1946

17 January–11 May: Enrolls at the California School of Fine Arts (CSFA) in San Francisco on the GI Bill. The school, managed by the San Francisco Art Association (SFAA), is in a period of transition due to the presence of a new director, Douglas MacAgy, and the expected influx of money and students using the GI Bill benefits. MacAgy— educated in the arts, and assistant to Grace McCann Morley, the director of the SFMA, before being hired at CSFA36—is devoted to modernizing the school, and hopes to use the surge of funding and student enthusiasm to infuse the school with a newfound energy after years of decline.37 He brings in a progressive faculty to work with the new group of mature and eager artists returning home from the war. Elmer Bischoff is hired to join David Park, Hassel Smith, and Clay Spohn as instructors in the painting department. These four men will have a significant impact on Diebenkorn’s life and career.38 Diebenkorn is one of the first veterans to enroll at the school.

Takes courses in sculpture with Zygmund Sazevich, life sketch with James McCray and Elmer Bischoff, and lithography with Raymond Bertrand. He takes three classes with David Park: Painting III, where he is recommended to the honor roll; Artist Materials; and Line Drawing, which he transfers to after withdrawing from Clay Spohn’s life drawing class, after two weeks.39 Park will become one of his most important teachers and friends.40 Diebenkorn learns to teach by watching Park in the classroom, in particular noting his use of poetry for quick drawing exercises.

He would say, “Take this subject. You have two or three minutes,” . . . or in the extreme, five minutes. He got you really excited about catching the essence of an object or a poem. For example, I’ll never forget Wallace Stevens’s “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird.” He read it to us, and the class drew an exercise for each stanza. He had an endless repertoire of subjects, and each one had something marvelous that sparked you.41

Park invites Diebenkorn to his studio in Berkeley.

That invitation was just great for me. It meant we were friends. And if you as a painter want somebody to take a look at your work, then it means that they have respect for you as a painter and respect for your eye. It all happened in the first semester.42

17 April–5 May: Shows North Coast (cat. 492) and War Forms (cat. 496) at the SFMA’s Tenth Annual Watercolor Exhibition of the San Francisco Art Association. Erle Loran is a juror for the exhibition; the show travels to the Henry Art Gallery at the University of Washington in Seattle.43 These early abstractions range from the recognizable landscape to Cubist-inspired planar paintings to sketches of small squares holding folded forms and figures; Diebenkorn’s palette focuses on primary colors.

24 June–2 August: Takes two classes at CSFA, painting and line drawing, both with Park. Works appear in two group exhibitions at the Pat Wall Gallery in Monterey, Calif., alongside work by Edward Corbett, Robert McChesney, and Jean Varda.44

With Park, sees Robert Motherwell’s paintings in Fourteen Americans, one of the exhibitions from the important series selected by MoMA’s curator, Dorothy Miller, at the SFMA.45 The museum’s holdings at the time include Pollock’s Guardians of the Secret (1943; see Nordland essay, fig. 15), Gorky’s Enigmatic Combat (1936–37; see Nordland essay, fig. 32), and Mark Rothko’s Slow Swirl at the Edge of the Sea (1944; see Fine essay, fig. 111).

October: Dry Reef and Land Forms (cat. 497) and Shrine (cat. 509) are selected for the Sixty-Sixth Annual Exhibition of the San Francisco Art Association: Oil, Tempera, and Sculpture. Douglas MacAgy and David Park are jurors.

Wins Albert Bender grant-in-aid for $1,200; while the Bender Memorial Trust is a separate institution, the SFAA supports the selection process. MacAgy encourages Diebenkorn to apply for the prestigious grant, stating in his letter to the grant committee that he knows of “no one who would profit more” from the support. Daniel Mendelowitz writes in his recommendation, “Mr. Diebenkorn is a student with very unusual abilities and has the intensity of interest and concentration of purpose that makes a real artist.”46

Decides to use the grant to live and work in New York City. MacAgy promises Diebenkorn a job as an instructor at CSFA upon his return.

Diebenkorn writes in his application,

My plan is to experiment with form and the methods of presenting it and to develop my understanding of what I want to paint. I want to live in New York for a year in order to see and study the art of all periods. I hope to discover by this study my relationship to art, that is, how my expression of what I find about me is similar to and different from established art works.47

Travels to the East Coast ahead of Phyllis and Gretchen. Visits the Samuel Kootz Gallery at 15 East Fifty-Seventh Street in New York because of his interest in Robert Motherwell and William Baziotes, both of whom showed with Kootz. Meets Baziotes at the gallery.

[It] was quite a few years before the AE “landslide.” . . . One of the first things I did when I visited New York in 1946 was to go to the Samuel Kootz Gallery and ask to see some of Baziotes’ work. I suppose I expected Baziotes’ work to be just hanging there. I was very young at the time (24) and I didn’t know the ropes.

But Sam Kootz said, “Well, Baziotes just happens to be here, in my office.” So he took me back, and then they hauled out a bunch of pictures from storage. They were very good to me, and then Bill Baziotes had me to his house for dinner. I took a little package with me and showed him some of the things I was working on.

So that was my first contact with Abstract Expressionism in the flesh.48

While in New York, also meets Mark Rothko and printmaker Stanley William Hayter of Atelier 17.

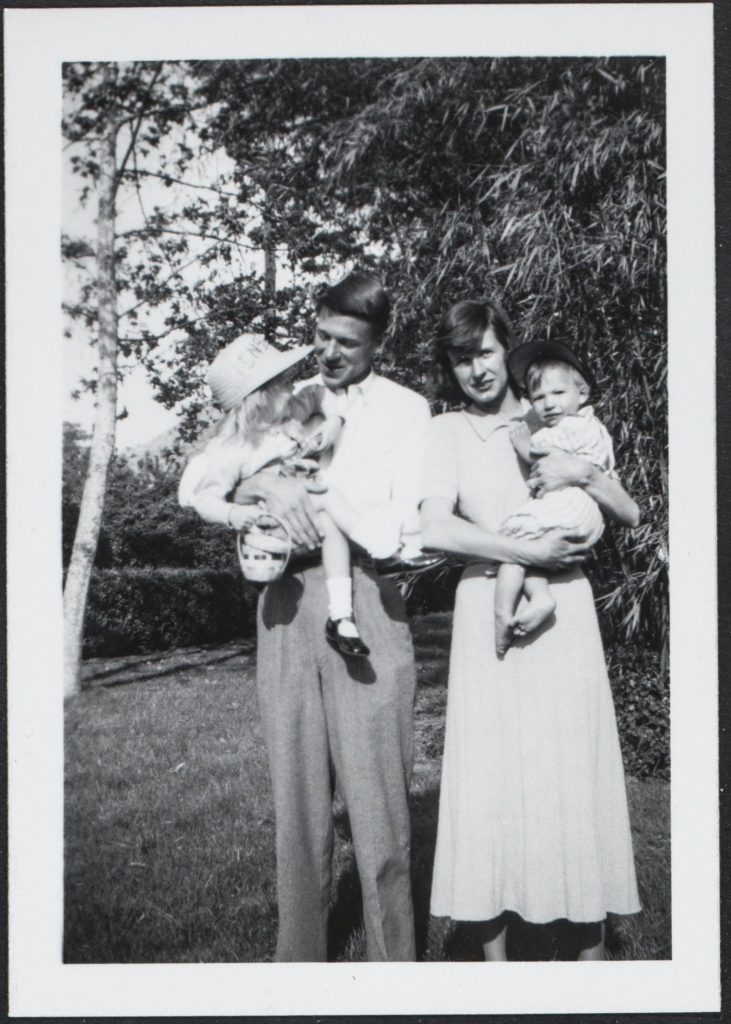

November: Finding New York City crowded and expensive, moves to Woodstock, New York, upon the suggestion of an artist acquaintance.49 Meets the artists Raoul Hague, Melville Price, Bradley Walker Tomlin, and Judson Smith, who makes his art library available to the artist.50 Phyllis and Gretchen live with Diebenkorn in a two-bedroom apartment; he uses one of the rooms as a studio and follows a strict painting practice, working whenever the sun is up. The family spends the Winter snowbound. Phyllis recalls,

I’d never been in snow like that, before or since. Never lived in it. We lasted until [June]. And then we packed up and drove back, across the country. . . .

I think Dick was disappointed. I think he wanted to be in New York. But, more than that, [he wanted] to work all the time. . . . I’m sure he would have preferred to live in New York, and we did try that again a few years later. But, in a way, I think he was happy that he really worked. He painted from dawn till dark.51

24 November: Grandmother Florence Stephens dies.

1947

I have been able to concentrate continually on my work and although oil painting has been my main concern I have painted watercolors, cut collages, drawn, and done bits of sculpture. I’ve solved most of the problems I brought with me from home and now have a new, more imposing set. I’ve certainly moved and I feel a great indebtedness to those enabling me to do so.

I’ve also met New York artists to whom I’ve talked, I’ve seen their work and have watched the New York exhibits. These things plus a fresh environment have made the first third of my Bender year a success.52

Winter–Spring: Travels with Phyllis to New York City occasionally while living in Woodstock.

During Diebenkorn’s time on the East Coast, Sam Kootz installs a large show of Picasso’s recent work; it is Picasso’s first New York show in seven years.

Diebenkorn seeks out works by Miró, whom Park encouraged him to study before leaving for New York. Visits the Museum of Modern Art, and sees Miró’s Person Throwing a Stone at a Bird (1926), Matisse’s Piano Lesson (1916; see Elderfield essay, fig. 71), and Picasso’s Three Musicians (1921; see Nordland essay, fig. 20).53 Also spends time with a book of Miró reproductions.

In Woodstock Diebenkorn produces small Cubist-inspired panels. Phyllis remembers, “He said afterward, ‘I learned about color.’ ” Few works survive from this period. Discussing these works, specifically Advancer (cat. 504), Diebenkorn mentions the stimulus that Park’s “personal variation on Picassoid double portraits—more personal than Gorky’s” provided.54

Summer: Family returns to the Bay Area. Diebenkorn works as an instructor at CSFA, teaching life drawing.55 He remains an instructor at the school until January 1950. CSFA is not yet adegree-granting institution, and Diebenkorn is able to teach without previous experience or a college degree of his own.

During his absence, CSFA has fully embraced Abstract Expressionism, and the number of GI Bill students grew rapidly. “The revolution occurred . . . I don’t know where it came from. The spirit of ‘let it all hang out’—the spirit of great enthusiasm, great excitement and celebration.” 56

Things just got turned over and the place became much more active and Abstract Expressionism caught on and Park was a little bit left out at that point, because these, the GI Bill people were rebellious and set to turn things over, and didn’t paint where they were supposed to paint in the school. . . . They were painting out in the halls and somebody was making tar effigies out behind the school, it was pretty chaotic. . . .

When I came back to the school after working snowbound in Woodstock, I brought work to show. I remember I spoke [to] John Grillo, who I had thought was a very talented guy, and we had sort of worked in the same room and showed our paintings to one another. And we were really quite simpatico. And I felt he thought very highly of my work. And I came back and wanted to show my pictures—they were all small little pictures—to David and Grillo, and some of the people. And so I remember walking into the school, and I had this portfolio with about twenty of these little panels, and then here I look at the school and the pictures are massive size, and so physical and broadly painted. I can remember showing these things to Grillo and I could see, he was being very polite, but he was thinking, “Oh, this is the guy I thought was so good.”57

Clyfford Still, whom MacAgy hired in 1946, quickly gains a following at the school; his July 1947 solo show at the Legion of Honor makes a deep impact on the community and is widely discussed. MacAgy also invites Mark Rothko to be a visiting lecturer that Summer. While Diebenkorn does not attend Rothko’s class, he may have helped the older artist install a show.58

August: The SFAA lists Diebenkorn as an “active artist.”59

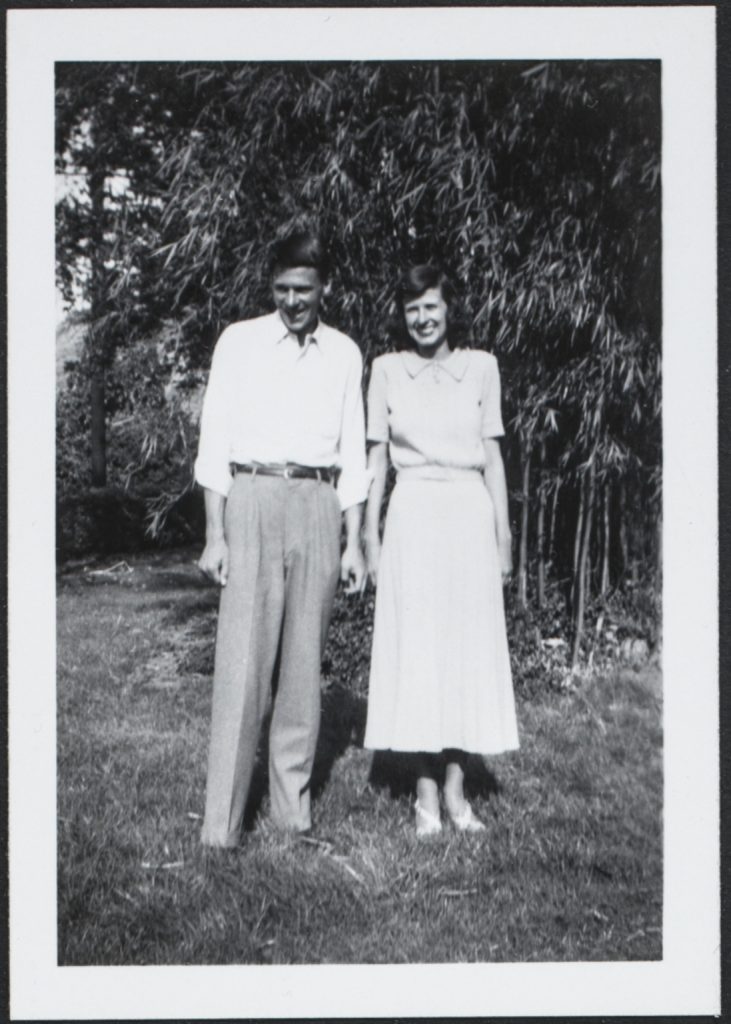

With his father’s help, buys a house with a view of the San Francisco Bay at 40 Bulkley Avenue in Sausalito, where he uses the attic for his studio. The town is a more economical option than San Francisco, located across the Golden Gate Bridge, and has an active artists’ community.

25 August: Son, Christopher, is born.

Fall: Teaches Drawing and Composition; Clyfford Still and Edward Corbett teach the other sections of the same course. Also teaches Life Drawing; peers Frank Lobdell and Walter Kuhlman are students. Reconnects with Park and befriends Elmer Bischoff.

After Woodstock, David and I picked right up. There was no catching up—no need to catch up. We were better friends when we saw one another again. . . . That’s where Elmer came in. They had got to know each other while I was away and the three of us now knew each other.60

Diebenkorn also becomes close with artist Hassel Smith; the two share a great love of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat comic strip series. Park, Bischoff, Smith, and Diebenkorn begin meeting at each other’s studios.

Every Saturday we would go to the studio of a different one of the four, and we’d get pretty drunk by the end of the day, but we got a chance to look over the others’ work of the month. And there was a lot of talk and sharing of ideas and attitudes. We became a lot more intimately acquainted with what we were doing. We did a lot of talking.61

Phyllis remembers,

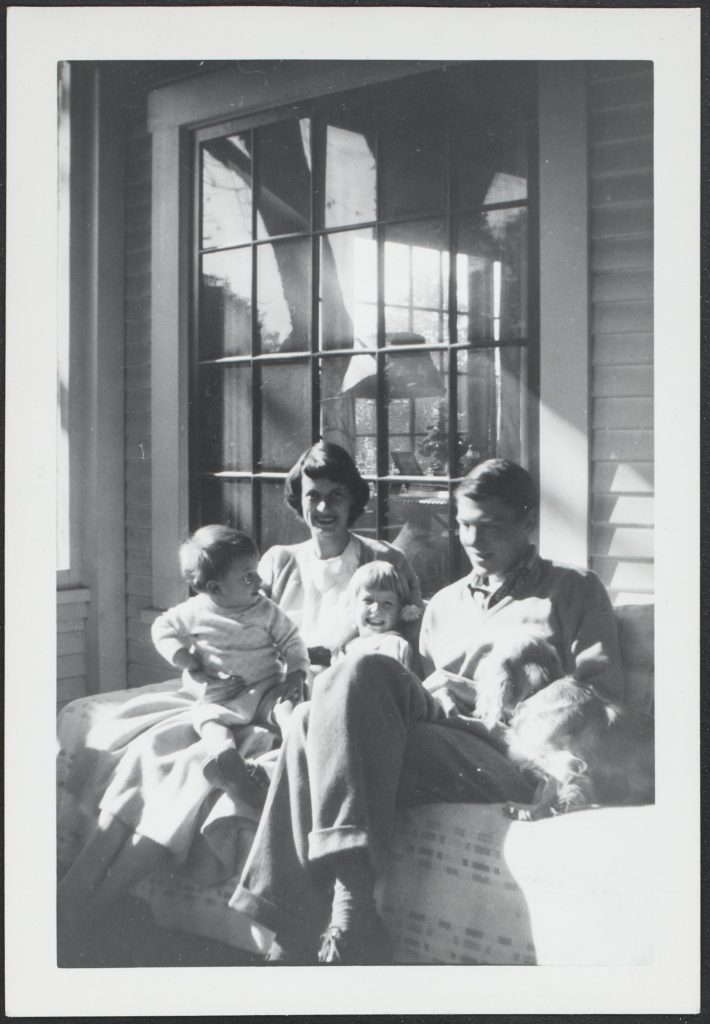

I think they were all very excited. It was after the war, and the students were great. They were all on the GI Bill, and older, and dedicated, and smart, and they weren’t sort of rah-rah college students—they knew what they were there for. And Abstract Expressionism was in and it and they were all doing it. They were excited. Everybody was excited. And they traded paintings back and forth. And they went to each other’s studios and they stayed up late and talked. It was a very exciting time. . . . It was a sort of stodgy school before that, or more academically oriented. And [MacAgy] brought in all this new stuff, and anything went, which was exciting.62

Bischoff recalls,

There were a lot of students there who were very conscious of having . . . lost time out from major pursuits and major concerns of a personal nature, certainly, in the war. . . . A lot of intensity was born from this feeling. The freewheeling quality, I think, came from the attitude that there were not really instructors and students as much as there were older artists and younger artists. . . . There was a great deal of openness between the faculty members too, where we’d go around visiting one another’s studios and commenting on one another’s work. . . . There was much mutual trust, much mutual regard. Nobody was climbing over anybody, nobody was trying to be top dog by climbing over somebody else.63

The school’s social life partly revolves around the Studio 13 Jass Band, named after a studio at CSFA, which plays Dixieland jazz at the school’s raucous parties, where students, instructors, and administrators mingle.64 Diebenkorn briefly picks up the trombone, but does not move beyond the basics.65

Enters first mature period.66

1948

Winter: Begins teaching Figure Composition at CSFA.

February: Wins the Emmanuel Walter Purchase prize at the 67th Annual Exhibition of the San Francisco Art Association: Oil, Tempera, and Sculpture. Bischoff, Clay Spohn, and Robert McChesney sit on the jury.

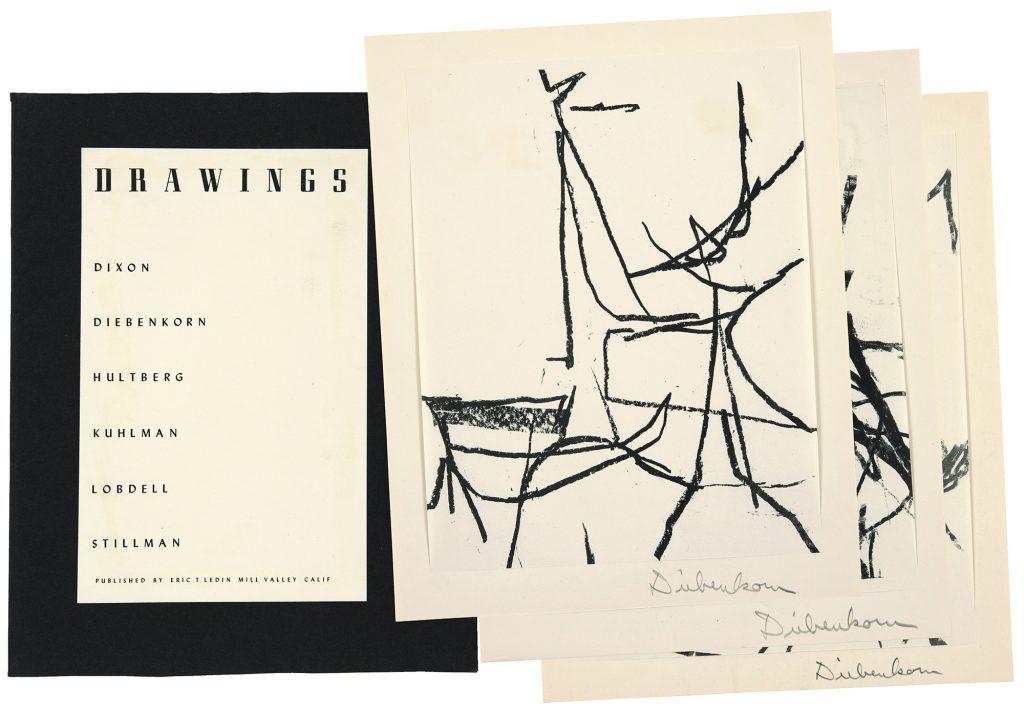

Occasionally draws with a group of other CSFA related artists in Sausalito. Diebenkorn, Lobdell, Hultberg, James Budd Dixon, Walter Kuhlman, and George Stillman are referred to as the “Sausalito Moderns” by poet-physicist Bern Porter.68 Porter periodically organizes shows for the artists at the Schillerhaus and the Contemporary Gallery, both in Sausalito; the events are publicized in the Sausalito News. The artists collaborate on a portfolio of lithographs: Drawings, edited by Lobdell and printed by Eric T. Ledin. It is considered the first group portfolio of Abstract Expressionist prints.69

Spring: Reads Clement Greenberg’s “The Crisis of the Easel Picture” in the Partisan Review, which is printed alongside four works by Willem de Kooning.70 Becomes increasingly aware of contemporary art.71 Later states, “I am decidedly in de Kooning’s debt.” 72 De Kooning’s first one-man show hangs at the Charles Egan Gallery in New York; he is forty-four.73

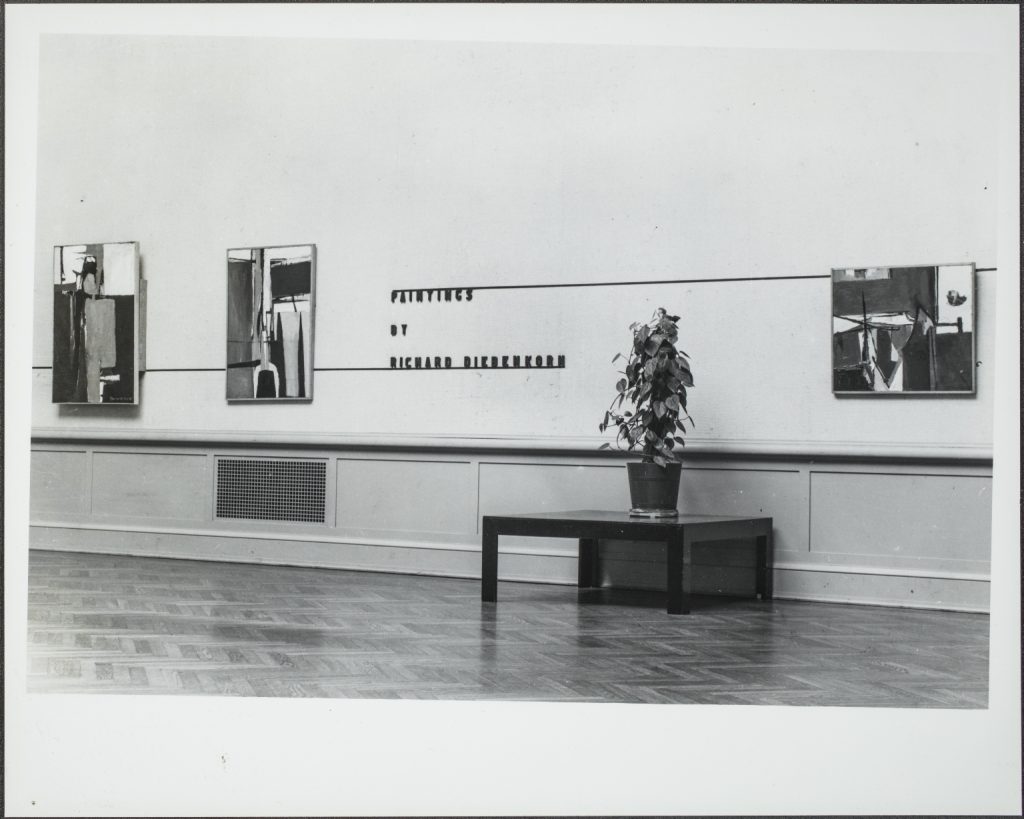

Summer: At the Legion of Honor, the twenty-six-year-old artist’s work hangs in his first one-man show. According to Phyllis, the early recognition, and the potential of perceived precociousness, made Diebenkorn uncomfortable.74 The fourteen oil paintings feature ochers, reds, deep greens, whites, blacks, and the occasional blue; the Stillian sliver and rough texture are apparent, as is Park’s thick handling of paint and challenging colors. During this time Diebenkorn focuses on the formal qualities of his works.75

June: Works appear in the Twelfth Annual Drawing and Print Exhibition of the San Francisco Art Association.

October: Two untitled pieces are selected for the Twelfth Annual Watercolor Exhibition of the San Francisco Art Association (20 Oct.–14 Nov.). As a member of the SFAA, Diebenkorn sits on the jury with other participating artists; this is common practice for the association’s annuals.

Sometime in 1948 Diebenkorn visits Clyfford Still’s studio at CSFA. Afterward Diebenkorn recounts,

Clyfford came up to me in a hallway and said, “I’d like to see what you’re working on.” Phyllis and I were living in Sausalito then—it wasn’t the self-conscious community that it is today— and we invited Clyfford over for lunch. When he arrived, we chatted a bit, and then I took him upstairs to my studio and showed him a number of my paintings. This time, he said nothing. Then we went downstairs again, into the dining or living room . . . and sat there waiting to eat. At this point, Clyfford caught sight of a painting of mine that was leaning against a wall, and he said, “I like that.” Of course, I felt embarrassed by this compliment and thought I had to chop it down. I thanked him, but added that I wasn’t sure the color really worked. Unfortunately, this wasn’t the sort of thing you could say to Clyfford Still. What was this about color working? That sort of talk was for pedants and old-fashioned art teachers. Clyfford didn’t believe in craftsmanship—only in the emotional impact of the entire image. He got up, put on his coat, and, without saying a word, walked out.76

1949

January: Stanford University grants Diebenkorn his bachelor’s degree.77 Diebenkorn is elected chairman of the SFAA Artist’s Council.

24 February–20 March: An untitled work is included in the Sixty-Eighth Annual Exhibition of the San Francisco Art Association: Oil, Tempera, and Sculpture. Edward Corbett is a juror.

3–29 May: Participates in a group exhibition in Detroit, Little Show of Work in Progress: San Francisco Artists. The abstract works of Diebenkorn, Bischoff, and Park are not well received. Reviewer Joy Hakanson writes in the Detroit News, “If this California work is progress, give us a one way ticket to the 15th century. . . . Their canvases look like dirty, lumpy palettes mopped with a rag.”78

Summer: Rothko teaches again at CSFA, but Diebenkorn, sick with the mumps, is unable to spend time with the older artist.

20 June–25 July: Untitled #2 (Sausalito) (cat. 677) appears in New Works by Bay Region Artists at the Los Angeles County Museum.

30 September–13 November: Untitled #22 (cat. 586) is selected to appear in the California Centennials Exhibition of Art at the Los Angeles County Museum; Andrew Ritchie, curator of painting and sculpture at MoMA, sits on the jury. James Byrnes, curator of painting at the Los Angeles County Museum, and Dr. William R. Valentiner, co-director of the museum with James Breasted, take notice of Diebenkorn’s painting and try to find a buyer. Paul Kantor, then running the Fraymart Gallery, also a frame shop, on La Brea Avenue, is taken by the piece and pursues the artist. Arthur Millier reviews the exhibit in the Los Angeles Times and mentions Diebenkorn’s work: “The colorful emotional-abstract painting practiced in the San Francisco area is typified here by Richard Diebenkorn’s Untitled [#22], a yellow-glowing canvas which suggests the sea.”79

December: Helps Clay Spohn create his Museum of Unknown and Little Known Objects for the CSFA New Year’s Artists’ Ball.80

Decides to leave CSFA. His position at the school is no longer rewarding; the long hours spent at the school and commuting compromise his time in the studio, while the low pay constricts his ability to buy materials.

I could kind of see the handwriting on the wall. I was the bottom man on the totem pole of the school . . . Still was at the top. But at any rate, I had all of the GI Bill [money] that I hadn’t touched. I was struggling to make ends meet and to buy paint. My students could go to the school store and come back loaded with these bags of materials. . . . I decided I was going to be on the GI Bill.81

Applies to the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, choosing New Mexico because of a “childhood romance of the Southwest and its history and its look. I went through there on a train once.” 82

36. Douglas MacAgy studied at the University of Pennsylvania, the University of Toronto, the Barnes Foundation, the Courtauld Institute, and the Cleveland School of Fine Arts. Before working at CSFA he was a curator at the Cleveland Museum of Art and was later hired as an assistant to Grace McCann Morley, director of the San Francisco Museum of Art.

37. Douglas MacAgy, “Revising an Arts Training Program,” MKR, 14 Oct. 1946, 3.

38. Susan Landauer, The San Francisco School of Abstract Expressionism (Laguna Beach, Calif.: Laguna Art Museum; Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 35–37. For further information on the period, Landauer’s book provides an in-depth and richly researched history.

39. Richard Diebenkorn, artist file, San Francisco Art Institute Archives.

40. Richard Diebenkorn, interview with Nancy Boas, “Richard Diebenkorn interviews with Nancy Boas, August 11, September 29, and October 24, 1990, Healdsburg, California,” transcript, RDFA, 1.

41. Richard Diebenkorn quoted in Nancy Boas, David Park (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 111.

42. Ibid., 95.

43. The San Francisco Art Association’s annual exhibitions were held at the San Francisco Museum of Art, which was opened by the association in 1935.

44. Susan Landauer, Edward Corbett: A Retrospective (Richmond, Calif.: Richmond Art Center, 1990), 52–53.

45. Motherwell was well represented in the show, with five works shown in San Francisco: Flam, Rogers, and Clifford, Robert Motherwell Paintings and Collages, cat. nos. P19, C7, C17, C19, and C25.

46. Daniel M. Mendelowitz, letter for Albert M. Bender Grants-in-Aid application, 24 July 1946, San Francisco Art Institute Archives.

47. Diebenkorn, statement for Albert M. Bender Grants-in-Aid application, 31 July 1946, San Francisco Art Institute Archives.

48. Diebenkorn with Butterfield, Pentimenti, n.p.

49. “Woodstock News,” Kingston Daily Freeman, 1 Nov. 1946, 7.

50. Nordland, Richard Diebenkorn (2001), 23.

51. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.

52. Richard Diebenkorn to Dr. Monroe E. Deutsch, CSFA vice president and provost, 10 Feb. 1947, San Francisco Art Institute Archives.

53. Tuchman, “Diebenkorn’s Early Years,” 7. In a 1981 letter to Bruce Grenville, Diebenkorn lists seeing Piano Lesson in 1947. Diebenkorn to Grenville, 1951, RDFA. Three Musicians was on view at MoMA in the Spring of 1947.

54. Ibid., 7–8.

55. Summer 1947 class schedule, term runs 23 June– 1 Aug., San Francisco Art Institute Archives. Diebenkorn is not listed by name in the semester course catalogue but his roll book confirms his presence on campus.

56. Diebenkorn, interview with Boas, 12.

57. Diebenkorn, interview with Larsen, 1 May 1985.

58. Ibid. Diebenkorn stated that he met Rothko during his first time in New York and helped Rothko hang a show in San Francisco that Summer in 1947; however, it appears that Rothko did not have a show in the Bay Area in 1947 or 1949, the two Summers he taught at CSFA. Diebenkorn may be talking about a show in New York.

59. “Membership,” San Francisco Art Association Bulletin, Aug. 1947, n.p.

60. Diebenkorn, interview with Boas, 6.

61. Ibid., 19.

62. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.

63. Oral history interview with Elmer Bischoff,

64. 10 Aug. and 1 Sept. 1977, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview conducted by Paul Karlstrom.

65. For more on the CSFA social scene and the development of the Studio 13 Jass Band, see Boas, Park, 100–101; and Bischoff, interview with Karlstrom, 10 Aug. and 1 Sept. 1977.

66. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.

68. At the time, Dixon was living in San Francisco and Stillman in Berkeley.

69. See Lanier Graham, The Spontaneous Gesture: Prints and Books of the Abstract Expressionist Era (Canberra: Australian National Gallery, 1987), 11.

70. Partisan Review, Apr. 1948, unnumbered pages, 481–84.

71. Elderfield, Drawings of Richard Diebenkorn, 199–200.

72. Richard Diebenkorn quoted in Gerald Nordland, Richard Diebenkorn (Washington, D.C.: Washington Gallery of Modern Art, 1964), 11.

73. De Kooning chose to not participate in a oneman show until gallerist Charles Egan convinced him. De Kooning “resisted the blandishments both from dealers and from occasional patrons. It was well known that he and Gorky chose poverty rather than to compromise their work.” Dore Ashton, New York School (Oakland: University of California Press), 166–68.

74. In a 2013 discussion with the author about Diebenkorn’s first solo show, Phyllis commented that Diebenkorn said, “What have I done?”

75. Diebenkorn, interview with Boas, 19.

76. Diebenkorn quoted in Hofstadter, “Almost Free of the Mirror,” 63.

77. Letter from Stanford Academic Council, 7 Jan. 1949, RDFA.

78. Joy Hakanson, “Sarkis-Midener Exhibit at Market,” Detroit News, 1 May 1949.

79. Arthur Millier, “Art Trends Traced at Centennials Show,” Los Angeles Times, 2 Oct. 1949.

80. The ball, known as the Parillia Ball, was an annual event, but the 1949 party was the first occurrence since World War II.

81. Richard Diebenkorn, interview with Mark Lavatelli, 15 Nov. 1978, in Mark Lavatelli, “The Albuquerque Paintings of Richard Diebenkorn” (MFA thesis, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, 1979), 23.

82. Ibid., 24.