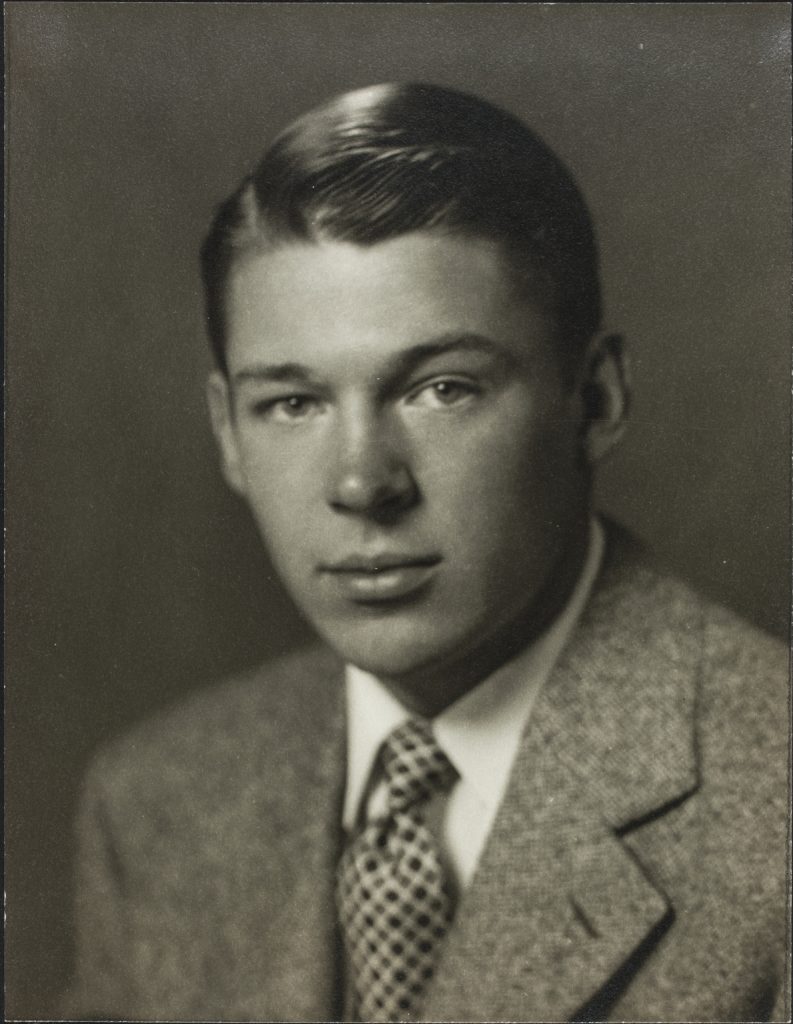

1940

Fall: Enrolls at Stanford University in Palo Alto. Does not challenge his parents’ wishes that he become a doctor or lawyer, but avoids declaring a major. Focuses on taking general education and liberal arts classes for his first three semesters, where he first seriously encounters music, literature, and history, subjects that will fascinate him throughout his life, though he will later comment, “It was mostly the world of writing that opened up— Faulkner, Hemingway, Sherwood Anderson.” 12

1941

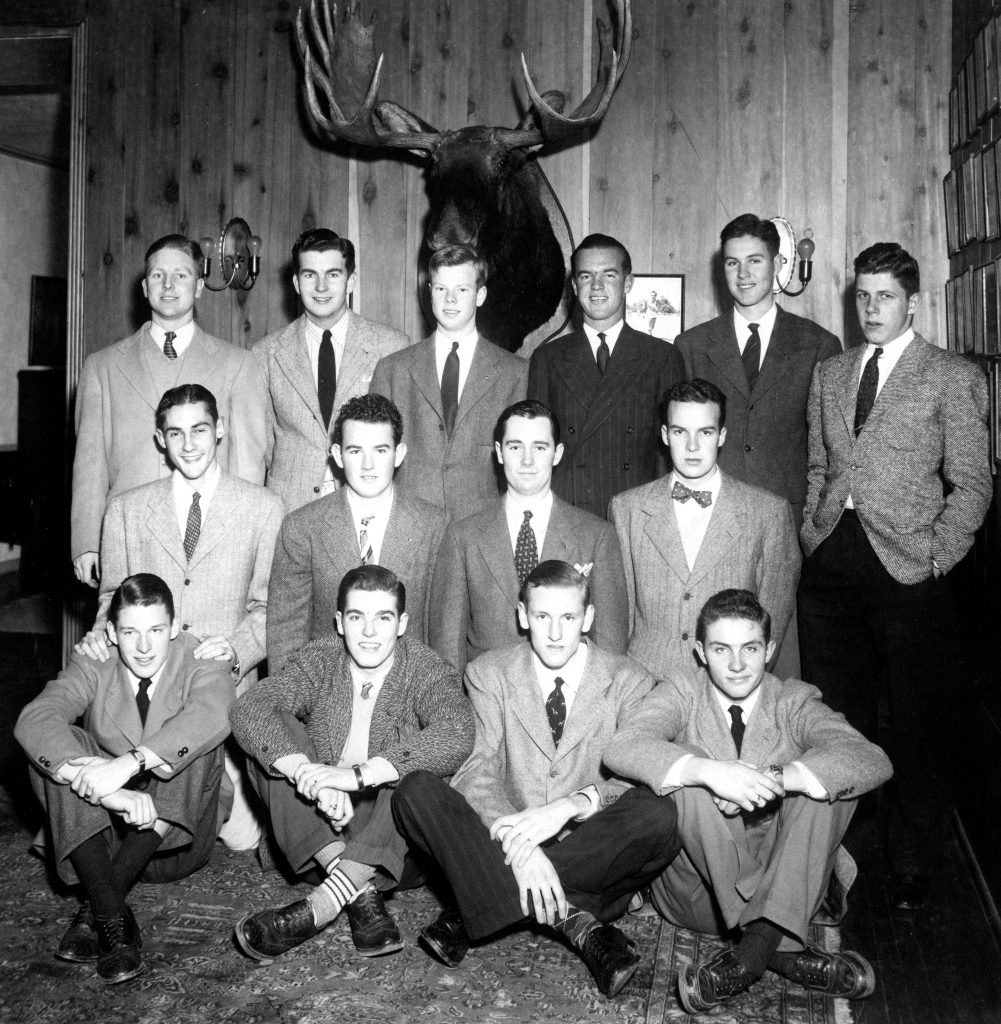

Spring: Joins fraternity Delta Kappa Epsilon (DKE) with childhood friend Richard McDonough. Diebenkorn is known as “Witz,” as he was once mistakenly called Dick “Diebewitz” during roll call. Befriends fellow DKE members Carey Stanton and Donald “Were” Allan. The young men form a tightly knit circle and will remain a part of each other’s lives.

Accidentally falls out of his dorm window one night and becomes a minor celebrity on campus. As Phyllis Diebenkorn recalls,

Well, everybody knew who Dick Diebenkorn was after he fell out the window, cause that was big stuff.

. . . He fell four stories and hit a bush, and broke his nose. But he was very lucky—he could have been dead. And Dorothy [his mother] said that that was what made him into an artist and that he never wanted to be an artist before.13

1942

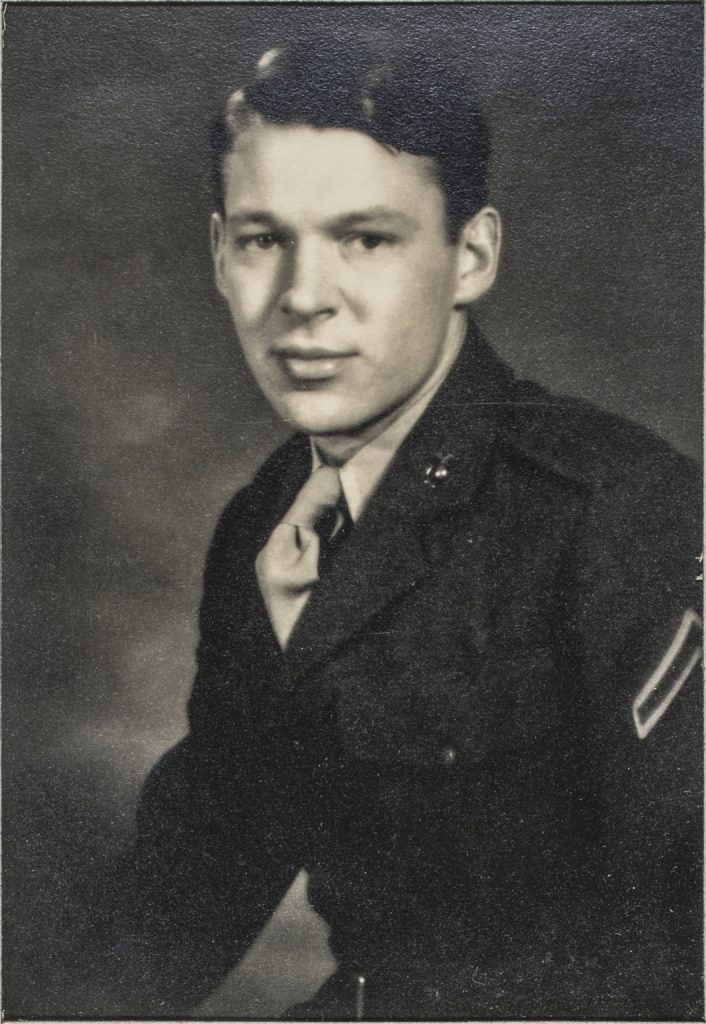

27 March: Three months after Pearl Harbor, Diebenkorn enlists in the U.S. Marine Corps as a private in the reserves; the recruiters promise that he will not be called to active duty until after he graduates. Recommendations for his recruitment cite Diebenkorn as an intelligent and honest young man, displaying the highest moral character.14 Diebenkorn lists Western civilization, biology, math, political science, economics, Spanish, sociology, English, and hygiene as his courses.15

The longest time in my whole life that I didn’t do any artwork, I mean, drawing or painting, was my first two years at Stanford. And my father had sent me there to be a professional lawyer, doctor, something. And so it wasn’t until I enlisted in the military—but still stayed in college—that I began to look around, away from what I had been put in school for, which got to boring me quite a bit.16

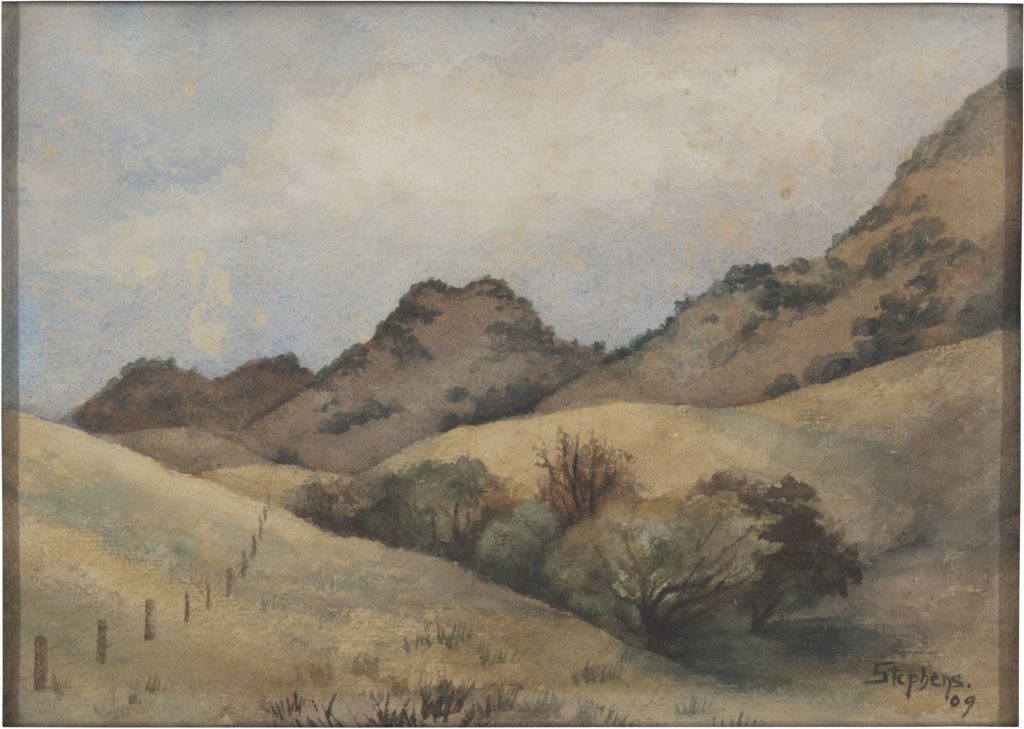

Spring: As American involvement in the war escalates, Diebenkorn begins taking classes in the fine arts. He quickly bonds with Professor Daniel Mendelowitz, taking his classes in watercolor and art history. Mendelowitz, who studied at the Art Students League of New York and was influenced by Reginald Marsh, Charles Sheeler, Arthur Dove, and Winslow Homer, conveys his strong interest in Hopper to his students. Recognizing Diebenkorn’s talent, he allows the young artist to visit the school’s studios as he pleases and to paint outside the classroom, a privilege not afforded to others. Diebenkorn studies oil painting with Russian émigré Victor Mikhail Arnautoff, who teaches “the classical fundamentals of form delineations with an emphasis on precision, discipline and accurate rendering.”17

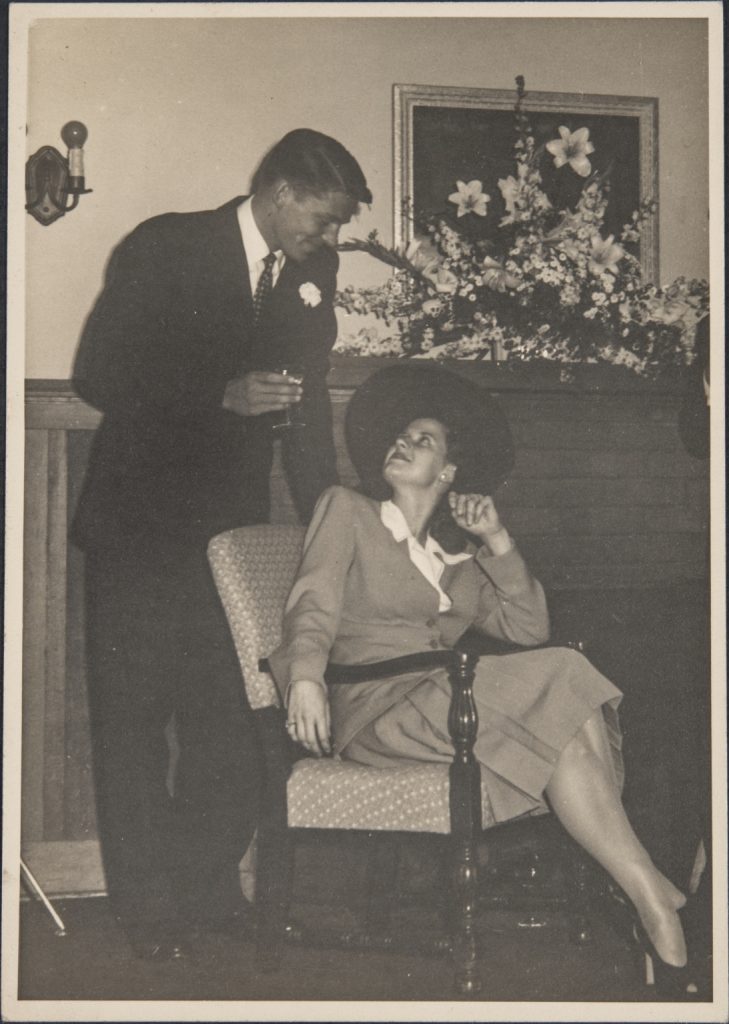

Summer: Meets fellow Stanford student Phyllis Antoinette Gilman. Phyllis, a Kappa Alpha Theta sorority member from Pomona, Calif., is in the class ahead of Diebenkorn. When the two meet, she is taking the course Engineering Drafting and Technical Calculations for Women. Phyllis spends the last quarter of 1942 working for the war effort at Lockheed Martin in Los Angeles.

1944

8 January: Begins Officer Candidate School at Camp Lejeune. According to Phyllis, “mostly he was training to be a Marine officer. He was the top sharpshooter of the whole place. He got some sort of a medal for that.”24

Winter: Phyllis travels east to meet Diebenkorn. As she later recalls,

Dick got out of boot camp and was transferred to Camp Lejeune in North Carolina. So every weekend he was off from Saturday afternoon to Sunday afternoon.

. . . I was going to be a “camp follower.” But I couldn’t find any place for us to live because nobody wanted enlisted men. They wanted officers. . . . Finally, after about two and a half months, a fancy house in New Bern agreed to have us. And she pointed out that all the other people in her house were officers and the only reason they accepted us was that we weren’t damn Yankees. So he was at Camp Lejeune a long time. This was the Winter of ’44.25

12 April: Transfers to Camp Quantico, Virginia, to complete OCS. Phyllis follows, first staying in Arlington and then in a room in nearby Alexandria; eventually Diebenkorn is given permission to live off base with Phyllis.

Aware of the art in the vicinity, makes it a point to visit the museums along the eastern seaboard; collections like these do not exist in California, and their significance is not lost on the young artist. The couple visits the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., numerous times; Diebenkorn absorbs works by Pierre Bonnard, Georges Braque, Paul Cézanne, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, Henri Matisse, Piet Mondrian, Pablo Picasso, Albert Pinkham Ryder, and Charles Sheeler. Matisse’s Studio, quai Saint Michel (1917; see Elderfield essay, fig. 76), Bonnard’s Open Window (1921; see Fine essay, fig. 104), and Ryder’s Moonlit Cove (1880s) are particularly memorable.26 Phyllis recalls,

In Washington we visited the Phillips every weekend. They had concerts . . . and we would sit in there all day. And you could smoke in there, which when I think back is too bad, but at the time we thought it was wonderful because of course we were both smokers. That was the serious beginning of my education. Of course Dick couldn’t wait to get there. . . . It was free. It was a wonderful museum. And there was wonderful music. And there were all those pictures. And pretty much that gallery was our existence.27

They also visit the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., to see the Renaissance and Old Master paintings; the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, where Diebenkorn encounters Jean Arp, Julio González, and Kurt Schwitters; and the A. E. Gallatin Collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where they see Matisse’s Interior at Nice (Room at the Beau Rivage) (1917–18), Klee’s Christmas Picture (1923; see Nordland essay, fig. 19), and Miró’s Dog Barking at the Moon (1926), Painting (Fratellini) (1927), and Object (1932), as well as more Arp collages.28 The couple “feast” on the art; as Diebenkorn will later say, “It wasn’t until Washington that Matisse really hit me hard.” 29

1 July: Fails to qualify for commission and is transferred from OCS one week before graduation.

[During training exercises] I was platoon leader [and was] bringing my platoon through a swamp and . . . somebody sneaked in and tossed a grenade in and presumably blew up the thing, but the position was taken very unspectacularly, and the sergeant was absolutely furious because I didn’t show any Marine Corps spirit. . . . And I just blew up and I told him off!

. . . I should have just stood at attention and said, “Yes, sir.” Maybe it was all a rather complex test, but I fell the other way, and so! I found myself kicked out. . . . Somehow it didn’t bother me very much.30

Phyllis remembers,

[The OCS candidates] were on parade and there was a visiting general observing the troops. It was about ten days before their graduation ceremonies—his new [Lieutenant’s] outfit was all ordered. They were at attention [on the parade ground] because this general was observing them Marching up and down. And he was playing with his rifle, daydreaming, and then he looked down and it was halfway to the ground. And it crashed to the ground with this terrible reverberating sound. And then this general kicked him out. But of course Dick and Dorothy [Diebenkorn’s parents] already had their tickets to come back for the graduation ceremony. They were devastated and humiliated and everything. I guess I was probably a little bit disappointed, but then right away I thought, “Oh my God, he doesn’t have to go!” I don’t think he was invested in [becoming an officer] at all.31

Within six months many of the young men that graduate from Diebenkorn’s OCS Quantico class will have been killed in active duty.

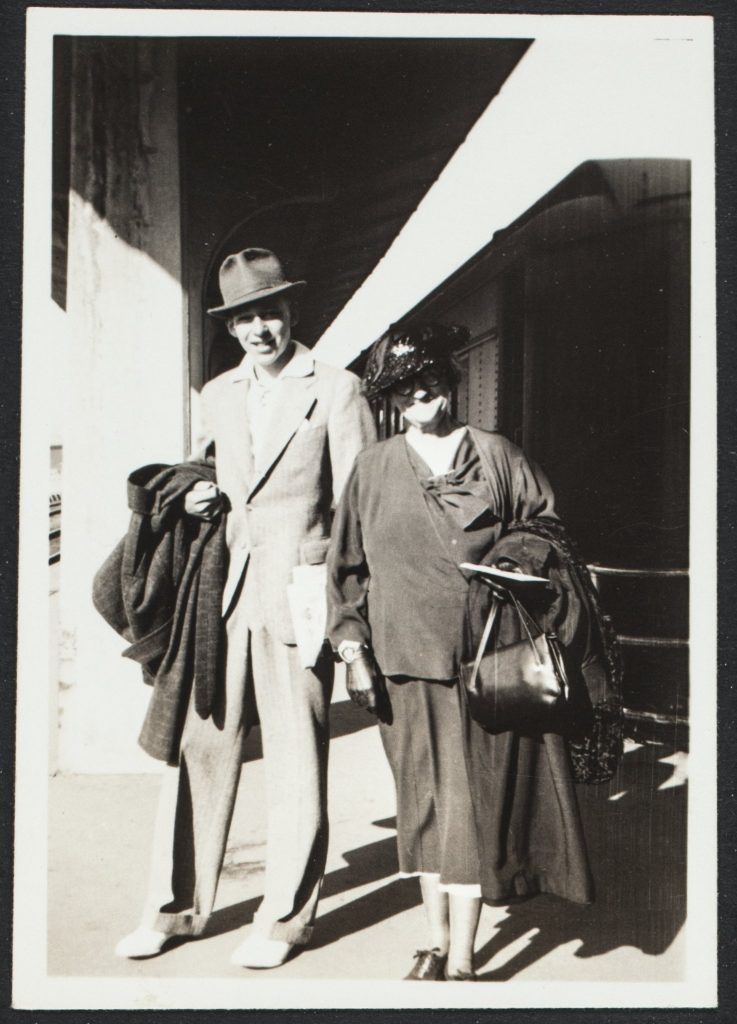

Diebenkorn’s parents visit for the intended graduation; instead the family travels to New York City.

December: Returns to status of private. During the holiday season Diebenkorn draws portraits of his fellow marines and a few officers for their families. A commanding officer notices his talent and transfers Diebenkorn to the photographic department; his principal duty is listed as “artist.”

In the photographic department, Diebenkorn works alongside Disney animators to create animated maps used in training films. The difference between his own abilities and those of the skilled journeymen artists crystallizes; it quickly becomes apparent that Diebenkorn is not of the same ilk. He proves a poor cartographer, unable to obtain an unblemished wash finish, and he dislikes working on directed projects. As his time in the department continues, he is given progressively fewer assignments, and finds himself with free time and access to materials. Diebenkorn’s work from this period is filled with sketches and watercolors of his fellow soldiers, daily life in the barracks, and their surroundings. He begins to experiment with abstraction for the first time.

1945

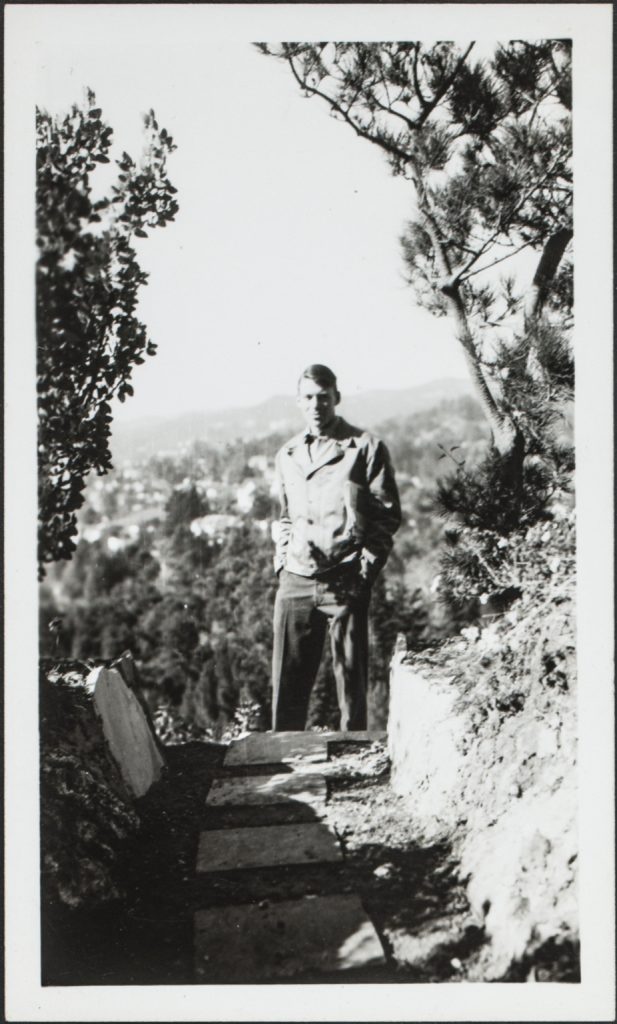

Winter: Transfers to Camp Pendleton, a marine base just outside San Diego, to await overseas deployment to Japan. Traveling by train, he arrives in California on 5 January. Visits parents in Atherton, and goes to the San Francisco Museum of Art (SFMA). At the museum he buys the November 1944 issue of Dyn magazine, published and edited by Wolfgang Paalen, which contains the essay “The Modern Painter’s World” by Robert Motherwell.32

Phyllis moves in with her mother’s sister, Daisy Day, in Los Angeles.

23 May: Daughter, Gretchen, is born. Diebenkorn is given leave to visit his wife and newborn daughter before he ships out to the Pacific theater.

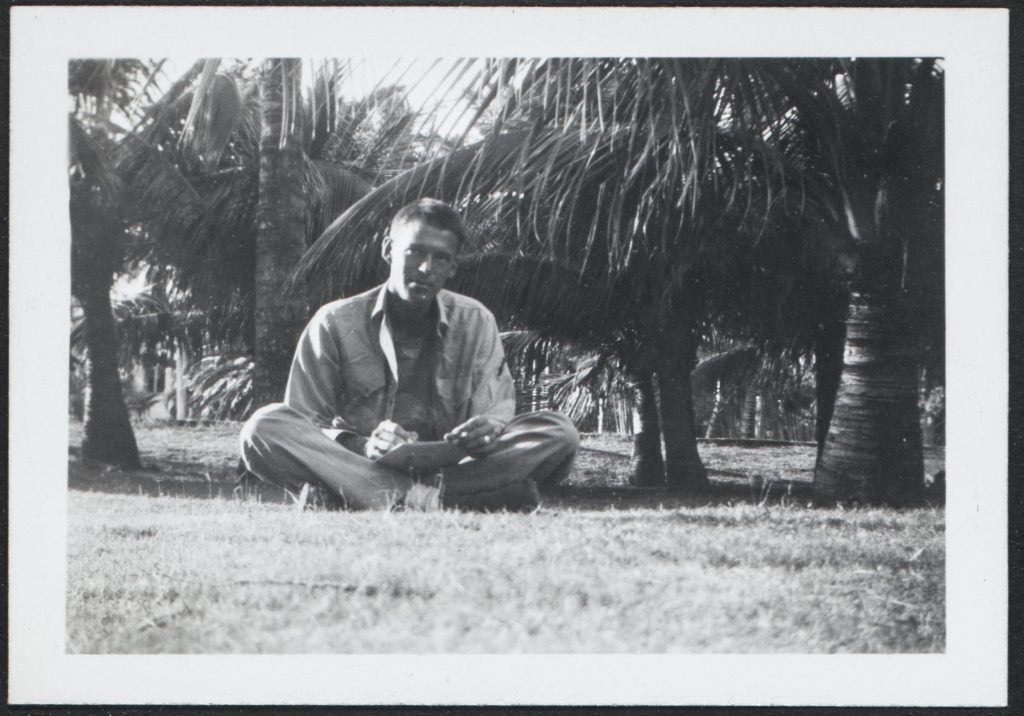

4 June: Embarks on the USS Thetis from San Diego, landing at Pearl Harbor on 11 June. Waits for deployment at the USMC base in Honolulu, Hawaii. Meets friend Bill Davenport at the Honolulu public library.

As a motion picture product tech, Diebenkorn will be dropped in Japanese territory as part of a reconnaissance team including one photographer, one artist, and one writer; the team’s mission is to report back to their commanding officers with detailed descriptions of arms holdings and topographic features. Phyllis recounts,

He was scheduled to be landed behind the lines before the invasion of Japan with a sketchpad and a rifle, and he was supposed to do sketches of where the guns were and where all the stuff was, if he survived at all, what they couldn’t see from the planes. That’s what he was scheduled to do, and it was almost certain death.35

While Diebenkorn’s works become more abstract, he continues to draw the surrounding landscape and sketch his fellow soldiers.

25 September: Returns to Camp Pendleton, having never left the Honolulu USMC base, on the USS Vincennes after the surrender of Japan on 2 September. Phyllis and Gretchen live at Camp Pendleton with Diebenkorn before his honorable discharge from the marines in November as a private.

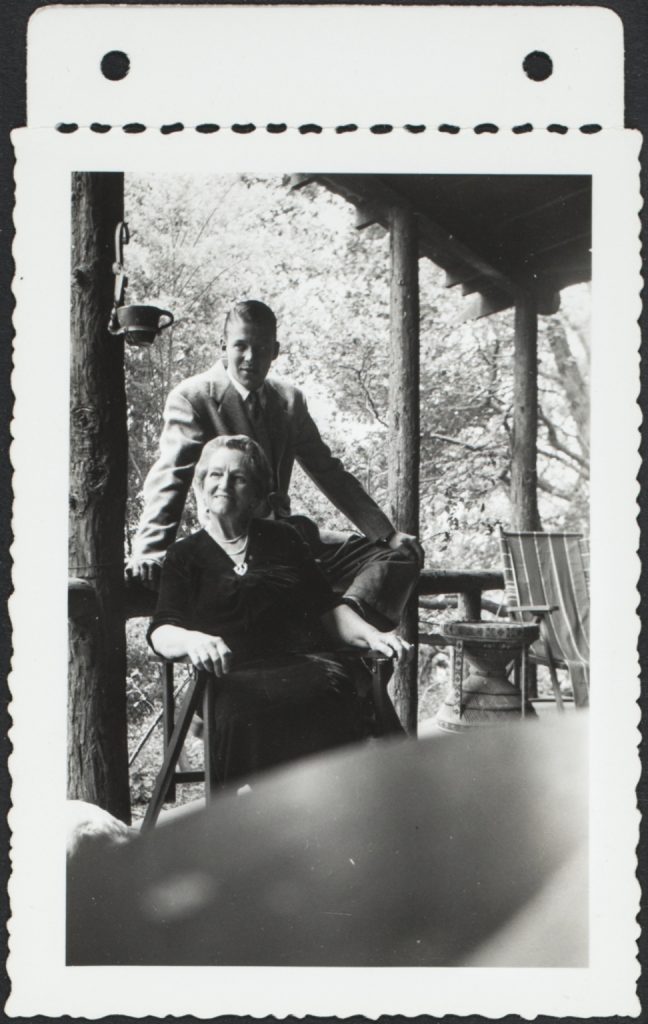

Family moves into Richard Sr. and Dorothy Diebenkorn’s home in Atherton, Calif.

12. Richard Diebenkorn quoted in Maurice Tuchman, “Diebenkorn’s Early Years,” in Richard Diebenkorn: Paintings and Drawings, 1943–1976, exh. cat. (Buffalo: Albright-Knox Art Gallery, 1976), 5.

13. Phyllis Diebenkorn (wife of the artist), interview with Benjamin Grant (grandson of the artist), 2003–4.

14. Letters of recommendation for Richard Diebenkorn’s application to admission as a candidate for a commission in the U.S. Marine Corps, Official Military Personnel File for Richard Diebenkorn, U.S. Marine Corps service number 391556, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), 1942.

15. Ibid., “Application for Appointment to Candidates’ Class for Commission, USMC.”

16. Diebenkorn, interview with Larsen, 1 May 1985.

17. Nordland, Richard Diebenkorn (2001), 12.

18. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.

19. NARA, University of California, Berkeley, transcript.

20. Commonalities exist between Diebenkorn and the artist Robert Motherwell. Born seven years apart, the two both went to Lowell High School in San Francisco, studied with Daniel Mendelowitz at Stanford University, and were brought to visit Sarah Stein’s house in Palo Alto as young art students. On seeing Matisse for the first time at the Steins’, Motherwell said, “It went through my heart like a golden arrow and I had one real intuition immediately. I thought, this is what I want to belong to.” Robert Motherwell, interview with Martin Friedman and Dean Swanson, 1 Aug. 1972, quoted in Tim Clifford, “Chronology,” in Robert Motherwell Paintings and Collages: A Catalogue Raisonné, 1941– 1991, by Jack Flam, Katy Rogers, and Tim Clifford (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 181. Later, the Diebenkorns became very close friends with Motherwell’s stepsister, Ann Rosener. Their meeting was not related to their knowing the older artist.

22. For more information on Hofmann’s time in California, please refer to chapter 3 of Tina Dickey, Color Creates Light: Studies with Hans Hofmann (Canada: Trillistar, 2011).

23. Diebenkorn, interview with Larsen, 1 May 1985.

24. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.

25. Ibid.

26. Phyllis Diebenkorn noted that “Dick was very involved with one big Ryder, which was densely painted and mostly all cracked up, but wonderful.” Ibid.

27. Ibid. In his interview with Susan Larsen, Diebenkorn said, “[We] just feasted—on the National Gallery and Phillips Memorial Gallery and Corcoran.” 1 May 1985.

28. Tuchman, “Diebenkorn’s Early Years,” 6–7; John Elderfield, The Drawings of Richard Diebenkorn, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1988), 31.

29. Diebenkorn, interview with Larsen, 1 May 1985.

30. Ibid.

31. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.

32. Diebenkorn with Butterfield, Pentimenti, n.p.

35. Phyllis Diebenkorn, interview with Grant.