1966

Fall: Daughter Gretchen marries Richard Grant, a fellow Stanford student, at the chapel at Stanford University.

Moves with Phyllis in September to Santa Monica, where he begins teaching as a professor in the art department at UCLA. Diebenkorn met Fred Wight, head of the art department, in the Summer of 1961, after which Wight made numerous attempts to bring him to UCLA. Diebenkorn accepts the offer only after Wight promises him a position with minimal administrative and bureaucratic duties, a focus on teaching at the graduate level, and a flexible schedule to preserve Diebenkorn’s own studio time. Phyllis recalls that Diebenkorn accepted

because Fred Wight came up [to Berkeley] and offered Dick practically the moon to come. He was the head of the Department, and a fun, charming man. . . . And it came at a time when Dick was feeling that he needed a change and that things were getting pretty provincial. It was “funk art” time, when people [were] doing psychedelic paintings and taking a lot of dope and going like this [groovy gesture]. That’s what was happening in SF. The Summer of love and all that happened right before we left. He kind of wanted to get away from that.230

With the move to Southern California, Phyllis abandons her doctoral studies and dissertation research. She recalls,

I found a book of signs, medieval signs like they used to put on pottery and things like that. And there was a theory going around about complexity and simplicity and these signs were just perfect for that because they were everything from simple to complex. I was going to devise a test and then relate it to other things about people, to see if the more creative people chose the more complex signs. It was typical of the kinds of things people were doing. But the signs were very interesting and some of them were very beautiful. Dick thought they were great, too.231

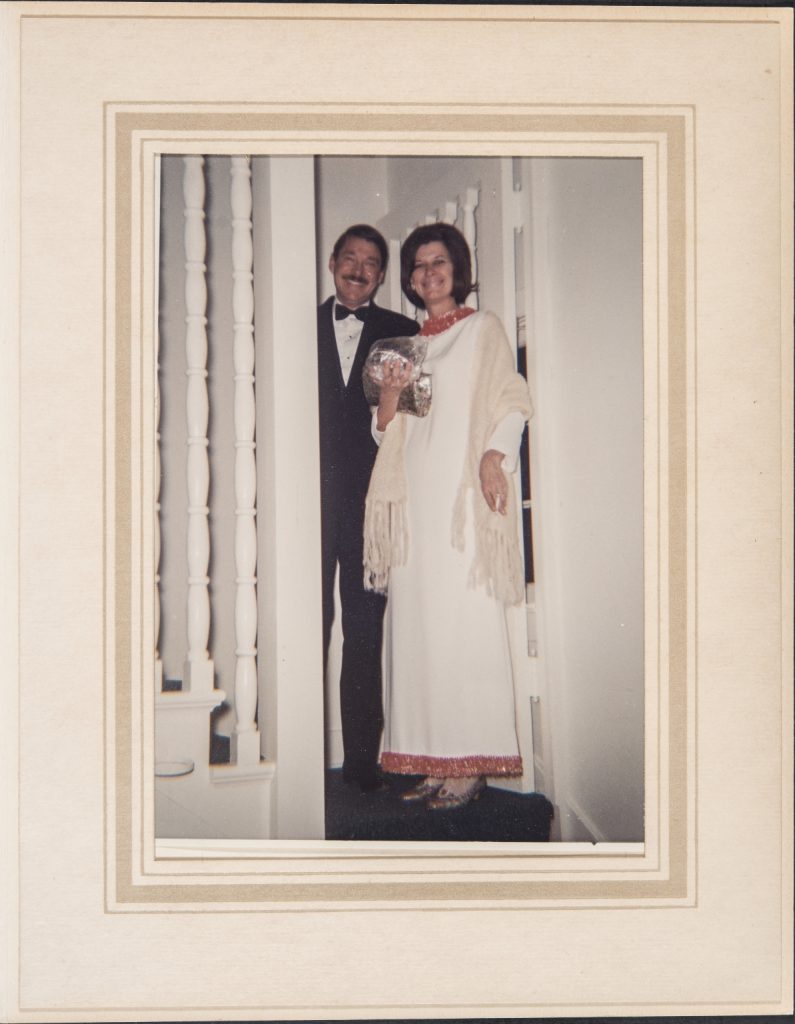

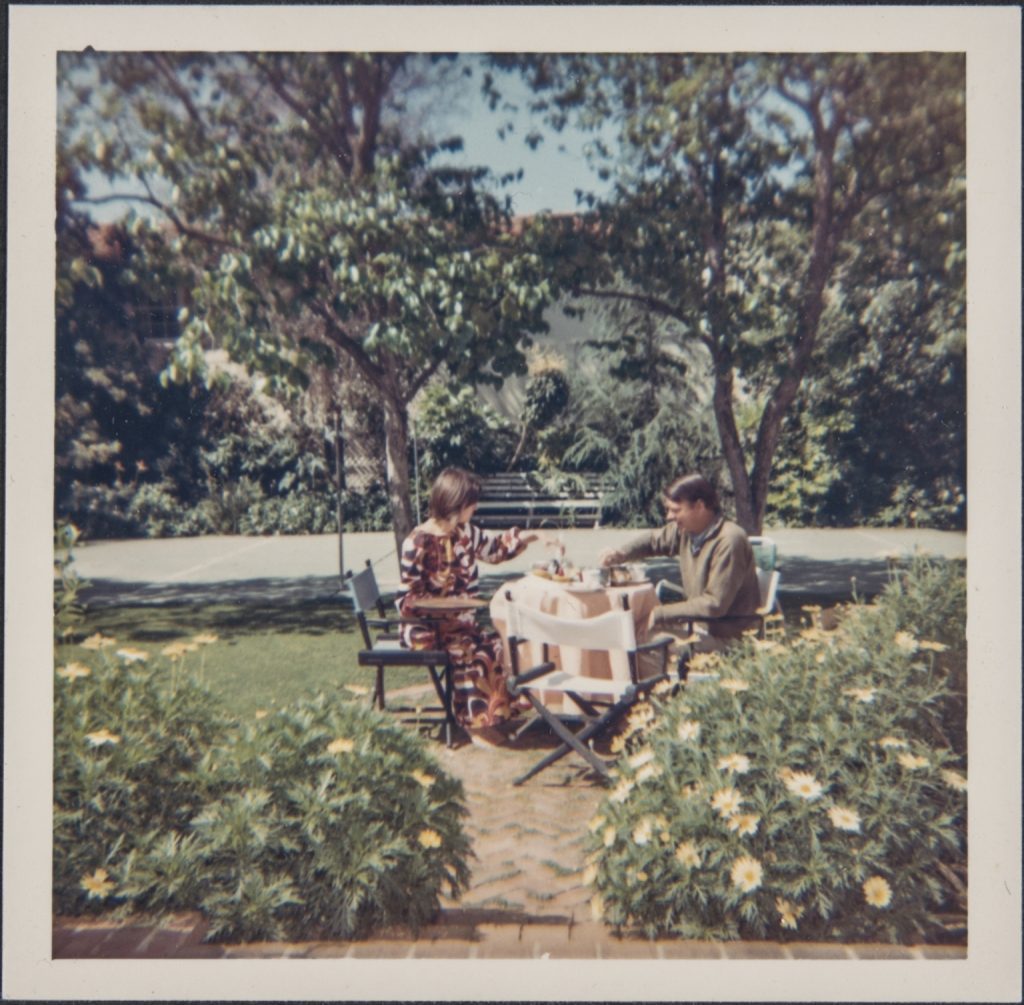

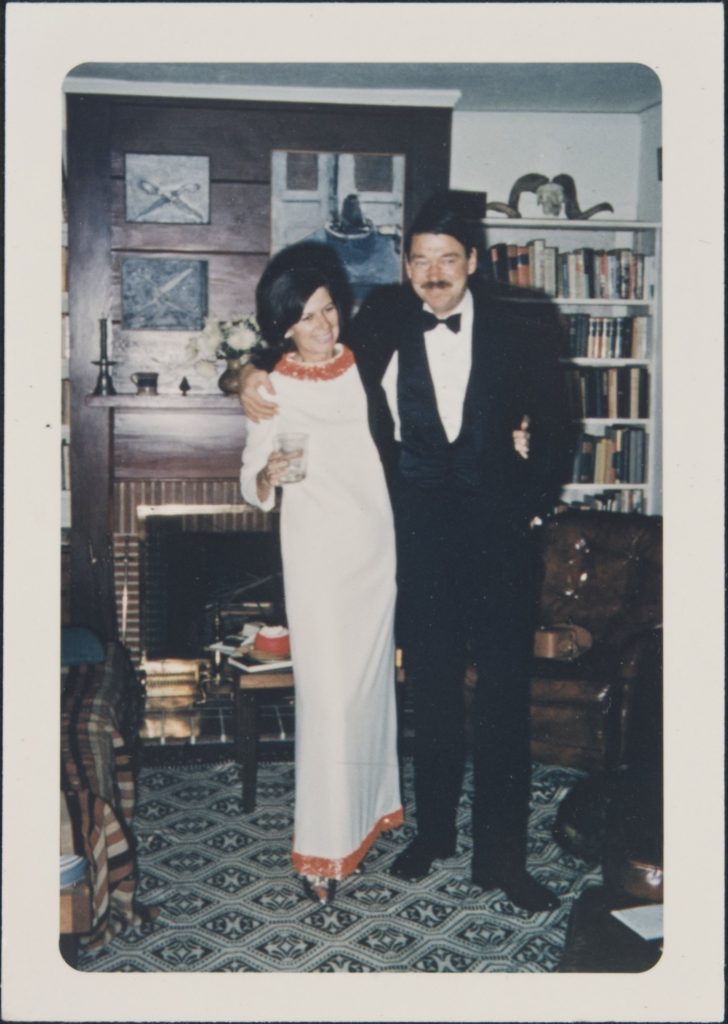

The Diebenkorns find themselves involved in a more active social life in Los Angeles, partly due to their close friendship with Bill and Shirley Brice. The Brices, along with Bill Brice’s brother-in-law, Hollywood producer Ray Stark, and dear friend Barbara Poe,232 invite them to Hollywood parties. Eventually Diebenkorn and Phyllis settle into a new intimate circle of friends. For the rest of their time in Southern California, they frequently see the Brices, Poe, Ann Rosener, Gifford and Joann Phillips, Maybelle Wolfe, Frank Perls, and Jascha and Julie Kessler. They remain close friends with fellow Bay Area transplants Theophilus “Bill” Brown and Paul Wonner, who had moved to Malibu.

The Diebenkorns rent a house, referred to by the family as the Blue Rug House, in Santa Monica near the beach.

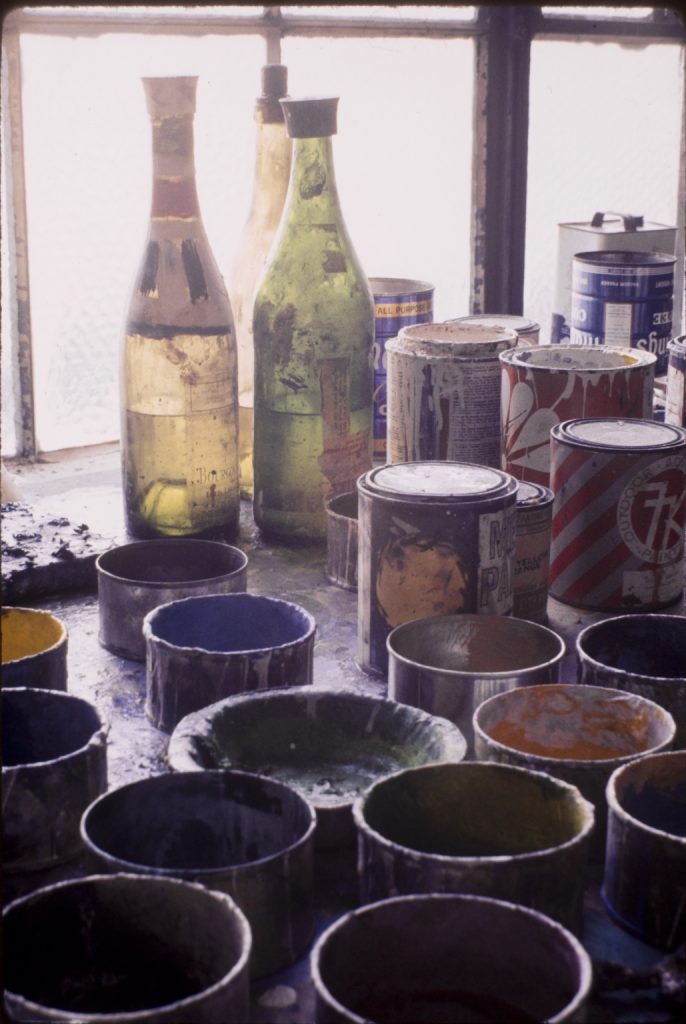

Sam Francis hears of Diebenkorn’s arrival and offers him his studio, as Francis will be vacating the space in a matter of months. It is a large second-floor studio in a two-story commercial brick building at the corner of Ashland Avenue and Main Street in the Ocean Park neighborhood of Santa Monica, a few blocks from the old amusement park on the pier.233 Diebenkorn uses a small windowless room in the center of the building as a temporary studio during his overlap with Francis. While waiting for the larger space, Diebenkorn works exclusively on paper, producing a distinctive and monumental group of female figurative drawings, some referencing his interest in the artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

I knew I wanted to be on the west side, to work out here because of the weather, sort of the clarity. I didn’t realize that it had a very special kind of light, that I discovered later. But at any rate, I had to wait in that studio . . . and the light was terrible. But it was okay for drawing. I didn’t try and set up, do oil painting there, but I drew for, oh, about eight months . . .234

President Lyndon Johnson names Richard Diebenkorn to the National Council on the Arts; Roger Stevens, the chairman, personally nominated Diebenkorn in 1965, the year that the National Endowment for the Arts was established. The early council includes Elizabeth Ashley, Leonard Bernstein, Ralph Ellison, Paul Engle, Herman David Kenin, Harper Lee, Agnes de Mille, Gregory Peck, William Pereira, John Steinbeck, Isaac Stern, George Stevens Sr., and Minoru Yamasaki. Diebenkorn frequently flies back from the East Coast with Peck and Pereira. During these early years of the National Council (founded in 1964), the group works on setting up the individual artist grant program. Phyllis will recall that Diebenkorn was a

reluctant public servant. . . . It wasn’t anything that mattered to him, because what mattered to him was what he did in the studio. But this was not difficult in the sense of taking up a lot of his time. He went back there for three days of meetings three times a year or whatever it was and that was that.235

Friend and artist Tony Berlant cites these frequent cross-country flights as a catalyst for Diebenkorn’s next body of work, the Ocean Park series.236

1967

12 January–4 February: Richard Diebenkorn: Works on Paper opens at Waddington Galleries in London. British critic Edward Lucie-Smith writes of Diebenkorn, “He is the representative of an American tradition which has been somewhat obscured for us, here in Europe, by the achievements of the New York School.”237

March: Elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters with Joseph Hirsch, William Thon, and David Burliuk. Included in Exhibition of Work by Newly Elected Members and Recipients of Honors and Awards at the institute, 25 May–25 June.

Spring: The Diebenkorns purchase and move into a house at 334 Amalfi Drive in Santa Monica Canyon, within walking distance of the ocean.

They bring most of their furnishings from Berkeley, including many objects that preceded their house on Hillcrest, re-creating a familiar atmosphere in their new home. This pattern repeats itself in each of their residences; their aesthetic is consistent and modest, and Diebenkorn’s works are the dominant hangings.

June: Diebenkorn moves into the larger studio at the Ashland Avenue and Main Street building. Francis will eventually return to the building, occupying the front space. Industrial rolled-steel pivot windows dominate the studio’s north wall.238 In a 4 May letter to Jack Lemon of the Kempner Institute, Diebenkorn writes, “Next month I’m promised a good studio here and my paintings should resume.”239

Ocean Park is a popular neighborhood for many Los Angeles artists’ studios and homes; Diebenkorn has a cordial relationship with many of them. As Tony Berlant recalls,

My house in Ocean Park was diagonally behind [Diebenkorn’s] studio. If I walked outside I could look up to the second floor and see his hand painting.

Dick’s building was at the corner of Ashland and Main Street in Ocean Park and is now a bank. There was a sail maker and Sam Francis in the front. In the back, there were Diebenkorn and Chas Garabedian. There were a lot of artists on Main Street and we would see one another. [James] Turrell was on the next corner; a bunch of UCLA people like Sam Amato and Les Biller were in storefronts, along with the bars and rescue missions. Other artists were in Venice, working in Billy Al Bengston’s building at Pacific [Avenue] and Mildred [Avenue].240

Summer–Winter: Immerses himself in the contemporary art around him; while avoiding openings, rarely misses a show at Nicholas Wilder Gallery and other galleries active during his time there—among them Ferus Gallery, David Stuart Galleries, 669 Gallery, Eugenia Butler Gallery, ACE Gallery, Margo Leavin Gallery, and later LA Louver, Rosamund Felsen Gallery, Asher/Fauer Gallery, and James Corcoran Gallery—trying to see as much art as he can. Associates with curators and gallerists including Walter Hopps, Irving and Shirley Blum, and later Maurice Tuchman and Jane Livingston; socializes with art dealers and patrons such as Frank Perls, Sidney and Francie Brody, and Stanley and Elyse Grinstein; and meets other artists, such as Robert Graham and Vija Celmins.

Among his students and younger colleagues at UCLA are Tony Berlant, Jim Doolin, Martin Facey, James Hayward, George Rodart, Don Suggs, and Elyn Zimmerman. His fellow teachers include William Brice, Charles Garabedian, Jan Stussy, Lee Mullican, Oliver Andrews, Gordon Nunes, Sam Amato, and Robert Heinecken. Berlant writes,

Dick Diebenkorn, my mentor at UCLA, almost never went to any art parties or openings. People like him are invisible. They’re part of the scene because their work is an inspiration. You don’t have to meet artists like that—it’s enough to know that they are living and working in the same city you are. Diebenkorn was social with a small group of people, mainly people he had gone to Stanford with and a few of his students. I was very lucky to be one of them.241

Continues painting representationally. Window (cat. 3906), the first painting completed in the new space, is one of the largest, at 92 inches tall.242

Completes Seated Figure with Hat (cat. 3908) and Seated Woman (see Elderfield essay, fig. 83), his last figurative paintings.243 These last figurative works evoke Diebenkorn’s recent immersion in Matisse and his continued movement toward flattening the picture plane.

Begins the abstract Ocean Park series with Ocean Park #1 (cat. 3978). The period will last until he leaves Santa Monica in 1988. The early nonobjective works, a break from the compositional constraints of the representational and the fight between interior and exterior space, are densely painted, employing bold areas of color in thick bands or pure blocks of space, with angles jutting into one another; unlike the final figurative paintings, the sections of the first Ocean Park paintings hold each other tightly together within the frame of the canvas. In an interview with Gail R. Scott, published with the first Los Angeles exhibition of Ocean Park works in 1969 at LACMA, Diebenkorn says of the change,

Even though my decision seemed sudden, that in a single day I said, “goodbye to all that,” I knew better. By the end of the first week it was clear that I was engaged in the same way as always, the same searchings for subject, the intense boredom, deceits and flurries of hope and excitement. . . .

The figure paintings were pretty much [architectonic]. I guess I’ve always been predisposed that way. Maybe it’s more that on its own now. It’s been a great release for me to be able to follow the painting in terms of just what I want for the painting, as opposed to the qualifying that I found I had to do in the figure painting.244

1968

January: Continues to be recognized for his representational works. Figure drawings tour extensively. Seated Woman wins the Carol H. Beck Gold Medal Award for Best Portrait from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts at the One Hundred Sixty-Third Annual Exhibition.

February: Has back surgery and is unable to paint for two months. While recuperating, works on second set of “fetish” objects (cats. 3964–69). These small three-dimensional composite objects resemble masks or tools and are made of wood, leather, metal, and paint, or whatever materials are close at hand.245

Hires younger artists to help him build his stretchers.246 Diebenkorn never hires a full-time assistant. Over the years he will work with Martin Facey, James Hayward, and George Rodart, among others.

Traditional painting begins to be called into question in American and European circles. Pop, Op, and land art and the Light and Space artists dominate the art scene in Los Angeles, while Diebenkorn and Sam Francis are considered the old masters of the city.247

11–30 May: First exhibition of Ocean Park paintings opens at the Poindexter Gallery. The change in style, while noted, does not provoke aversion or surprise, in contrast to Diebenkorn’s first figurative shows in 1957 and 1958.

22 June–20 October: Included in the 34th Venice Biennale.

9 November–29 December: Ocean Park nos. 9, 11, and 14 (cats. 3981, 3983, and 3985) appear in Untitled, 1968* at the SFMA, organized with the SFAI. Knute Stiles says,

Richard Diebenkorn’s new work is coming out of the flat surface of the canvas’s second dimension, too. One of his Ocean Park paintings still aspires to the illusion of depth. The other two Ocean Parks have certain references to a spatial possibility, but they are abstract illusions which will work either way, forward or backward. The figures are gone, and Diebenkorn has cleared the deck for change.248

12 December 1968–2 February 1969: A show of drawings opens at the Richmond Art Center. Diebenkorn selects the works and artist Tom Marioni, the curator of the Center, hangs the show. The Diebenkorns attend the opening.

21 December 1968–30 January 1969: An exhibition of twenty-six figure drawings opens at Poindexter Gallery.

Ceases drawing from the model. “I thought I would continue drawing from the figure indefinitely because for years it was so important to my painting.” 249

1969

Resigns from the National Council on the Arts after President Richard Nixon’s inauguration, and with the knowledge that Roger Stevens’s chairmanship will soon end.250 Writes to Stevens shortly before he leaves office,

Let me say that my certainty that the council was not a place for me has been mounting since my first meeting. Knowing that my talents and abilities for coping with Council business are minimal disturbs me deeply. I’ve written you two letters of resignation during the last year which I’ve destroyed. My final crisis came with Nixon’s announcement that business be encouraged to take over support of the arts, followed by learning at the last meeting of our date with the Business Committee for the Arts. On the surface of it it’s ridiculous for me to spook at this, but let me say that my original decision to become an artist was involved in part with separating myself entirely from “business”—for involved reasons. I will, I’m afraid rigidly, maintain that separation, even though a less emotional part of me could conceivably consider business to be art’s new, great patron. So you must see that it’s difficult—but it pains me to be difficult.251

3 June–27 July: New Paintings by Richard Diebenkorn opens at LACMA, introducing Los Angeles to the Ocean Park paintings; it is Diebenkorn’s first solo show in the city since 1960.

Fall: The Diebenkorns travel to Europe; they spend time in Holland, Germany, Spain, and Italy. In Italy they go to Florence to visit the Uffizi Gallery; Diebenkorn is drawn to Pietro Lorenzetti, Paolo Uccello, Piero della Francesca, and painted carvings and sculptures from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. They go to see Etruscan ruins, and visit Pompeii. In an unidentified questionnaire from 1969, Diebenkorn is asked, if he could own one piece of art, what it would be; he responds, “The City of Pompeii.” 252

After this trip Diebenkorn always looks for Lucas Cranach the Elder and Diego Velázquez in European museums.253

8 November–20 December: Richard Diebenkorn: The Ocean Park Series opens at Poindexter Gallery, which has moved to a new, smaller space, causing the paintings to appear cramped. Grace Glueck writes in Art in America, “Diebenkorn’s abstract renewal was, he has stated, as simple as a change of subject matter. Would that all simple changes had such rewarding effect.”254

Writes, “I continue to have absolute faith in painting’s near muteness. Its only convincing utterance arises from its simple, or complex—but unadorned— existence.” 255

1970

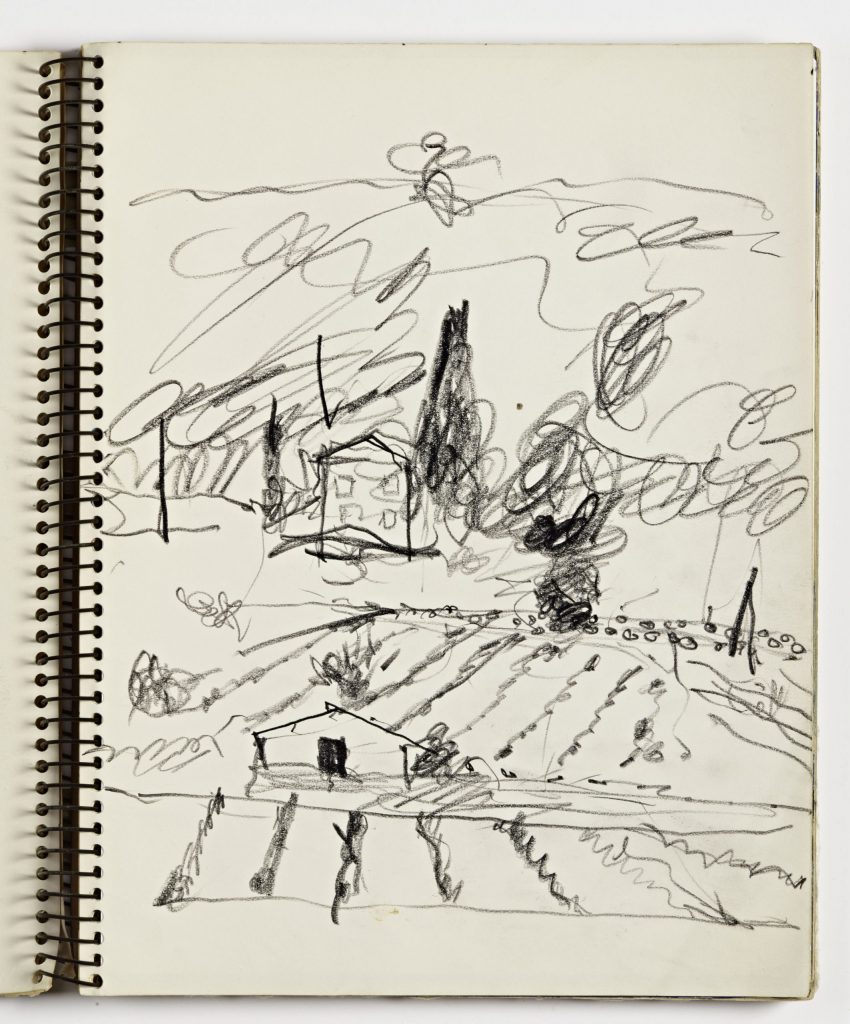

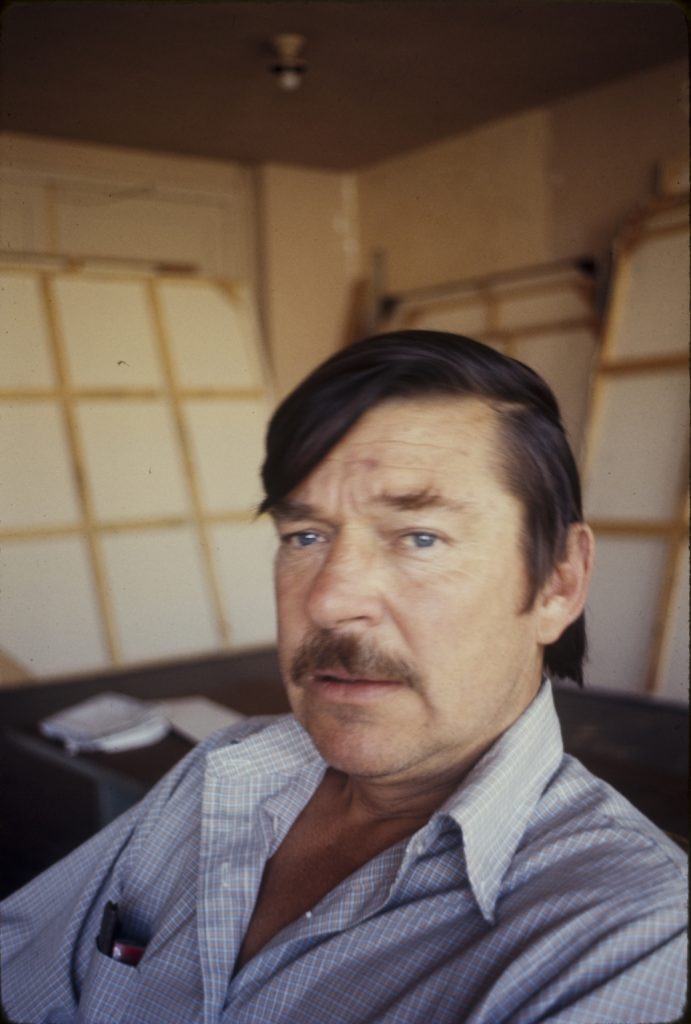

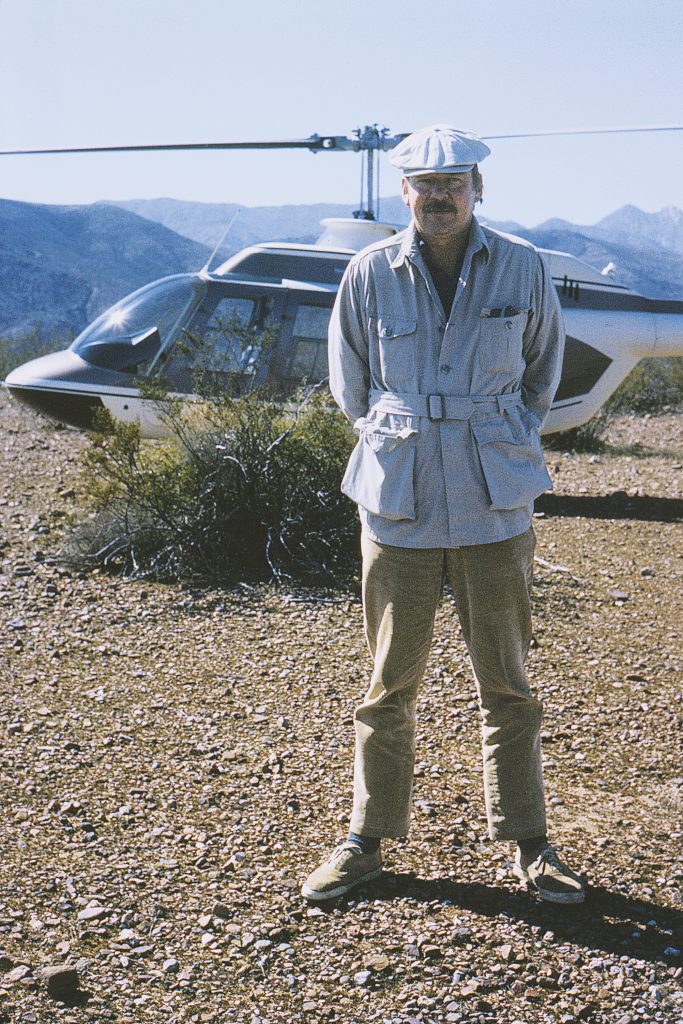

February: Participates in the Bureau of Reclamation and Department of the Interior’s project to document the water-reclamation sites in the Salt River Canyon in Arizona and in Colorado; John DeWitt organizes the program. Diebenkorn accepts the offer to survey the area and the commission to create artworks from what he observes, a rare acceptance as he dislikes commissions, considering the trip an opportunity to see the desert landscape aerially. He is flown over the area in a helicopter and takes numerous photographs during the flights. The Lower Colorado works, the first completed series of Ocean Park works on paper, are a result of this trip.

The project I was assigned to was the Salt River Canyon, in Arizona; we spent five days in a helicopter surveying it. In one place, we landed on the top of a towering pinnacle overlooking the river; the pinnacle actually had a surface of an acre and a half. I did some drawings—or, rather, paintings on paper—there; we were supposed to do documentary drawings, but mine came out as abstract impressions. I think the many paths, or pathlike bands, in my paintings may have something to do with this experience, especially in that wherever there was agriculture going on you could see process—ghosts of former tilled fields, patches of land being eroded. I also saw large areas where the fields were all planted in the same way for the same crop [but] showed unlimited visual variety. It boggled me! There was also circular farming: you could see clusters of concentric circles, made, I guess, by the combines, but they were cut in so many different ways that each was unique, surprising. Each was nuttier than the one before.256

11 April: Granddaughter Phyllis is born to Richard and Gretchen Grant.

Summer: Christopher marries Peggy Radin.

16 July–30 September: Dore Ashton organizes L’art vivant aux États-Unis at the Fondation Maeght in France, asking the artists to sign a pledge of dissociation from the U.S. government for their handling of Vietnam. Diebenkorn has difficulty signing, for while he is strongly against the war and the current administration, he will not disavow the government as a whole.257

Diebenkorn has a club-shaped pendant made for Phyllis from a necklace of Chilean coins.258

1971

12 January–28 February: Irving Blum hangs five Ocean Park paintings in his Los Angeles gallery. In a 1970 letter to Ellie Poindexter, Diebenkorn tells her that Blum came to his studio and asked for a small exhibition, and explains his reason for agreeing:

I find it important to have at least some of my new work shown locally before sending it away and I don’t think I can arrange a museum show as frequently as I have exhibitions with you.259

24 January: Decides to leave the Poindexter Gallery for more active representation. Diebenkorn has remained loyal to Ellie but due to the physical nature of his work—he strongly dislikes the way the large Ocean Park canvases look in her now low-ceilinged gallery—and the course of his career, he can no longer overlook that he has outgrown her gallery. He finds the decision tortuous.

Agrees to an exclusive five-year contract with Marlborough Gallery, which has courted him over the years, offering him their international presence, publications with color reproductions, and the potential to increase his visibility beyond the United States. In a letter to Ellie, he writes,

I’ve given a lot of thought and concern to a difficult decision over the past few weeks and I made up my mind. I know it’s a tough one for you not to have the show you counted on and I agree with you in your feeling that I should provide a substitution.

I want you to understand my reason for not having the March show and I want you especially to know that it’s not out of pressure from Marlborough—although, incidentally, they would like me not to have it. My reason is that I cannot set for myself a condition wherein I must work under pressure. I know you understand this about how I work. Assuming that my Marlborough decision this year isn’t the unwisest one, then I cannot insure for myself two years of work in my studio accompanied by thoughts of being successful, of being cautious, and requiring that my production looks “good.” I’ve never been able to execute a simple commission and for these same reasons.

I must turn over last year’s painting of which I’m confident, and should be more so by Summer, to my new agent and as quickly as possible return to my trial and error, slow and uncertain methods. . . .

I hope that it needn’t follow that acting in terms of one’s interests means crass and expedient behavior and I hope we can remain friends. You said on the phone, “I’m not mad” but I want it better than that.260

6 March–1 April: Fulfills his promise for a final show with Poindexter, with a small exhibition of drawings; it is the first exhibition of Ocean Park works on paper, and his last with the gallery.

Mid-March: Travels with Phyllis to New York to change dealers.261 Diebenkorn becomes good friends with Gilbert Lloyd, son of Marlborough Gallery founder Frank Lloyd; he enjoys spending time with Lloyd, and trusts him.262

Spring: Included in 6 at the Irving Blum Gallery, along with Sam Francis, Robert Irwin, Billy Al Bengston, Ron Davis, and Ed Moses.

Fall: Elected a Knight of Mark Twain by the Mark Twain Journal.263

20 September–7 November: Four Ocean Park paintings are shown at the Hayward Gallery in London. Jane Livingston and Maurice Tuchman, curators at LACMA, organize the exhibition, which travels to Brussels and Berlin. The show establishes Diebenkorn as a member of the contemporary Los Angeles art scene, and helps to further his international reputation.

4–31 December: First solo show at Marlborough Gallery, Richard Diebenkorn: The Ocean Park Series; Recent Work opens. The exhibition draws the largest critical response to date.264 Gerald Nordland quotes Diebenkorn in the essay for the exhibition’s catalogue:

When a painting is right and complete there is a cumulative excitement in the sequential encounters with the parts until the work is completely (or as completely as possible) experienced. The pitch of “right” response mounts, if the chain isn’t broken, to an extreme and often physical sympathy with the presentation.265

Diebenkorn sends him a note to thank him for his thoughtful analysis, and the two become friends.

Completes the “first period” of the Ocean Park paintings with Ocean Park #40 (cat. 4085).268

1972

Summer: Ocean Park #45 (cat. 4090) is shown at the Art Institute of Chicago’s Seventieth American Exhibition; Diebenkorn receives the Logan Medal of Art and the museum acquires the painting.269

Fall: Takes a semester-long sabbatical due to growing tensions within the UCLA art department, which is rife with political turmoil. Diebenkorn is hired with the promise of a schedule that focuses on graduate-level courses and spares him of administrative and departmental duties. His special circumstances aggravate a few other professors, and he finds himself assigned to classes and tasks beyond his initial agreement.270

29 September: Grandson Benjamin is born to Richard and Gretchen Grant.

1–31 October: Has first show with John Berggruen at his gallery in San Francisco.

14 October 1972–14 January 1973: Richard Diebenkorn: Paintings from the Ocean Park Series is exhibited at the SFMA. Nordland, the director of the museum, writes in the catalogue,

He has chosen . . . to utilize the primary ideas of painting in his time to recreate the tradition through the affirmation of the means of the painting art itself.271

1973

Winter: Request to reduce both his teaching commitments and his administrative duties at UCLA is met with rancor from other faculty members, who feel that the administration is privileging him within the department.272 The pressure begins to make teaching unpleasant. Diebenkorn’s teaching style is to focus on the individuality of the student; according to Bill Brice, “His painting classes were painterly, and tended to reach for the expansive.” He prefers not to grade on a traditional scale, and most enjoys the student reviews. Brice will later note that the administrative duties became burden-some for Diebenkorn, and that he wanted to “loosen things up.”273

January: The Diebenkorns become involved with organizing a potential retrospective at the Pasadena Art Museum with curator Barbara Haskell. Phyllis, who has always been trusted as a sounding board on aesthetic matters, increases her role in keeping records of her husband’s work.

Summer: The Diebenkorns travel to Europe, spending three days at the Prado Museum in Madrid and visiting Bill and Roselle Davenport in the South of France. Curator Jane Livingston will write about the effect of these travels abroad on Diebenkorn’s work, “What Diebenkorn absorbed in the European trips on 1969 and 1973 seems to have moved his work in the direction of greater and greater finesse. As the Ocean Park series progressed through the early 1970s, he cultivated increasingly harmonious chromatic effects, and the spatial, or planar, structure of the paintings became both more complex and less muscular, less architectonic.”274

June: A number of drawings are included in a show at the Robert Mondavi Winery in Oakville, Calif. The Diebenkorns travel to the opening and visit friends and family in the Bay Area.275

31 August: Submits his letter of resignation to UCLA. Earlier in the Summer he informed executive vice chancellor David Saxon that he would have to leave the university if forced to continue partaking in day-to-day classes and duties. The decision is difficult for Diebenkorn, but ultimately he chooses his studio, and leaves his last full-time teaching position.276 In his resignation letter to Saxon, Diebenkorn declines remaining with the special status the school is offering, as “[it] would be all but untenable and would be subject to unending ‘created’ problems. The destructiveness for me would be in exactly the area that I originally sought to preserve—my teaching, my relationship with students, and my own work.”277

Walter Hopps will later note that he “knew of no finer artist who chose to devote so much of his time to teaching.”278

October: Flies to the Bay Area to see the exhibition A Period of Exploration: San Francisco, 1945– 1950 at the Oakland Museum, curated by Terry St. John.279 Diebenkorn also sees an exhibition of Nathan Oliveira’s work while on the trip.280

December: Travels with Phyllis to London for the opening of Richard Diebenkorn: The Ocean Park Series; Recent Work at Marlborough Fine Art, returning before Christmas.281 The exhibition then travels to Zurich. John Russell writes the catalogue essay based on previous meetings with the artist.282

The show is met with mixed reviews, and Diebenkorn’s work has trouble catching on in Europe. Phyllis remembers that the exhibition

coincided with the terrible first oil crisis so that nobody had any lights on. I remember that we were in London for a month and we’d go to the museums every day and they would have one room with the lights on for 15 minutes, say, and then you could go to another room and they’d be on for 15 minutes. It was very frustrating. And there were no cabs available at all because nobody could get any gas. It was a very weird time to be there, and a very hard time to have your first big show in London. It was the same in the gallery—they would have their lights on for an hour and a half a day or something. . . .

It was very well received by the press and everything in London. John Russell wrote the catalog, and we got to be really good friends with [him], which was the best part of all. And then the show went to Zürich, where it bombed. Nobody could ever explain why, but nothing happened at all. It got bad reviews, and nothing sold, and nobody came—that we heard. We weren’t there. But, it just didn’t ring any bells with the Swiss, which was funny. And Marlborough was very embarrassed.283

The paintings in the exhibition highlight the changes in Diebenkorn’s work from the early Ocean Park paintings. The works are no longer dominated by the diagonal, but depend more on horizontal and vertical lines, and with a tendency to gather smaller sections toward the top of the canvas; the works become layered and ethereal grids, with individual chromatic universes and the development of scumbling and erasures.

1974

17 February–17 March: First retrospective of drawings, Richard Diebenkorn: Drawings, 1944– 1973, opens at the Mary Porter Sesnon Gallery at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Philip Brookman organizes the exhibition, working closely with Diebenkorn throughout the process. In a 2012 interview, Brookman will comment,

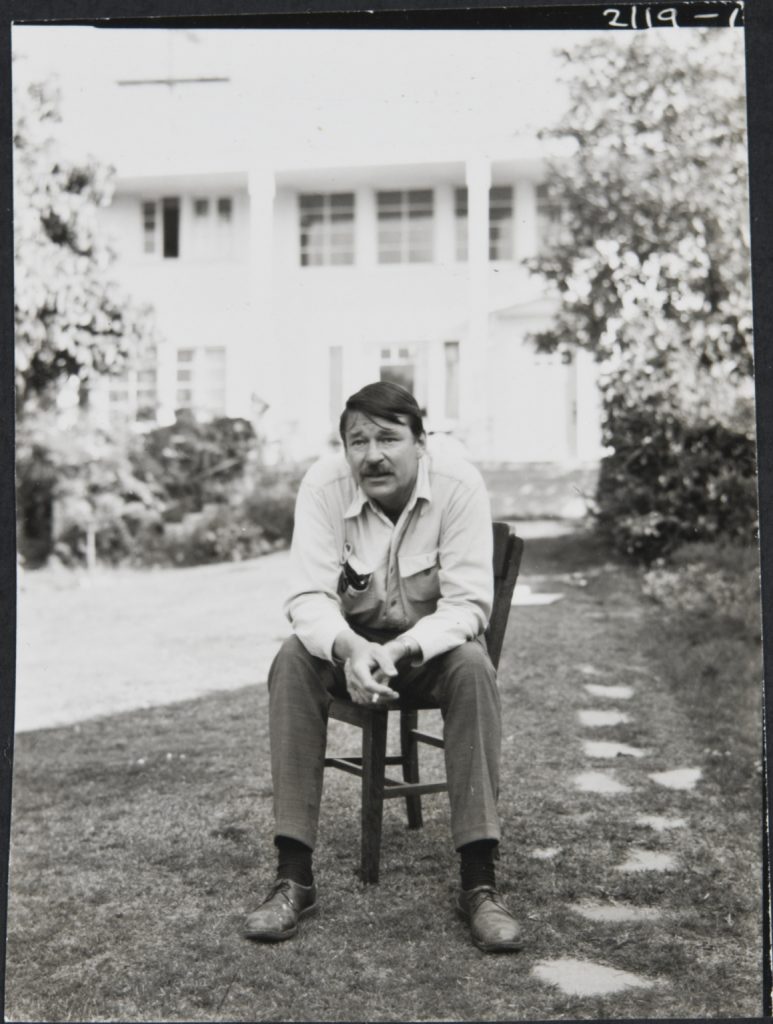

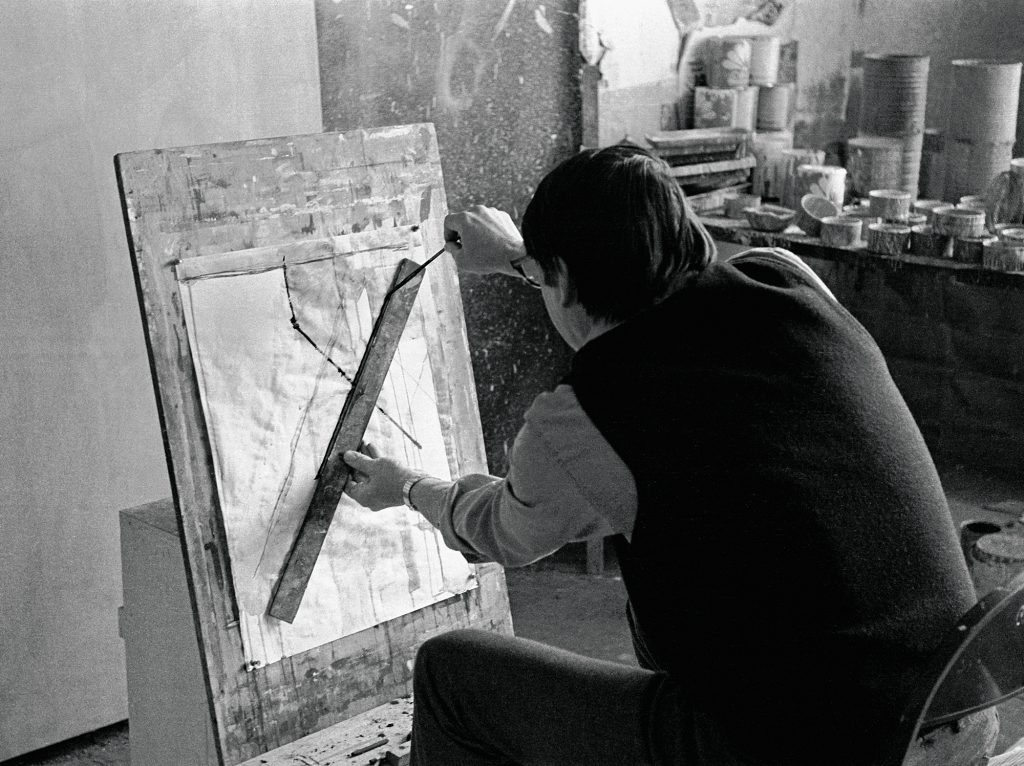

Diebenkorn was very generous with his time, maybe because I was just a kid then and he was used to playing the role of professor, although he had stopped teaching by then. He led a very middle-class life, with a wife and a dog and two grown kids. He drove to work at his studio every day. I was impressed with that ethic. I interviewed him about his work, and he let me photograph him drawing. He drew every day. He drew to clear his mind. We looked through many boxes of old drawings, and he helped me find drawings that had been sold or given away. This is how I learned what a curator does.284

The Diebenkorns attend the opening and visit Elmer and Adelie Bischoff while in Northern California.

27 February: The Diebenkorns purchase their second group of Indian miniatures at auction. Paul Wonner and Theophilus “Bill” Brown, also collectors of Indian miniatures, visit to see the new works.

Pasadena Art Museum, soon to be the Norton Simon Museum, cancels its planned retrospective.285

March: Works on a series of monotypes with George Page at the Sam Francis Lithography Workshop. The resulting series, Santa Monica M, contains thirty-six monotypes. Diebenkorn initially declines Page’s offer to produce an edition of lithographs due to his previous experience with the medium, and his lack of desire to push himself to become comfortable within its restrictions. However, he reconsiders after spending time with the catalogues of Nathan Oliveira’s monotype series Tauromaquia 21 and the Degas monotypes, and asks Page if he would work with him instead on a series of monotypes. Diebenkorn works with Page for ten consecutive days in March. As Nordland later writes,

Much of the drawing in the monotypes is worked directly in free hand but some lines are best achieved by laying in a line with a straight-edge. Occasionally, a line has to be positioned, erased, and redone a number of times before the searched for balance is attained. Esthetically, these variations on the Ocean Park theme are part of an effort to clarify and make precise the arbitrariness of art processes.286

13 March: Nellie Gilman Fryer, Phyllis’s mother, dies.

Summer: Buys two lots in Santa Monica, intending to build his own studio at 2444–2448 Main Street.

He works with architect Carl Day to design the space. The building will be two stories, with Diebenkorn’s studio on the second floor and a commercial rental unit on the first. The plan is simple, with cinder-block walls and clerestory windows to let in Diebenkorn’s preferred northern light.

The Diebenkorns often host visiting guests at their Santa Monica home—Kenneth Lash, the Davenports from Europe, Jack and Pat Falvey, Richard and Joan McDonough from the Bay Area, Gerald Nordland, and others.

1975

The Diebenkorns’ social life remains active throughout the 1970s. They frequently have dinner with the Brices at local restaurants, most often at Michael’s in Santa Monica; they also see Joann and Gifford Phillips, Barbara Poe, Bill Brown, Jascha and Julie Kessler, Irving Blum, and Fred and Joan Wight, and occasionally Susan and Ry Cooder and Edward Albee.

12 March–19 April: John Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco, and Jim Corcoran Gallery, Los Angeles, produce Richard Diebenkorn: Early Abstract Works, 1948–1955. In Art News, Thomas Albright will write,

These paintings, with their balance between gesture and structure, restraint and richness in color and handling, point ahead to Diebenkorn’s later figurative works and also to his more recent “Ocean Park” abstractions. They are “well-made” paintings, but then it has always been Diebenkorn’s virtue that, in an age which favors extremes, he has dared to be unspectacular.287

11–13 April: Produces his second large series of thirty-seven monotypes at Stanford with Nathan Oliveira. Oliveira, a painter and an experienced graphic artist, is skillful with the medium of monotype. The two artists work alongside each other with the aid of two students. In the works, Diebenkorn uses playing card pips and other symbolic figures. Along the bottom of an Ocean Park– esque monotype, he inscribes, “Take a good look, Dick—this is the bloody formula.” 288

23 May: Receives an honorary doctorate from SFAI. Travels with Phyllis to San Francisco for the ceremony.289

Construction begins at 2444–2448 Main Street, and will take almost a year to complete. Meanwhile, Diebenkorn continues to work in the studio at Ashland and Main.

Diebenkorn’s contract comes up for review with Marlborough Gallery. He decides not to renew after the gallery is found guilty of fraud in their longrunning lawsuit with the family of Mark Rothko after the artist’s death in 1970. In leaving, he joins Robert Motherwell, Philip Guston, and the estates of Franz Kline and David Smith. Despite his positive relationship with dealer Gilbert Lloyd, his concern over clouded dealings with an artist he greatly admired overshadows their friendship.290

20 November–9 December: Travels with Phyllis to the East Coast, stopping in Washington, D.C., and Buffalo before arriving in New York City for the opening of Diebenkorn’s final show at Marlborough Gallery, Richard Diebenkorn: The Ocean Park Series; Recent Work.

Begins to look for new gallery representation.

230. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.

231. Rudolf Koch, The Book of Signs (New York: Dover, 1950).

232. Poe is the daughter of Mark Rothko’s accountant and legal adviser, Bernard Reis. The Diebenkorns spent time with Reis when he visited Los Angeles.

233. Diebenkorn knew Francis through David Park, who met Francis while he was recuperating from a wartime injury during World War II at a hospital in San Francisco. Boas, Park, 88–90.

234. Elderfield, Drawings of Richard Diebenkorn, 201; Diebenkorn, interview with Larsen, 15 Dec. 1987.

235. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.

236. Tony Berlant, in conversation with the author and Carl Schmitz, 22 Apr. 2013.

237. Edward Lucie-Smith, “The Primitive and Exotic,” Studio International, Jan. 1967, 39.

238. In previous writings the windows have been incorrectly referred to as transom windows. A transom window is over a door or entryway.

239. Richard Diebenkorn to Jack Lemon of the Kempner Institute, 4 May 1967. Eventually Sam Francis returned to the building on Ashland and Main and worked in the front space on the second floor; Diebenkorn, interview with Larsen, 15 Dec. 1987. Extra rooms were occasionally rented to other artists.

240. Tony Berlant, from an interview with Richard Hertz, The Beat and the Buzz: Inside the L.A. Art World (Ojai, Calif.: Minneola Press, 2009), 22.

241. Ibid.

242. Diebenkorn’s canvases increased in size upon his arrival in the second Ashland and Main studio. Window and Seated Woman (see Elderfield essay, fig. 83) are the tallest figurative paintings that Diebenkorn completed.

243. Nordland, Richard Diebenkorn (2001), 144.

244. Richard Diebenkorn quoted in Gail R. Scott, New Paintings by Richard Diebenkorn, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1969), n.p.

245. Elderfield, Drawings of Richard Diebenkorn, 201.

246. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Maurice Tuchman, 10 May 1976, untranscribed tape, Maurice Tuchman interviews, 1976, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

247. For a perspective on Diebenkorn’s adherence to painting in the late 1960s, see Dore Ashton in Painting as Painting, preface by Donald B. Goodall, introduction by Dore Ashton, texts by George McNeil and Louis Finkelstein (Austin: Art Museum of the University of Texas, 1968).

248. Knute Stiles, “The San Francisco Annual Becomes an Invitational,” Artforum, Jan. 1969, 52.

249. Diebenkorn quoted in Scott, New Paintings by Richard Diebenkorn, n.p.

250. In an odd twist, Douglas MacAgy, Stevens’s deputy chairman, was appointed temporary chairman of the National Council on the Arts for six months, after Stevens’s departure.

251. Diebenkorn to Roger Stevens, c. Jan. 1969, and Diebenkorn, formal submission of resignation to President Nixon, 10 Mar. 1969, RDFA.

252. Diebenkorn statement, 1969, RDFA.

253. Livingston, Art of Richard Diebenkorn, 48.

254. Grace Glueck, “New York Gallery Notes: Open Season,” Art in America, Sept.–Oct. 1969, 116–18.

255. [Diebenkorn statement, Nov. 1969, RDFA].

256. Diebenkorn quoted in Hofstadter, “Almost Free of the Mirror,” 60–61.

257. Correspondence between Diebenkorn and Ashton, Winter–Spring 1970, RDFA.

258. The Chilean coins were given to Phyllis by friends Paul and Meme Harris; she wore the piece on a silver chain. Paul Harris lived in Santiago, Chile, with his family from 1961 to 1963.

259. Diebenkorn to Poindexter, 14 July 1970, Archives of American Art.

260. Diebenkorn to Poindexter, 24 Jan. 1971, Archives of American Art.

261. Datebook, Phyllis Diebenkorn, 1969–71, RDFA. The only known datebooks are for the years 1963, 1969–71, 1973–83, 1985, 1987, 1988, 1990, and 1991.

262. Nordland, Richard Diebenkorn (2001), 155.

263. Letter from Cyril Clemens, editor of the Mark Twain Journal, to Diebenkorn, 1 Sept. 1971, RDFA.

264. The Marlborough 1971 exhibition is the fifth solo show of Ocean Park paintings since the first showing at Poindexter Gallery in 1968. This exhibition was Diebenkorn’s most reviewed show to date.

265. Richard Diebenkorn quoted in Richard Diebenkorn: The Ocean Park Series; Recent Work, text by Gerald Nordland (New York: Marlborough Gallery, 1971), 10–12.

268. Livingston, Art of Richard Diebenkorn, 64.

269. Franz Schulze, “U.S. Art Today: Healthy, Lusty and Many-Colored,” Chicago Daily News, 24–25 June 1972.

270. For a thorough analysis of the culture at UCLA during Diebenkorn’s tenure and a presentation of his resignation, see Albert Boime with Paul Arden, The Odyssey of Jan Stussy in Black and White: Anxious Visions and Unchartered Dreams (Los Angeles: Jan Stussy Foundation, 1995), chap. 6.

271. Richard Diebenkorn: Paintings from the Ocean Park Series, text by Gerald Nordland (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Art, 1972), n.p.

272. Boime with Arden, Odyssey of Jan Stussy, 66–68.

273. Bill Brice, unpublished interview with Jane Livingston, May 1996, RDFA.

274. Livingston, Art of Richard Diebenkorn, 68.

275. Datebook, 1973.

276. Richard Diebenkorn to UCLA Executive Vice Chancellor David S. Saxon, 31 Aug. 1973, RDFA.

277. Ibid.

278. Walter Hopps, interview with Maurice Tuchman, 29 May 1976, untranscribed tape, Tuchman interviews, 1976, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

279. The show was accompanied by a book of the same name written by Mary McChesney. It includes numerous interviews with artists associated with the CSFA during the late 1940s.

280. Datebook, 1973.

281. Ibid.

282. Datebook, 1974.

283. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.

284. Interview with Corcoran chief curator Philip Brookman on the occasion of the opening of Richard Diebenkorn: The Ocean Park Series at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 30 June–23 Sept. 2012, http://www.corcoran.org/exhibitions/diebenkorn/brookman-interview (accessed 14 May 2014; site discontinued). A copy of this interview is located in the RDFA.

285. Nordland, Richard Diebenkorn (2001), 179; Datebook, 1973.

286. Gerald Nordland, in Richard Diebenkorn Monotypes (Los Angeles: Frederick S. Wight Art Gallery, University of California, Los Angeles, 1976), 6–7.

287. Thomas Albright, “Spin-Off,” Art News, Summer 1975, 113.

288. Nordland, Richard Diebenkorn Monotypes, 46–47.

289. Datebook, 1975.

290. Nordland, Richard Diebenkorn (2001), 179.