1950

Certain things were acceptable [at CSFA], certain things were out, and it was, like there was a way. You in some sense toed a line, and this bugged me a little bit. I wanted to get away and look at it by myself and do my own assimilation.83

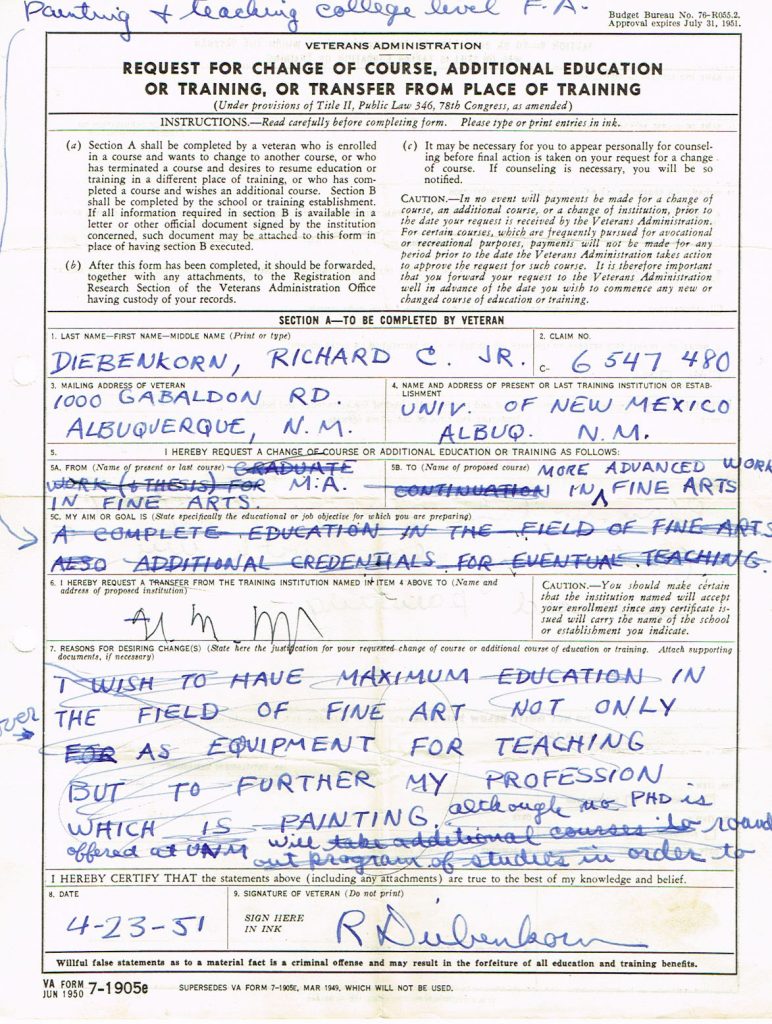

Using the rest of his GI Bill funds, decides to move to New Mexico with the hope of attending the University of New Mexico (UNM), Albuquerque, for a master of arts degree.84

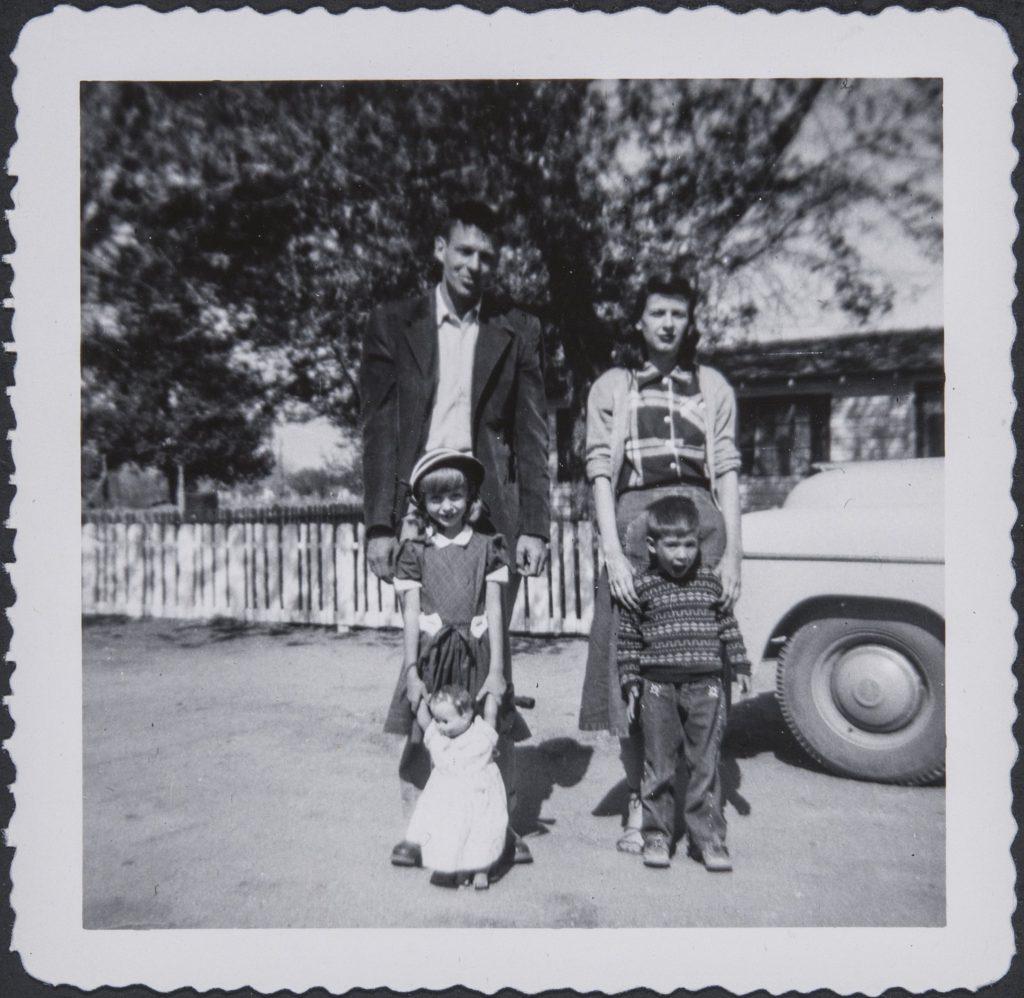

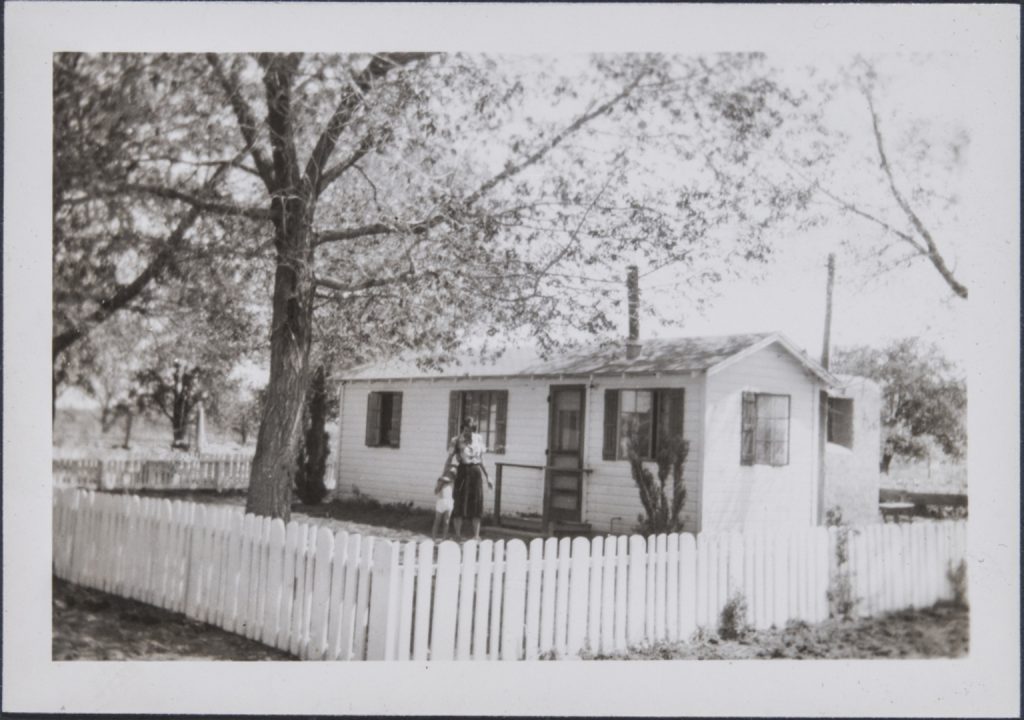

January: Family departs for New Mexico after classes end on 28 January. They spend a few weeks at the Hand Motel on Route 66 while looking for a place to live, eventually settling in a caretaker’s cottage on a large ranch at 1000 Gabaldon Road on the outskirts of Albuquerque. Farm animals and dusty fields surround the house, and a slough runs nearby; the property is less than a mile from the Rio Grande. Phyllis notes that Diebenkorn’s “urge for the big spectacular wide-open spaces” of the mesa is what draws them, not the university itself.”85

He chose Albuquerque because he’d been fascinated with the country there. And he loved [it], which I did too. It was really gorgeous. We spent every weekend, just about, driving around looking at stuff . . .

The land was red, and the mountains were spectacular. And the greenery, when it was there, was very very green with this very red earth. We’d go on picnics and go swimming—it was hot hot hot hot! In the Rio Grande various places with the kids and the dog. . . .

There wasn’t anything else to do. The only movies there were cowboy movies, and the only cultural activity at all was through the University [UNM]. There was music there and things like that. But it was really a western cow town.

The art department didn’t know what to do with Dick, so they didn’t really do anything. They kind of let him do his own thing.86

The art department at UNM is traditionally conservative, and a few professors are skeptical of Diebenkorn’s abstraction. Professor Raymond Jonson promotes advanced art at the school, and provides a venue for young local artists and students with his gallery on campus, the Jonson Gallery.87 Elaine de Kooning will later write,

Jonson is probably the factor most responsible for encouraging the large amount of work and the high level of professionalism of the young Albuquerque artists . . . by offering them one-man shows at his gallery. Without this goad, many of them feel they might have become too discouraged to go on in a vacuum. In his generosity, vitality and ability to stimulate other artists, Jonson is comparable to Hans Hofmann.88

Diebenkorn is formally accepted into the master’s degree program. Jonson finds him a private studio in a Quonset hut that belonged to the Physical Education Department after a few students begin to find Diebenkorn’s intense and active painting methods distracting; the artist is left to work with little interruption.89

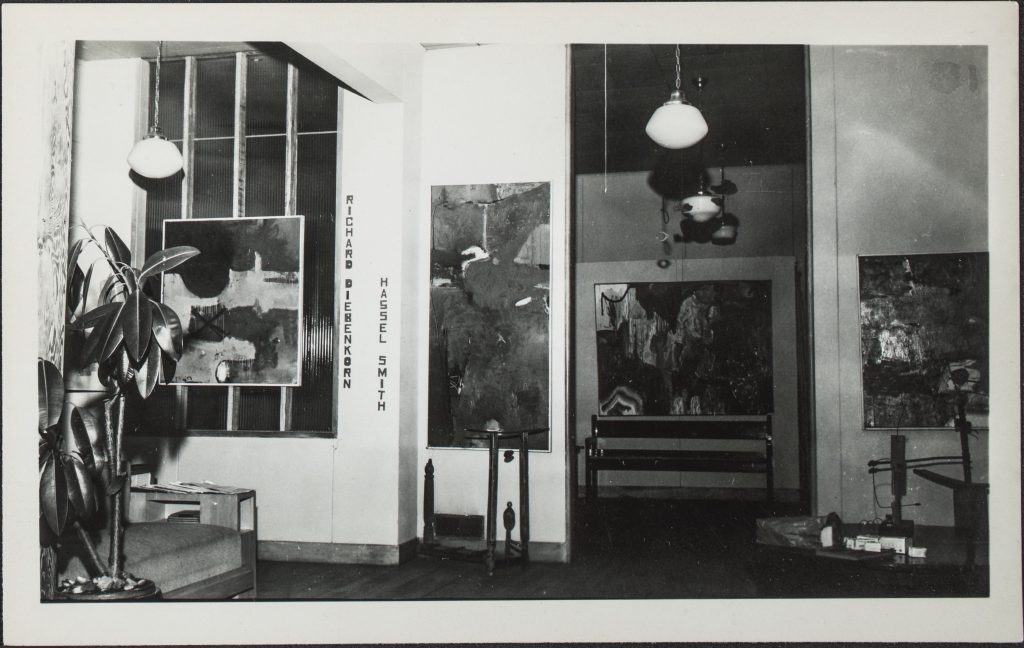

8–30 March: Featured with Hassel Smith in a two-man show at the Lucien Labaudt Gallery; does not return to California for the opening. Nan White interviews David Park for the San Francisco News regarding the exhibition:

Hassel and Dick would be the first to say they have no idea how they are going to paint next year. They are not fixed to one idea. If this leads to a different way of painting that may have a richer personal significance to them, they are in no way bound to continue in their present direction.91

May: Jonson selects Diebenkorn for a group show at the Jonson Gallery at UNM. Diebenkorn is also included in the 22nd Annual Exhibition of Student Work by the Graduate Students and Graduating Seniors of the Department of Art at the Fine Arts Gallery of UNM. He befriends other artists both in the department and around town, among them Alice and Jack Garver, Herb Goldman, Enrique Montenegro, and Adja Yunkers.

Summer: Paul and Josephine “Jo” Kantor visit the Diebenkorns; they purchase Untitled #22 (cat. 586) and begin to act as Diebenkorn’s de facto representation.92

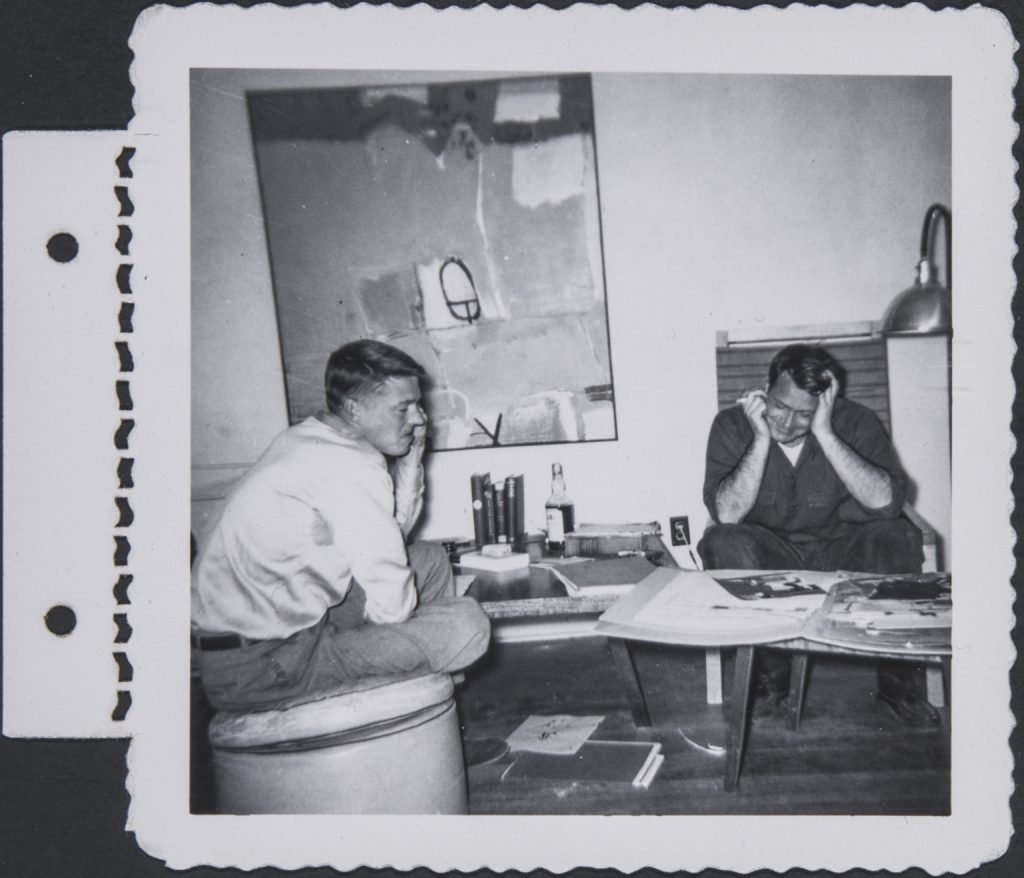

June: Lobdell writes Diebenkorn that Park has left abstraction and begun painting in a figurative manner.93 Later this month, Lobdell and girlfriend Annalise Korner visit the Diebenkorns. Lobdell and Diebenkorn paint together.94

July: Shows paintings in a group exhibition at La Placita, a restaurant in Old Town Plaza, Albuquerque.

Fall: Takes creative writing classes with Kenneth Lash, who remains a friend of the family for many years. Diebenkorn’s surroundings find their way into his work: the dusty colors, the geometry of the high desert, and the farm animals that live outside of his front door. Experiments with different media; creates linotypes and monotypes, paints a mural in an Albuquerque apartment, and learns to weld from Herb Goldman, completing two known iron sculptures.

1951

Phyllis and I both had thought, well, we couldn’t really live away from the water, the sea, too long, very long, so that was the apprehension when we moved back there, that there’d be no ocean. And well, the sky took the place of the ocean.95

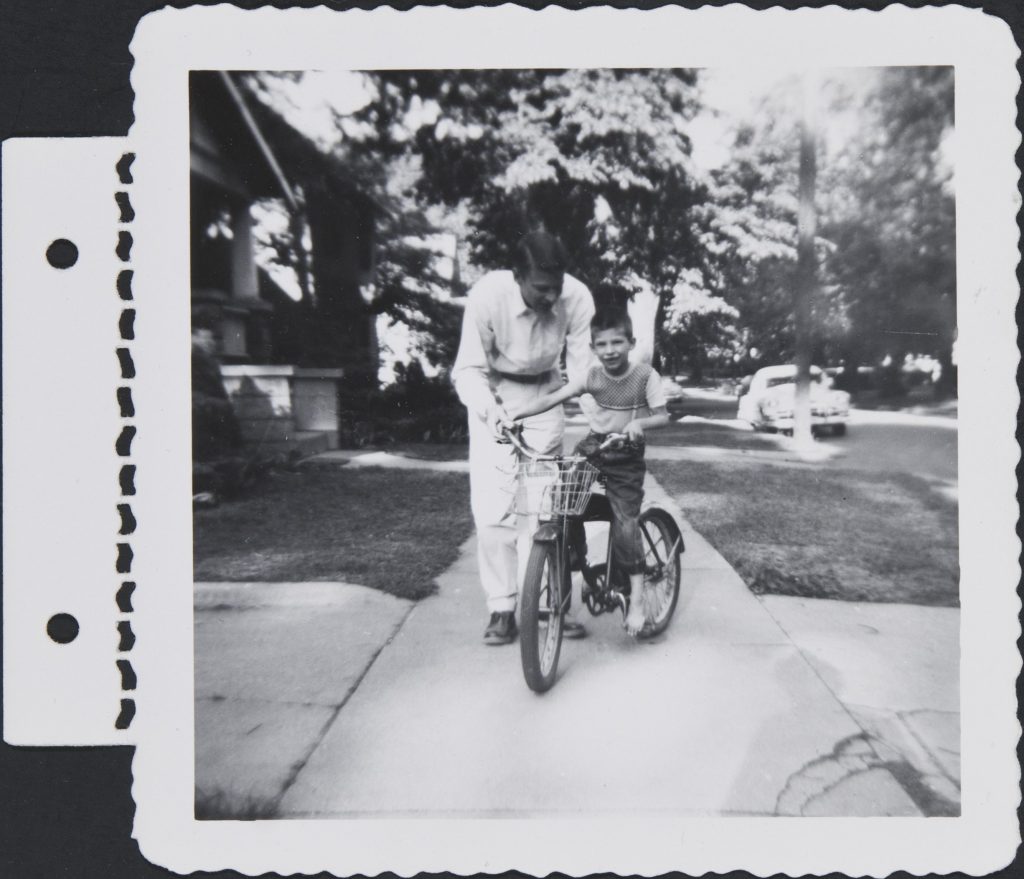

Edward Corbett arrives in Albuquerque and visits the Diebenkorns on his way to Taos, where he will enroll in Louis Ribak’s Taos Valley Art School on the GI Bill; Clay Spohn will join Corbett in Taos in April.96 Corbett confirms to Diebenkorn that Park has rejected abstraction and is “doing these kids on bikes.” Diebenkorn feels that “David did something really quite radical at that time.” 97

Critic Dore Ashton travels to New Mexico and visits Diebenkorn’s studio. As Ashton later recounts,

In the soft light of a New Mexican adobe house, where I had the good luck to see my first Diebenkorn painting, the image was of sandiness and desert: a horizonless flow of pale yellows, ochres and sand whites. . . . The painting . . . reflected not only his poetic grasp of the landscape before him, but also where he had been before. His studies at the California School of Fine Arts during the late 1940s had coincided with the advent of Clyfford Still and Mark Rothko. It was natural for him to explore new proposals for the projection of limitless space. He carried the experience with him to New Mexico. It is only one of Diebenkorn’s special talents to preserve and enrich experiences, evolving steadily at a harmonious pace. I don’t think he has ever left the desert behind.98

Spring: The family decides to stay in Albuquerque for another year. Diebenkorn applies for additional GI Bill funding; citing his desire to take classes in education, he attempts to make himself a more attractive hire at institutions for higher education.99 Phyllis continues to take courses in psychology at UNM.

Visits Corbett and Spohn in Taos on several occasions during his time in New Mexico.100 While in Taos, interacts with gallerist Eulalia Emetaz, who owns La Galeria Escondida.101

29 April–5 May: His master’s degree exhibition hangs in the Fine Arts Gallery at UNM. Corbett and Spohn help Diebenkorn install the show.102 The paintings reveal the intense growth the artist has experienced since leaving CSFA. The larger canvases, with their spiderlike lines, calligraphic forms, cut-out shapes, and broad areas of brushed color, depart from the stricter formal works and the use of outline.

An article in the Albuquerque Journal quotes the artist as saying, “[My] primary concern in painting is space, which to me is the most characteristic thing about New Mexico.” The large, blank areas in his paintings “reveal that openness of the desert, the vastness of the sky.” 103

Don Peterson writes on the exhibition for the student-run newspaper the Daily Lobo,

This reviewer . . . did not like the work. To him, the form used is new, strange, weird, and meaningless. . . . While the reviewer was looking at the exhibit, a few art students, and an instructor, descended upon him. Their opinions are worth noting: To them, the works are “amazingly convincing,” “a completeness in each one,” and “a new art form, a new means of expression, a new way of looking and feeling about life.”104

May: Receives master of arts degree from UNM.

Summer: Travels to San Francisco on his first commercial airline flight. While in the Bay Area, sees the Arshile Gorky memorial exhibition at SFMA (9 May–9 July). The combination of the views from the plane and the Gorky exhibition have a tremendous impact on Diebenkorn, a factor that he will openly acknowledge throughout the rest of his career.

I was absolutely knocked out and thrilled, really taken. I’d never taken a trip like that before. Flew fairly low over just all sorts of the country which just absolutely blew my mind.105

In a conversation with Nordland, Diebenkorn notes, “It wasn’t that I went right to the canvas and said I’m going to paint this but it just went right into the mill and started coming out strong.”106

2 June–22 July: Miller 22 (cat. 1104) is included in Contemporary Painting in the United States: 1951 Annual Exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum.

Summer: Paul Kantor travels to New York City to promote Diebenkorn’s work to dealer Sam Kootz and MoMA curator Dorothy Miller.107

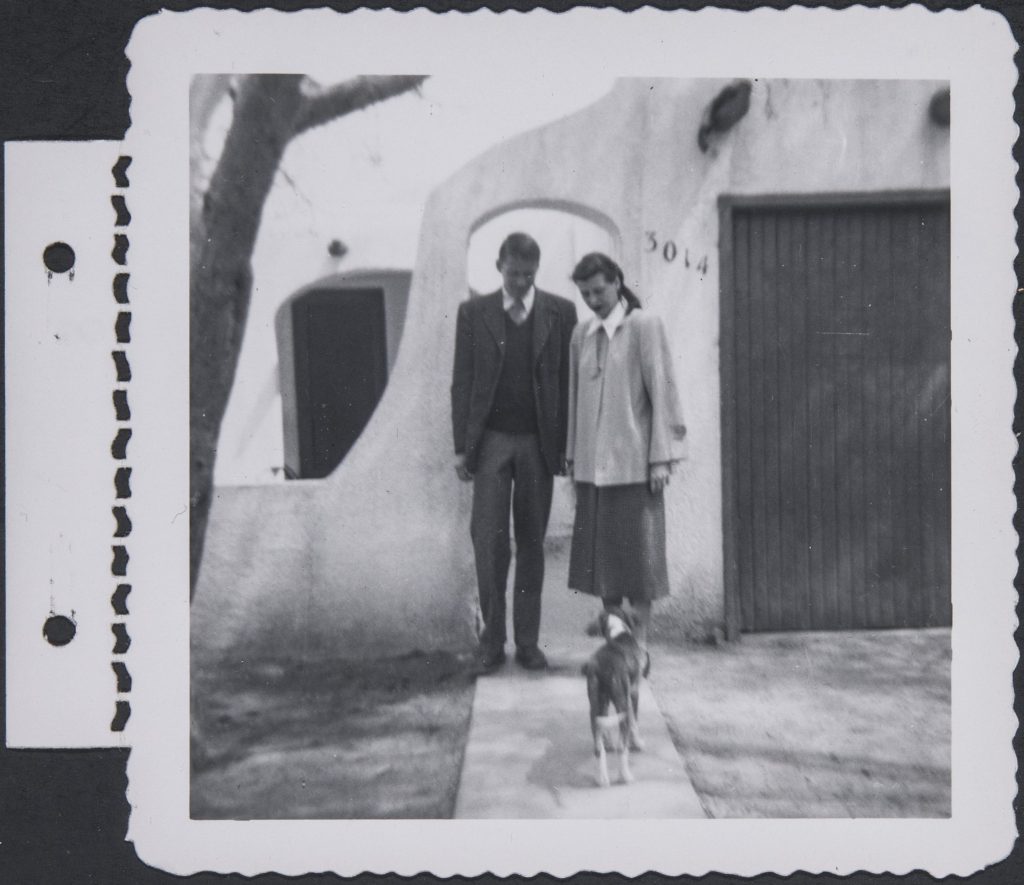

August: The family moves to a house in town, at 3014 North Edith Street, Albuquerque.

Fall: Moves to a new studio on campus, a temporary building housing the Speech Department.108

November: Frank Lobdell visits again. Diebenkorn and Lobdell discuss the possibility of working at Adja Yunkers’s planned art workshop, the Rio Grande Workshop, in Albuquerque. Diebenkorn seriously considers staying in New Mexico and working there as an instructor; however, the workshop folds and Diebenkorn is forced to look elsewhere for employment.109

Gerald Nordland and wife Mary visit the Diebenkorns and buy Albuquerque #3 (cat. 1095), which they pay for in installments. Phyllis recalls,

I have this vision of them—Jerry and his then-wife Mary—they were very young and they walked up the path to our house holding hands and rang the doorbell . . . and said, “We came to buy a painting” and we almost fainted. Just out of the blue. We had never met them and didn’t know they were coming. They just were there. They had seen the paintings at the LA County Museum show.110

Ad Reinhardt and Robert Motherwell publish Modern Artists in America, and select Untitled (cat. 755) for reproduction. Reinhardt, who taught at CSFA for the Summer of 1950, has been encouraged by Bischoff and Lobdell to look at Diebenkorn’s work. He is unable to stop in Albuquerque on his way back to New York, but the two artists share a brief correspondence, and Diebenkorn sends him slides of his recent work.111

1952

Winter: Phyllis completes her undergraduate degree in psychology.

Diebenkorn applies for teaching jobs across the country. Raymond Jonson and James Byrnes and Dr. William R. Valentiner of LACMA write recommendations. He tries to return to Northern California, but he cannot get in touch with Douglas MacAgy, who is indisposed with tuberculosis, and Erle Loran at UC Berkeley informs him that his department is out of money. He travels across the Midwest on a Greyhound bus, looking for jobs.113 The University of Illinois at Urbana is the only institution to offer him a position, which he accepts.

Summer: The family leaves Albuquerque and spends the Summer in California. Diebenkorn travels ahead by car with his paintings and the dog; Phyllis sells all of their belongings, including the furniture that Diebenkorn built by hand, and she and the children travel by train. They stay with Nellie and Roy Fryer, Phyllis’s mother and stepfather, at their ranch in Spadra, near Pomona. Diebenkorn works briefly at a paper mill, but quits after realizing that the machinery could severely maul his hands.114 He stores several rolls of Albuquerque paintings in a barn on Roy Fryer’s ranch; a few of the rolls are never retrieved.115

Sees Henri Matisse: Selections from the Museum of Modern Art Retrospective, selected by Alfred H. Barr Jr., organized by MoMA, and presented by the Los Angeles Municipal Art Department (24 July– 15 August).116 Diebenkorn purchases Barr’s monograph, which he will keep for the rest of his life.

Fall: Diebenkorn, Phyllis, and the children drive to Urbana, Illinois. They move into a large midwestern house with a coal furnace near the campus on Busey Avenue; Diebenkorn uses one of the bedrooms as a studio.

Assigned to teach beginning drawing to first-year architecture students at the University of Illinois. The department requires these students to take rudimentary drawing classes, and the professors in charge of the program implement a strict and formal curriculum, with its goal to train verisimilitude, precision, and discipline.117

Diebenkorn instead allows students to pursue their own directions and encourages personal creativity. In departmental group critiques, known as “judgments,” he receives negative feedback for his methodology. Don Weygandt, a graduate assistant in the art department at the time, will comment that Diebenkorn heard the professors’ criticisms and quickly put his students on the desired track.

The losing thing was that I’d find these people that I had pushed in a certain way, I was pushing them from a C to a D and, well, that was very bad of me. So I was uncomfortable about . . . how things were going there, and there was absolutely no moving either of these professors, and rightfully so. The architecture department said we want these people to learn to render and do so accurately and elegantly and . . . professors were following the prescription.118

The family bonds with the Weygandts—Don, Aldine, and daughter Suzy. Weygandt will remember Diebenkorn’s goal as being to teach each student “how to see.”119

The Diebenkorns become friends with their neighbors, musician and Urbana professor Stanley Fletcher and his wife Marian; the Fletchers introduce them to Henry and Gertrude Quastler. The Quastlers are Viennese immigrants; he is a doctor and medical researcher, she is an artist. The Diebenkorns host automatic drawing sessions in their home. Charles Shattuck, director of the University of Illinois Theater, occasionally recites literary pieces by Shakespeare, Brecht, and others for the couples, who use them to instigate their drawings, as Diebenkorn learned to do from David Park. Due to their friendship with the Fletchers, the Diebenkorns attend concerts on campus.120

Embarks on a productive and rewarding period of painting. Of the changes between the Albuquerque and Urbana works, he remarks:

They’re forms that I brought . . . with me from Albuquerque, mainly. But in Urbana the color things kind of came forth. In Albuquerque it was, as I said before, subdued, austere, black, gray, white. . . . And I don’t really, I don’t know quite how to explain that. It’s just something that a very different kind of environment produced.121

Diebenkorn will later mention that while the scenery in Urbana was more verdant than that in Albuquerque, the surroundings were “ ‘blotted out’ of his consciousness.” Diebenkorn blacks out the windows of his second-story studio, even though he ordinarily prefers working with natural light.122 His new works, like A Day at the Race (cat. 1242), Urbana #2 (The Archer) (cat. 1245), Urbana #5 (Beach Town) (cat. 1248), and the numbered Urbana paintings (cats. 1244, 1246–47, 1249), turn inward for color and use bold greens, blues, yellows, oranges, and pinks. Phyllis later comments on the flat, sunless quality of the landscape, and that unlike that of Albuquerque and later Berkeley and Santa Monica, the Urbana work was “almost like a rejection of the surround there, rather than an absorption.”123

Diebenkorn will later say,

Here I was in the Midwest, and I was pretty unhappy there because of all this ground and hay and stuff around, and then this painting occurred. I don’t know, a suggestion of a street and buildings and perhaps an ocean on the other side of these things, kept coming, insisting. So, I thought, well this is what I want to paint so I’m going to paint it. So, I did it.124

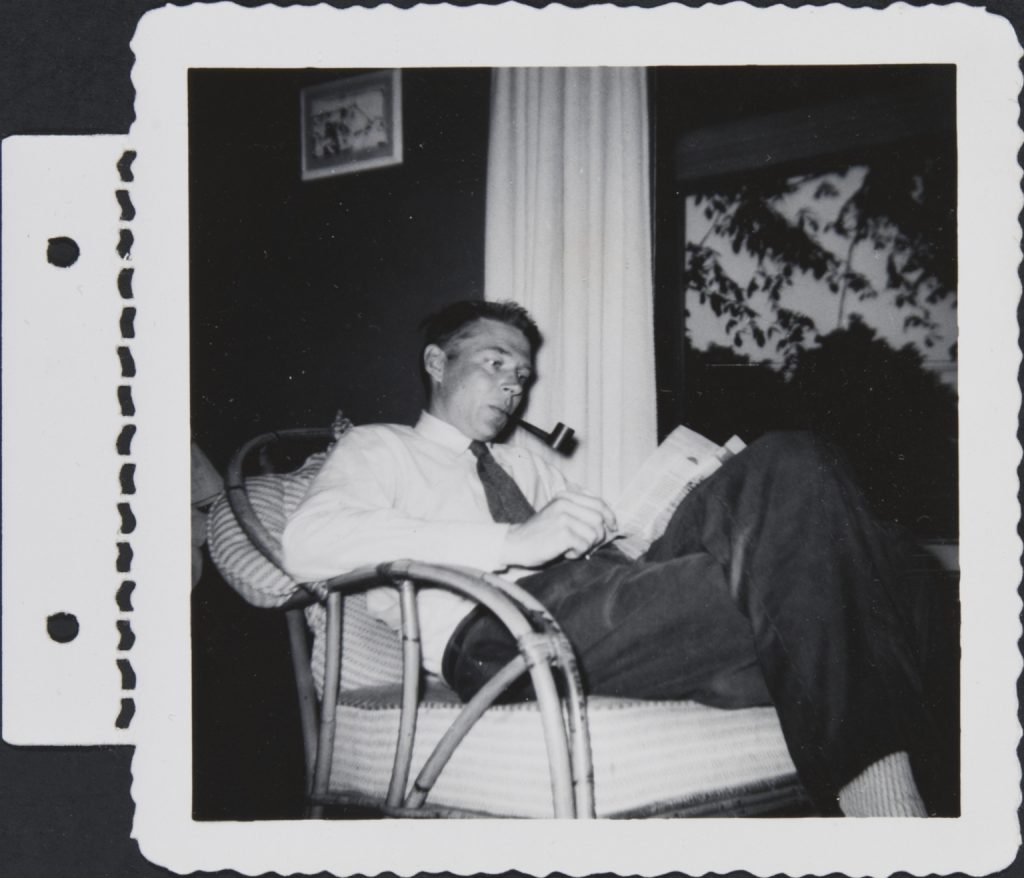

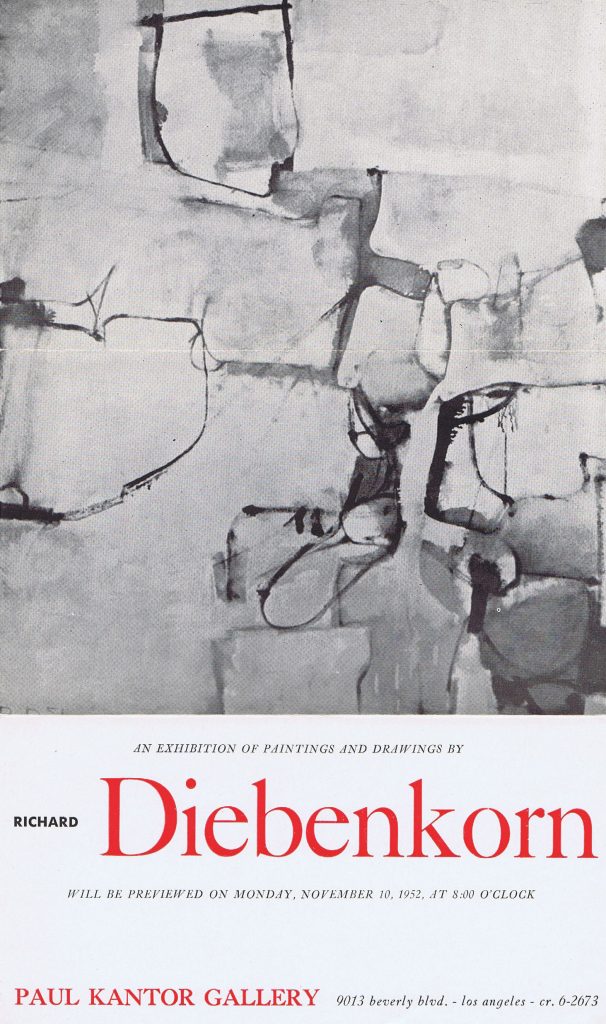

10 November–6 December: Richard Diebenkorn, first one-man show outside the Bay Area, opens at the Paul Kantor Gallery in Los Angeles. Arthur Millier, in the Los Angeles Times, calls him “one of the most gifted artists in the American nonobjective field.”125 The Green Huntsman (cat. 1163) is reproduced in Art News.126

Vincent Price buys Untitled (Albuquerque) (cat. 1159).127

Sometime during the winter the family leaves the house on Busey Avenue and moves to a new home at 713 West Illinois Street.

1953

March: Sees John Cage perform on the Urbana campus.128

April: The Carnegie Institute buys A Day at the Race, the first purchase by a major East Coast institution.

May: A Day at the Race appears in the inaugural exhibition of the Gallery of Contemporary Art at the Carnegie Institute. This painting is shown across the country, as the Carnegie lends the work each year until 1958.

4–30 May: Participates in the Exhibition Momentum Midcontinental at Werner’s Books in Chicago. Adolph Gottlieb, Richard Lippold, and Ad Reinhardt are jurors.

June: Leaves Urbana at the end of the school year. According to Phyllis,

Dick was not happy [in Urbana] because of the landscape. There was nothing to look at. It was just flat. . . . [The work] was suddenly very different. The colors changed. There was a lot of green in the paintings. It changed. I don’t associate the change as much with the surround as I did in Albuquerque, because the surround was not what inspired them—that was part of the trouble. . . . The outside was just not inspiring. And he was always very sensitive to what was out the window or out the door. And I know he knew within a couple of months that he was not going to stay in Urbana.129

The Diebenkorns drive to Manhattan with the family dog, Valentine; the children spend the Summer in California with their grandparents. They arrive in New York without a formal plan and stay in a “cheesy hotel on the Upper West Side the first night,”130 where their car is broken into. They rent Jon Schueler’s studio apartment at 68 East Twelfth Street for $75 a month; Diebenkorn works in the extra room. He spends time with John Grillo, Ray Parker, and John Hultberg; goes to the Cedar Tavern, where he meets critic Clement Greenberg and artists Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning; has his first contact with gallery owner Ellie Poindexte.131 Phyllis recalls,

We knew some people in New York and we met some more, and we somehow got together with Jon Schueler, who had been at the CSFA. . . . He rented us his studio. . . . It was an illegal living space on the second floor over an automat. It had a studio, and a room, and a sort of makeshift kitchen at the end of the room, which was strictly illegal. It consisted of a hotplate and a little refrigerator and a kitchen sink. It was . . . right on the edge of where everybody was in the art world at that time.

And Dick furiously began painting in the so-called studio, which was about a quarter the size of this room, but it was a space . . . we were kind of testing it out. And we knew we couldn’t handle the kids right at the beginning because we didn’t have any money. I was supposed to get a job and then we were going to find a place to bring the children. . . . So we visited various people, and the living circumstances of people in the [same] situation as we were was so terrible.

The couple begins to notice that their peers stay up all night and sleep late into the day, a habit they aren’t accustomed to. Diebenkorn’s preference for painting in natural light puts him at odds with a nocturnal lifestyle.

Stanford friend Carey Stanton is working at New York Hospital and lives in an apartment uptown; Stanton leaves each weekend and allows the couple to stay there to take advantage of his air conditioning. The Diebenkorns struggle financially and are unable to participate in the upper-class life of Stanton and other Stanford alums.

Phyllis continues,

I hated it. But Dick really wanted to go to New York. I don’t know exactly what happened to him, but I do know that one morning, in late August or early September, he came and he said, “pack up, we’re leaving,” and we left that day, and drove back across the country, to Berkeley. . . .

And we really didn’t like living from four in the afternoon till four in the morning. Partly because—when do you paint, you know? Especially, if you like daylight. But he never explained, he just said, “We’re leaving. Today.” and I said, “OK!” and we got in the car and drove home.

It was before the big burst of everything. We didn’t spend a lot of time in museums, because he painted all the time. I don’t [think] there is much intact from that Summer. There’s not a single painting that survived as a New York painting. I think he brought a few things home, but worked them over.

I suspect he probably thought that he could have worked there, but not with me and the kids. We were going to lose [Jon Schueler’s] place, which was supposedly great. It had a separate room to paint in. Most people were painting in the same room as they were sleeping and eating and the baby was crying. It was pretty grim. I don’t know if there was more to it or not.132

83. Diebenkorn, interview with Larsen, 1 May 1985. For further information, see Lavatelli, “Albuquerque Paintings of Richard Diebenkorn.”

84. In a letter dated 16 Jan. 1950, Bainbridge Bunting, acting head of the Department of Art at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, informed Diebenkorn that the group of painting instructors evaluating applicants did not feel that photographs alone would suffice when they reviewed his work. Bunting encouraged Diebenkorn to send a physical example, and apologized for the difficult situation. He also mentioned that painting professor Raymond Jonson was “especially interested in your things.” RDFA.

85. Phyllis Diebenkorn to friend Marge Allan, February 1950, RDFA.

86. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.

87. A few members of the UNM faculty did not believe that Diebenkorn was ready for graduate work. He sat in on a few figure-drawing classes with Professor John Tatschl; these works were submitted to department chairman Lez Haas for review, and Haas and the faculty decided that Diebenkorn was prepared and fully accepted him into the program. Lavatelli, “Albuquerque Paintings of Richard Diebenkorn,” 64. Gerald Nordland, Richard Diebenkorn in New Mexico (Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 2007), 20.

88. Elaine de Kooning, “New Mexico” (1961), in The Spirit of Abstract Expressionism: Selected Writings (New York: George Braziller, 1961), 186.

89. Lavatelli, “Albuquerque Paintings of Richard Diebenkorn,” 24–25.

91. Nan White, “Free Form Abstractions Stir Up Controversy in This Area,” San Francisco News, 18 Mar. 1950.

92. Paul Kantor, interview with Maurice Tuchman, 6 May 1976, untranscribed tape, Tuchman interviews, 1976, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

93. Frank Lobdell to Richard Diebenkorn, 1 June 1950, RDFA. In his book The New Figurative Art of David Park (Santa Barbara, Calif.: Capra Press, 1988), Paul Mills quotes Diebenkorn as saying, upon hearing the news of Park’s switch to figuration, “My God, what happened to David.” Diebenkorn told this story to Mills in the early 1960s when the author was researching his master’s thesis on Park at UC Berkeley, and the quote has since appeared in numerous publications. Gretchen Diebenkorn Grant clarifies the statement by explaining that her father was not dismayed, but rather confused and intrigued. Previously, the timeline has acknowledged Edward Corbett’s visit in the beginning of 1951 as the moment Diebenkorn discovered Park’s transition, but the letter from Lobdell predates that meeting.

94. Lobdell to Diebenkorn, 1 June 1950; Diane Roby and Anthony Torres, “Illustrated Chronology,” Frank Lobdell: The Art of Making and Meaning (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2003), 313; Frank Lobdell, interview with Maurice Tuchman, 13 May 1976, untranscribed tape, Tuchman interviews, 1976, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

95. Diebenkorn, interview with Larsen, 2 May 1985.

96. After Diebenkorn left for New Mexico in 1950, the “golden era” of the CSFA began to come to a close. With funding from the GI Bill dwindling, the board was forced to make decisions to keep the school solvent. MacAgy and Clyfford Still both resigned; reacting to a new plan to consolidate instructorships, Corbett resigned upon the threat of dismissal. For an in-depth discussion see Landauer, Edward Corbett, 120 and chap. 5.

97. Diebenkorn, interview with Larsen, 2 May 1985.

98. Dore Ashton, “Richard Diebenkorn’s Paintings,” Arts Magazine, Dec. 1971–Jan. 1972, 35.

99. Veterans Administration form “Request for Change of Course, Additional Education or Training, or Transfer from Place of Training,” 23 Apr. 1951, RDFA.

100. Landauer, Edward Corbett, 53.

101. Richard Diebenkorn to Phyllis Dorset, 10 Feb. 1987, Center for Southwest Research, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

102. Ed Corbett and Clay Spohn to Richard and Phyllis Diebenkorn, 3 May 1951, RDFA. Corbett wrote, “Huzzah for your paintings, Dick, which are very necessary.” Richard Diebenkorn to Clay Spohn, postcard, 7 May 1951, Clay Spohn papers, ca. 1862–1985, bulk 1890–1985, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

103. Richard Diebenkorn quoted in “Diebenkorn’s Art Is Shown,” Albuquerque Journal, 2 May 1951, 8.

104. Don Peterson, “Diebenkorn Show Has 18 Art Objects,” New Mexico Daily Lobo, 1 May 1951.

105. Richard Diebenkorn, interview with Mark Lavatelli, 11 Nov. 1978, in “The Berkeley Paintings of Richard Diebenkorn” (unpublished paper, University of Dallas, 1985), 21n11.

106. Diebenkorn quoted in Nordland, New Mexico, 32.

107. Paul and Jo Kantor to Richard Diebenkorn, 1951, RDFA. The Kantors discuss curator Dorothy Miller’s consideration of Diebenkorn for the exhibition Twelve Americans, at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 30 May–8 Sept. 1956.

108. Nordland, Richard Diebenkorn (2001), 37.

109. For more information on the Rio Grande Workshop, see Joan Evans, “Yunkers Opens Artists’ Workshop; Courses in Prints and Painting,” Albuquerque Journal, 29 Apr. 1951; and Dick Wilbur, “Jury Receives Art Training at Trial of Yunkers’ Suit,” Albuquerque Journal, 11 May 1952.

110. See Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant; Gerald Nordland to Richard Diebenkorn, 1951–52, RDFA.

111. Ad Reinhardt to Richard Diebenkorn, 8 Sept. 1951, RDFA.

113. Richard Diebenkorn to Murray Hickey Ley, draft, 1952, RDFA. Nordland, Richard Diebenkorn (2001), 23.

114. While one version of the story is that Diebenkorn witnessed an accident at the mill in which a machine mauled a man’s hand, Gretchen Grant recalls that her father quit working at the factory after realizing what the risks were. The family later heard of a man who worked the line with Diebenkorn and lost a limb in the machines shortly after Diebenkorn left the factory.

115. The number of rolls that were left and later recovered has not been confirmed. Diebenkorn said that two of three rolls were never retrieved (interview with Larsen, 2 May 1985); Nordland, that one of three rolls was never retrieved (Nordland, Richard Diebenkorn [2001], 54). Diebenkorn reviewed Nordland’s manuscript before it was sent to press. Phyllis later told Nordland that she uncovered one of the rolls, but one remained missing. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Nordland, 19 Aug. 1995, Gerald Nordland Papers, RDFA.

116. Walter Hopps remembered this show clearly, according to his 29 May 1976 interview with Maurice Tuchman. The show did not take place in a museum but in a commercial space at, according to Hopps, the “5600 block of Wilshire.”

117. Diebenkorn, interview with Larsen, 2 May 1985.

118. Ibid.

119. Don Weygandt, interview with Maurice Tuchman, 23 May 1976, untranscribed tape, Tuchman interviews, 1976, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

120. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant; Richard Diebenkorn to Mary Schmidt, 15 Feb. 1982, unknown archive.

121. Diebenkorn, interview with Larsen, 2 May 1985.

122. Tuchman, “Diebenkorn’s Early Years,” 18.

123. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Maurice Tuchman, 10 May 1976, untranscribed tape, Tuchman interviews, 1976, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

124. Richard Diebenkorn quoted in “Diebenkorn, Woeffler, Mullican: A Symposium,” Artforum, Apr. 1963, 27.

125. Arthur Millier, “Romantic-Abstract Work Well Integrated,” Los Angeles Times, 16 Nov. 1952.

126. The work was misidentified as “B” in Jules Langsner, “Art News from Los Angeles,” Art News, Nov. 1952, 60–61. According to Phyllis Diebenkorn, in conversation with Andrea Liguori on 14 Aug. 2012, The Green Huntsman was named after the Stendhal book of the same name, which Diebenkorn was reading while he painted the work. Diebenkorn asked Phyllis for a title, a rare occurrence, and she suggested using the Stendhal title. He always considered the title a joke rather than a connection to the meaning of the novel.

127. Vincent Price, I Like What I Know: A Visual Autobiography (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1959), 230–31.

128. While on campus Cage gave a lecture, “Music for Magnetic Tape,” and brought with him tape recordings of other contemporary composers. Marilyn Meyer, “Contemporary Arts Festival Begins Whirlwind Program with Dance Group Tonight: Modern Composer to Talk Saturday,” Daily Illini, 8 Feb. 1953.

129. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.

130. Ibid.

131. Franz Kline has been credited as Diebenkorn’s link to Poindexter by Caroline Jones in Bay Area Figurative Art, 1950–1965, exh. cat. (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1990), 184. However, others have also claimed that role, including James Byrnes, 22 May 1976, Maurice Tuchman interviews; Paul Kantor, 1952 correspondence with Diebenkorn, RDFA; and Budd Hopkins, 1956 correspondence, RDFA.

132. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.