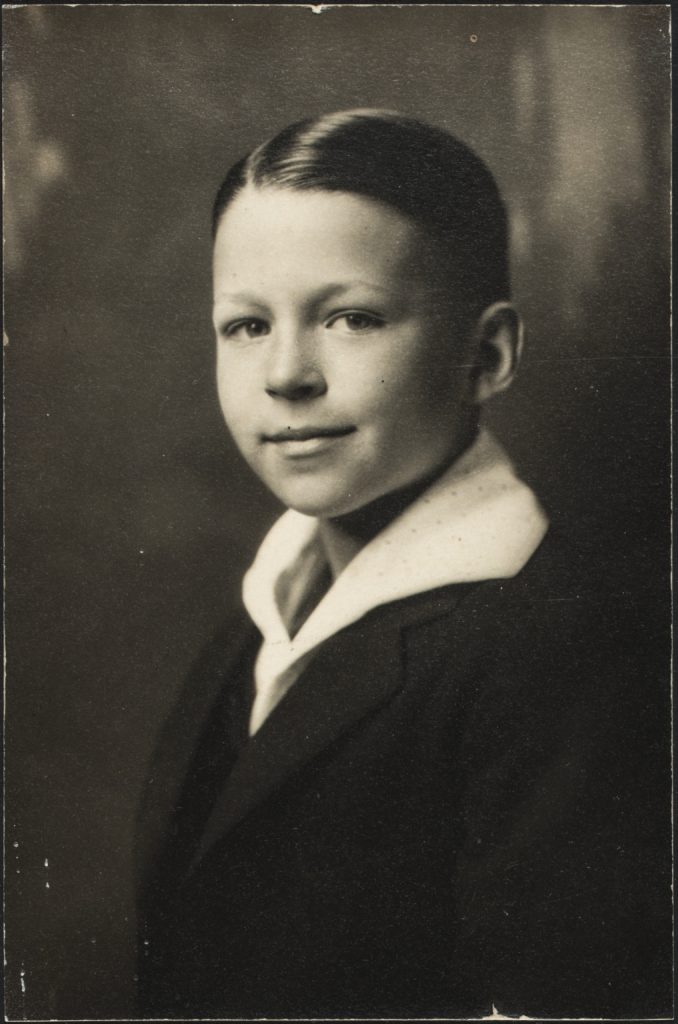

1922

22 April 1922: Richard Clifford Diebenkorn Jr. is born to Richard Clifford Diebenkorn Sr. and Dorothy née Stephens in Portland, Oregon.1 Diebenkorn Sr. is a career employee for the Dohrmann Hotel Supply Company, first as a salesman and designer and later as vice president, retiring after fifty years of service. A colleague will later describe him as a “‘straight-arrow’—highly principled, reserved, never spoke personally or about his family. Strictly business.”2

My mother was a Californian. She was born in San Diego. And my father came here [to San Francisco] from Cincinnati in nineteen-o-something-or-other. His business moved him to Portland briefly to start a new office. . . . And he got the office going in Portland, and it took years, I think, and then they moved back to California, back to San Francisco.3

c. 1925

The family returns to California, settling at 245 Moncado Way in San Francisco’s St. Francis Wood/Ingleside Terraces neighborhood. Diebenkorn attends the Commodore Sloat Grammar School and Aptos Junior High. An only child with busy parents, he spends most of his free time drawing.

My father, who was . . . very upper bourgeois, liked art but wanted me to be a professional man. It was our cook [Effie] who gave me art materials—and my parents liked that, in the early years, because it kept me out of their hair. With these materials I drew adventure pictures, with lots of arrows flying, and mayhem. But the person who really encouraged me a lot was my grandmother, my mother’s mother—Florence McCarthy Stephens was her name. She was one of these all around women who are so admired today. She was a painter and a poet and a lawyer and had a radio program in San Francisco, reviewing books. During the First World War, she defended German-Americans who had their windows broken, and so forth, though she herself was Irish. It affronted her sense of justice. She appreciated my interest in Romantic literature— she read to me, and gave me a collection of books at just the right time for me to enjoy them. She read me Malory’s “Le Morte d’Arthur” and made it understandable.4

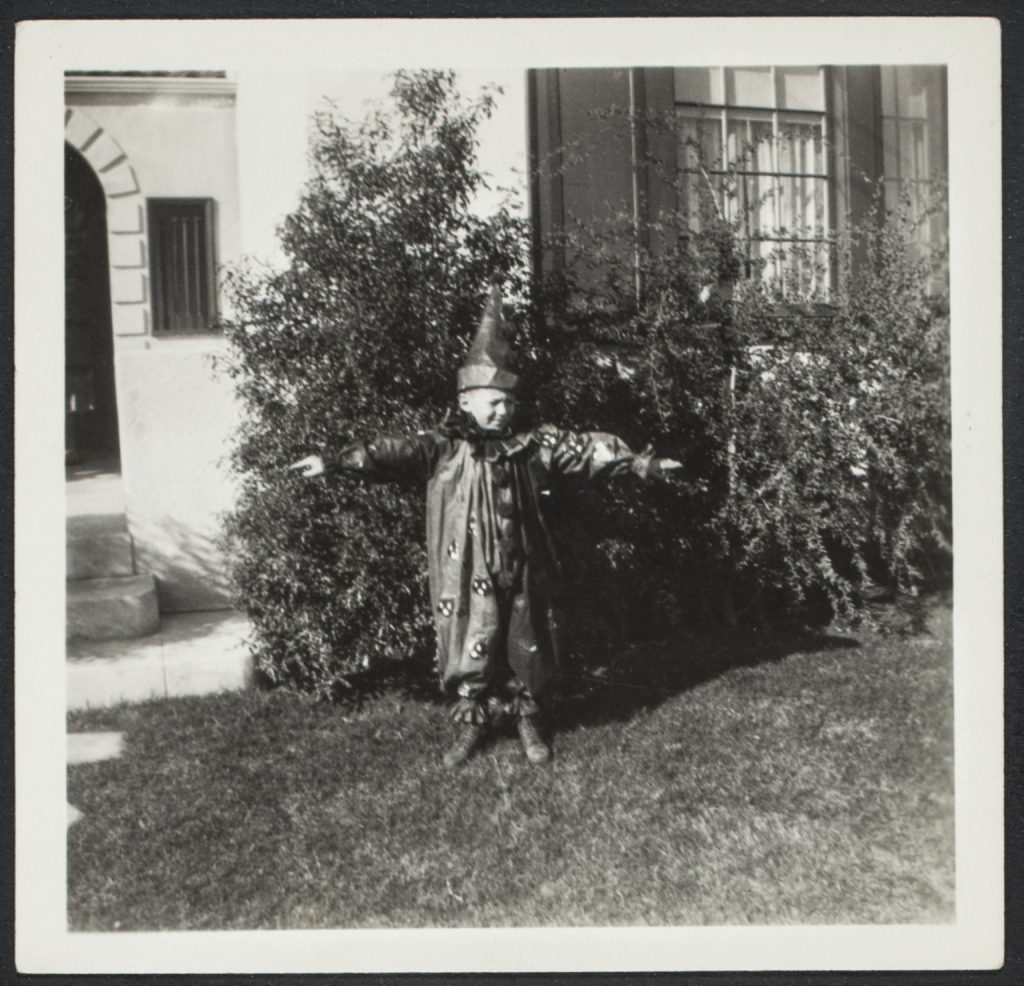

Spends Summers at Florence Stephens’s home in Woodside, Calif., near Palo Alto. She encourages his imagination, and he develops a rich fantasy life, carving swords and shields emblazoned with insignia and heraldry.5

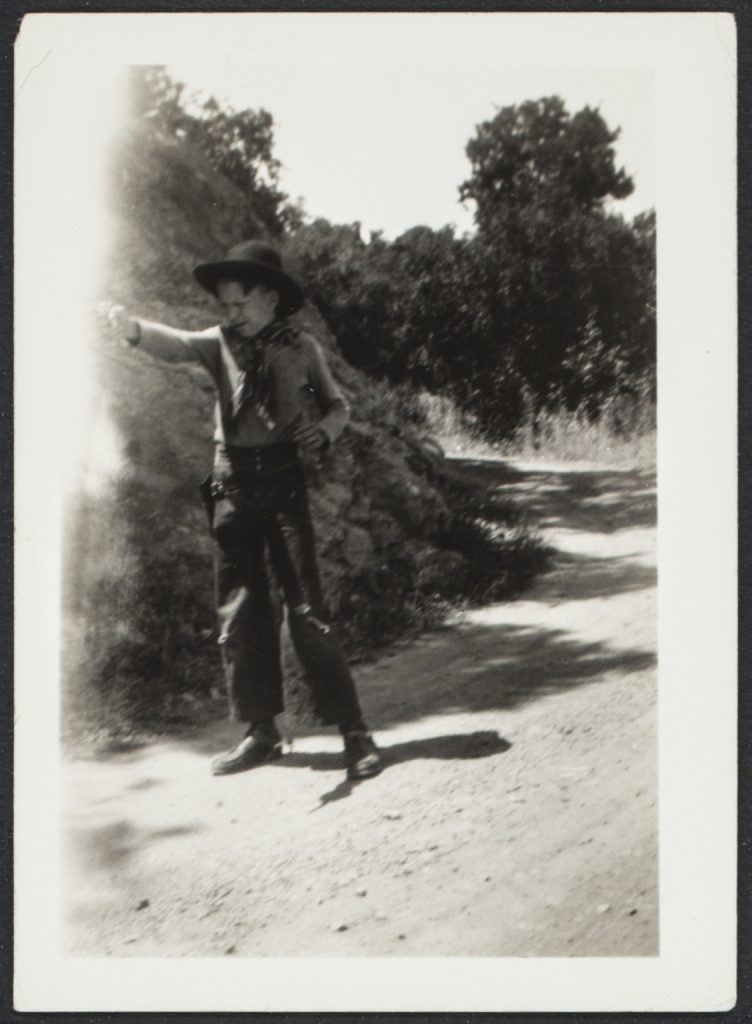

The books and images that surround Diebenkorn as a child—many of them gifts from his grandmother—become enduring visual and intellectual references. These include a set of postcards featuring the Bayeux Tapestry; N. C. Wyeth’s illustrations for Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped, Treasure Island, and Black Arrow; Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates and his illustrations for a series of Arthurian legends; depictions of the world of the Wild West by Frederic Remington, Charles Russell, and Will James; the adventure stories of Alexandre Dumas and Rafael Sabatini; and especially the Oz books by L. Frank Baum with illustrations by W. W. Denslow.6 The artist’s early drawings reflect the subjects and compositions of his books and their illustrations, like naval battle scenes and marooned sailors, locomotives speeding through the prairies, jousting knights, and cowboys and Indians sparring in saloons; at times his sketches would carry a striking verisimilitude to their sources.

In the classroom . . . I used strong color, painted loosely, took subjects that the other fellows were interested in. . . . At home my work was quite different. It was a sort of elaborate note-taking with reference to my private world. The pictures were tight, rather small, the color was used to identify things the picture being a means of my being transported and brought into real contact with things of importance to me. . . . What I do now combines these approaches.7

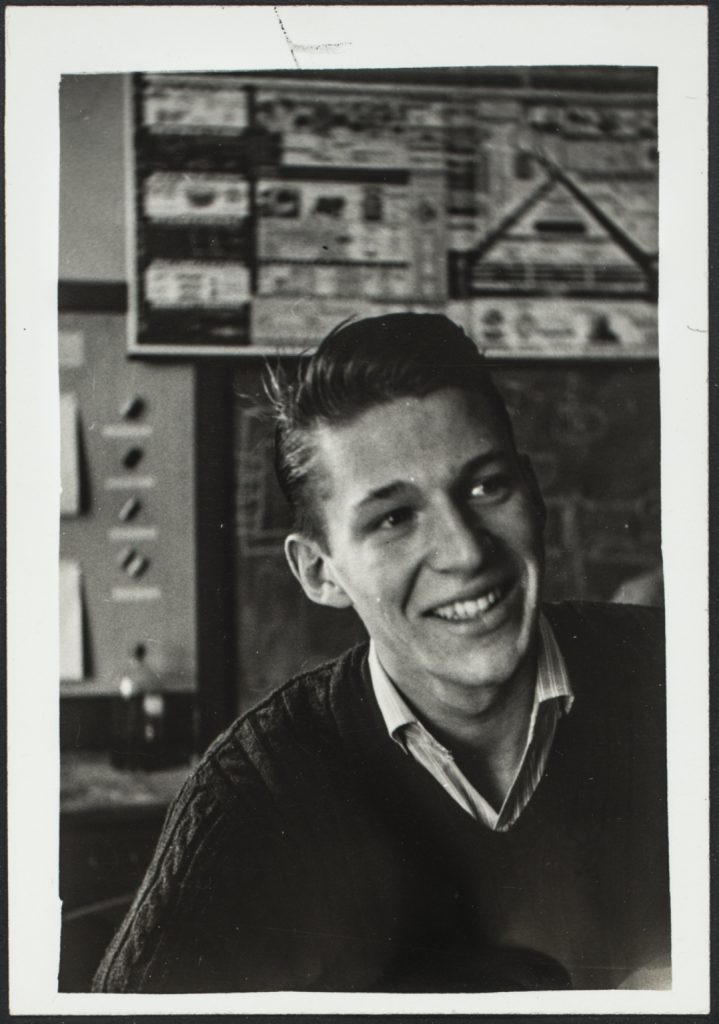

1936

Visits the Vincent van Gogh retrospective at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor with his grandmother.8

1937

Attends Lowell High School, then located on Masonic and Hayes near Golden Gate Park, in San Francisco. Through a subscription to Esquire magazine, becomes aware of New York artists Robert Henri and William James Glackens of the Ashcan School, among others. Comes across the paintings of Edward Hopper in a book received as a Christmas gift. After reading W. Somerset Maugham’s The Moon and Sixpence, researches Paul Gauguin—upon whom the book is presumed to be based—in the library, and as a result also encounters the works of Paul Cézanne.9

I think we take for granted . . . the Expressionist kind of distortion. This is something we assume now, and I think that [until] recently . . . one did not exaggerate or distort. And in line with that, I recall seeing Cézanne for the first time shortly before I went to college. The crazy sort of spareness and the distortions just hit me very hard. There were tabletops where I felt apples should roll off. And buildings with skewed verticals and horizontals and backgrounds. . . . A horizon-line or floor-line, which came in from one side at this level and popped out at a different level, and . . . [it was] very disquieting, shocking, for me. Because my discipline, as a teenager, had been strictly drawing as craft in terms of accurate rendition of what’s out there.10

Parents consider their son’s interest in art to be a passing phase.

And it was assumed all along in my teenage years that I’d be going to Stanford, but of course I was going for a serious reason; I wasn’t going there to become an artist. . . . And I can remember my father telling me at some point, about the time he started getting nervous, when I was getting older and older and still wanting to be an artist. . . . “You know, this drawing and painting thing is just a fine avocation, and I think you’re in an enviable position to have some, to have this to do in your life as well as what you really do with your life.” 11

Florence takes Diebenkorn on a train trip through the Southwest to Mexico.

1. Diebenkorn’s middle name was originally Clarence, after an uncle who died during the 1918 influenza epidemic. However, Diebenkorn wanted to be a “real junior,” and at a young age changed his middle name to Clifford, to match his father’s.

2. For a more in-depth discussion of Diebenkorn’s parents and their heritage, see Gerald Nordland, Richard Diebenkorn, 2nd ed. (New York: Rizzoli, 2001), 262n1.

3. 1 May 1985, oral history interview with Richard Diebenkorn, 1 May 1985–15 Dec. 1987, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview conducted by Susan Larsen.

4. Richard Diebenkorn quoted in Dan Hofstadter, “Almost Free of the Mirror,” New Yorker, 7 Sept. 1987, 61.

5. Diebenkorn, interview with Larsen, 1 May 1985.

6. Gretchen Diebenkorn Grant, in conversation with the author, 17 Jan. 2013, recalled that these illustrations and stories, especially the Oz books by L. Frank Baum and W. W. Denslow, fascinated the young artist as tales of transformation. He was drawn to stories that elaborate on the nuances in the interstice between fantasy and reality. While the difference between the two is critical, so is the acknowledgment that the elements that make up fantasy can also be found in our own quotidian world.

7. Richard Diebenkorn to Joseph Pulitzer Jr., 8 Jan. 1957, quoted in Charles Scott Chetham, Modern Painting, Drawing and Sculpture: Collected by Louise and Joseph Pulitzer, Jr., exh. cat. (Cambridge, Mass.: Fogg Art Museum, 1957), 31.

8. Diebenkorn, interview with Larsen, 1 May 1985. See interview for a more in-depth discussion of this visit.

9. For further information on the artwork Diebenkorn was exposed to in high school, see Nordland, Richard Diebenkorn (2001), 10. “Eight or ten articles [of Esquire magazine] a year were published on individual artists then working in New York, among them important leaders of the Ash Can School—Robert Henri and William Glackens—as well as distinguished artists in midcareer such as Bernard Karfiol, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, William Gropper, Henry Varnum Poor, Abraham Rattner, Raphael Soyer, and others less well known. However, no difficult modern artists, and no [Arthur] Dove or [Georgia] O’Keeffe, Morgan Russell, or MacDonald Wright were presented.”

10. Diebenkorn, interview with Larsen, 1 May 1985.

11. Ibid.