1976

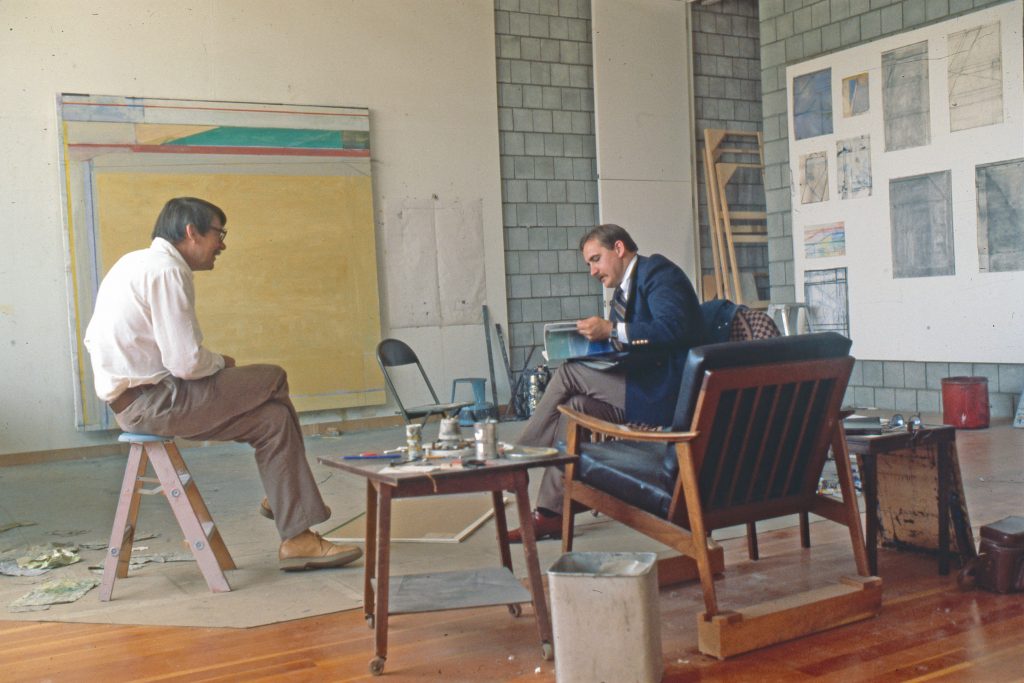

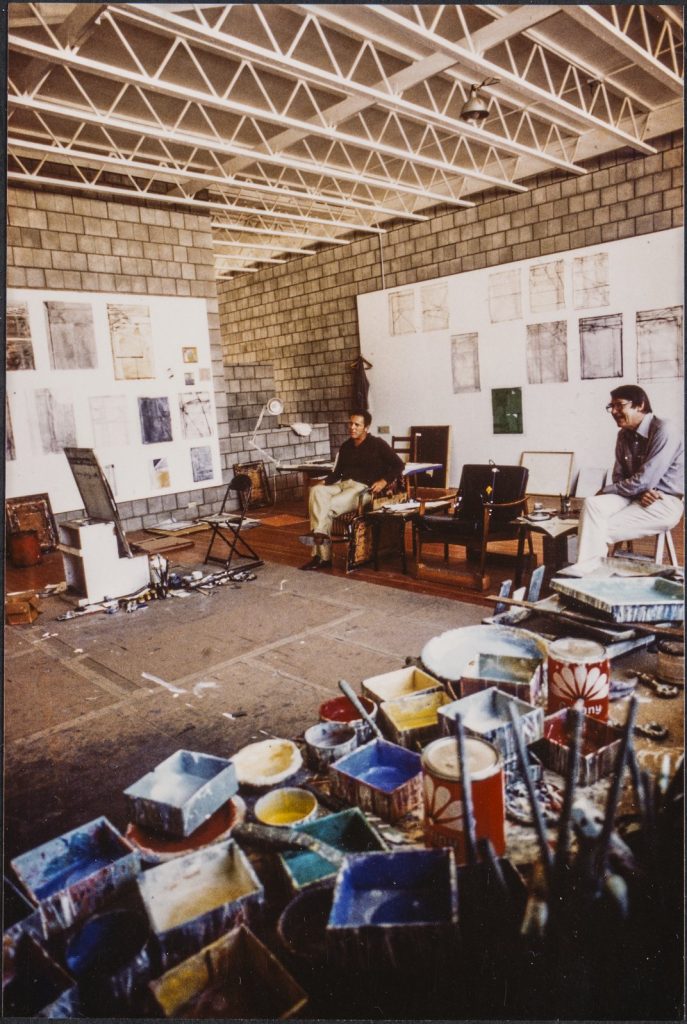

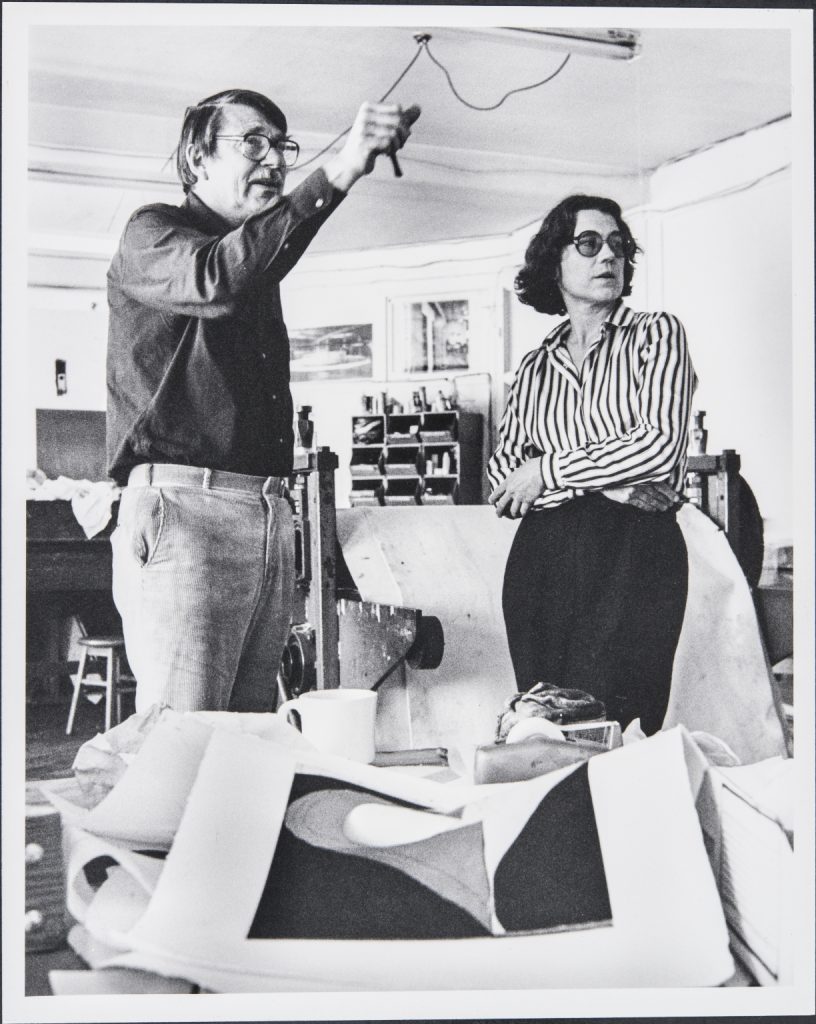

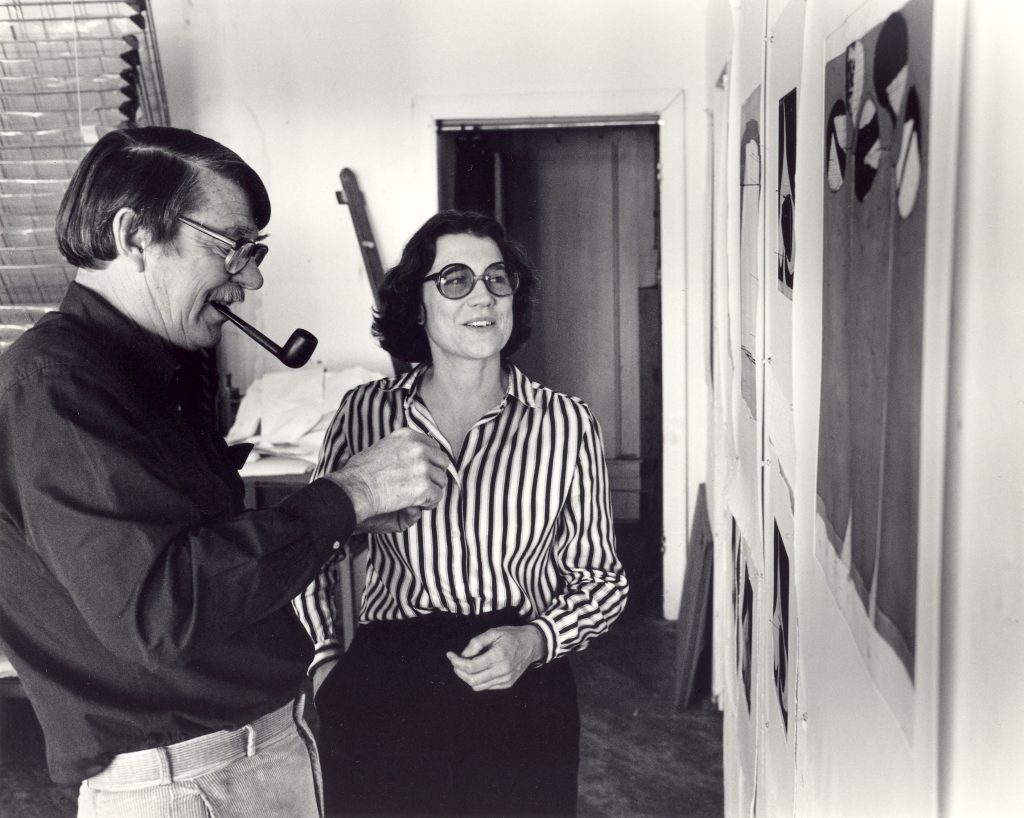

The Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo approaches Diebenkorn in regard to a potential retrospective exhibition. Director Robert T. Buck Jr. and assistant curator Linda Cathcart work closely with Diebenkorn and Phyllis to plan the show.

February: Gerald Nordland organizes a show of Diebenkorn’s monotypes, which opens at the Frederick S. Wight Art Gallery at UCLA; the show tours through university galleries across the country, ending at Stanford University in 1977. Diebenkorn discusses the monotypes with Henry Seldis at his studio on Ashland and Main:

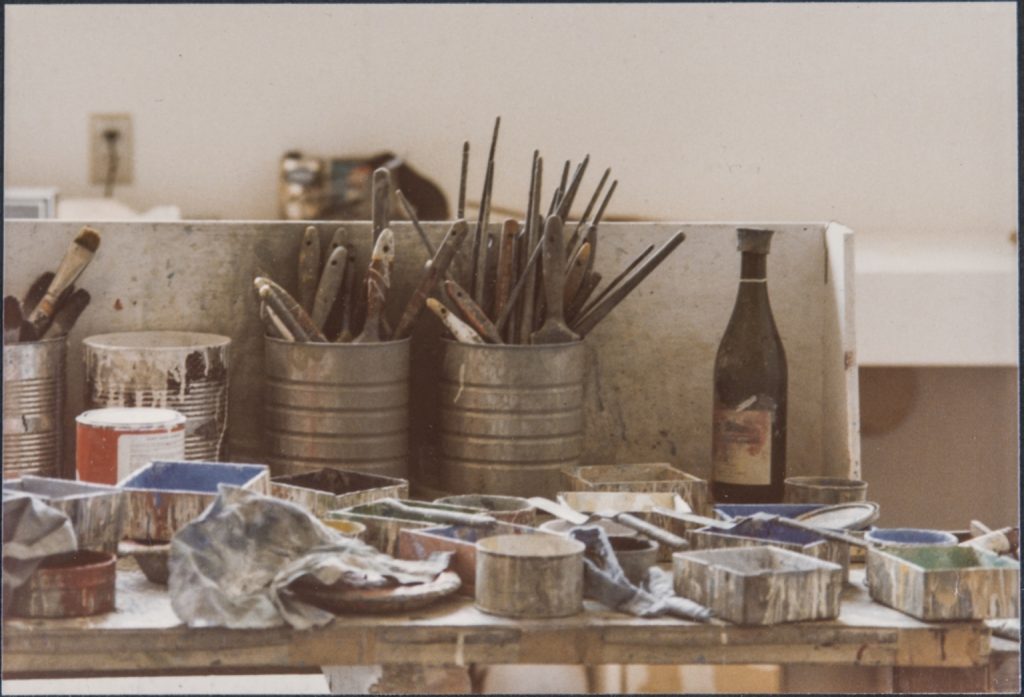

As abstract as they are, all my recent works are referential to observations in nature. In the late ’40s I tried to get all of that out of my work but now I just accept it. My work cannot be called nonobjective . . . For now, at least, I got this medium of work out of my system. . . . For me making drawings and paintings never exhausts themselves in this way. I am looking forward to moving into a new studio, made to my specification, soon, after nine years in this spacious old loft.293

27 February: Moves into his new studio at 2448 Main Street, in the Ocean Park neighborhood of Venice, just outside Santa Monica and a few blocks from his old studio at Ashland Avenue and Main Street.294 Brice says in a later interview with Jane Livingston, “I don’t know of any artist who was more responsive to his physical environment than Dick. If he moves down the block, it changes. He absorbed the aura of a place.”295

August: The Diebenkorns take a trip to Northern California; they raft down the Rogue River in Oregon with the McDonoughs, the Brices, and the Brices’ old friends, Charles and Alice Russell.296

11–20 October: Travels to Toronto, Buffalo, and New York City; meets with Robert T. Buck Jr. and sees the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in anticipation of the retrospective.297

12 November: Richard Diebenkorn: Paintings and Drawings, 1943–1976 opens at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery. To accompany the show, the Albright-Knox publishes a slender but important and widely circulated catalogue, with essays covering all three major periods and a historiographical account of his career: “Diebenkorn’s Early Years,” by Maurice Tuchman; “The Figurative Works of Richard Diebenkorn,” by Gerald Nordland; “The Ocean Park Paintings,” by Robert T. Buck Jr.; and “Diebenkorn: Reaction and Response,” by Linda L. Cathcart. Tuchman, a curator at LACMA, conducts extensive interviews with Diebenkorn for his essay on the artist’s early periods; he also interviews Phyllis, Gretchen, Paul Kantor, Elmer Bischoff, Frank Lobdell, Paul Harris, Gerald Nordland, Don Weygandt, Joann and Gifford Phillips, Walter Hopps, James and Barbara Byrnes, and Ray Parker.

The exhibition travels to the Cincinnati Art Museum (31 January–20 March 1977), the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (15 April–23 May), the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City (9 June–17 July), and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (9 August–25 September), and ends at the Oakland Museum of California (15 October–27 November). The Diebenkorns travel to Buffalo with their family, spending two weeks on the East Coast for the opening and attending each subsequent event except for the one in Cincinnati. Diebenkorn arrives early at each venue he visits to help with installation. About the retrospective, Phyllis said, “It was major . . . this one sort of made Dick national. He was pretty well-known in the art world, but this . . . did it.”298

November: Meets with Larry Rubin, a dealer at M. Knoedler & Co. in New York, to discuss the possibility of the gallery representing him.300

Begins making Ocean Park–like compositions on the lids of vintage cigar boxes, known as the cigar box paintings, which he gives to friends and family.

The couple celebrates New Year’s with the Brices and Ann Rosener at Ray Stark’s ranch in Los Olivos, Calif.; the friends will gather at the Stark Ranch for almost every New Year’s until 1990.

1977

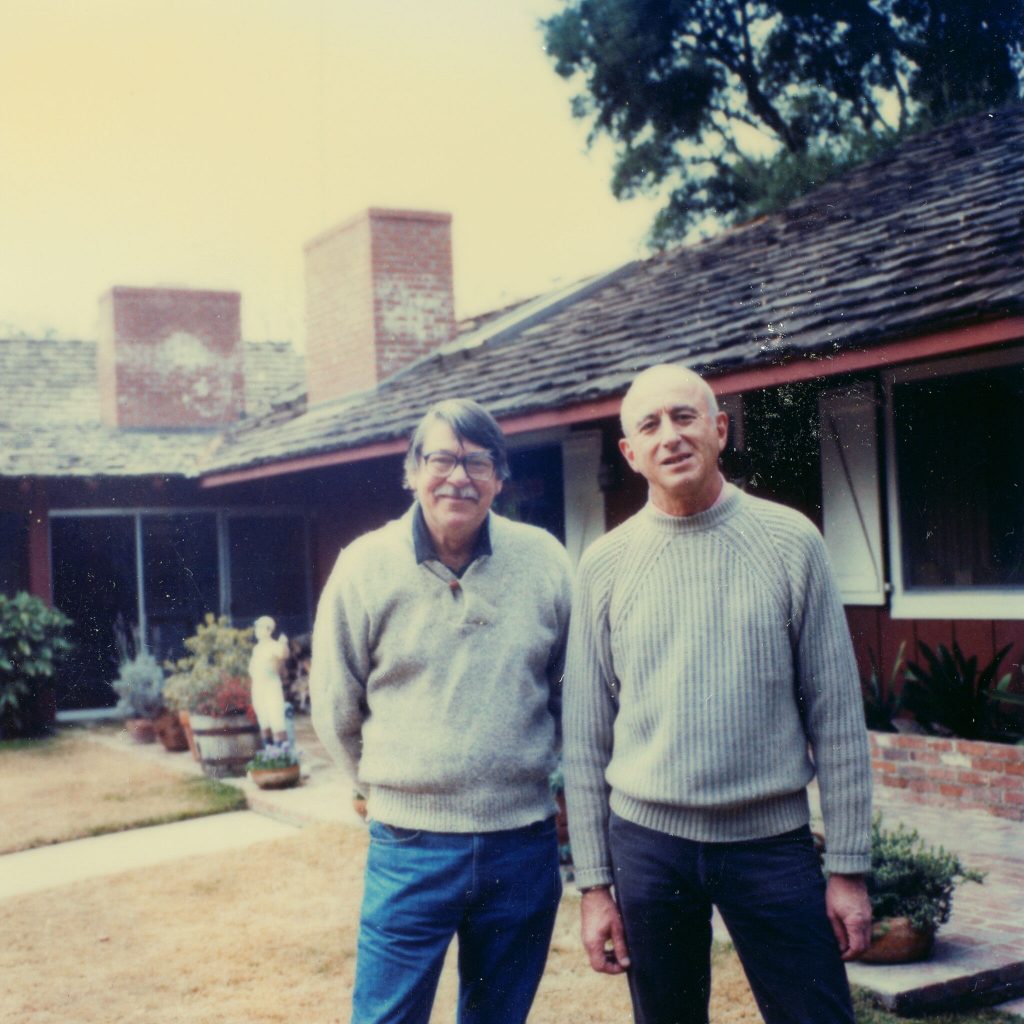

Decides to join the M. Knoedler and Co. gallery. The Diebenkorns become close friends and traveling companions with gallery director Larry Rubin and his wife, photographer Marina Schinz. A relationship with a dealer built on trust, respect, and general fondness is essential for Diebenkorn to work with a gallery. He will have fourteen solo exhibitions with the gallery over the next sixteen years, and Rubin and Knoedler will represent him until his death.

18 January–27 March: Black-and-white photographs by Diebenkorn are included in the LACMA exhibition Private Images: Photographs by Painters; they were taken in 1970, when the artist flew over Lower Colorado for the Bureau of Reclamation’s project.301 Diebenkorn’s statement is published on the exhibition poster:

These photographs are a record of an activity I’ve engaged in since I was quite young, and it’s one of those I assumed everyone did—at least occasionally. When I was a boy riding in the family car in the country (very bored) I aligned telegraph poles. As the car moved and the scene altered I might watch one in the foreground as it approached another in the middle distance and at the moment they coincided I would make a click inside my head. This became a game—basically quite simple—but lending itself to much greater complexity and difficulty as such as, where the situation permitted, stacking two poles to make a quite high one or the aligning of members in three or more levels of depth, the click always defining the critical instant when a notable visual phenomenon was occurring “out there.” The game has endless possibilities of variation such as when fence rails move like arrows or battering rams and strike stationary targets such as buildings or animals or simply form momentary crosses in the landscape. The game doesn’t require an automobile either, since while simply standing on the street an airplane may be seen, during that click, to be adhering to building face or to a telephone wire.302

11–18 April: Travels to Washington, D.C., with Phyllis for retrospective opening at the Corcoran Gallery, and spends a few days working with Jane Livingston on the installation of the show.

7 May–2 June: Attends the opening of first exhibition with M. Knoedler and Co., Richard Diebenkorn, in New York.

4–11 June: The Diebenkorns attend the Whitney Museum of American Art retrospective opening, of which Robert Hughes writes,

He is not, as the condescending tag once read, a California artist, but a world figure. He is not an avant-gardist either, and his work keeps alluding to its sources: the color to Bonnard and Matisse, the strong fractionally unstable drawing to Mondrian and Matisse again. Diebenkorn’s best paintings mediate between the moral duty to acknowledge the ancestor and the desire to claim one’s own experience as unique, unrepeatable. In short, he is a thoroughly traditional artist, for whose work the words “high seriousness” might have been invented.303

While in New York, the Diebenkorns see the Edgar Degas show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

9 August: Albright-Knox retrospective opens at LACMA.

September: Drives with Phyllis through the Southwest to meet with artist James Turrell. Turrell flies them over his Roden Crater piece in Arizona, as well as Lake Powell and the Grand Canyon. On their way to meet Turrell, they stop at Joann and Gifford Phillips’s home in Santa Fe, and visit the pueblos in Pecos National Historic State Park.

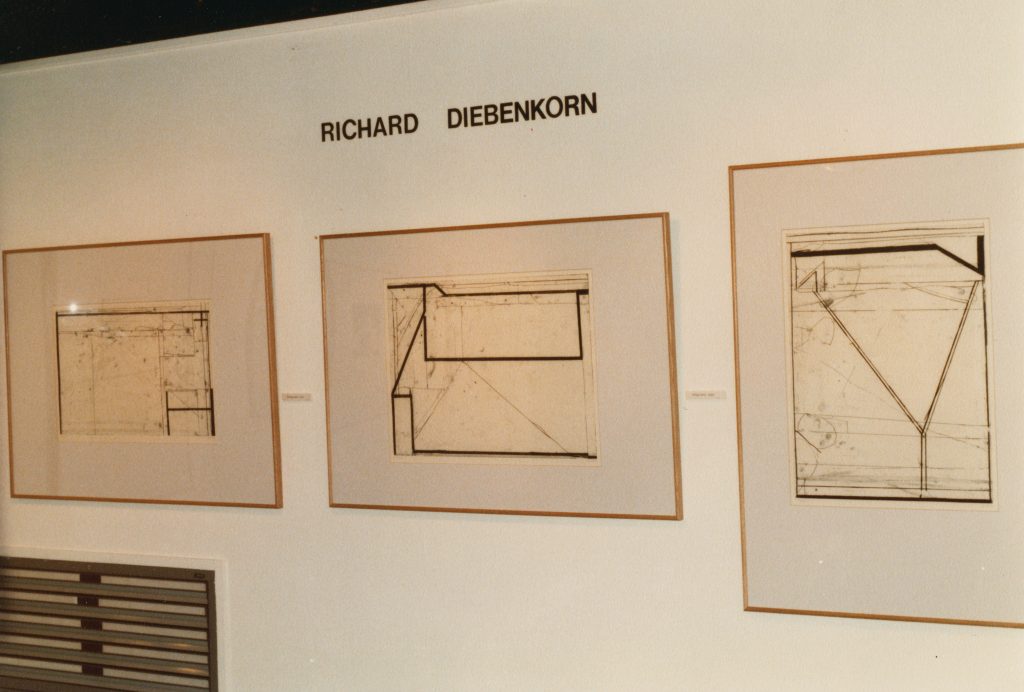

October: Travels to the Bay Area to work on a series of etchings with Kathan Brown at her print shop, Crown Point Press, where he worked in the early 1960s. Diebenkorn is one of the first artists that Brown invites to work at the shop after she transitions Crown Point into a publishing house as well as a press. He agrees, after only sporadically encountering the medium for over a decade, and will travel north almost every year until 1988 to work with Brown.

15 October: Final showing of retrospective opens at the Oakland Museum of California.

1978

6 February–22 May: Travels with Phyllis to Europe, where they house-sit for the Davenports near Aups, Provence, for several months, and visit Nice. Produces over a dozen works on paper but destroys them all, after deciding that the light in them is “too French” and inconsistent with his other works.304

March: Joan Mondale selects Berkeley #19 (cat. 1343) to hang in the vice president’s house.

Summer: Selected as the U.S. representative, with photographer Harry Callahan, for the 38th Venice Biennale. Linda Cathcart curates the biennale, and Nicole and Robert T. Buck are the U.S. commissioners.

26 June–5 July: Travels with Phyllis to Venice for the biennale’s 2 July opening.

16–21 August: Wins Edward MacDowell Medal from the MacDowell Colony in Peterborough, New Hampshire. Travels with Phyllis to Boston to accept the award.305

26 December 1978–3 January 1979: Works at Crown Point Press on Six Softground Etchings, in which he uses club and spade motifs.

Late 1970s: The Diebenkorns buy the lower unit of a large cedar-shingle duplex in the Elmwood neighborhood of Berkeley from their friend Flora Hitchcock, who continues to live in the upper apartment. The couple later buy the upper unit as well.

1979

20–29 January: Travels to New York, where he sits on the jury of the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation grant selection board.

30 April–13 May: Travels to New York to accept the Skowhegan Medal for Painting from the Skowhegan School of Painting in Maine; Andy Warhol, Carl Andre, and Christo are also recipients that year. The Diebenkorns visit Washington, D.C., to have tea with Joan Mondale and go to the National Gallery of Art. They return to New York, stopping at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Baltimore on the way. In New York Diebenkorn helps with the installation of a show of drawings at Knoedler and attends the opening. Looking around the gallery before the show opens, Diebenkorn says to critic Jeffrey Keeffe, “I’ve always wanted to paint a completely abstract painting, but I’ve never been able to.” 306

May: Elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Boston. Harry Callahan, Merce Cunningham, and George Segal are also elected this year.307

14–22 May: Travels from New York to Venezuela through the U.S. Embassy for the inauguration of a contemporary American art collection. William Luers, who traveled with the Diebenkorns to the Soviet Union in 1964 and is now the ambassador to Venezuela, organizes the trip. They visit Maracaibo and the oil fields, and see pre-Columbian art, the Ciudad Guayana, and the Ciudad Bolivar.

27 June–2 September: First show of intaglio works, Richard Diebenkorn: Intaglio Prints, 1961– 1978, opens at the Art Gallery at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Diebenkorn’s mother is frequently hospitalized in La Jolla; she moves to Santa Monica.

1980

Begins Clubs and Spades series of works on paper. The series breaks from the Ocean Park paintings and works on paper by featuring subjects that had long fascinated the artist: symbols and heraldic imagery.

11–22 January: Travels with Phyllis to New York for the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation jury.308

20 March–2 April, 25–29 April: Works on a series of prints at Crown Point Press.

June: Sees the Philip Guston retrospective exhibition at SFMOMA.

3–15 September: The Diebenkorns visit the East Coast with the Brices, William Brown, and Ann Rosener. Visit New York for the Picasso exhibition at MoMA, where curator John Elderfield gives them a private tour; see the Hopper exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. They also visit Philadelphia to go to the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Merion, Pennsylvania, to go to the Barnes Foundation.

While arranging the details of the trip in a previous letter to John Elderfield, Diebenkorn accepts Elderfield’s offer of a tour of the Picasso exhibition. He also recommends that Elderfield visit his upcoming November show at Knoedler, as he will see his work “much changed.” 309

15 October–4 November: The Diebenkorns tour the Mediterranean on a Stanford University– organized trip with classics professor Marsh McCall, visiting Athens, Malta, Porto Empedocle in Sicily, Tunis, and Naples in southern Italy. Diebenkorn is pleased with the visit to Malta, as it allows him to pursue his interests in the Crusades and related medieval icons and figures, like the Cross of Saint John.

7 November–2 December: Attends the opening of Richard Diebenkorn: Recent Work at Knoedler. Hal Foster reviews for Artforum,

Diebenkorn seems ambivalent; he wants both [abstraction and representation], sees them as opposed, and so ends up with neither. Once, perhaps, to achieve non-representational painting (which, I would argue, is the real painting of and about representation), it was necessary to abstract, as Mondrian abstracted a tree or a pier into a system of lines. It is not so now. I do not mean that Diebenkorn does this. But there is a diagrammatic quality to the work. The line is compositionally descriptive of form, and so related to drawing in the old sense.310

December 1980–January 1981: Included in the Blum Helman Gallery show Three by Four in New York with Ellsworth Kelly, Roy Lichtenstein, and Frank Stella. In a 1981 review for Artforum, Carrie Rickey writes,

With Diebenkorn, as with Reinhardt, there are moments when you get fed up with the trademark look, frustrated that this artist is redundant and facile, that he has only one idea. But it’s artists like Diebenkorn who gently teach you that it is in the subtle differences between similar images that the understanding of how things work takes place.311

1981

29 January–8 February: Travels to New York for the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation jury; also sees Tony Berlant’s show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and visits the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the CooperHewitt National Design Museum.

13–21 April: Works on a series of prints at Crown Point Press. Attends the book signing for Richard Diebenkorn: Etchings and Drypoints, 1949–1980, the catalogue for a retrospective exhibition of Diebenkorn’s intaglio prints, published by Houston Fine Art Press. Richard Newlin, director of the press, attended Stanford, where he was an assistant to Nathan Oliveira.

Completes no paintings this year.

1982

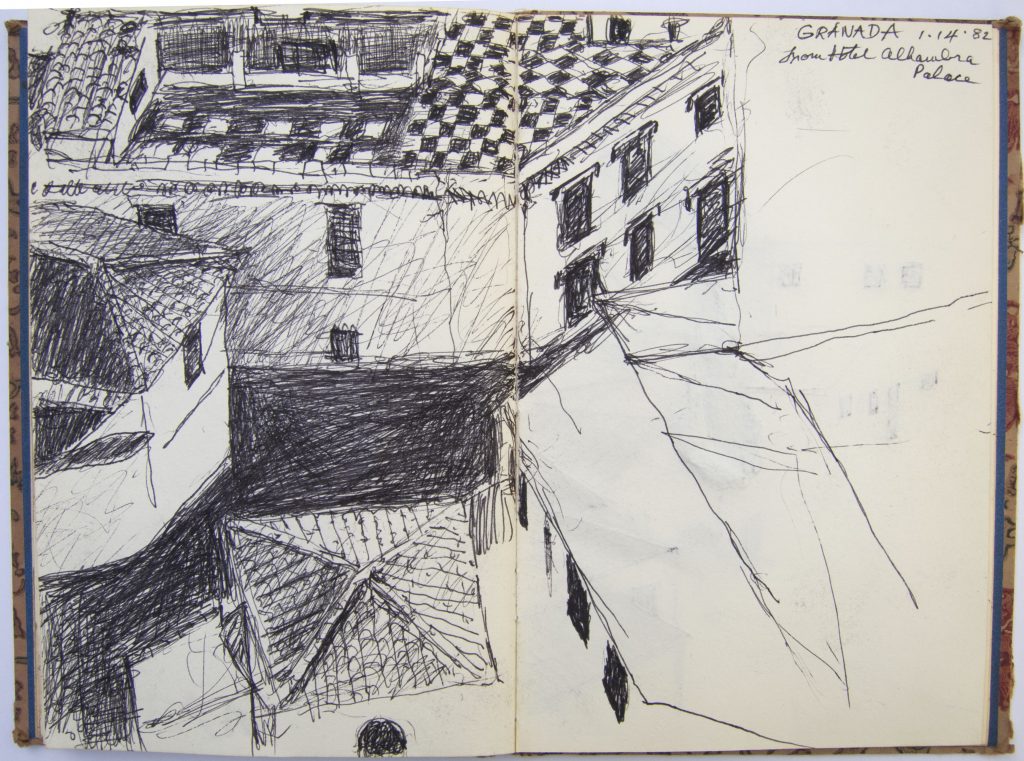

4–11 January: Travels with Phyllis to New York for the opening of the exhibition of Clubs and Spades drawings at M. Knoedler and Co. The show is widely reviewed, and the vocabulary used to describe the new shapes varies. Robert Hughes writes for Time Magazine, discussing

a curious motif Diebenkorn refers to as his “ace of spades,” and which does resemble the black pip on that card pushed and pulled out of shape. It is Diebenkorn’s way of breaking up the remote geometry of the Ocean Parks; one no longer sees a distant “view” of a whole terrain, but moves closer, toward this lobed and writhing emblem which suggests either a body or still life.312

In a later study, Curtis Brown, then a graduate student at USC’s Museum Studies Program, will write,

Referred to by Diebenkorn as a “surprise” element in his work, the clubs-and-spades motif, in fact, springs from interests that originated in his childhood. Although he has spoken of these symbols as autobiographical and wishes for their meaning to remain private, the history and function of such symbols may be a step toward an explanation of their presence in Diebenkorn’s art.

Rather than examining clubs and spades alone, we should consider them instead as simply the most visible component of what might be termed Diebenkorn’s “heraldic” imagery, a range of references that includes an assortment of shapes drawn from the iconography of knights, chivalry and heraldry of the Middle Ages. A fascination with the subject seems to have never left Diebenkorn, and so it may be the overall heraldic connotation of playing-card icons, rather than their reference to the game of playing cards, that accounts for the artist’s enduring delight in depicting them.313

12 January–8 February: The Diebenkorns travel from New York to Spain and Morocco with Larry Rubin and Marina Schinz. In Spain, they visit Granada; and in Morocco they drive through the Atlas Mountains. Also travel to Southern France and visit their friends the Davenports.

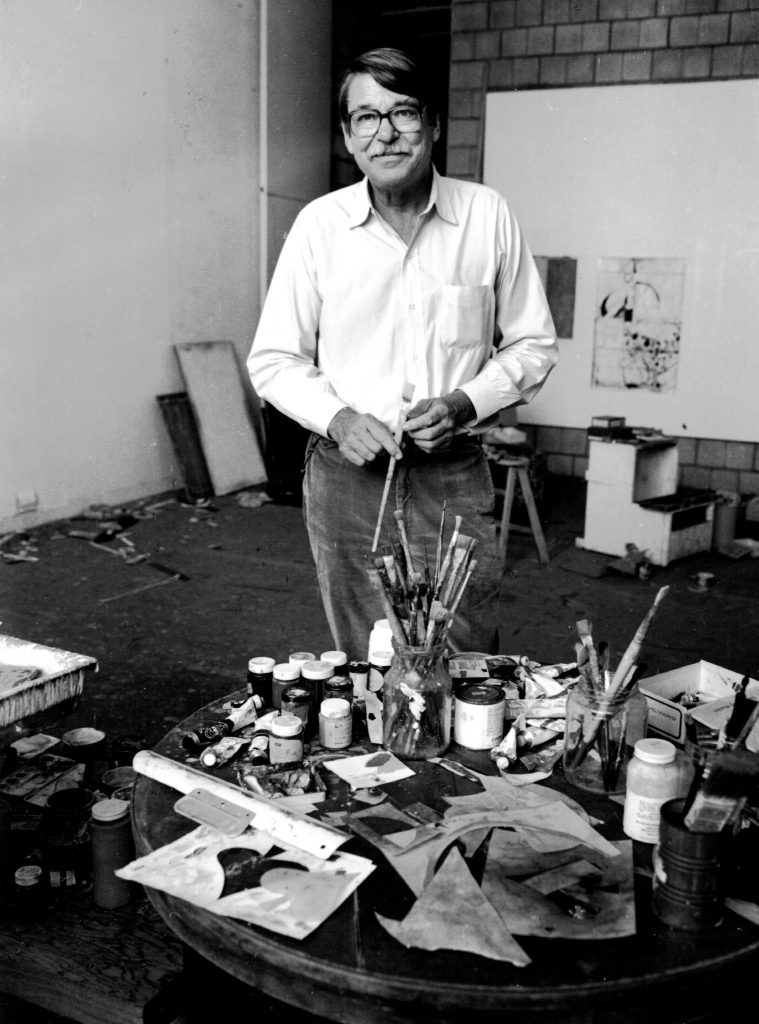

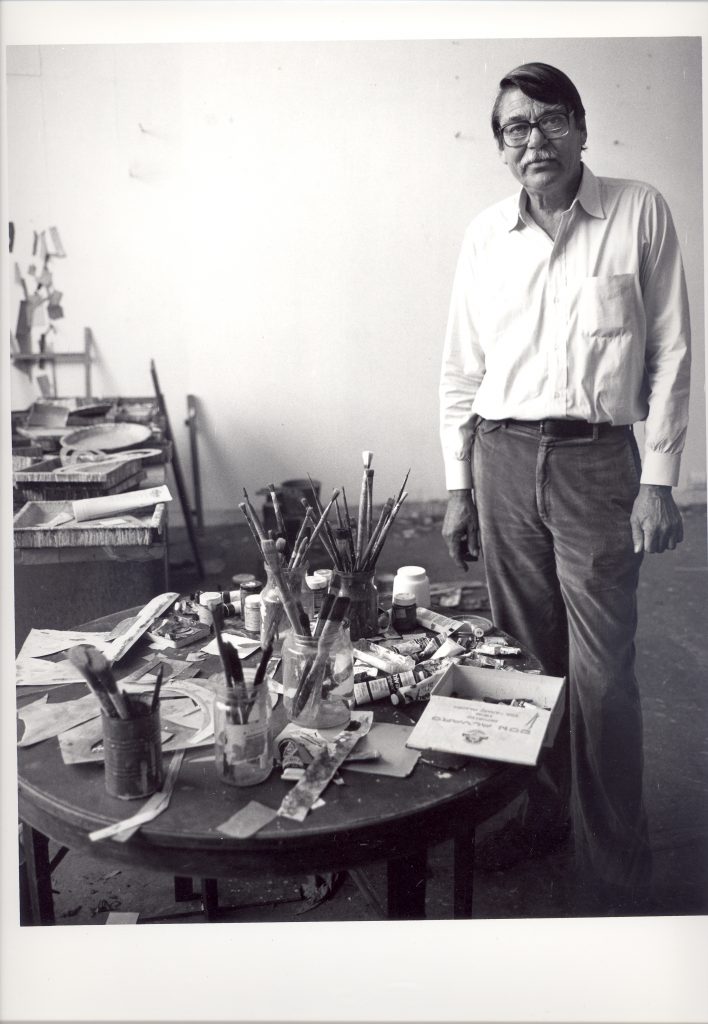

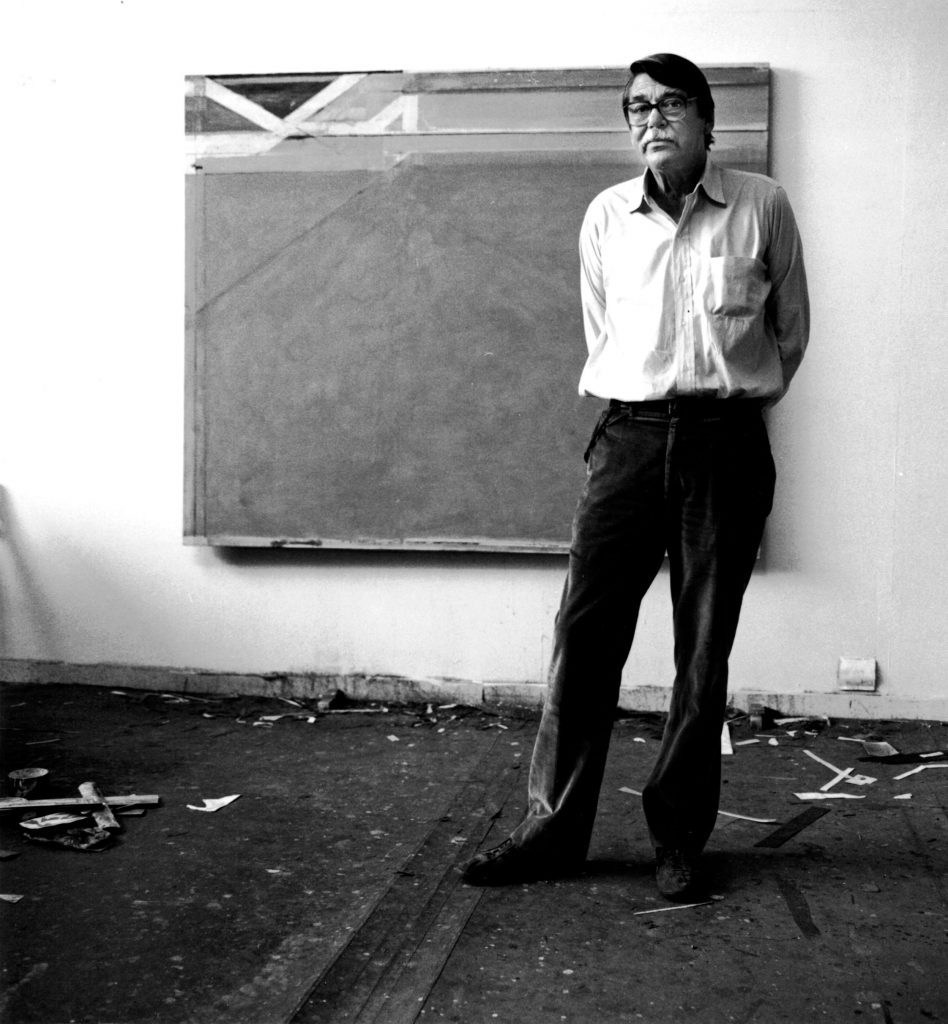

5 March: Hans Namuth and his wife visit the Diebenkorns; Namuth photographs Diebenkorn in his Ocean Park studio.

5–20 May: Works at Crown Point Press.

Summer: Works with Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles to produce a print for the Museum of Contemporary Art’s Portfolios Project. The portfolio, Eight by Eight to Celebrate the Temporary Contemporary, organized by Sam Francis and designed by Joseph Kosuth, is released in August. It includes prints by Francis, Robert Rauschenberg, Niki de Saint-Phalle, Ellsworth Kelly, David Hockney, Jean Tinguely, and Andy Warhol. Untitled ( from Club/Spade Group ’81–’82) is Diebenkorn’s first edition with Gemini G.E.L.

12 June: Receives an honorary doctor of fine arts degree from Occidental College in Los Angeles; in conjunction, the college hosts a small retrospective exhibition.

2–12 August, 18–19 October: Works at Crown Point Press.

12–20 December: Travels to New York. Elected academician at the National Academy Museum and School in New York.314

Moves away from using club and spade motifs in the works on paper, but will continue to use these forms in his printmaking. Returns to modified Ocean Parks in the works on paper.

In 1981 I did accept both a theme and a motif in the form of the black playing card pips, clubs and spades. I had used these signs in my work almost from my beginnings, but always peripherally, incidentally, and perhaps whimsically. So at this point I dealt with them directly—as theme and variation. I discovered that these symbols had for me a much greater emotional charge than I realized EXPECTED. I had intended to involve myself with them only briefly but found that their impetus kept me with them for almost a year and a half. This imagery finally exhausted itself and I have returned to a “relational” mode.315

Completes no paintings for a second successive year.

1983

22–26 January: Visits San Francisco to sign prints at Crown Point Press; sees Frank Lobdell’s show at SFMOMA, as well as works by Elmer Bischoff, James Weeks, and David Park at John Berggruen’s gallery.

1–11 February: Travels to New York for the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation jury. From New York the Diebenkorns fly to Germany; they visit Düsseldorf and Frankfurt. The trip is partially motivated by Diebenkorn’s interest in researching his last name and family history. He finds a distant relative in Hamburg who remembers Diebenkorn’s great-grandfather leaving for America.317

10 March–1 May: Attends the opening for Richard Diebenkorn: Paintings and Drawings from the Ocean Park Series at the Newport Harbor Art Museum, Newport Beach, Calif.

11 May–11 June: Attends the opening for Richard Diebenkorn: Works on Paper, 1970–1983 at John Berggruen Gallery in San Francisco.

13 May–17 July: George Neubert organizes Richard Diebenkorn: Paintings, 1948–1983 as a part of the Resource/Response/Reservoir exhibition program at the SFMOMA. Diebenkorn helps Neubert hang the show and attends the opening.318

July: Resigns from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation jury. Feels that during his tenure he attempted to broaden the geography of the artists receiving fellowships and support his peers in California.319

Fall: Participates in Art for a Nuclear Weapons Freeze: An Exhibition and Auction, organized by the National Weapons Freeze Campaign.

September: Writes a statement for the exhibition Drawings, 1974–1984, organized by Frank Gettings at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C.

My reasons for doing “drawings” (many of them are fully developed paintings) are, roughly, twofold. My drawings often begin as sketchy explorations of ideas, which then hook me in further, and then complete, development. This activity, up to the point where it becomes for me a serious work, is related to my larger oil on canvas pieces and is a kind of tryout or rehearsal of general possibilities. It ceases to be this, however, at the point of becoming an independent work.

The other reason, which somehow in no sense excludes the first, is my need to do relatively small works, independent of others and complete in themselves. But a small canvas usually becomes for me an unfeasible miniature. Paper, however, I find is something else, lending itself to the different scale of the small size. It is almost as though if I can call my work a large drawing instead of a small canvas, it becomes possible.

My drawing sources over the past fifteen years are various. Most of that time it has been in terms of “Ocean Park” ambience consisting of relatively pure painting and, in spite of atmospheric and visual overtones, strictly relational, dependent on no theme or motif. 320

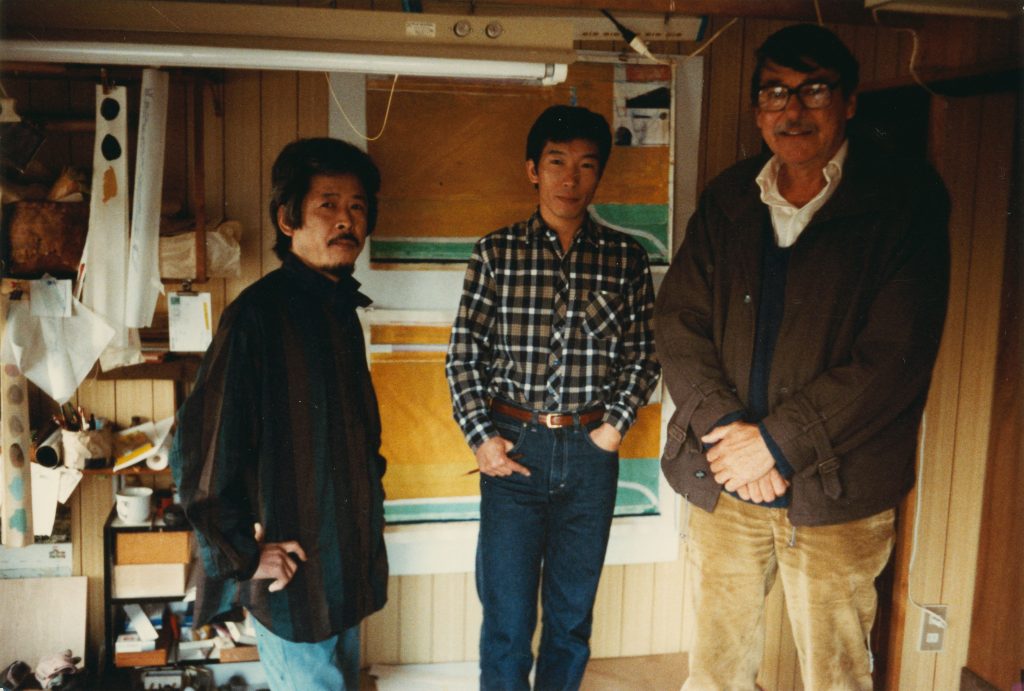

8–21 October: Makes first of two trips to Kyoto, Japan, as a part of the Crown Point Press program to bring artists to work with wood-block printmaker Tadashi Toda. Kathan Brown and her husband, artist Tom Marioni, and Crown Point printer Hidekatsu Takada are there throughout their visit. Works on Ochre and Blue. Phyllis, who joins Diebenkorn on both trips, says:

It was one of the three or four high points of our lives . . . partly because it was such a great surprise. Neither one of us had either thought about Japan or thought we wanted to go there or anything, and then it happened and we went and it was so exciting. It was really a delight.321

2–9 November: Travels to New York; sees a drawing show at MoMA with John Elderfield.

For the third successive year, completes no paintings.

1984

Begins painting again, with Ocean Park #126 (cat. 4580), utilizing tripartite banding and diagonal. The Ocean Park paintings that follow break away from the common structure of the works before 1981, with more horizontal canvases and compositional elements across the plane, not only concentrated on the upper edge of the pieces. The works lean toward the darker and more muted end of the spectrum.

12–31 May: A new show of drawings opens at M. Knoedler and Co., New York. Donald Kuspit writes for Artforum,

Where Willem de Kooning refuses the geometrical option, Richard Diebenkorn takes it, but not with the rigor of Mondrian: within Diebenkorn’s “primitive” frame, any configuration is possible. And whereas de Kooning tries to break the frame however much he implicitly accepts it (a reluctant acceptance), Mondrian and Diebenkorn manipulate whatever comes within its boundaries into a devious echo of it.322

Motherwell writes Diebenkorn to congratulate him on a “stunning” show.

August: The artist’s mother, Dorothy Diebenkorn, dies.

Begins large series of lithographs at Gemini G.E.L., which he will complete in January 1985.November: Gerald Nordland begins work on his monograph on Diebenkorn. Initially Nordland proposes the idea of a biography, but the artist is opposed to a piece that focuses on his personal life. Upon his insistence, Nordland’s book charts Diebenkorn’s work as an artist. The Guggenheim Foundation supports the project, and Diebenkorn and Phyllis review multiple drafts of the text and selected illustrations.323

1985

January: Susan Larsen organizes Sunshine and Shadow: Recent Painting in Southern California. Larsen points out Diebenkorn’s involvement in the life of younger Los Angeles artists.

10 May–1 September: George Neubert organizes Richard Diebenkorn: An Intimate View, a show of Diebenkorn’s cigar box paintings, at the Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery in Lincoln, Nebraska, bringing all thirteen of these paintings together for their first public exhibition. The show opens at the Brooklyn Museum later this year. Dore Ashton writes in the catalogue essay,

Over the years Diebenkorn has been more, or less, specific. When he was more specific, he recorded certain outer stimuli, such as windows, verandahs, cups, knives, and human presences. When he was less specific, as in the Ocean Park series, oblique rather than overt references prevailed, and these outer stimuli were subsumed by intuitions of the universe . . . that required intense concentration, intense questioning to find the right form, the transmissible experience. The nature of this experience in the Ocean Park works eludes prosaic language, and can be related more to music and poetic measure than to figurative art. Diebenkorn’s painting surfaces, even those as finite as cigar-box lids, are always analogues. I think of Wallace Stevens who . . . wrote: “There is always an analogy between nature and the imagination, and possible poetry is merely the strange rhetoric of that parallel . . .”325

12 May: Travels to New Mexico with Phyllis to receive an honorary doctorate in the fine arts from the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

16 May–11 June: The Diebenkorns visit Prague to see their friend William Luers, now ambassador, and his wife, Wendy. Afterward they travel to France to stay with the Davenports near Aups, in Provence.

18–21 September: Visits New York to see the Kurt Schwitters show at MoMA, organized by John Elderfield.

30 September–15 October: Works on drypoints at Crown Point Press; sees Wayne Thiebaud’s show of prints at the Crown Point Press gallery.

November: Awarded a chair in the American Academy of Arts and Letters, into which he will be inducted on 21 May 1986.326

2 November–5 December: Richard Diebenkorn opens at Knoedler in New York; this is the first annual show to include paintings since 1980.

The Diebenkorns travel to New York for the opening, and see a show of Frank Stella’s work.

December: Becomes the first visiting artist at the new Santa Fe Institute of Fine Arts, founded by Pony Ault and William Lumpkins; he and Phyllis will remain involved with the program. The couple spends Christmas with Joann and Gifford Phillips in Santa Fe.

Completes final Ocean Park painting.

1986

The Diebenkorns decide to leave Santa Monica. They begin driving through California, Montana, and the Southwest, looking for a place to settle. The two want a property away from urban centers and an older home with character; the two enjoy a house in which its own “pentimenti” are visible. Phyllis recalls,

I was done with LA long before he was. . . . There were things I loved about it, but I never really felt that I belonged there. . . . Somehow, when we came . . . [in 1966], mainly because of Shirley and Billy, everybody we knew was somehow involved with movie-making. It was the money that was buying art. It was the eager people that were supporting the museums and the showy people that were buying the nice furniture and paintings.

I loved the beach, but I never really loved the endless same weather and the smog and the traffic and all that. I never felt at home there the way I felt in Berkeley. . . .

I think when he absorbed all there was for him in LA then he didn’t know why he was there anymore.328

Diebenkorn will later say in an interview for CBS’s Sunday Morning with David Browning,

In the last year, I felt that each time I went out in the car to west Los Angeles for errands or whatever, every trip I made, it was that much worse. I felt that it was—I was more hemmed in, more closed in on . . . 329

27 January–9 February: Works on an edition at Crown Point Press.

26 April–31 May: Exhibition New Prints by Richard Diebenkorn and Others is held at Crown Point Press in New York.

8–18 September: Works at Crown Point Press.

1987

18–31 January: Travels to the East Coast for a meeting at the press offices of Rizzoli, the publisher of Nordland’s monograph. Visits the National Gallery of Art and the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., meeting with Jack Cowart, Ruth Fine, and Jane Livingston, with her future husband Lisle Carter. In New York visits the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Van Gogh show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, MoMA, and galleries in SoHo, and hears the Emerson String Quartet play Beethoven quartets at Alice Tully Hall.

3–7 March: Attends a National Academy meeting in New York; has dinner with Wolf Kahn, Emily Mason, and Wayne Thiebaud. Sees the Paul Klee show.

10 April: Travels to Santa Cruz Island with Phyllis to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the Stanton family’s presence on the island.

15 April–19 May: Travels to Frankfurt.

14 June: UCLA awards Diebenkorn the UCLA Medal. At the commencement ceremony, his simple acceptance speech, “Thank you,” receives a standing ovation.330

12–26 July: The Diebenkorns depart on their California and Nevada “House Finding Trip.” Beginning in Los Olivos, they drive through Springville, Paso Robles, Sonora, Reno, and Berkeley, ending up in Healdsburg, in the Alexander Valley—recommended by the McDonoughs—in Northern California.331 Diebenkorn falls for a simple 1878 Victorian across from a vineyard, looking up past the foothills to Mount Saint Helena; they buy the house on 25 July. The previous owner, Billy Pearson—a jockey and antiques dealer in the Bay Area—slowly and painstakingly renovated the house, after moving the building back from the road. The Diebenkorns spend the Summer working with designer Jay Claiborne to build a guest house—styled after the guest houses on Santa Cruz Island—and to convert the garage into a studio, with clerestory windows to let in the northern light. The designer installs a state-of-the-art lighting system in the studio, which goes unused; instead the artist relies on dome-shaped clip lights.

Fall: Dan Hofstadter writes “Almost Free of the Mirror” for the New Yorker, an intimate and revealing profile. Diebenkorn comments, “A way is just what I don’t want. With each new painting, I find a way all too soon. And that’s when the trouble starts.” 332

8–29 October: Kathan Brown invites Diebenkorn to Japan to work on a second edition of woodblock prints. They join the Brices in Kyoto, where Bill Brice also was producing a woodblock with the Crown Point Press program. The two couples, with Brown, Tom Marioni, and project coordinator Hidekatsu Takada, travel together between the two artists’ residencies. Afterward Diebenkorn settles into Tadashi Toda’s shop and completes Blue with Red and Double X, remarking that the “intent of the process . . . was not simply to reproduce or copy but to ‘go’ with the inevitable variances which occur between the ‘original’ and the developing print.” 333

4–28 November: Richard Diebenkorn opens at M. Knoedler and Co. in New York. The Diebenkorns attend the opening. They meet with John Elderfield and Gifford and Joann Phillips, visit galleries, and go to the Guggenheim Museum.

14 November: The Diebenkorns spend their first night at the house in Healdsburg. They begin splitting their time between Santa Monica and Healdsburg until the house on Amalfi Drive is sold.

Two monographs on Diebenkorn’s art and career are published; Diebenkorn and Phyllis contribute extensively to the creation of both volumes. In Richard Diebenkorn (Rizzoli), Gerald Nordland uses his extensive collection of notes from decades of discussions with Diebenkorn to write the text, which is reviewed at numerous stages by the artist and his wife. Richard Newlin, of Houston Fine Art Press, publishes a volume of Diebenkorn’s works on paper from the Ocean Park series. Diebenkorn gives Newlin access to his library of reproductions and to previously unpublished works from his studio.

293. Richard Diebenkorn quoted in Henry J. Seldis, “Diebenkorn Monotypes at Wight Gallery,” Los Angeles Times, 17 Feb. 1976. Copyright © 1976. Los Angeles Times. Reprinted with permission.

294. The ground unit, 2444, is tenant occupied; Diebenkorn’s studio is 2448.

295. Bill Brice, unpublished interview with Jane Livingston, May 1996, RDFA.

296. Datebook, 1976.

297. Ibid.

298. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.

300. Datebook, 1976.

301. One of these photographs is reproduced here from the original slide, on p. 176. See also cat. 4025.

302. Richard Diebenkorn, statement on exhibition poster for Private Images: Photographs by Painters (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1977).

303. Robert Hughes, “California in Eupeptic Color,” Time, 27 June 1977, 58.

304. Gerald Nordland, comment in a draft of Nordland’s Richard Diebenkorn, 1987, RDFA.

305. Datebook, 1978.

306. Richard Diebenkorn quoted in Jeffrey Keeffe, “Reviews: Richard Diebenkorn, M. Knoedler,” Artforum, Sept. 1979, 79.

307. New members of the American Academy are typically elected in the Spring and inducted the following Fall.

308. Datebook, 1980.

309. Diebenkorn to John Elderfield, 19 Aug. 1980, [John Elderfield files].

310. Hal Foster, “Reviews: Richard Diebenkorn,” Artforum, Feb. 1981, 75.

311. Carrie Rickey, “ ‘Three by Four,’ Blum Helman Gallery,” Artforum, Mar. 1981, 85.

312. Robert Hughes, “A Geometry Bathed in Light,” Time, 25 Jan. 1982, 46.

313. Curtis Brown, “Heraldry and Playing Cards in Richard Diebenkorn’s Art,” in Richard Diebenkorn: Works on Paper from the Harry W. and Mary Margaret Anderson Collection (Los Angeles: Fisher Gallery, University of Southern California, 1993), 22.

314. The National Academy Museum and School in New York is also known as the National Academy of Design.

315. Richard Diebenkorn statement in Frank Gettings, Drawings, 1974–1984, exh. cat. (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1984), 77. Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution. Text edits from Diebenkorn’s copy of the publication, Diebenkorn’s own marginalia, RDFA.

317. Diebenkorn, interview with Larsen, 1 May 1985. Diebenkorn was told, perhaps incorrectly, that the name derives from the Swedish word for stacks of grain.

318. Datebook, 1983.

319. Diebenkorn to John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, draft, 1983, RDFA.

320. Diebenkorn statement in Gettings, Drawings, 77. Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution.

321. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.

322. Donald Kuspit, “Richard Diebenkorn, Knoedler Gallery,” Artforum, Nov. 1984, 102.

323. Nordland, Richard Diebenkorn (2001), 215–18.

325. Dore Ashton, in Small Paintings from Ocean Park (Houston: Houston Fine Art Press; San Francisco: Hine, 1985), n.p.

326. The American Academy of Arts and Letters was the upper echelon of the National Institute of Art and Letters; shortly after Diebenkorn’s advancement the members voted to merge the two chambers.

328. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.

329. Richard Diebenkorn, “Splendid Solitude,” interview with David Browning, Sunday Morning, CBS, 8 Jan. 1989.

330. Gretchen Diebenkorn Grant, in conversation with the author, n.d., RDFA.

331. The Diebenkorns also visited Montana, Los Olivos, Napa, Sonoma, and San Ysidro.

332. Diebenkorn quoted in Hofstadter, “Almost Free of the Mirror,” 59.

333. Diebenkorn quoted in Contemporary Wood Block Prints from Crown Point Press (Fort Meyers, Fla.: Edison Community College, 1991), n.p.