1956

January: Critic Hubert Crehan, a former student of Clyfford Still at the CSFA, writes the article “Is There a California School?” for Art News, disavowing the existence of a California school or, as the French critic Michel Tapié called it, êcole du Pacifique.155 Diebenkorn’s Berkeley #42b (cat. 1479) is reproduced in the article. In response, the Oakland Art Museum hosts “California School, Yes or No?,” a forum organized by curator Paul Mills, in which the Bay Area arts community comes together to discuss, and generally reject, the existence of a San Francisco school.156

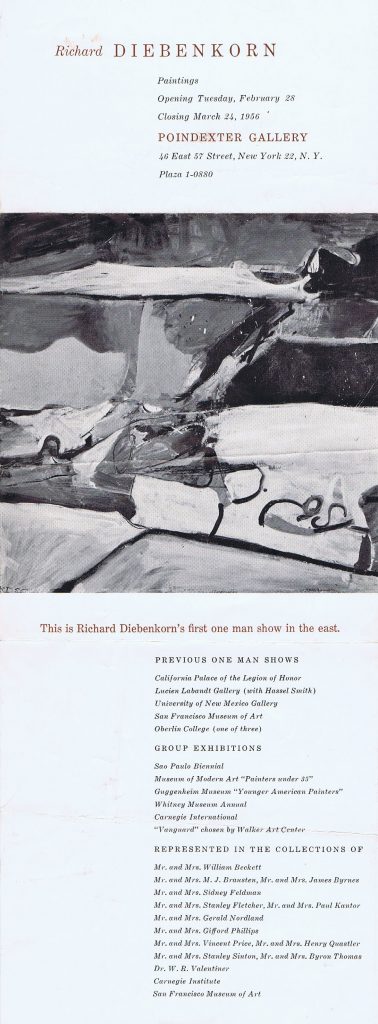

28 February–24 March: Richard Diebenkorn at Poindexter Gallery at 46 East 57th Street is the artist’s first solo show in New York. Poindexter will represent Diebenkorn until 1971; as part of their agreement Paul Kantor is allowed to sell the Diebenkorn works he has in his possession and represent him for a period of time in Southern California.157 Stuart Preston of the New York Times calls Diebenkorn a “rising star” of Abstract Expressionism: “His compositions . . . resemble aerial photographs of a big varied landscape with shore-line mountains, cliffs and fields, the contours, perhaps, of California, where this painter lives and has made his reputation. For all its considerable energy and invention, Diebenkorn’s work remains strangely impersonal or, rather, remotely personal.”158

The show is also reviewed in Arts Magazine, where Diebenkorn’s use of a raised perspective is again mentioned, and by Dore Ashton in Arts & Architecture.159

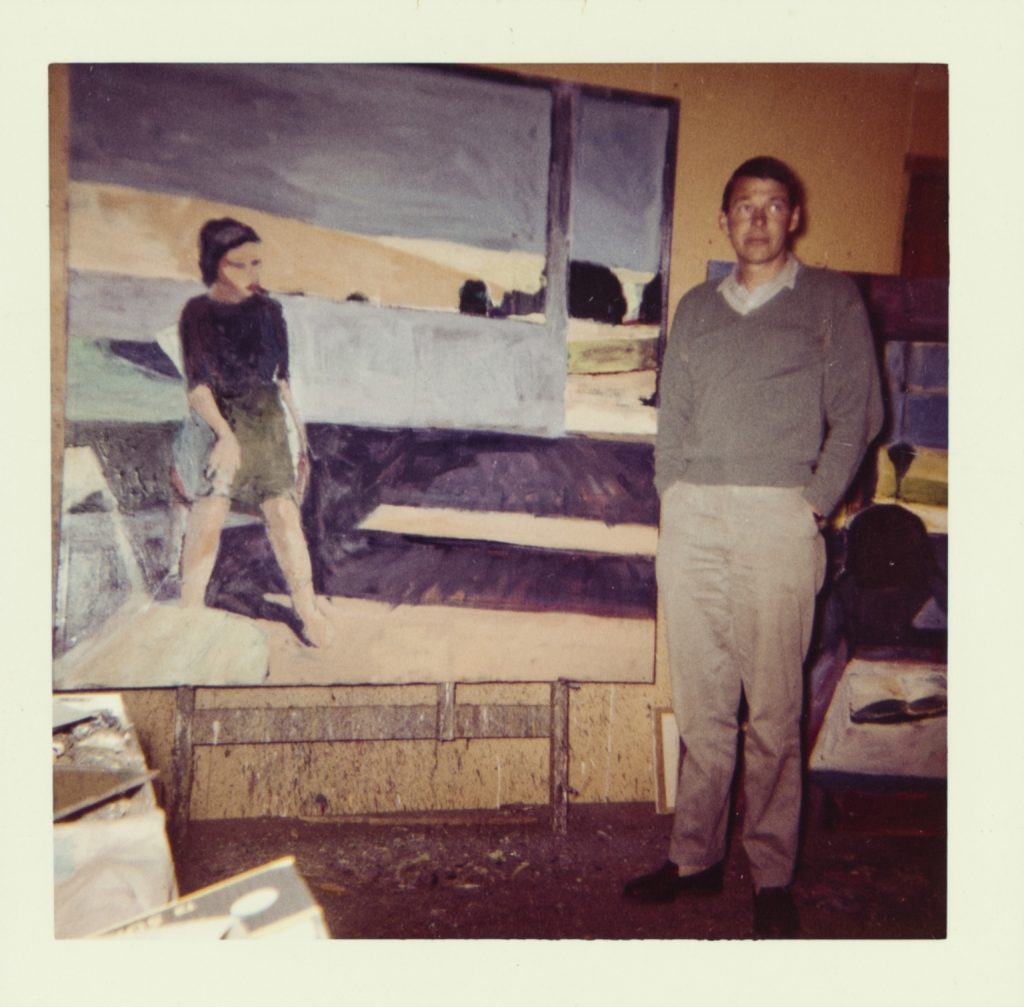

Diebenkorn completes his Berkeley series and turns his full attention to representational painting and drawing. “I was encumbered with style and too concerned with style,” he says. “There were a good many things I wanted to say—to talk about—that a more strict style prevented. My painting was too inbred.

Representation was a challenge I hadn’t had before.” 160

Art scholar Caroline Jones comments, “Diebenkorn took the largest risk of any of the artists by turning to figuration for he had attracted considerable national recognition with his abstract work.”162

29 March–6 May: Wins the Seventy-Fifth Commemorative Artist’s Council Award for Berkeley #66 (cat. 2099) at the SFMA’s Seventy-Fifth Annual Painting and Sculpture Exhibition of the San Francisco Art Association.

Summer: Elmer Bischoff, who had been living and teaching in Marysville, Calif., for a number of years, returns to the Bay Area and actively joins the drawing sessions, at which Diebenkorn, Park, and Bischoff are the core group.163 Theophilus “Bill” Brown, who moved to Davis, Calif., with Paul Wonner in 1956, will later note that “David, Elmer, and Dick were very important to each other, in a way the rest of us in a sense were very peripheral.”164

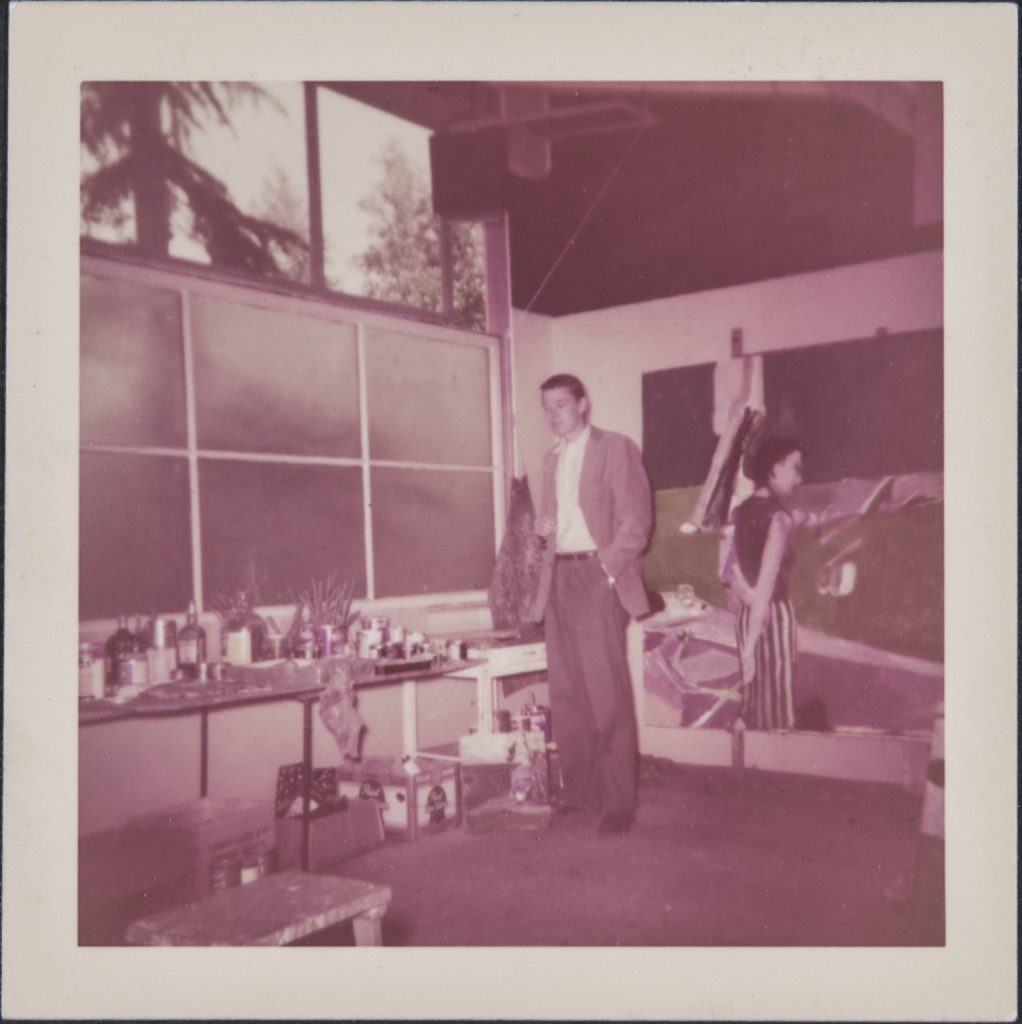

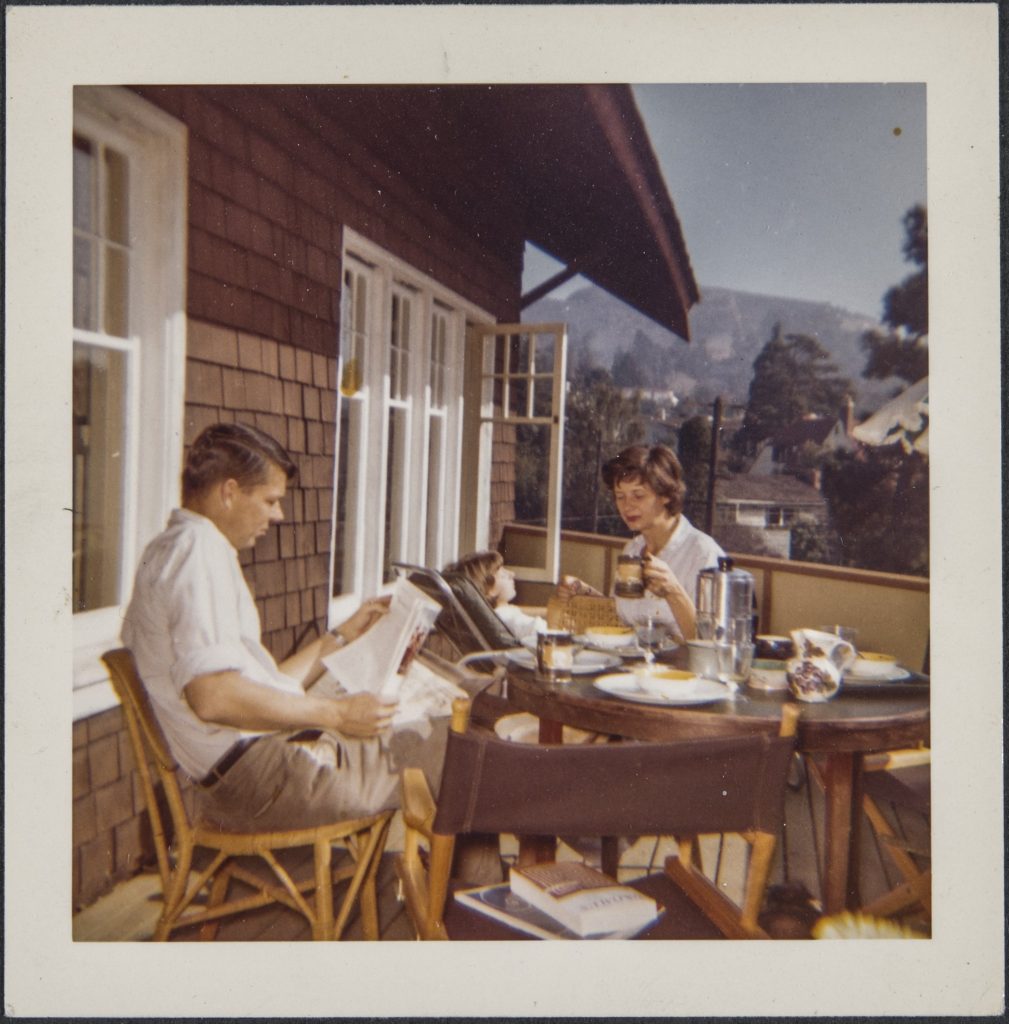

June: The Diebenkorns buy a house at 217 Hillcrest Road in the Berkeley Hills; Diebenkorn spends the next two months building a freestanding studio in the backyard. The artist will routinely carry his paintings back and forth between the studio and house.

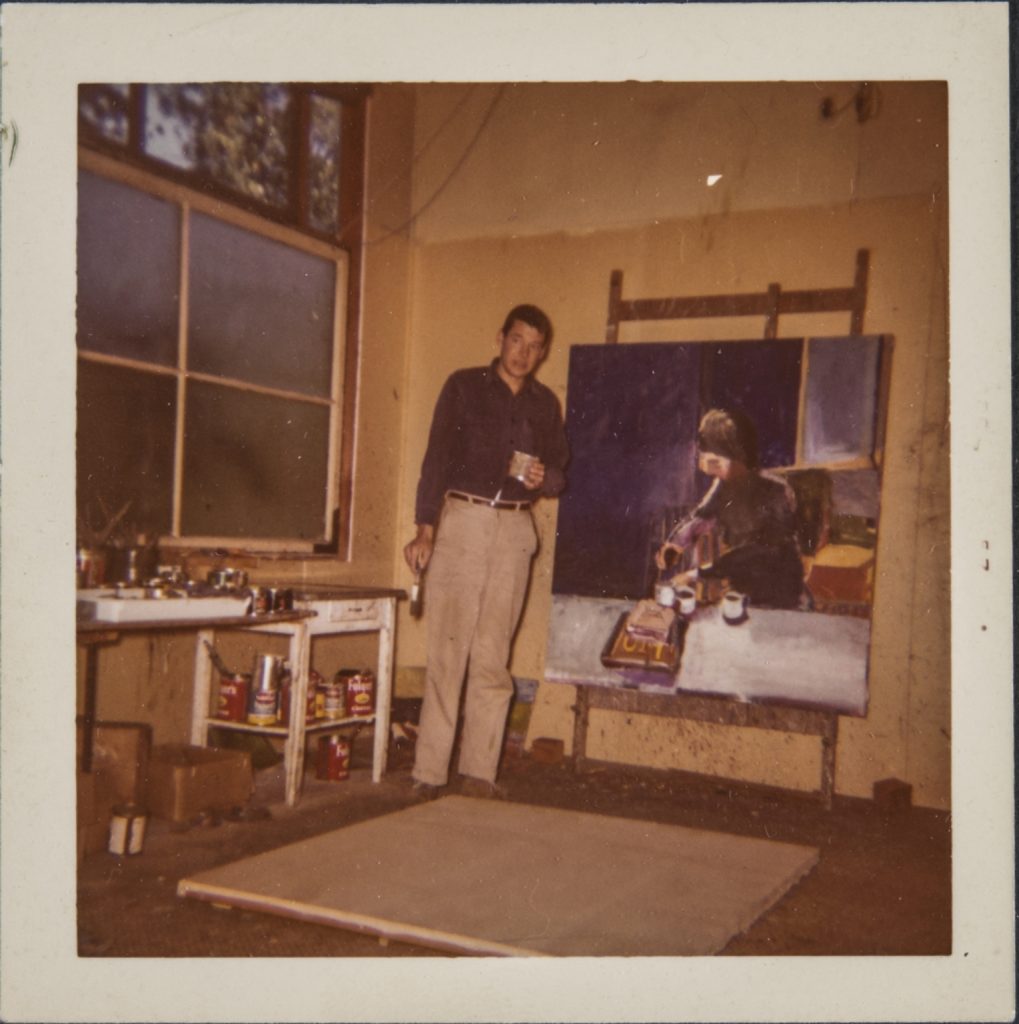

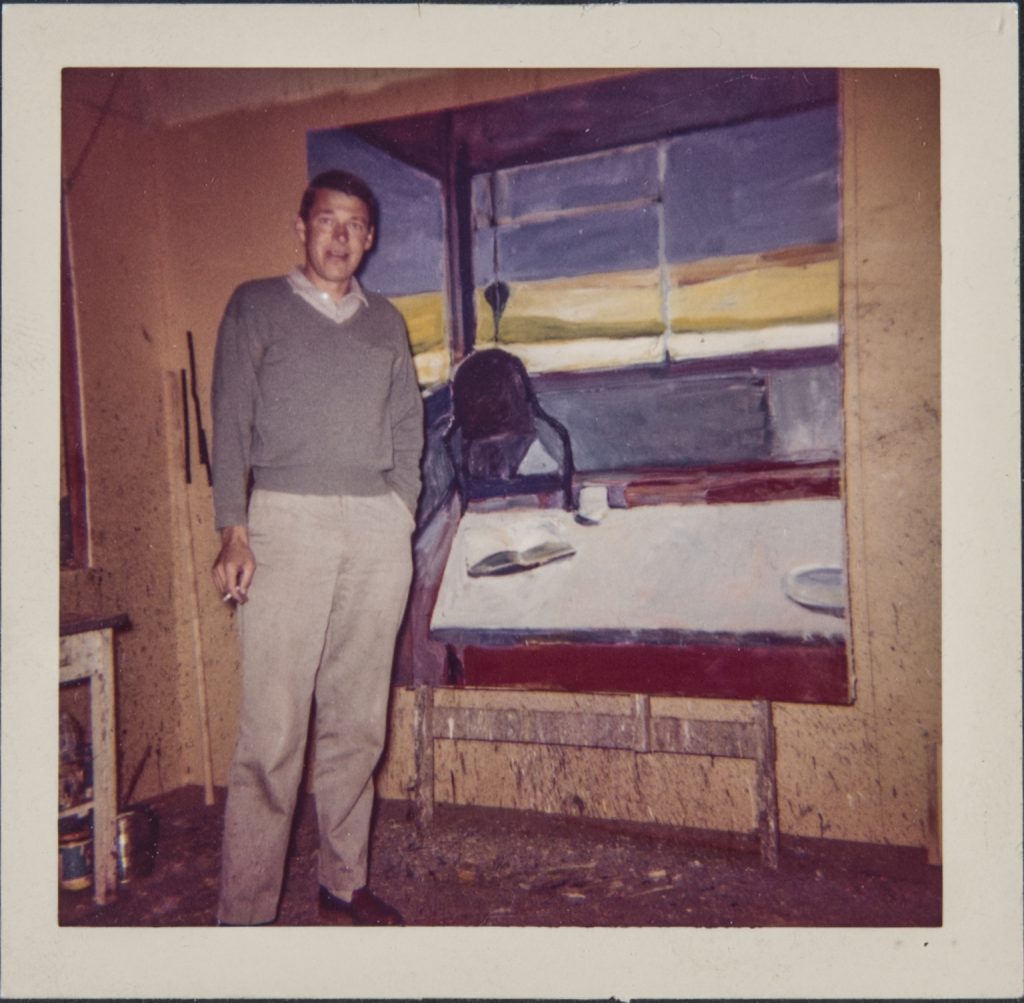

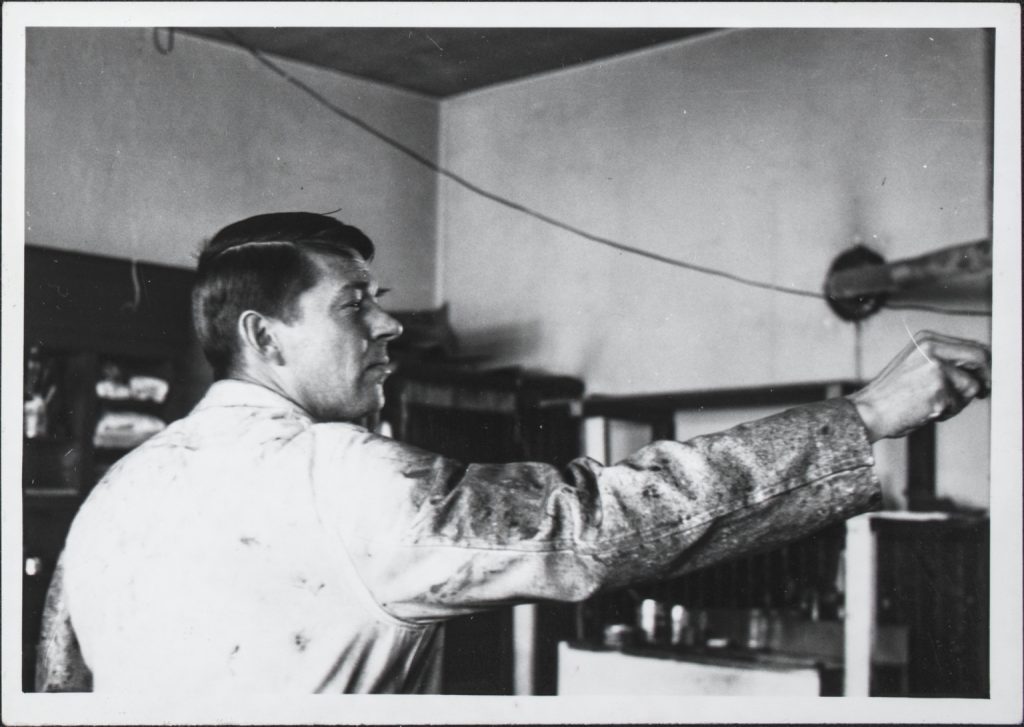

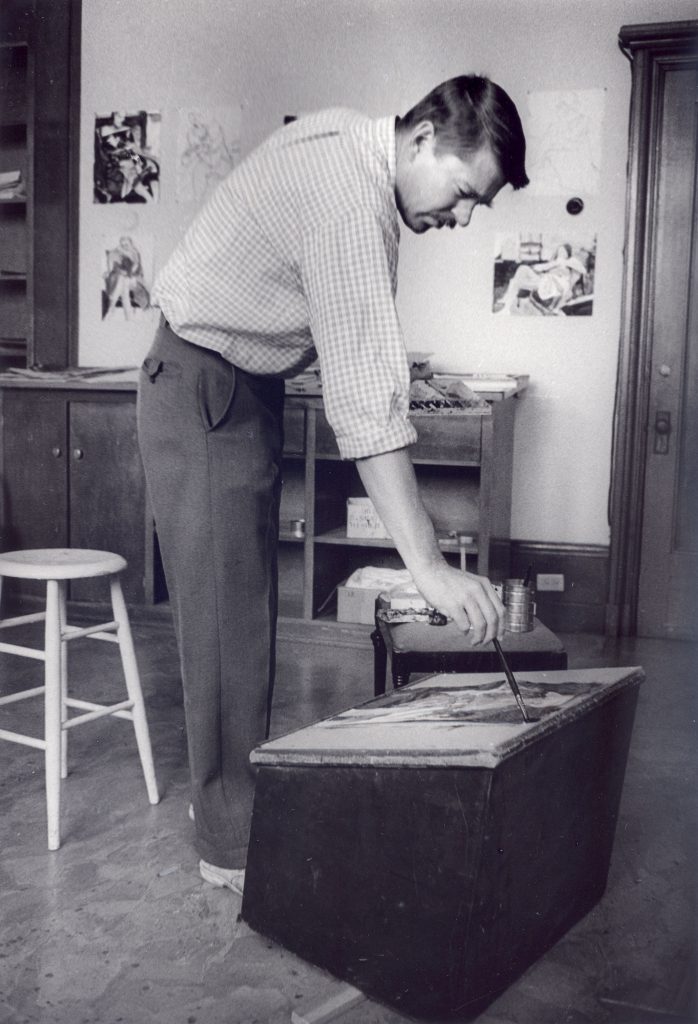

Art historian Herschel Chipp visits the studio with photographer Rose Mandel to work on a story for Art News. Mandel completes a rare series of portraits of Diebenkorn at work, some of which are reproduced in the published article.165 Diebenkorn says to Chipp,

The constraints on freedom in the painting of the figure are extreme, whereas with its environment the limitations are almost as few as with “pure painting.” It is the opposition and the interrelation of environment with its particular attitude and the figure with its distinct and concentrated psychology which concerns me at present. I find that this “person” I deal with creates a surrounding which in turn modifies, changes, sometimes even engulfs him. . . .

I am interested in those arrangements and configurations made by people when the look of what they produce is incidental to their intentions. For example, the trial card on which a house painter dabs colors in order to judge them, the farmer’s division of fields under cultivation as viewed from a vantage point, the cluster of hits on a target, the rapid sketch on a scrap of paper as a direction or description. These are all examples where chance seems a large factor in a look or a feeling but where intentions are involved. . . . The unforeseen consequences that occur, when they are in favor of the main idea of the painting, often seem to quicken my perceptions and produce insights and a deeper involvement. The most “real” look for me in painting is where one of the most interesting aspects of my own seeing is represented—the way things are endlessly out of place—sometimes delightfully, sometimes tragically.166

The article, one in a series called [X] Paints a Picture, will bring wide national recognition to Diebenkorn, despite the artist’s reservations.

Walter Chrysler visits Berkeley and buys five paintings directly from the artist, two abstract paintings and three figurative works. According to Phyllis,

[There were] headlines in the paper the next day, that local artists had been chosen by Chrysler. And Dick thought—in fact, he said to me, “What have I done wrong?” because he thought there must be something terribly the matter with his work if it was popular. And that was kind of how he felt about it. Even later. Always. He was suspicious of being successful.167

8–30 September: Richard Diebenkorn One Man Guest of Honor Exhibition at the Oakland Art Museum—an outcome of winning the gold medal at the Western Annual in November 1955—is the artist’s first showing of figurative paintings.

The figurative work receives a negative reaction from some. Phyllis will say,

I think everybody else makes more of it [the shift to figurative work] than he ever did. He never made that kind of distinction. He just kind of did it. He just decided to put people in and look out windows and stuff. To him, it was all of a piece, and to everybody else it was shocking. . . .

Paul Kantor was outraged. And one of Dick’s so-called collectors, Max Zurier—a nice guy actually—called him up and said “What have you done to my investment?!”168

September 1956–July 1958: Berkeley #42b (cat. 1479) and Berkeley #48 (cat. 1487) are included in Dorothy Miller’s Young American Painters, organized by MoMA; the exhibition tours colleges around the country.

October: Participates in Alain Jouffroy and K. A. Jelenski’s questionnaire for young painters, “Enquête sur la jeune peinture,” in the French magazine Preuves. To Jouffroy’s question, “In abstract painting, what appears more important to you: rhythms, the impact of colours, the interplay of spaces, or a certain kind of plastic exploration of the interior world—the graphic or the symbol?” Diebenkorn replies,

My answer to this question is best made by quoting my friend, the painter, Elmer Bischoff. “. . . it (the painting) may appear to us as a unique definition of a quality of feeling or, to use the stronger work, emotion. It may cut itself free of all surface connections and sink beyond reach. In this instance we may be as unaware of shape and color as we are unconscious, when reading, of type on a page. At this level what matters most to us is the power of a painting to pierce through all generalities to some particular poignancy of feeling.” 169

December: Flowers and Cigar Box (cat. 2070) wins the grand prize at the SFAA’s members show.

1957

Winter: Poindexter Gallery begins lending works to galleries and museums nationwide for both prospective sales and exhibition.

James Schevill interviews Diebenkorn, and writes a profile for Frontier magazine. Diebenkorn states, “Values come from the individual. I feel that a forceful quality in art truly representative of our modern situation will rise above the labels of abstraction and realism.” 170

Dore Ashton writes in her article “An Eastern View of the San Francisco School” for the Evergreen Review, “With the absence of Still . . . and the return, four years ago, to figurative painting by David Park, Elmer Bischoff, and several others, activity in San Francisco appears to be less inspired, less significant. Nevertheless, it is still, after New York, the major source of avant-garde painting of quality.”171

28 February–31 March: Seventy-Sixth Annual Painting and Sculpture Exhibition of the San Francisco Art Association at the SFMA; Diebenkorn is a prizewinner.

15 March–11 April: Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles opens with the exhibition Objects on the New Landscape Demanding of the Eye. Its director, Walter Hopps, selects Albuquerque #3 (cat. 1095). The show also includes works by John Altoon, Billy Al Bengston, Jay DeFeo, Roy de Forest, Ellsworth Kelly, Ed Kienholz, Craig Kauffman, Frank Lobdell, Ed Moses, Hassel Smith, and Clyfford Still.

9 April–4 May: Albuquerque #4 (cat. 1096) is on view in Modern Painting, Drawing and Sculpture: Collected by Louise and Joseph Pulitzer, Jr. at M. Knoedler and Co. in New York; the show will travel to the Fogg Art Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts, for the Summer. Aline Saarinen comments that Diebenkorn is “fashionable in sophisticated New York circles.”173

23 April–12 May: Woman by the Ocean (cat. 2080) and Seated Man (cat. 2087) are included in Painting and Sculpture Now at the SFMA.

May: Art News publishes “Diebenkorn Paints a Picture,” written by Herschel Chipp in 1956.

23 May: The painting Berkeley #54 (cat. 1490) is included in Fourth International Art Exhibition of Japan, appearing in four Japanese cities, including Tokyo, along with works by other distinguished American painters; the exhibition is organized by poet and curator Frank O’Hara with the International Program of MoMA, New York.

Summer: Teaches drawing at the University of Southern California (USC). Diebenkorn does not have a private studio, and produces his only works in ceramic. The family lives in a rental house on Alamitos Bay, south of Los Angeles. The Diebenkorns meet William and Shirley Brice at Vincent Price’s house, when Price invites the two couples and their children (the Brices’ son John is around the same age as Gretchen and Christopher) to use the pool at his home, suspecting that the two families will get along. His prediction proves correct; they quickly form a close and lasting bond. Phyllis says,

We have a couple of [ceramic] cups and several tiles that he made that Summer at USC. I’m not just sure why, but that’s where he did it. And he’d never done this before and never done it since. They’re . . . all black and white, and very worked.

Bill Brice was a professor at UCLA already and he was the son of Fanny Brice. Fanny Brice was most famous for her role as Baby Schnooks. . . . She was a very very famous radio and theater personality. She started in the follies and moved on from there—So, Billy was part of the movie world. . . . I don’t know how to explain we just . . . hit. . . . We also met Barbara Poe, because they took us to her house.174

18 June–1 September: The Green Huntsman (cat. 1163), Berkeley #22 (cat. 1346), Flowers and Cigar Box, and Woman by the Ocean (cat. 2080) are included in American Paintings, 1945–1957 at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

Fall: Teaches at Mills College in Oakland for one semester as a lecturer in the art department, substituting temporarily for Italian artist Afro Basaldella, known as Afro, until his arrival in California in December.175

8–29 September: Represented in Contemporary Bay Area Figurative Painting at the Oakland Art Museum, an exhibition curated by Paul Mills. The show also features Elmer Bischoff, Joseph Brooks, William T. Brown, Robert Downs, Bruce McGaw, David Park, Robert Qualters, Walter Snelgrove, Henry Villierme, James Weeks, and Paul Wonner. The show is the first to decisively present the figurative painters in the Bay Area as a group. Mills quotes Diebenkorn in the catalogue:

The initial oil studies now are like the paintings then [as a student at Stanford]. At that time I didn’t know how to go beyond. . . . [Now] I keep plastering it until it comes around to what I want, in terms of all I know and think about painting now, as well as in terms of the initial observation. One wants to see the artifice of the thing as well as the subject. Reality has to be digested, it has to be transmuted by paint. It has to be given a twist of some kind.176

Is uncomfortable with the show from the beginning, as Mills initially proposes an exhibition that groups the men and their works together in a manner that resembles a “School.”

10 September–13 October: Woman and Checkerboard (cat. 2081) wins the Women’s Board of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Award of Merit at the Second Pacific Coast Biennial Exhibition at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. Joseph Pulitzer Jr. and Andrew C. Ritchie are jurors. The painting is reproduced and mentioned in Arts Magazine.178 After Santa Barbara, the show will travel to the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco, the Seattle Art Museum, and the Portland Art Museum. Arthur Millier comments that the work “shows one of the leaders of the West Coast nonobjective painting now returning to figures and objects. But his ‘subject’ still is energy expressed in terms of space.”179

Figurative and abstract works are shown contemporaneously in various exhibitions.

1958

You can seldom invent a head—though if you could, it might be best of all. Usually I can’t believe in the head until I see it. I begin with a stage of getting a likeness of the particular person. This seems flat and I abandon it. I go to a second statement which is both more full around and more deeply involved with what the person is in essence. At this stage the painting could be a portrait but because it has missed I am not satisfied. But in going beyond this point I often lose touch with the person represented, at which point I abandon “portrait” restraints and become involved with some attitude I’ve found with this head—also with the painting itself. I find then that however objective my intentions were to begin with, I am now very much involved, myself, in the thing. The result of this may be a head that is satisfying to me. The remote possibility is that it remains a portrait and it is the portrait that is the most satisfying.180

24 February–29 March: Richard Diebenkorn: Recent Paintings at Poindexter Gallery, the artist’s second solo show in New York, presents only figurative paintings. The works are primarily paintings of solitary women near windows, still lifes of everyday objects, and the occasional landscape. Dore Ashton writes for Arts & Architecture,

Richard Diebenkorn’s recent flight into reality . . . has aroused considerable comment and probably caused him considerable embarrassment. The back-to-the-figure prophets have claimed him as their own and the abstract stalwarts have regarded him as a heretic beyond support. . . . No matter how much he tried to suggest the abstract grandeur of the vistas his personages contemplate, he could not endow these paintings with the horizonless flow of his former landscape abstractions. The people, as tenderly and even abstractly as they are observed, are insistent and hold the painter to their measure.181

Twenty of the twenty-six oil paintings sell within the first three days. Poindexter keeps Diebenkorn apprised of the show’s success through letters, writing,

It was wonderful for us to have the kind of enthusiasm and wish to own that this show has created. Of course, there are dissenters who don’t like this kind of painting, but even they pick out a particular aspect to admire.

The attendance has been splendid and people stay a long time and want to talk to us about your painting. . . . The “Time” people were in yesterday. We didn’t tell them anything but “facts.” “Arts Magazine” has a reproduction and a good review.

Sales are still developing. Besides the ten that I mentioned in my first letter, there are two more definite, making five large and seven small canvases altogether . . . People are telling other people to come in, and we are getting a good many we have never seen before—all in all a very lively experience.182

Diebenkorn responds,

I’m stunned by the number of purchases. I’m refraining from any interpretation of this phenomenon. I hope that most of them are definite since I felt, on receiving the news, morally obliged to withdraw my Guggenheim application—which I did.

I have no more work to send back to you. . . . My studio becomes a pretty uncomfortable place when it is cleaned out and although I continue to scrape and repaint day by day I’m not coming thru with anything that is what I want. I think I’ll have to disappoint you too, where sending work back when I get it is concerned. It would be an impossible burden to put on my painting process to have to think during the year “is this a good enough one to send back to N. Y.” I can’t as a matter of fact think this way at all—rather I have to keep it around until one day it doesn’t look so good and then I repaint it. When a group of these survive the months—or year or so—then I hope that you will want to show them. Really I hate to disappoint.183

Spring: Last semester teaching at CCAC; decides to focus entirely on painting.

I took a year off, after the Ellie show, I guess it was in 1958, because I had done very well and I thought maybe I just didn’t have to teach at all then—and I didn’t, at that point. But I had at this time a studio at home in my backyard. And there was never any reason to leave the premises, you know, and this became suddenly lonely not teaching—or not doing something, not having some reason to go to San Francisco, or go anywhere. And I could just remember one morning looking out the window and watching these men on their way to the bus with their newspapers under their arms and envying them.184

Spending the majority of his time between his house and the backyard, moves to a new studio in the so-called Triangle Building at 851 Sixty-First Street, on the Oakland-Berkeley border. His studio, located behind a working-class bar called the Triangle, features a red-checkered floor and bead-board wainscoting.

Another thing that really affected me was a studio I had in Berkeley. It was a triangular room at the back of a tavern; I could open a door and look right down the bar at all of the regulars. There was a lot of rather useless furniture built into the wall, and when I pulled it off you could see many different overlapping layers of house paint. The effect was fascinating.185

April 1958–January 1959: Berkeley #24 (cat. 1347), Berkeley #58 (cat. 1493), and Girl on a Terrace (cat. 2079) are included in Seventeen Contemporary American Painters, organized by the American Federation of Arts for the American Pavilion at the Brussels World Fair. The exhibition travels to the U.S. Embassy in London. British critic Lawrence Alloway says, “Though his subjects are unmistakably American (for example, long torsoed men with trousers resting low on the hips, which is as American as Hopper) his subjects are, more than Hopper allowed, parts of the painting.”186 This is the first showing of Diebenkorn’s work in London.

Prominent collector Richard Brown Baker purchases Girl with Cups (cat. 2175) from Poindexter Gallery.187

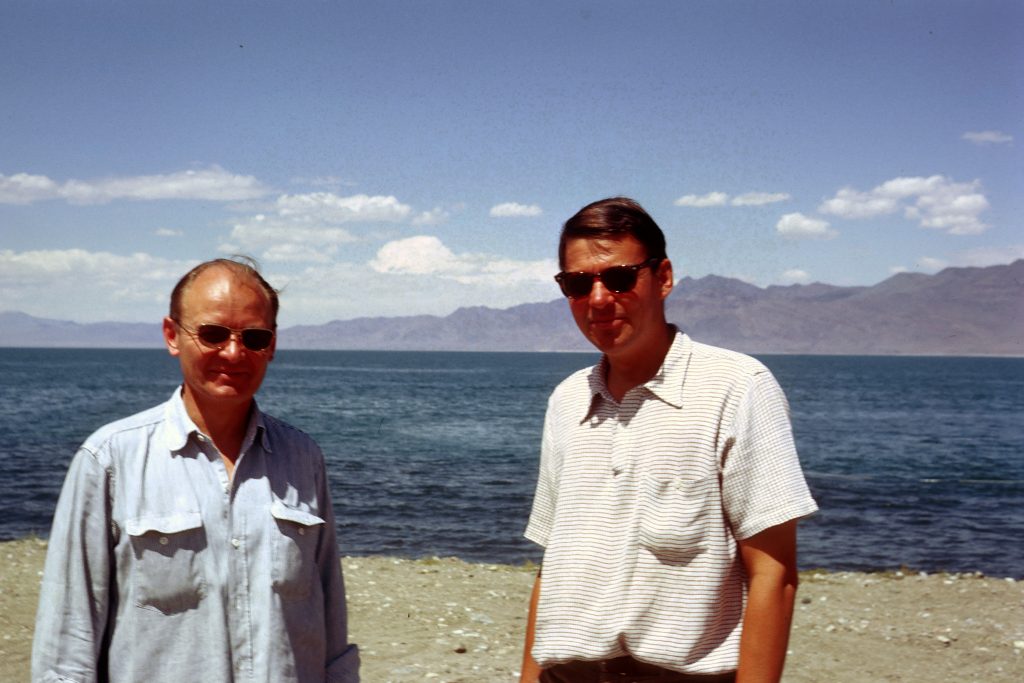

28 September: Travels for the first time to Santa Cruz Island, one of the Channel Islands off the coast of Santa Barbara. The family of Diebenkorn’s Stanford friend Carey Stanton purchased nine-tenths of the island in 1937, and Stanton moved there permanently in 1957, leaving behind his medical practice in Southern California to run his family’s cattle business. Diebenkorn spends two weeks on the island before Phyllis joins him for an additional week.

Santa Cruz Island will play a significant role in Diebenkorn’s life; he will travel to “Carey’s Island” almost once a year, or more, for the next thirty years. Phyllis frequently joins him, and the entire family travels together to the island for the occasional holiday or birthday; the trips sometimes turn into reunions for their group of college friends. Stanton keeps a detailed guest book during the course of his time living and working on Santa Cruz Island.188 Throughout his numerous visits over the years, Diebenkorn paints and draws the island’s surroundings. He also designs the flag for the island, organizing the composition according to the golden section. Stanton becomes an avid collector of Diebenkorn’s work—beginning with Palo Alto Circle (cat. 99) in 1962—either purchasing or receiving from the artist many of the works completed on the island; Stanton will never sell these works, which now reside at the Santa Cruz Island Foundation in Carpinteria, California.

16 December 1958–10 January 1959: Ferus Gallery moves across the street from its previous location in Los Angeles and reopens as the “New” Ferus. Diebenkorn’s work is selected for the inaugural exhibition. Irving Blum, then director of the gallery, on Diebenkorn:

Well, Diebenkorn was most important to the Ferus group as somebody to emulate or as somebody to react against. Either way, he was a powerful figure. There were very few artists as old as Diebenkorn, as committed and as solid as Diebenkorn was during those years in this region. So Diebenkorn was always a beacon for younger artists and, as I say, for either reason: as somebody to get beyond or somebody to emulate, and it went both ways. Diebenkorn always had a strong—exhibited a strong kind of moral position, and that position had, I think, a profound influence on younger artists within his orbit.189

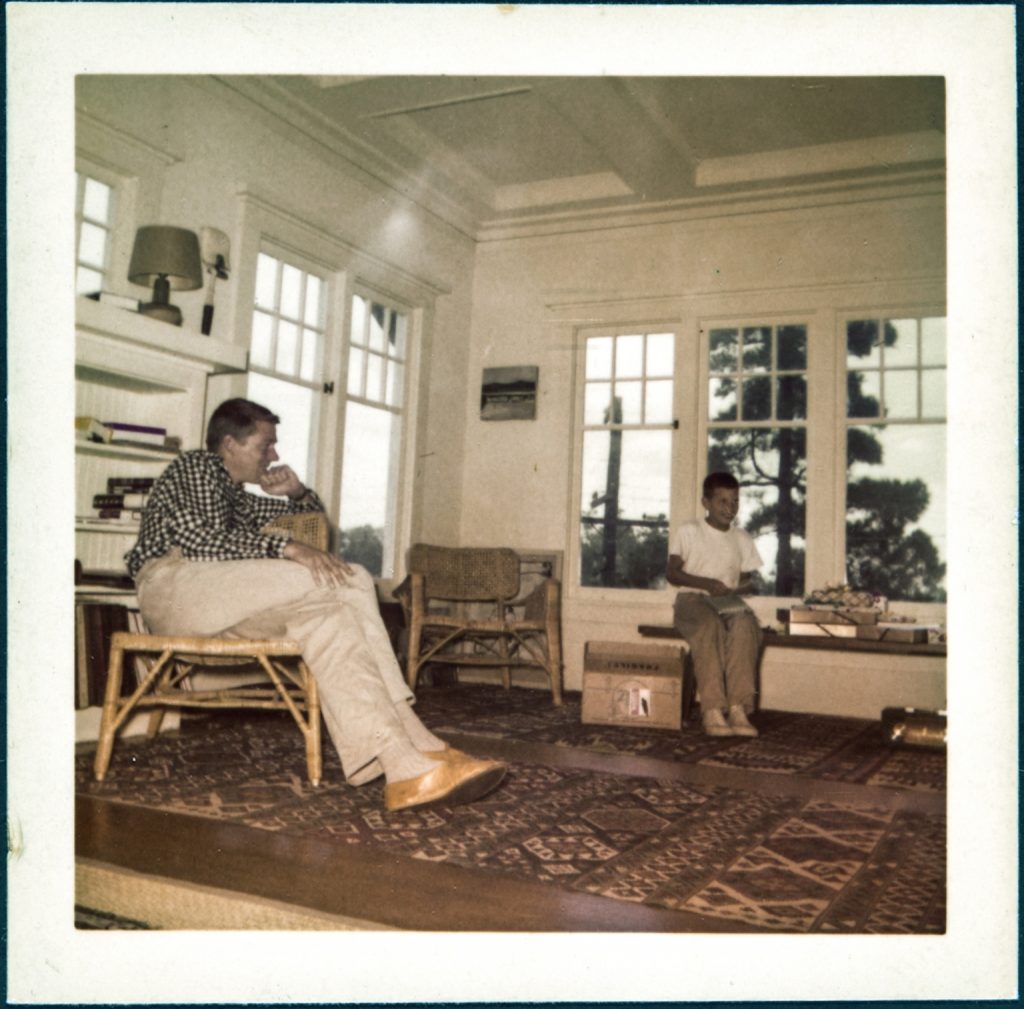

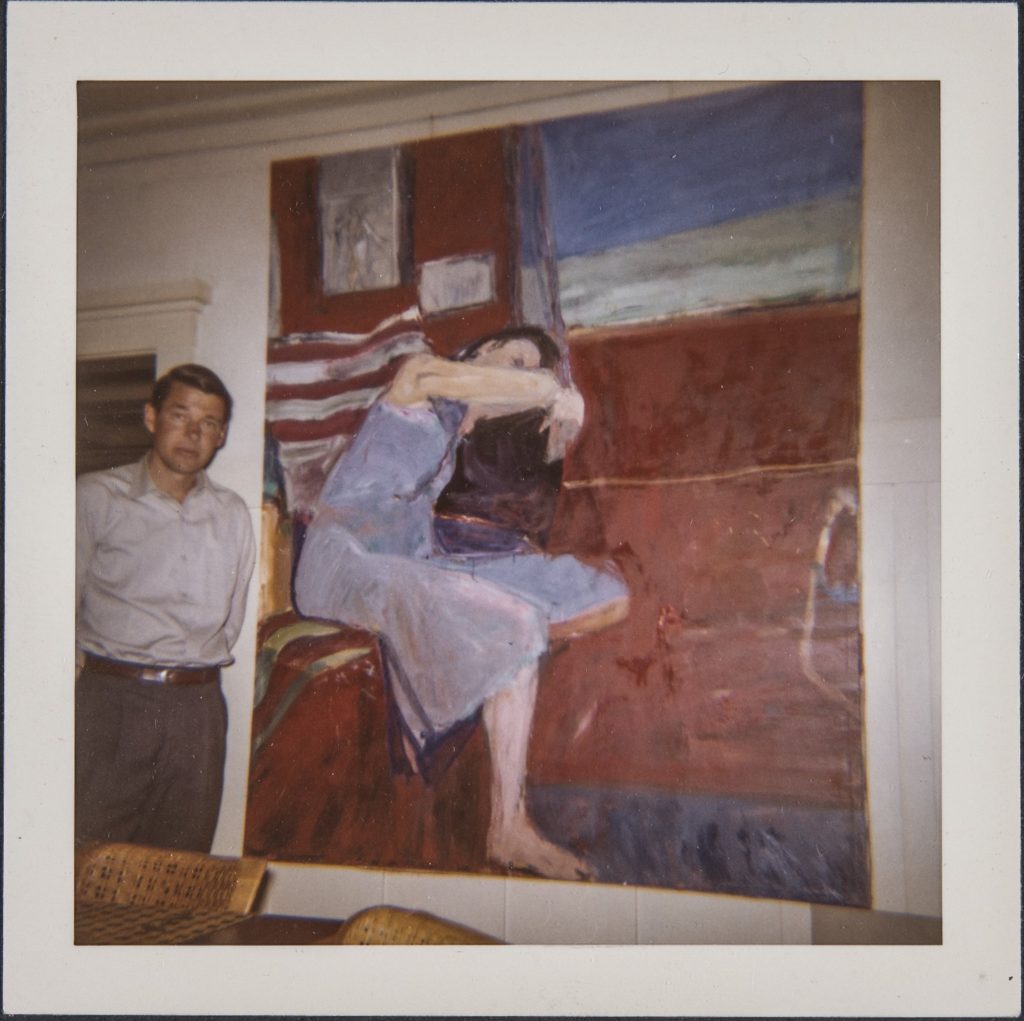

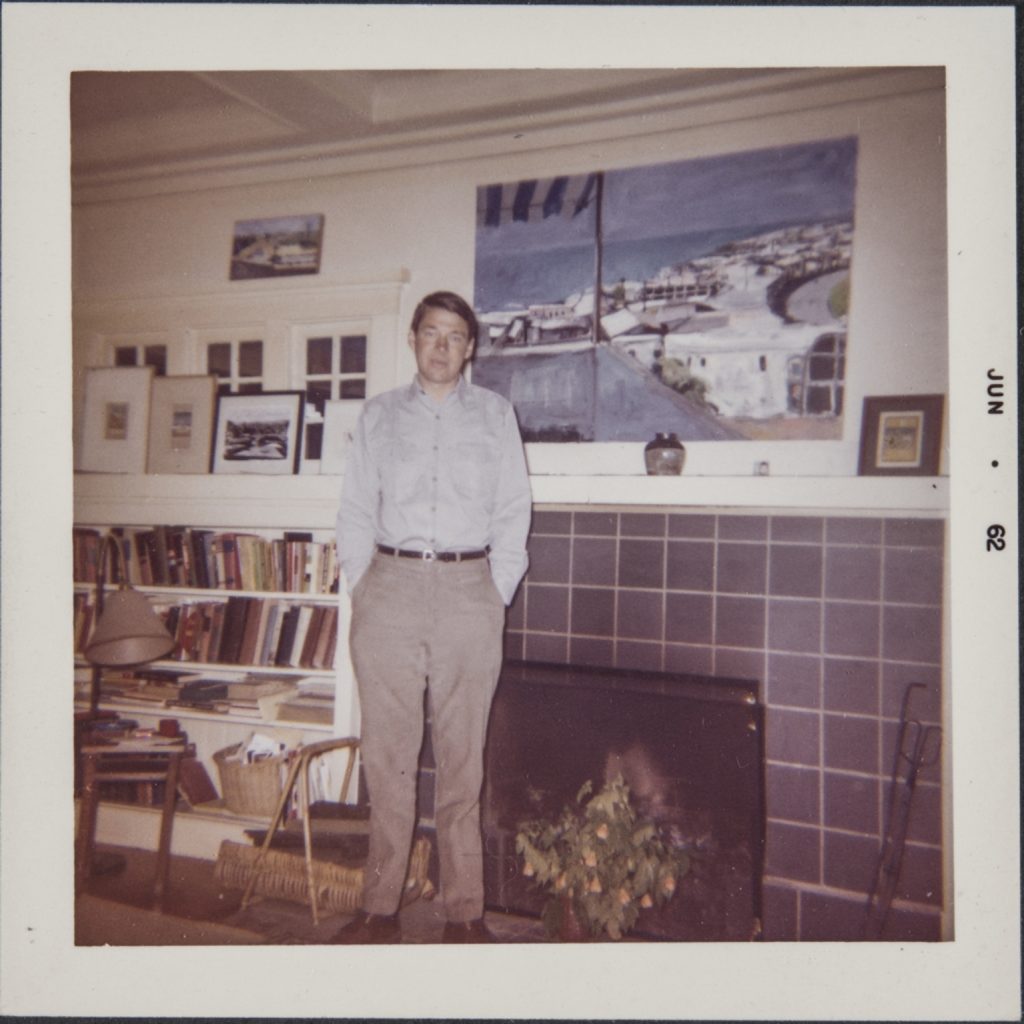

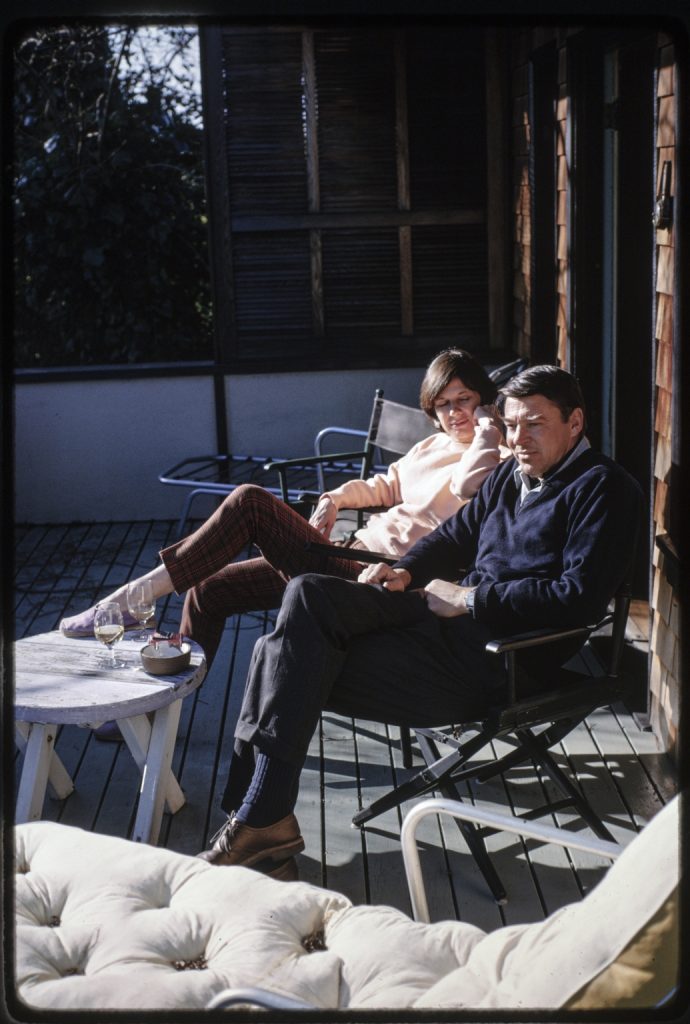

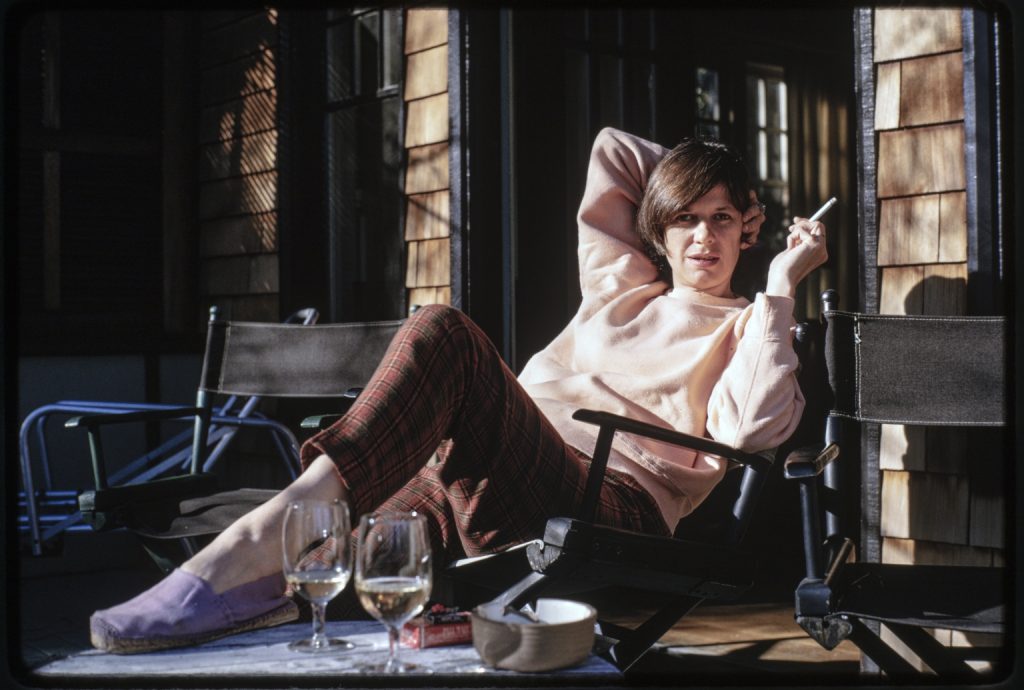

Hans Namuth photographs Diebenkorn. The session takes place in the artist’s studio, around the neighborhood in the Berkeley hills, and in his home with Phyllis and friends Richard and Joan McDonough.

In a profile by William Steif, Diebenkorn states:

I’ve tried to verbalize why I paint . . . the way I do. It’s very hard. I even set out to write it all down. I wrote one reason, a second, then went back and corrected the first so it wouldn’t contradict the second. But in painting, it doesn’t matter if you contradict.190

1959

2 April–3 May: Girl and Striped Chair (cat. 2533) wins San Francisco Art Association Cash Award for $500 at the Seventy-Eighth Annual Painting and Sculpture Exhibition of the San Francisco Art Association at the SFMA. Alfred Frankenstein notes that this is the first annual at which figurative work dominates.191

Summer: Teaches at the University of Colorado, Boulder, as a visiting professor; friend and colleague Don Weygandt, a professor there, helps him secure the position. Lives at 842 Grant Street; uses a spare bedroom as a studio. The Weygandts and the Diebenkorns spend much of their Summer together. Phyllis remembers,

We’d take the kids and drive up into these gorgeous mountains around Boulder and have wonderful picnics. What we used to do a lot was do the I-Ching. That was fun and interesting. That was that Summer . . . it was because we needed the money. He’d been teaching at CCAC and was getting more in demand.192

Fall: Returns to teach painting and advanced painting at CSFA; he will continue to work at the school in some capacity until the Spring of 1966. The school, then under the directorship of Gurdon Woods, is soon to become the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI).

30 September–29 November: Peter Selz curates New Images of Man at MoMA in New York, exhibiting four large paintings of Diebenkorn’s: Girl on a Terrace (cat. 2079), Girl with Cups (cat. 2175), Man and Woman in a Large Room (cat. 2184), and Man and Woman Seated (cat. 2539). Selz selects Diebenkorn and Oliveira as the Bay Area representatives, feeling that their work is the strongest and the least “anecdotal”; according to Selz, “In the east the critics weren’t interested in the figure or the American Hinterlands.”193 Jerrold Lanes reviews the exhibition in Arts Magazine and names Diebenkorn “the best not-yet fashionable artist.”194

Writes in a note to Selz, “My ideal . . . was to present a vision of the world simply in terms of the acts, problems and realizations of painting.”195

Artist Charles Cajori, while teaching at UC Berkeley for the year, occasionally joins the drawing sessions.196

1960

Winter: David Park is diagnosed with terminal cancer at age forty-nine. Diebenkorn spends much of the year caring for his friend and mentor; by the end of Park’s illness, he is the only person outside the family allowed to enter the house unannounced.197

Spring: Sits on the jury for the Art Institute of Chicago’s 63rd Annual Exhibition by Artists of Chicago and Vicinity. The Diebenkorns go to New York to visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Frick Collection, and to Merion, Pennsylvania, for the Barnes Foundation. It is Diebenkorn’s first visit to all three museums.198

1 June: Juries the Los Angeles County Museum’s Annual Exposition of Artists of Los Angeles and Vicinity with Clement Greenberg and Henry Francis.

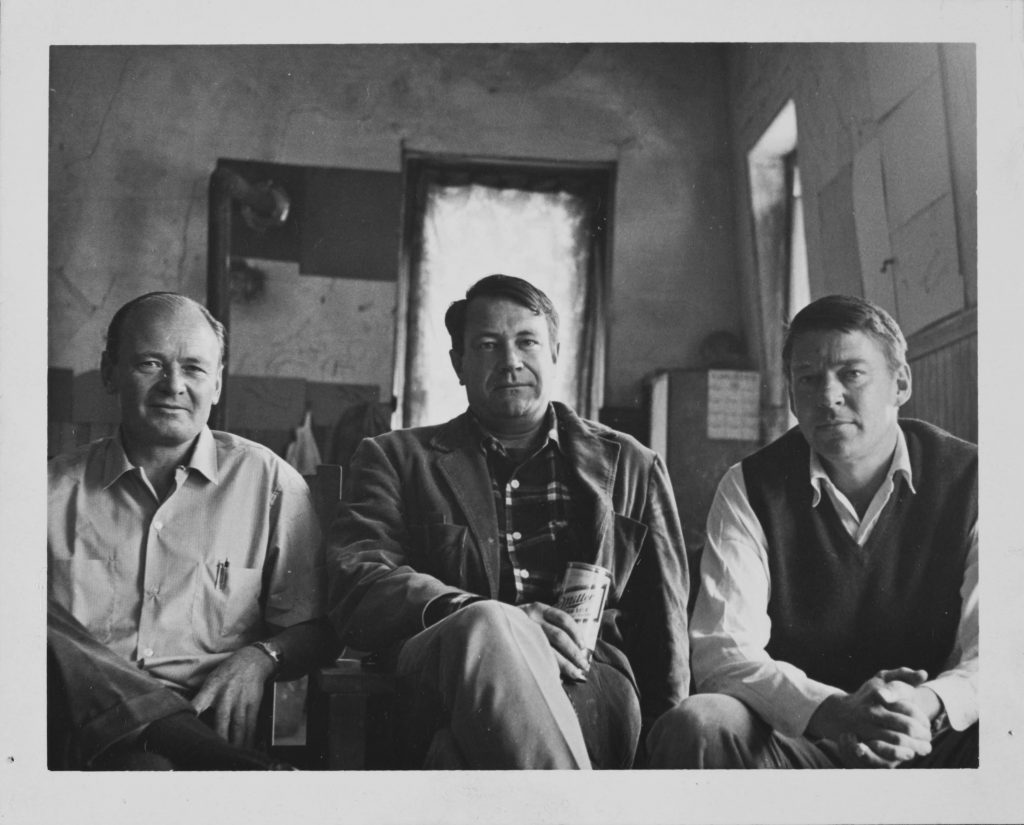

July: Eleanor C. Munro’s article “Figures to the Fore,” published in Horizon magazine, is entirely devoted to the works of Diebenkorn, Park, and Bischoff.199

6 September–6 October: A mid-career retrospective, Richard Diebenkorn, organized by Thomas W. Leavitt, opens at the Pasadena Art Museum. A version of the exhibition, Recent Paintings by Richard Diebenkorn, opens at the Legion of Honor from 22 October to 27 November.

20 September: David Park dies. Park’s wife, Lydia, asks Diebenkorn, Bischoff, and gallery owner George Staempfli to help her perform an inventory of the artist’s work the day after his death.

After Park’s death, Lobdell joins the weekly drawing group. Lobdell and his then wife Ann Morency spend time with the Diebenkorns, often having dinner together at the Diebenkorns’ house in Berkeley. After dinner the two men sometimes draw late into the night.200

8–26 November: Elmer Bischoff, Richard Diebenkorn, David Park opens at Staempfli Gallery in New York. The show is a tribute to Park and the friendship between the three artists. John Canaday reviews the show in the New York Times:

The Californians at Staempfli’s (Elmer Bischoff, Richard Diebenkorn and David Park) have rejected the unhappy position that this darkness is beyond help, that the pure esthetics of abstract painting must henceforth substitute for the emotional conviction of a positive response to the world. All three of these men have passed through the experience of abstraction, have found it—for them—an impasse, and are finding their way out by a return to figure painting.201

Willem de Kooning visits the Bay Area and works on lithographs with Nathan Oliveira and George Miyasaki. The Diebenkorns host a dinner for him at their Berkeley home.202

1961

When asked about the apparent return to the figure as a new direction for contemporary art, Diebenkorn replies,

What interests me is that a few strong painters are at work, some of whom, incidentally, will remain “non-representative” while others will “return.” Others yet will not have to return, having never departed. “Out-moded” will mean as little to them as it meant to Monet.203

13 March–8 April: Third solo show opens at Poindexter Gallery; the exhibition includes twenty-three figurative paintings. Reviews are written by Irving Sandler (in Art International ), Valerie Peterson (Art News), and Stuart Preston (New York Times). In a review in Arts Magazine, Sidney Tillim discusses Diebenkorn in terms of the “new Realism,” placing him alongside Alex Katz and Philip Pearlstein:

[Diebenkorn] is closing in on the figure and trying to locate it in its own space. The new Realism pivots on the crucial admission that an object is only as credible as its environment and that the environment is only as credible as the artist’s commitment to the object. In this respect Diebenkorn’s new paintings reveal all the uncertainty that he has been able to submerge in design since he turned from Abstract Expressionism, officially, about four years ago.204

19 May–26 June: Richard Diebenkorn at the Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

Spring: Phyllis completes her coursework and passes her orals for a PhD in psychology at UC Berkeley.

Summer: Teaches at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) as a visiting instructor. The Diebenkorns spend time with the Brices and Barbara Poe; Diebenkorn meets Fred Wight, head of the art department at UCLA. Wight begins a personal campaign to bring Diebenkorn to Los Angeles to teach as a full-time professor.

July: Spends two weeks working as a guest artist at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles.

27 October 1961–7 January 1962: One of seven artists to have concurrent one-man shows in the Carnegie Institute’s 1961 Pittsburgh International Exhibition of Contemporary Painting and Sculpture. Diebenkorn’s abstract and figurative paintings are shown together.

23 November: The family travels to Santa Cruz Island for Thanksgiving. A newly built airstrip makes the island accessible by plane.

5 December 1961–17 January 1962: Drawings by Richard Diebenkorn and Frank Lobdell, organized by Walter Hopps, is shown at the Pasadena Art Museum.

The Whitney Museum of American Art purchases Girl Looking at Landscape (cat. 2178).

1962

Begins painting cityscapes.

March: The National Institute of Arts and Letters in New York awards Diebenkorn a grant for $2,000; two of his paintings are included in An Exhibition of Contemporary Paintings and Sculpture at the American Academy Gallery in New York. The ceremony for the grant is in May.205

24 April–15 May: Returns to Tamarind to complete a set of lithographs made during the previous Summer’s informal fellowship. The Tamarind Fellowships generally last for two months, but Diebenkorn is unwilling to take that much time away from his paintings. Later writes that his “most undistinguished work has been stone to Arches [paper] and I don’t enjoy much of the process which has remarkably little parallel to my work with canvas or paper.” 206

October: Clement Greenberg’s “After Abstract Expressionism” is published in Art International.

Featured in Artforum’s Four Drawings series.

4 November–9 December: The Gifford and Joann Phillips Collection is shown at the Art Galleries, UCLA. A symposium is held at UCLA, with Diebenkorn, Lee Mullican, and Emerson Woeffler, and moderated by Fred Wight. Artforum later publishes excerpts in the April 1963 issue. Wight asks Diebenkorn what it is that makes a painting “gel or make sense”:

[It’s] different for every painting. This is an extremely mysterious thing to me. The painting may be all wrong to me at one moment, and then perhaps some slight alteration can throw the stance of the thing in a different way so that perhaps it can be almost right, or miraculously right to me. I find this a curious thing, this mystery, and with people who are students of painting who I talk to a bit, since I am supposed to be a teacher, the same thing happens. I see it happening. It’s kind of marvelous.208

Late 1962: Begins working on intaglio prints with Kathan Brown at her workshop, Crown Point Press; the studio is less than a year old at the time, and still at its first home in Richmond, Calif. Brown writes,

One afternoon in late 1962 Richard Diebenkorn telephoned me. He dislikes the telephone and was always reticent with people who were not close friends. More than thirty years later, I marvel that he called. But fortunately for me, he did.

He had heard I had a printmaking workshop. On a guest teaching stint in Los Angeles, he had been introduced to drypoint by a graduate student. He liked using it as “a way of drawing,” he said. After returning to Berkeley, he wanted to do more drypoints but needed a place to print them. . . .

I invited Diebenkorn to a regular Thursday evening drawing group where a live model posed and a group of artists drew directly on plates. He came several times. But much as he liked drawing on a plate, he didn’t like printing it, and soon he began to bring plates to afternoon workshop sessions so I could print for him. After I moved the press to Berkeley, he continued to work whenever he wanted printmaking to give him, as he later said, “a refreshing change of pace in my work as a whole which in turn may provide new perspectives on it.”209

1963

Winter: Phyllis teaches introductory psychology courses at San Francisco State College, filling in for a professor on sabbatical.

March: In an article on realism, published in the Hudson Review, Hilton Kramer speaks of the “New Realism” and Diebenkorn at length.

April: Sits on a jury for an exhibition at the California Medical Facility, a prison in Vacaville, Calif., where he taught art classes. Wayne Thiebaud is also on the jury.210

27 April–2 June: Drawings by Elmer Bischoff, Richard Diebenkorn, and Frank Lobdell at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, organized by the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts.

Fall: Is appointed the first artist-in-residence at Stanford University, with the help of Daniel Mendelowitz.212 Temporarily moves to Palo Alto. Diebenkorn’s studio is in the renovated quarters in the old Union. Although his contract does not require him to teach a class, he opens his studio a few times a week for students to drop in and visit.

Diebenkorn, Phyllis, and Christopher live at 1241 Harker Street, Palo Alto; Gretchen enters her freshman year at Stanford, and Christopher attends Palo Alto High School. They befriend Tom Hitchcock, a physics professor, and his wife Bebe, later known as Flora; the four bike around Palo Alto in the evenings and call themselves the Fireflies. Meets Al Elsen, art history professor, and Lorenz Eitner, head of the art department and director of the school’s museum. Diebenkorn continues to visit San Francisco each week for the drawing sessions with Bischoff and Lobdell; due to the interruptions caused by his open studio hours, he paints very little while at Stanford.

Photographer Leo Holub, then working for the Stanford University Planning Office, visits Diebenkorn’s studio, and takes his first pictures of the artist. Holub will go on to found the university’s first photography program in 1969. These informal photography sessions will continue until the last year of Diebenkorn’s life.

7 September–13 October: Richard Diebenkorn: Paintings, 1961–1963, organized by Ninfa Valvo, is presented by the de Young Museum.

29 October–16 November: Richard Diebenkorn opens at the Poindexter Gallery. The show includes seventy-three works, forty-one of them paintings. Poindexter notes to Diebenkorn that many artists, including Mark Rothko, Stephen Pace, and Helen Frankenthaler, attend the opening.214 Valerie Peterson writes for Art News, relating Diebenkorn’s work to Matisse’s 1910–15 period.215

Continues to work on zinc plates at home and in the studio, drawing scenes of his daily life: a hair-cut, a conversation, Phyllis reading, glasses on a table; Kathan Brown prints the plates at her press in Richmond.

1964

Spring: Second semester as artist-in-residence at Stanford. The artist continues to focus on drawing and intaglio works with Crown Point Press. Phyllis, after months of pain due to a slipped disk, undergoes successful spinal surgery.

3–26 April: A show of figure drawings from 1960 to 1964 opens at the Stanford University Art Gallery. Diebenkorn works with graphic designer Ann Rosener on the catalogue, which is not published until 1965. While Rosener ultimately disagrees with the handling of the reproductions in the catalogue and takes her name off the project, she and the Diebenkorns become lifelong friends. Diebenkorn designs the cover himself, writing of the catalogue, “I like the cover . . . which I designed— nothing exciting—just quiet and kind of right.”218

After this show and the publication, Diebenkorn’s figure drawings are in high demand and appear in numerous shows across the country in various groupings.

April: Father is diagnosed with terminal cancer.

17 April–17 may: Wins the Emilie Sievert Weinberg Award for Cityscape #4 (cat. 3372) at the EightyThird Annual Exhibition of the San Francisco Art Institute. All four cityscapes are shown at the SFMA.

June: Father dies in La Jolla. Stays at his parents’ home for the month to help his mother. Phyllis moves the family out of the house on Harker Street and back to Berkeley.

Focuses primarily on works on paper, producing dark and dense still lifes.

Fall: Travels to the Soviet Union as a representative of the United States with the Department of State’s Cultural Exchange Program. The Department of State runs the program ostensibly to share Western culture with the Soviet Union, using art to build bridges between the strained nations.219 Phyllis believes Diebenkorn was selected because of his well-vetted record and his success as a figurative painter.220

Phyllis and Diebenkorn fly to Paris, where they spend a few weeks while they wait for their visas; it is their first time in Europe, and they spend their days immersing themselves in the city’s museums, especially the Louvre, and visiting Chartres.

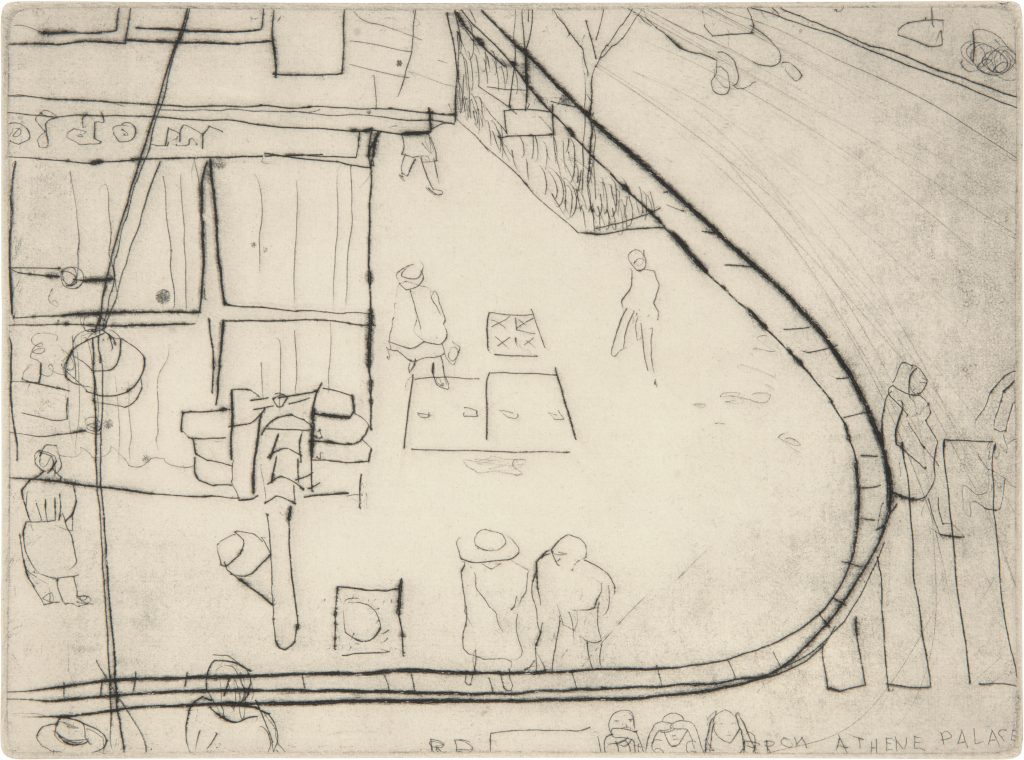

Once they receive their visas, the couple travels to Moscow. Deputy director of Soviet affairs William Luers and his then wife, Jane, accompany them; Luers will remain friends with the couple. From Moscow they visit Suzdal in Vladimir, and St. Petersburg (then Leningrad); from St. Petersburg they fly south to Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Diebenkorn insists on going to Samarkand, but the Soviet guides are reluctant; he agrees to skip a planned trip to Kiev in order to visit the historic city and its architecture. From Uzbekistan they visit Tbilisi, Georgia, and Baku, Azerbaijan. After their return to Moscow, they travel to Bucharest, Romania; to Yugoslavia, where they drive up the coast of the Adriatic from Belgrade to Split; and finally to Munich.221 During their trip they meet with numerous artists as an act of cultural diplomacy.

The Diebenkorns visit the restricted art collections at the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, and the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow, seeing works by Matisse, Cézanne, Renoir, Gauguin, Malevich, and others. They see the Matisse paintings The Dance (1910), Music (1910), The Painter’s Family (1911), Conversation (1908–12; see Nash essay, fig. 66), Red Room (Harmony in Red) (1908; see Elderfield essay, fig. 78), The Moorish Cafe (1913), and the artist’s Moroccan Triptych: Landscape Viewed from a Window, Tangier (1913), Zorah on the Terrace (1912– 13; see Elderfield essay, fig. 96), and The Casbah Gate (1913).222

Phyllis recounts,

Part of what our state department had arranged was that we could go upstairs and see the hidden things so we went to a floor that no Soviet except the people that worked at the museum ever had access to and the whole museum was filled with things, figurative stuff, mostly by the Russians. And then we got up there and there were things by the Russian avant-garde from [teens] and then there were all these gorgeous Matisses and beautiful Renoirs and Gauguins . . . all hidden away. . . .

And a lot of it we’d never even seen reproductions of . . . because the two guys in Russia who collected—Shchukin and Morozov, collected primarily Matisse, but probably had something to do with the Gauguins and other stuff. They did this primarily around 1910–11 so they’d never been available for long. They were confiscated by the Soviets from these private homes, where the only people who could see them were their guests. Anyway, Dick was really thrilled. They’ve since been here, and everybody knows which ones they are, but at the time we didn’t even know what was there.223

In Romania, they visit Constantin Brancusi’s studio and museum. In Bucharest they spend one night unaccompanied by their Soviet guides, and are invited to a local artists’ party. During their visit, Diebenkorn works on four drypoint plates, which are prepared and printed by American printmaker John Ross.224

The couple suspect they are being spied on throughout their trip. While in Yerevan, which overlooks Mount Ararat, they are separated from William Luers. As Phyllis later recounts, “We spent that night in our room, writing notes to each other and burning them in the ashtray. Looking back on it it’s like a bad movie, but we were sufficiently terrified, we didn’t know what else to do.”225

The Diebenkorns end their official trip in Germany. On their way home they stop in England to stay with Lydia Park, David Park’s widow, and her new husband, Roy Moore.

Their stay in the Soviet Union, and especially the encounter with the Matisse paintings, which few Westerners had seen, comes at a critical moment in Diebenkorn’s work:

At about this time, the representational thing, the figure thing, was kind of running its course. It was getting tougher and tougher, and at about the time of the trip—maybe it started before, or maybe it was right afterward—things really started to flatten out, in the representational. Five years earlier I was dealing with much more traditional depth, space. . . .

I’m relating this to Matisse, because of course the Matisse painting was much flatter in its conception than my representational painting.226

29 September–24 October: While in the Soviet Union, Diebenkorn’s first international solo show opens at the Waddington Galleries in London.

6 November–31 December: Gerald Nordland organizes a retrospective exhibition at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art in Washington, D.C., which travels to the Jewish Museum in New York and to the Pavilion Gallery in Newport Beach, Calif. Diebenkorn sees the show while in Washington, D.C., for his debriefing with the U.S. Department of State before returning to California from Europe and the Soviet Union. The artist was highly involved in the catalogue text for the exhibition.

22 December 1964–3 January 1965: Donates a lithograph to 100 Artists for Free Speech, along with Frank Lobdell, Hassel Smith, Elmer Bischoff, John Hultberg, and Peter Voulkos, among others. The exhibition and sale are at Berkeley Gallery in support of the Faculty-Student Legal Defense Fund of UC Berkeley.

Only one painting is dated 1964, Untitled (Seated Woman with Hand to Mouth) (cat. 3521).

1965

Paints Recollections of a Visit to Leningrad (cat. 3642), displaying the effect left on him by the Matisse works he saw in Russia.227

The Triangle Building is condemned to make way for the construction of the Bay Area Rapid Transit (commuter rail). The loss of his beloved studio saddens Diebenkorn, and he returns to work in the studio he built behind the Hillcrest house.

Fall: Christopher enrolls at UC Berkeley. Diebenkorn teaches at SFAI.

1–31 October: Recent Drawings by Richard Diebenkorn opens at Paul Kantor Gallery, Beverly Hills.

December: Crown Point Press publishes the portfolio 41 Etchings Drypoints in an edition of twenty-five. It includes forty-one of the intaglio prints that

Diebenkorn produced with Kathan Brown between 1962 and 1965. Brown recalls,

When I mentioned the book idea to him he was mildly interested mostly because he hadn’t printed editions of any of his drypoints and this might be a good way to get them out.

But as time went on he became more and more involved with the book. For the sake of variety in the book he learned other methods of printmaking—soft ground, etching, aquatint. The book became a kind of diary, into which he poured his introspections (visually) on the people and objects around him, his wife, daughter, his studio, the painting he was working on, the view out the window, things lying on the table. He did over a hundred prints, then selected and re-selected until he ended up with forty-one; then arranged and re-arranged until he had them in the sequence he wanted. On the urging of his dealer, we put half the edition loose leaf in boxes, but he was never very satisfied with that. It was the bound book he cared for, thick and heavy and full of the air that had surrounded his life at that time (1963 to late 1965).228

Produces a series of seven lithographs, each featuring a seated female figure, with Original Press in San Francisco; Joseph Zirker, who worked with Diebenkorn at Tamarind in 1962, is the printer.229

1966

January: Visits Matisse retrospective at UCLA, where View of Notre Dame and French Window at Collioure (both 1914; see Elderfield essay, figs. 79 and 80) are exhibited for the first time in the United States.

26 February–May: Participates in Artists’ Tower of Protest (Peace Tower), organized by Irving Petlin, Mark di Suvero, and the Artists’ Protest Committee in Los Angeles, in protest against the Vietnam War.

May: Travels to France, West Germany, Holland, Denmark, and Austria with Phyllis and Joan and Richard McDonough. First visit to friends Bill (who met Diebenkorn in Hawaii during World War II) and Roselle Davenport at their second home near Aups in Provence.

17 May–4 June: Richard Diebenkorn: Drawings at Poindexter Gallery. Versions of this exhibition— groups of Diebenkorn’s figure drawings—tour to schools across the country, including the Kansas City Art Institute, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and Bennington College.

Completes his last painting in Berkeley. Large Still Life (cat. 3643) will hold a prominent place in the family’s homes for years to come.

155. Chimaise 1, no. 7 (1956). Discussion with Sam Francis, Claire Falkentstein, Lucas Calcagno, Frank Lobdell, and Mark Tobey in Paris.

156. In an interview with Nancy Boas, Paul Mills asserted that at the 1956 “California School, Yes or No?” forum, “Diebenkorn was one of the first to speak and he rather mildly made some statements in support of the idea of a San Francisco School,” while the other artists disagreed. “They were all caught up in the definitions of what a school means.” According to Boas, Mills “thought many artists in the audience felt the ‘school concept’ could be manipulated to create coherence, which undermined their preference for individuality.” Boas, Park, 185.

157. Diebenkorn to Poindexter, 13 Aug. 1955, Archives of American Art.

158. Stuart Preston, “Painting on View,” New York Times, 4 Mar. 1956.

159. R. R., “In the Galleries: Richard Diebenkorn,” Arts Magazine, Mar. 1956, 56–57; Dore Ashton, “Art,” Arts & Architecture, Apr. 1956, 11.

160. Richard Diebenkorn quoted in “Edging Away from Abstraction,” Time, 17 Mar. 1958, 64.

162. Jones, Bay Area Figurative Art, 27.

163. Landauer, Bischoff, 91.

164. Boas, Park, 201.

165. These photographs were published in Art News without a byline and remained unidentified until after Mandel’s death. Susan Ehrens, Director, Rose Mandel Archive, informed the Diebenkorn Foundation of Mandel’s authorship in 2011.

166. Richard Diebenkorn quoted in Herschel B. Chipp, “Diebenkorn Paints a Picture,” Art News, May 1957, 45–47.

167. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.

168. Ibid.

169. Richard Diebenkorn in response to a questionnaire from Alain Jouffroy and K. A. Jelenski for Preuves, Oct. 1956, RDFA.

170. Diebenkorn quoted in Schevill, “Richard Diebenkorn,” 22.

171. Dore Ashton, “An Eastern View of the San Francisco School,” Evergreen Review 1, no. 2 (1957): 158.

173. Aline B. Saarinen, “Benefit for the Fogg Museum,” New York Times, 7 Apr. 1957.

174. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.

175. Diebenkorn Faculty File, Office of the Provost, Mills College, Oakland, Calif.

176. Richard Diebenkorn quoted in Paul Mills, Contemporary Bay Area Figurative Painting, exh. cat. (Oakland, Calif.: Oakland Art Museum, 1957), 12.

178. Sarah Grissom, “San Francisco,” Arts Magazine, Feb. 1958, 22.

179. Arthur Millier, “West’s Artists Display Talent,”Los Angeles Times, 22 Sept. 1957.

180. Richard Diebenkorn quoted in Dorothy Gees Seckler, “Problems of Portraiture: Painting,” Art in America, Winter 1958–59, 34.

181. Dore Ashton, “Art,” Arts & Architecture, May 1958, 5, 29.

182. Poindexter to Diebenkorn, 7 Mar. 1958, Archives of American Art.

183. Diebenkorn to Poindexter, Mar. 1958, RDFA. No record of Diebenkorn’s Guggenheim application, other than a blank application form in the RDFA, has been found. He later served as a juror for the Guggenheim Foundation from 1979 to 1983.

184. Diebenkorn, interview with Larsen, 2 May 1985.

185. Diebenkorn quoted in Hofstadter, “Almost Free of the Mirror,” 61.

186. Lawrence Alloway, “London Chronicle,” Art International, Dec. 1958–Jan. 1959, 36.

187. Baker’s collection was shown across the United States, giving Diebenkorn’s work exposure and ultimately a home at the Yale University Art Gallery, to which Baker donated the collection.

188. Diebenkorn visited Santa Cruz Island almost every year, sometimes twice a year, until Stanton’s death in 1988. The Santa Cruz Island Foundation’s Richard Diebenkorn and Carey Stanton: A Private Collection gives a personal and detailed account of the two men’s friendship and the presence of the island in the Diebenkorns’ lives.

189. Irving Blum, interview by Lawrence Weschler, 1978, Center for Oral History Research, Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles. Audio recording, tape no. 3; transcript, 177.

190. Richard Diebenkorn quoted in William Steif, San Francisco News, 2 Sept. 1958, 9.

191. Alfred Frankenstein, “A Pacific Coast Style Defined by an Easterner,” San Francisco Chronicle, 12 Apr. 1959.

192. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.

193. Peter Selz, in conversation with Chester Arnold, moderated by Bart Schneider, 10 July 2013, Berkeley.

194. Jerrold Lanes, “Brief Treatise on Surplus Value; or, The Man Who Wasn’t There,” Arts Magazine, Nov. 1959, 30.

195. Richard Diebenkorn to Peter Selz, Museum of Modern Art, New York, n.d., at the time of organizing New Images of Man, 1959; quoted in Richard Diebenkorn, text by Gerald Nordland (Washington, D.C.: Washington Gallery of Modern Art, 1964), 18.

196. Diebenkorn gave Cajori a drawing, bearing the inscription, “Respectfully dedicated to my friend Charles Cajori who should be back again drawing with his friends in Berkeley. Best wishes for new year. Dick D. ’66” (cat. 3699).

197. Lydia Park quoted in Boas, Park, 248. For a more in-depth discussion of Park, see Boas.

198. Diebenkorn to Poindexter, Apr. 1960, Archives of American Art.

199. Eleanor C. Munro, “Figures to the Fore,” Horizon, July 1960, 16–24, 114–16.

200. Frank Lobdell: The Art and Making of Meaning (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2003), 321.

201. John Canaday, “Conducted Tour: Current Exhibitions Ask Questions on American Art and Offer Answers,” New York Times, 13 Nov. 1960.

202. In a 2013 conversation with Jennifer Field, researcher for the Willem de Kooning Foundation, Phyllis Diebenkorn acknowledges that this dinner occurred, but is unsure of the date.

203. Richard Diebenkorn quoted in Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture, essay by Allen S. Weller (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1961), 91.

204. Sidney Tillim, “Month in Review,” Arts Magazine, Apr. 1961, 46, 48.

205. Julian Levy to Diebenkorn, 23 Mar. 1962, RDFA.

206. Diebenkorn to June Wayne, 26 Sept. 1961, and Diebenkorn to Clinton Adams, 1 Apr. 1975, Tamarind Institute Records, Center for Southwest Research, University Libraries, University of New Mexico.

208. Symposium at UCLA in 1962 held as a tie-in with a show of Joann and Gifford Phillips’ collection, excerpts published in Frederick Wight, “The Phillips Collection—Diebenkorn, Woelffer, Mullican: A Discussion,” Artforum, Apr. 1963, 26.

209. Kathan Brown, Ink, Paper, Metal, Wood: Painters and Sculptors at Crown Point Press (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1996), 20.

210. “Spring Art Show to Open at CMF,” Vacaville California Reporter, 18 Apr. 1963, n.p.

212. Daniel Mendelowitz to Diebenkorn, July 1963, RDFA.

214. Poindexter to Diebenkorn, 6 Nov. 1963, Archives of American Art.

215. Valerie Petersen, “Reviews and Previews: Richard Diebenkorn,” Art News, Dec. 1963, 54.

218. Diebenkorn to Poindexter, 1964, RDFA.

219. For information on the Department of State’s cultural exchange program during the Cold War, see Frances Stonor Saunders, The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters (New York: New Press, 2000).

220. While they did not travel together, John Cheever and John Updike were also visiting the Soviet Union as a part of the program.

221. Department of State Grant Authorization Form, 10 Sept. 1964, RDFA; Phyllis Diebenkorn, undated interview.

222. Diebenkorn, interview with Larsen, 7 May 1985.

223. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.

224. John Ross to Carl Schmitz, 6 Dec. 2008, RDFA.

225. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.

226. Diebenkorn, interview with Larsen, 7 May 1985.

227. Nordland, Richard Diebenkorn (2001), 131–34.

228. Kathan Brown, in Crown Point Press at the San Francisco Art Institute, Emanuel Walter Gallery, 1 Sept.–1 Oct., 1972, exh. cat. (San Francisco: Institute, 1972), n.p.

229. Joe Zirker, in conversation with the author, 8 Jan. 2014. The press used by Zirker at Original Press is the same press later used at Collector’s Press by de Soto to print a later edition of lithographs. For more information on de Soto, see Jan Butterfield, “South of the Slot,” Art Gallery, Feb. 1975.