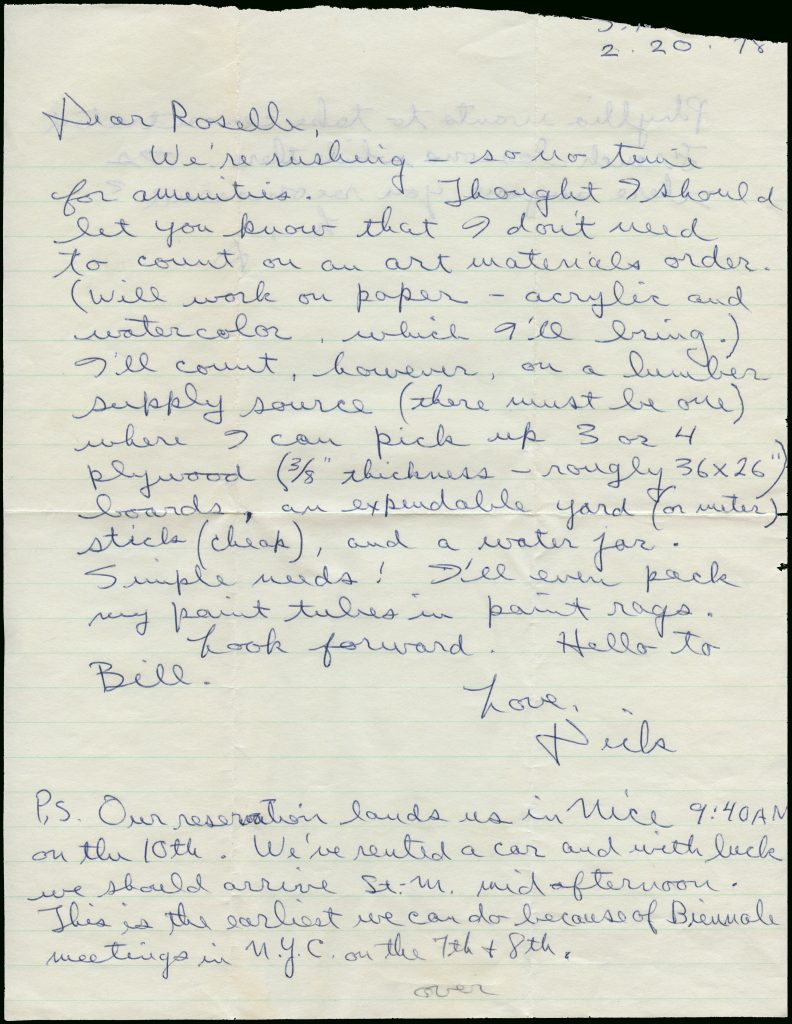

2.20.78

Dear Roselle,

We’re rushing – so no time for amenities. Thought I should let you know that I don’t need to count on an art materials order. (Will work on paper – acrylic and watercolor, which I’ll bring). I’ll count, however, on a lumber supply source (there must be one) where I can pick up 3 or 4 plywood (⅜” thickness – roughly 36 x 26”) boards, and expandable yard (or meter) stick (cheap), and a water jar. Simple needs! I’ll even pack my paint tubes in paint rags.

Look forward. Hello to Bill.

Love,

Dick

P.S. Our reservation lands us in Nice 9:40 AM on the 10th. We’ve rented a car and with luck we should arrive St.- M mid afternoon. This is the earliest we can do because of Biennale meetings in N.Y.C. on the 7th + 8th.

over

Phyllis wants to take concentrated French lessons while there. Is there anyone you recommend? L – D.

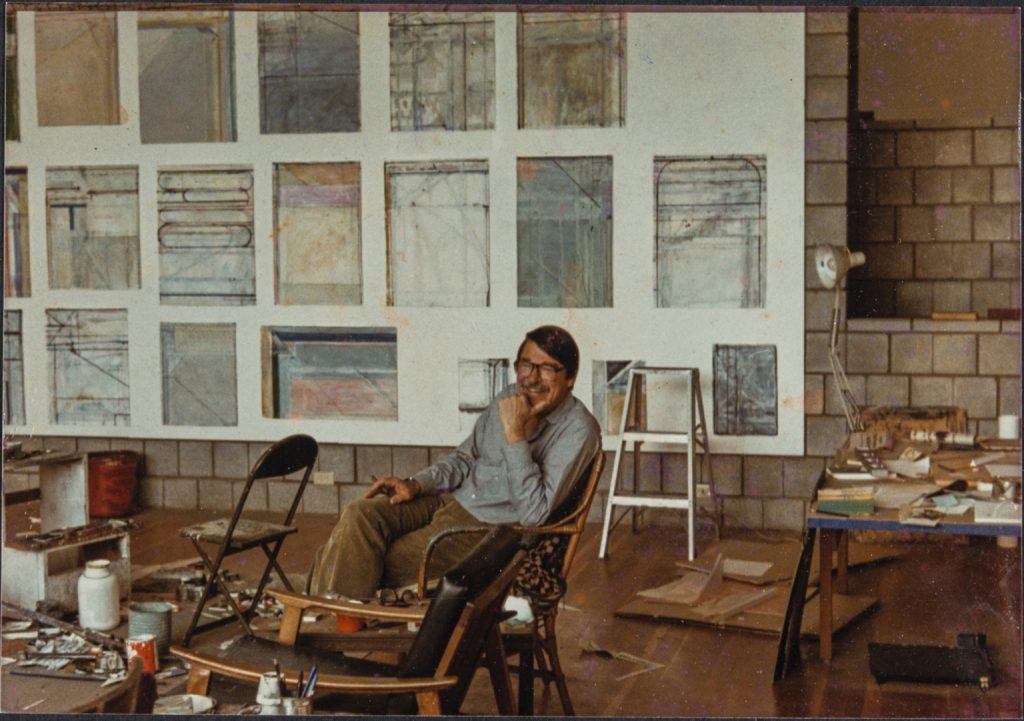

In 1978 Richard and Phyllis Diebenkorn traveled to Régusse, near Aups in Provence, where they settled for four months with their friends William (Bill) and Roselle Davenport. The Davenport’s home, known as Bastide St. Martin, was situated just outside of town and, while not their first visit, it was to be their longest stay. Roselle was also an artist, and Diebenkorn planned to set up shop in her studio.1 His time there was thought to be restful but ultimately unproductive: the artist described bringing back a number of works but ultimately destroying all except one. “The light,” he said, “was too French.”2 In this installment of From the Basement, we examine a rare moment in Diebenkorn’s career when he created a body of work away from home. And, with the help of recently discovered archival material, we arrive at some new conclusions about his artistic production abroad.

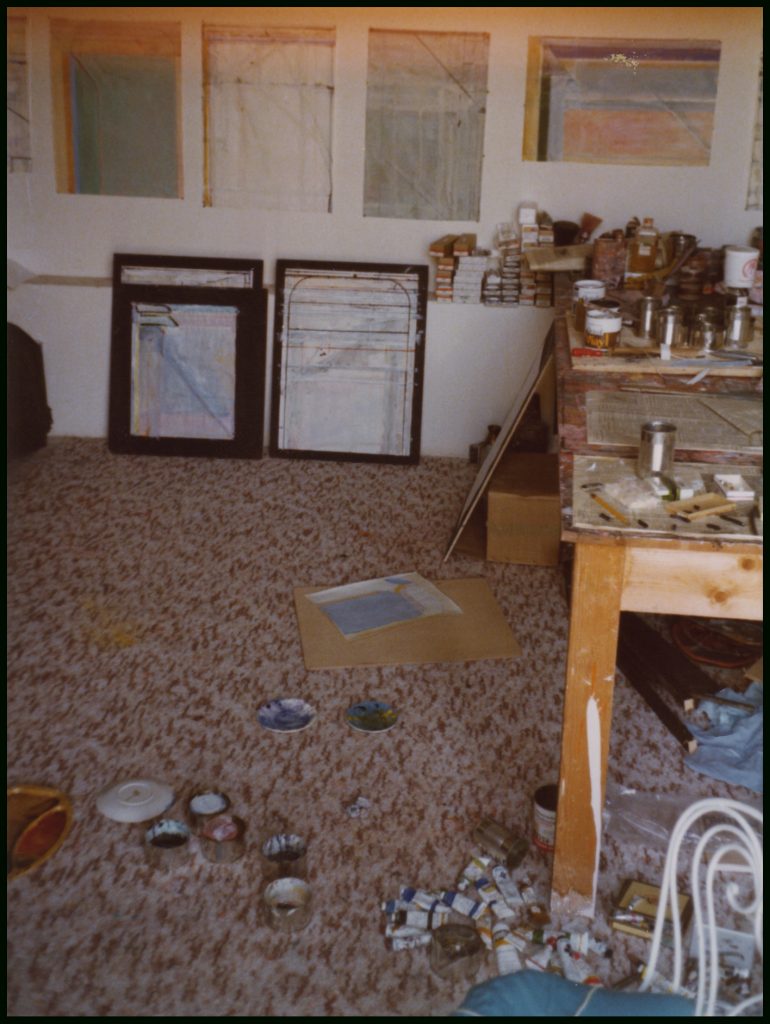

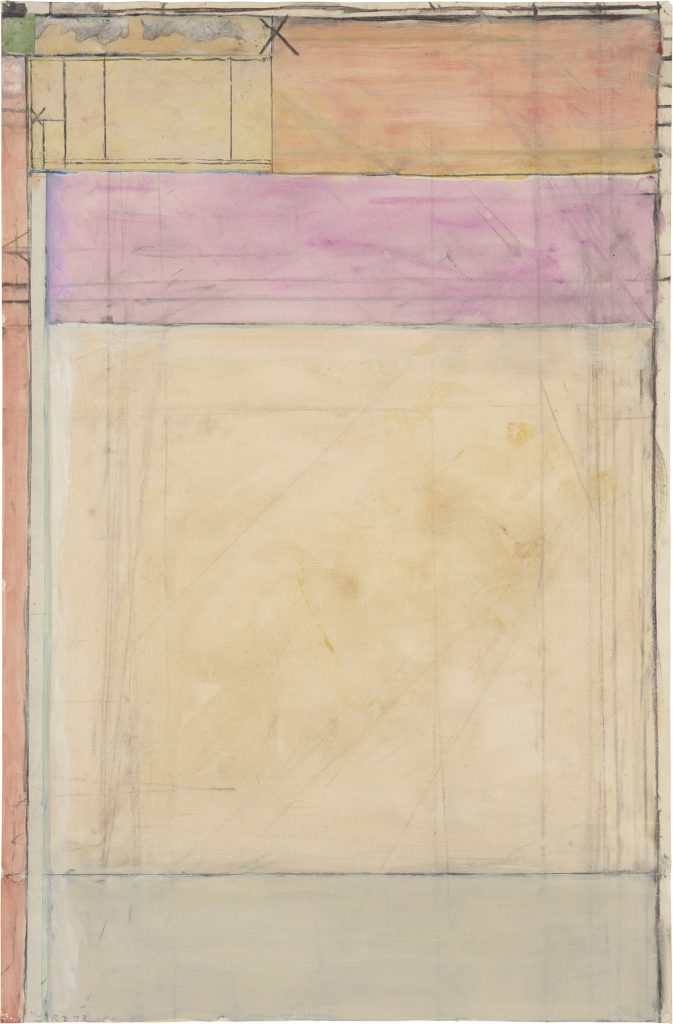

A few months ago, Kay Davenport, daughter-in-law of Bill and Roselle, shared with us a file of correspondence between the Diebenkorns and the Davenports. Among these papers was the letter transcribed above and three photographs of the studio walls taken during Diebenkorn’s 1978 stay. Prior to this we only knew of one photo of the studio in France, but with these new materials we were able to take a closer look. Now we have identified seven works (see example here) in the photos that are still in existence. Most are works on paper in the Ocean Park style that can also be seen in later pictures taken of Diebenkorn’s studio wall in Santa Monica. They appear to be some of the only works from the series produced, at least in part, outside of California.

Long before Richard Diebenkorn traveled to France, he was introduced to its artists in his own backyard. The paintings of Paul Cézanne and Henri Matisse entered his vision as early as high school, and his love of their paintings would eventually stretch to a love of their place. In 1945, while stationed in Honolulu, Diebenkorn met fellow Marine Bill Davenport while wandering around the public library. The friendship would last for the rest of their lives, but when it began neither of them knew that it would also be the catalyst for Diebenkorn’s immersion in Cézanne’s physical world.

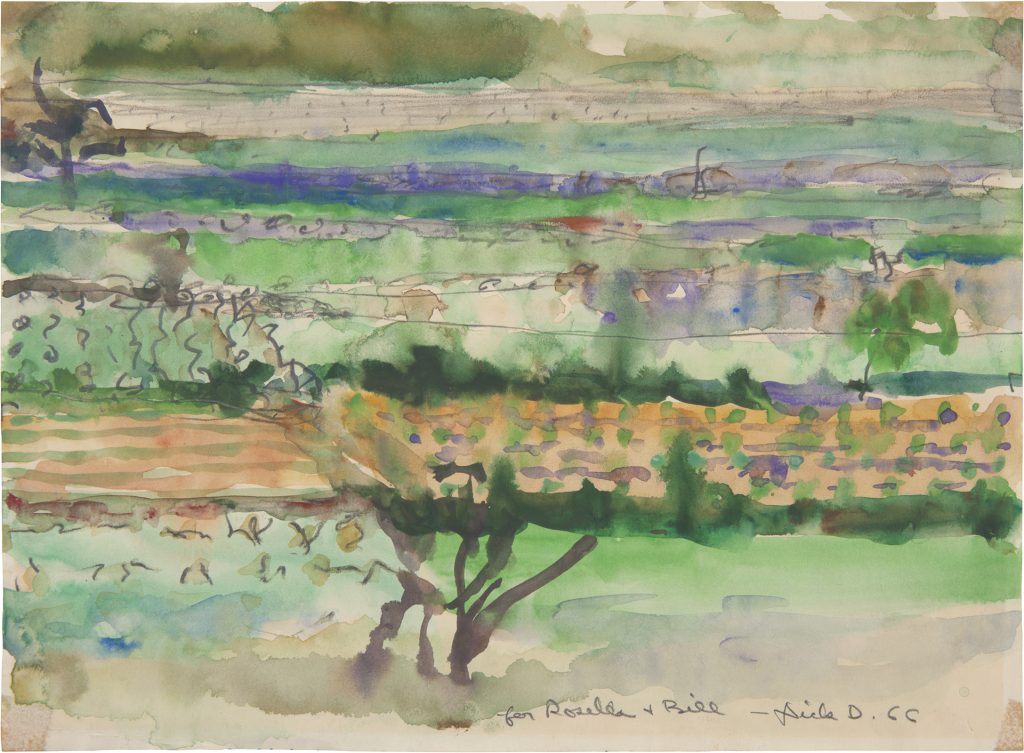

Bill and Roselle Davenport stayed on in Hawaii at the end of WWII. When Roselle was diagnosed with cancer and told she had only a few years to live, they decided that her final years should be in France. (Upon settling there she lived 50 more years.) Bill taught at an American school in Paris, and eventually they bought a second home in Southern France. Phyllis described the house to her grandson: “It was originally a vacation place, I think a 16th or 17th century farmhouse. It had walls [made of] yardstick or something like that and was an absolutely enchanting place.” It was a home they generously shared with the Diebenkorn family time and time again. Diebenkorn did not give his work freely and only rarely gifted drawings to friends or colleagues, but in gratitude Diebenkorn gave the Davenports a few drawings he made in Régusse during his stay (see example here).

Diebenkorn and Phyllis had first visited France while on their way to the Soviet Union in 1964, spending two weeks in Paris awaiting their visas. After this trip—and now with both of their children in college—the two began traveling to Europe during the summers.3 Diebenkorn, the deep looker, went abroad to see; he did not travel to develop a new practice. Apart from occasional glimpses of his trips in his sketchbooks and numerous photo slides, there are few extant drawings that were completed outside of his studios.

In 1978 Diebenkorn was in the thick of making his large Ocean Park paintings. He had recently changed galleries and was preparing for the 1978 Venice Biennale where he was one of the American representatives. In fact, he met with the Biennale organizers in New York right before his departure to France. While we cannot know what Diebenkorn was looking for, we do know that going four months without studio time was unusual for the artist and went against his desire for regular solitary hours in his own space.

These seven works on paper showcase Diebenkorn’s consistency as an artist. His acute sense of what and how he saw, and how he expected that vision to appear in his work, are apparent when the Ocean Park works on paper are studied as a whole. These works are not outliers; they carry a number of his Ocean Park tropes: an arch, lines painted over in gouache, stripes of color along the upper edge, washy areas of pastel and primary colors varying in density, and the “scaffolding” nature of the lines across the paper.4 Cezanne’s light does not shine through their seams. Instead the works fit seamlessly into his tremendous body of work suffused with a light that is entirely Diebenkorn’s own.

The majority of the recognizable France works can also be seen in various 1979 photographs from his Santa Monica studio. While most of them appear unchanged (which is hard to confirm due to the quality of the photos), there is one work in particular that says something of Diebenkorn’s practice. The drawing reproduced on the cover of the 2019 monograph, Richard Diebenkorn: A Retrospective, was worked on first in Roselle’s studio in 1978. It took hours of staring at the newly found photographs from France to discover that the work is one and the same. Diebenkorn would later remove a blue triangle (visible in the photo) and replace it with a yellow square, a small change with dramatic results. Was it the blue that was “too French”? Why did Diebenkorn decide to save this work but not others? With these new photos, we can ask deeper questions about Diebenkorn’s process and compare what he perceived as his failures to his successes.

The photographs and accompanying letter are a testament to the endless pursuit of collection and research, and the critical component of friendship. The Diebenkorn–Davenport relationship lived beyond the lifetime of the key players. Their mutual fondness, respect, and trust passed on to their children now is a great boon to scholarship.The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation is endlessly grateful to Kay Davenport for sharing her family’s materials with us. The story can always change.

1. His makeshift studio at the Davenport home was one of only a few known temporary studios he had while traveling. See also From the Basement post, “Meeting Santa Cruz Island.”

2. Gerald Nordland, comment in a draft of Nordland’s Richard Diebenkorn (New York: Rizzoli International, 1987; rev. ed. 2001), Richard Diebenkorn Foundation Archives.

3. Much has been written about these trips and Diebenkorn’s museum visits abroad—collections from the Louvre to the Uffizi to the Prado—and of his breathtaking visits to view Pompeii and Etruscan ruins. See Jane Livingston, The Art of Richard Diebenkorn, exh. cat. (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1997), 28.

4. John Elderfield presents the idea of a scaffold as a characteristic of the Ocean Park works throughout his 1988 essay on Diebenkorn’s drawings. John Elderfield, The Drawings of Richard Diebenkorn, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art; Houston: Houston Fine Arts Press, 1988).